This essay is part of Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, a compilation of 21 essays presenting innovative, evidence-based, and concrete ideas to shape the 2020 policy debate. The authors in the new book include preeminent economists, political scientists, and sociologists who use cutting-edge research methods to answer some of the thorniest economic questions facing policymakers today.

To read more about the Vision 2020 book and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

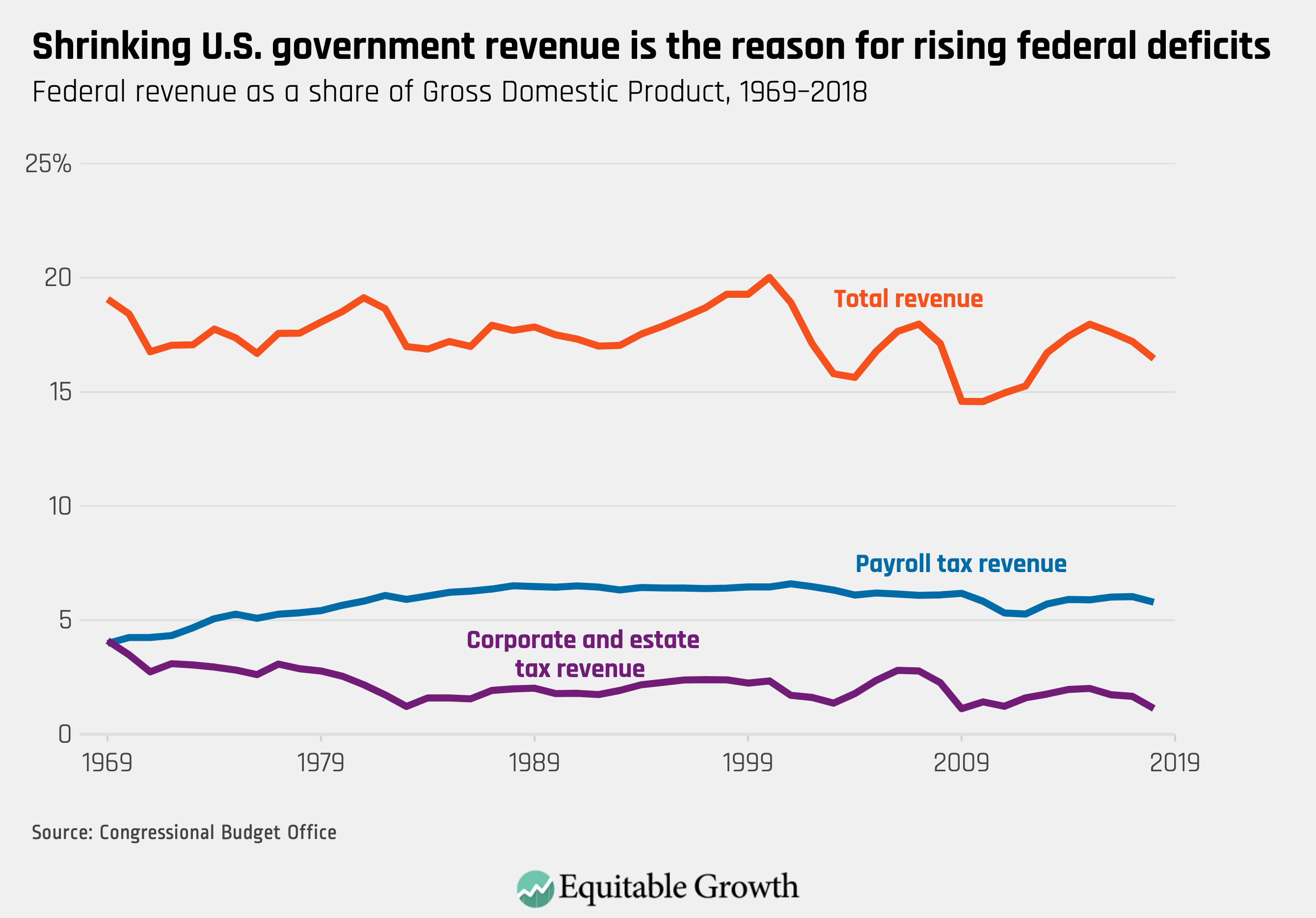

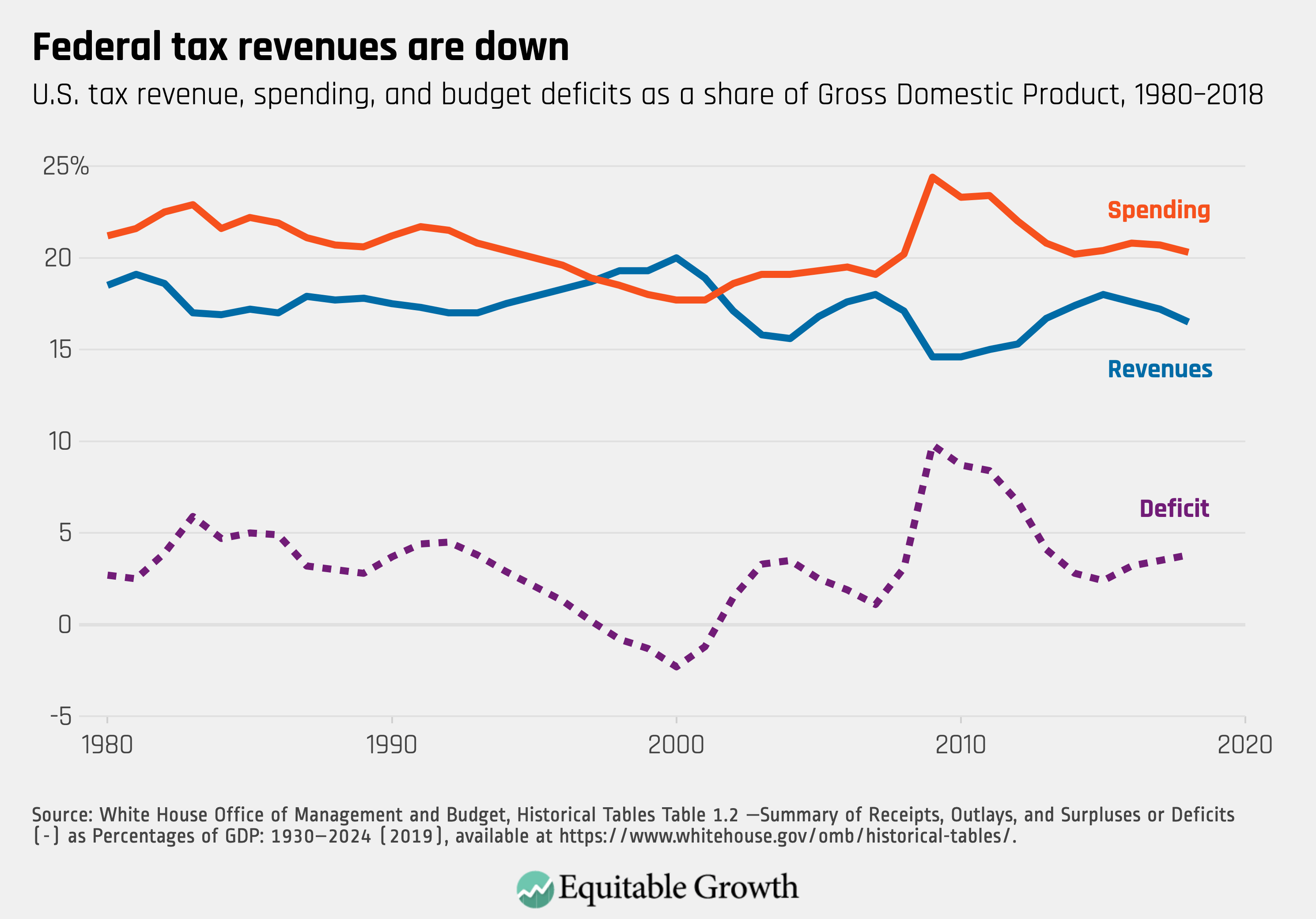

The fiscal position of the United States was much healthier in the late 1990s than it is today. The federal government now collects 3 percent less of Gross Domestic Product than it did two decades ago, yet the nation faces a number of pressing needs for new spending, including on infrastructure, research and development, education, and healthcare. This essay draws on new research to present a modest proposal to address this problem: roll back federal tax policy to 1997.

We propose a set of reforms to the individual income tax and estate tax, with particular attention to the tax treatment of “pass-through” income—profits from certain types of businesses that, for tax purposes, pass through to individual owners who then pay income tax on those profits. These reforms would raise revenues by $5 trillion over the next decade and reduce after-tax income inequality.

In terms of tax revenues, it’s important to recognize that pass-through firms generate more taxable income than traditional C corporations, so the tax treatment of these business entities and their owners is key. Higher tax rates on individual income and these reforms for pass-through taxation represent important steps for taxing substantial amounts of income.

Top incomes and U.S. tax policy

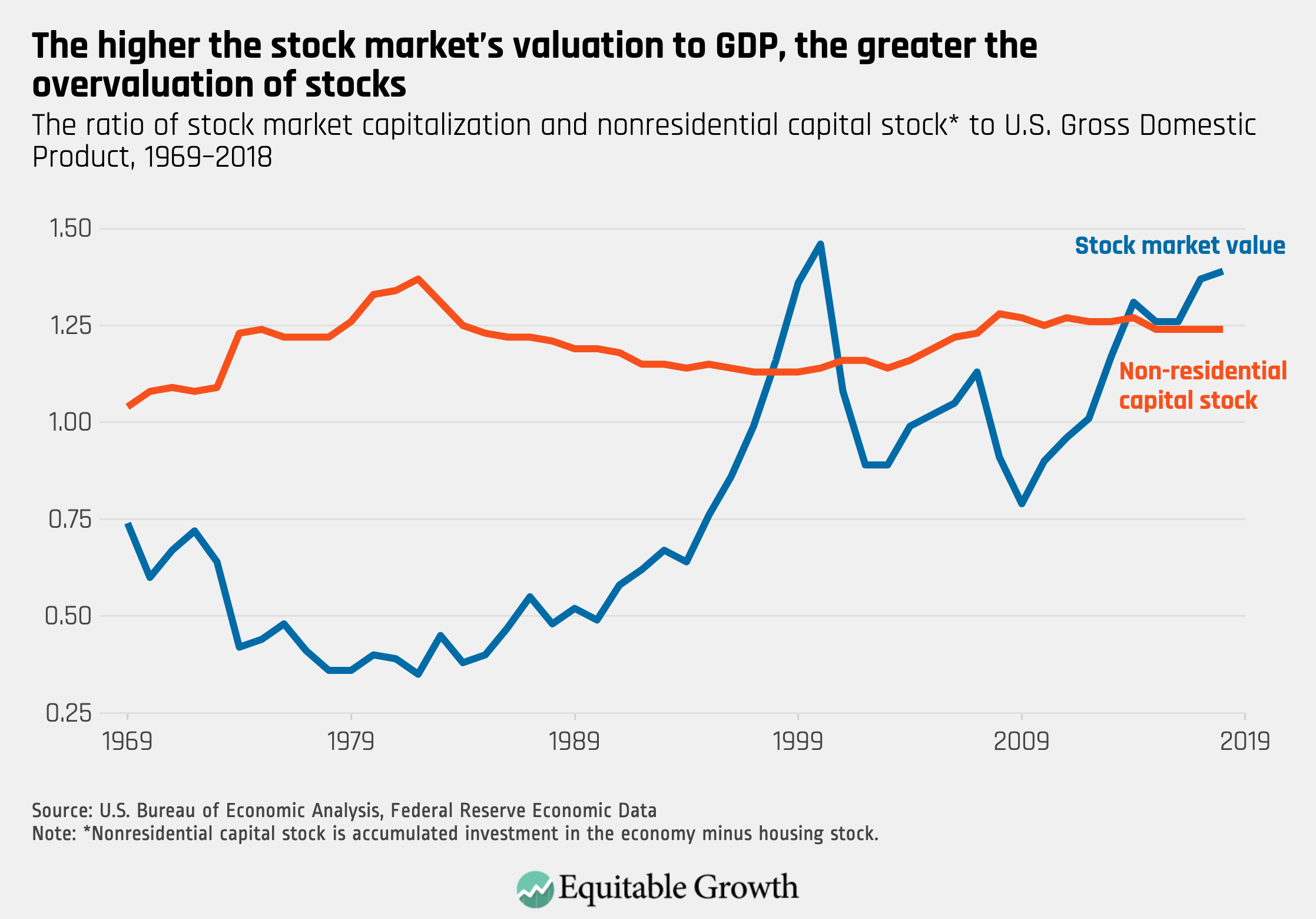

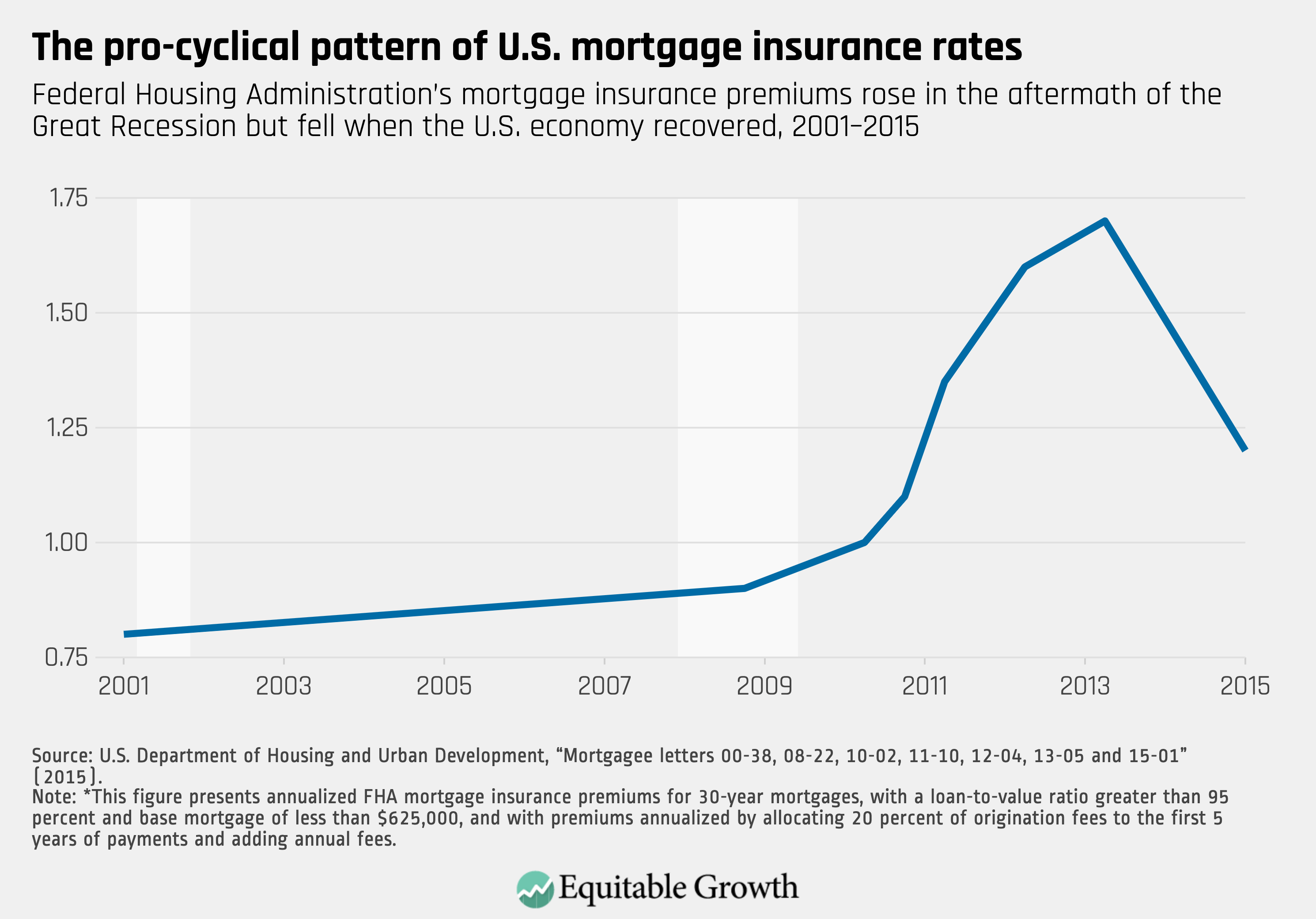

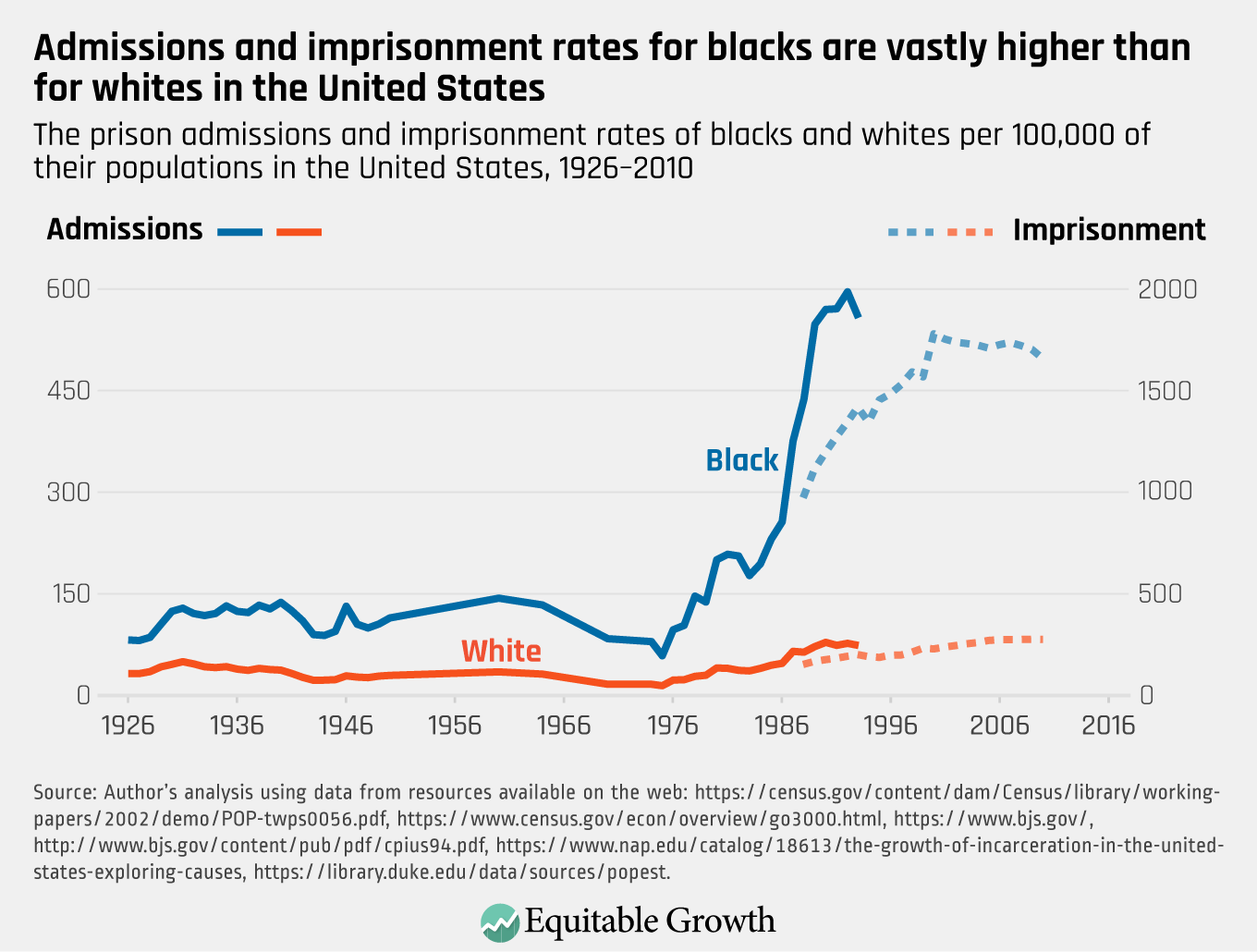

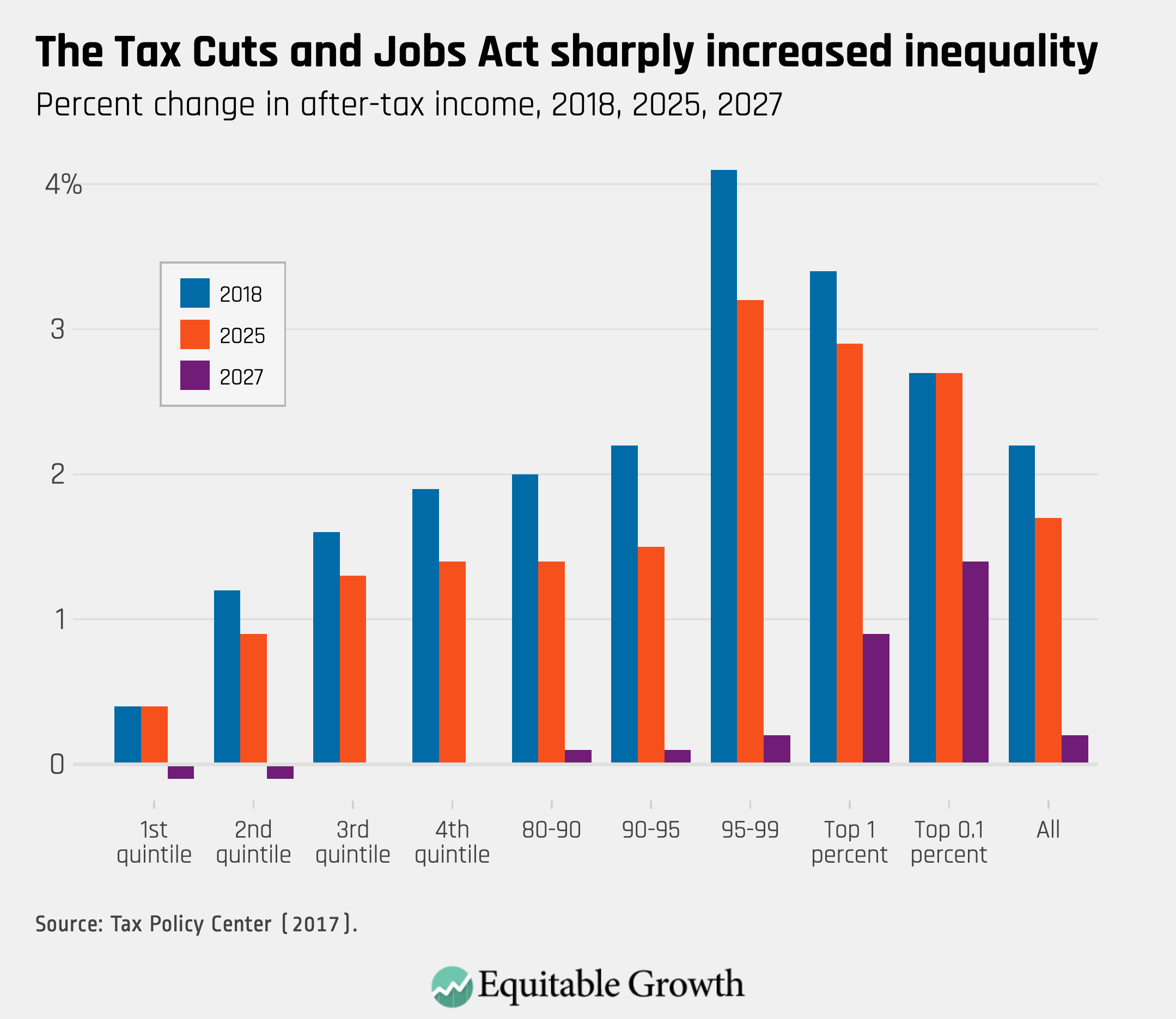

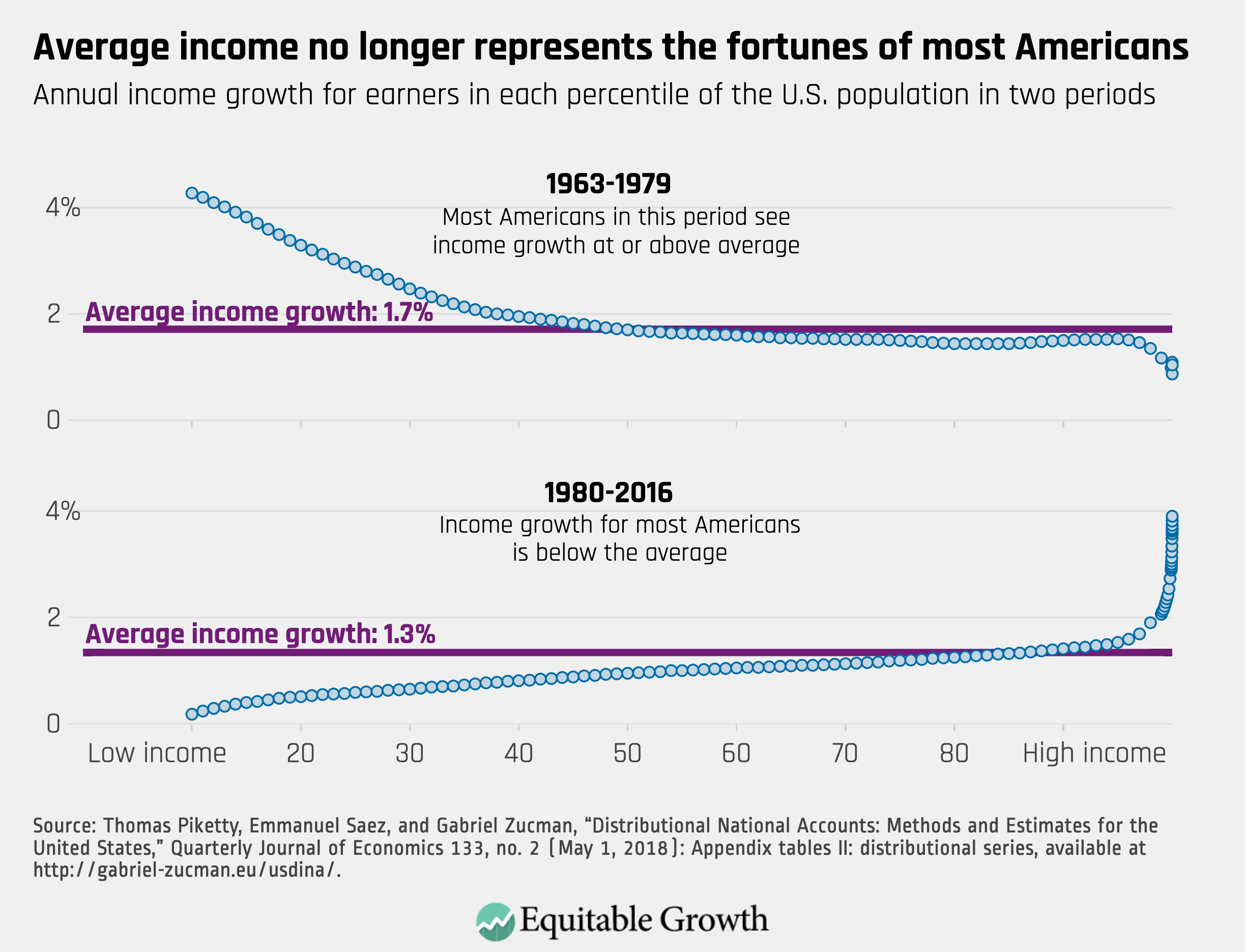

The rise in income inequality over the past several decades presents a natural place for federal policymakers to start to raise revenue. The rise of top incomes since the mid-1990s coincided with a series of changes to tax policy that reduced top tax burdens and contributed to rising federal budget deficits. These revenue reductions include the 2001 income tax cuts, the 2003 dividend tax cut, the 2001 estate tax cuts, and the reduction in capital gains taxes in 1997 and again in the early 2000s.

More recently, changes include the permanent extension of part of the 2001 income tax cuts and the personal and business income cuts in the 2017 tax law. While there were modest increases in income taxes in 2013, the net effect over the past 25 years of federal income tax policy has been to reduce the overall revenue collected from top earners. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

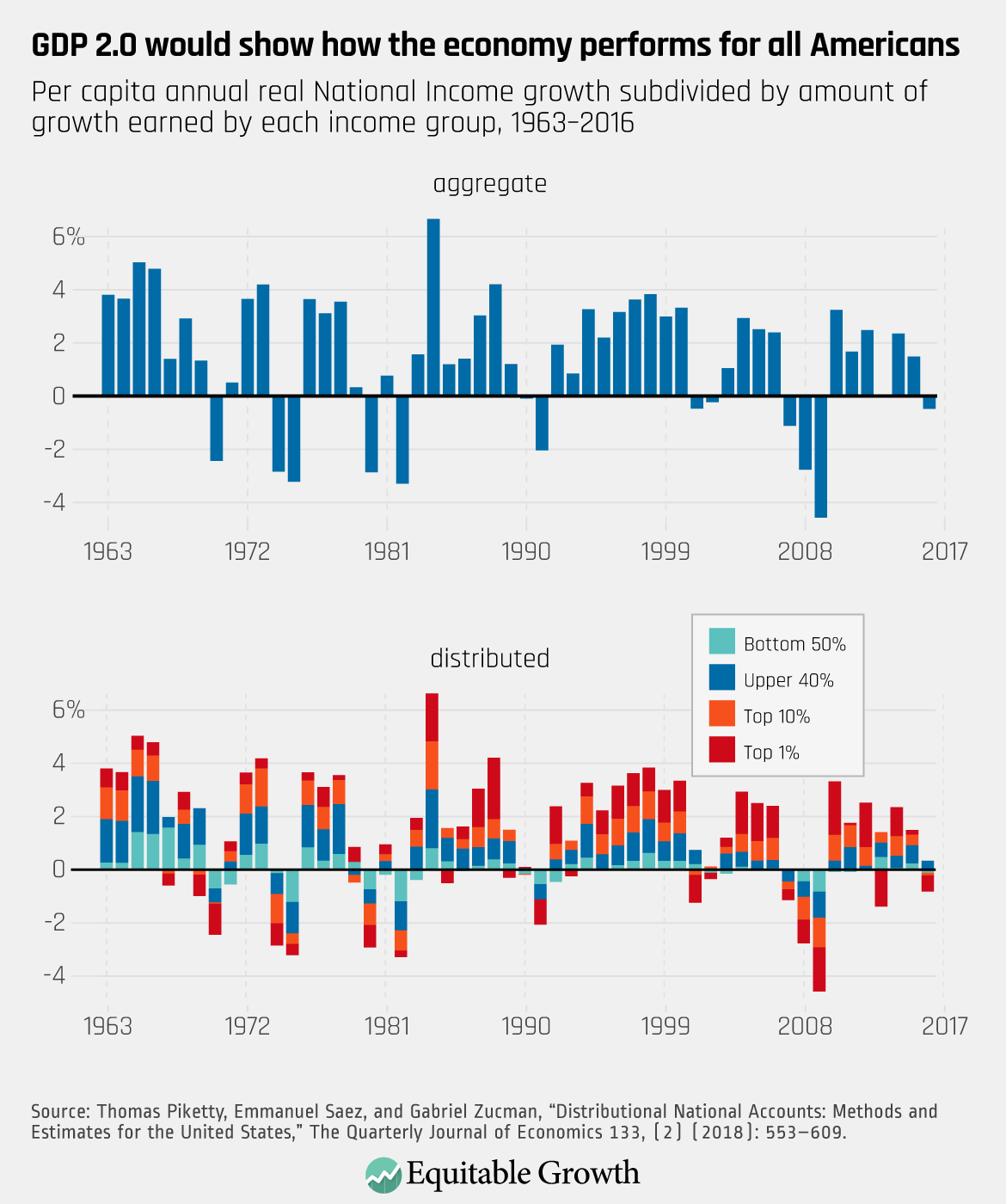

Our research seeks to characterize the nature of top income inequality and understand the drivers of its recent rise. Within the base of taxable income, nearly half of the rise since 1980 in the top 1 percent of income share comes from pass-through businesses, which includes the ordinary income earned by partners in partnerships and the profits of S corporation owners.1 While this income is taxed as business profits, its underlying nature more closely reflects the labor income of the business owners.2

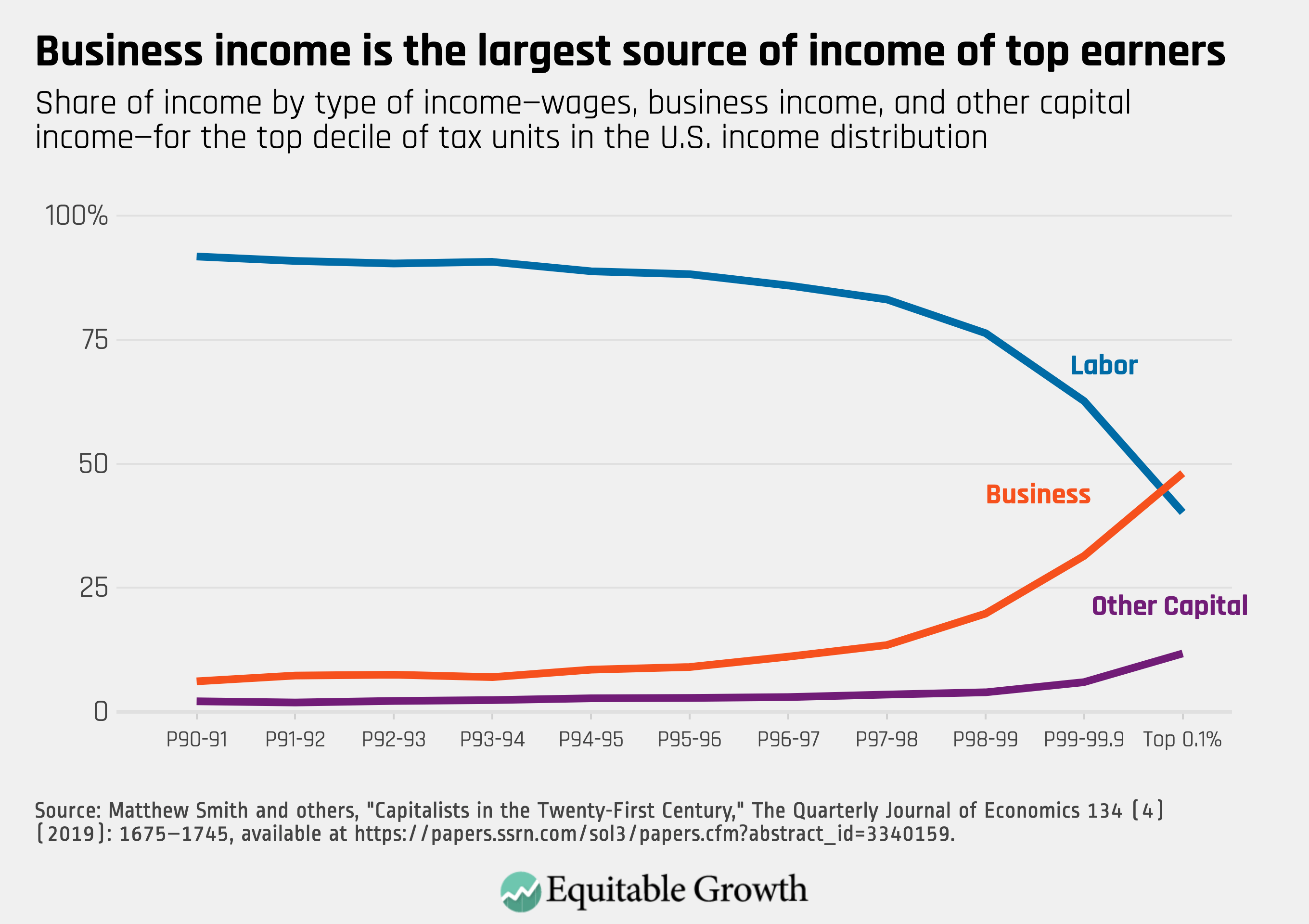

We highlight three implications of these findings. First, policymakers need to look at income beyond wage income to understand top incomes and how to tax them. More than sixty cents of every dollar of income for top earners comes from nonwage sources. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

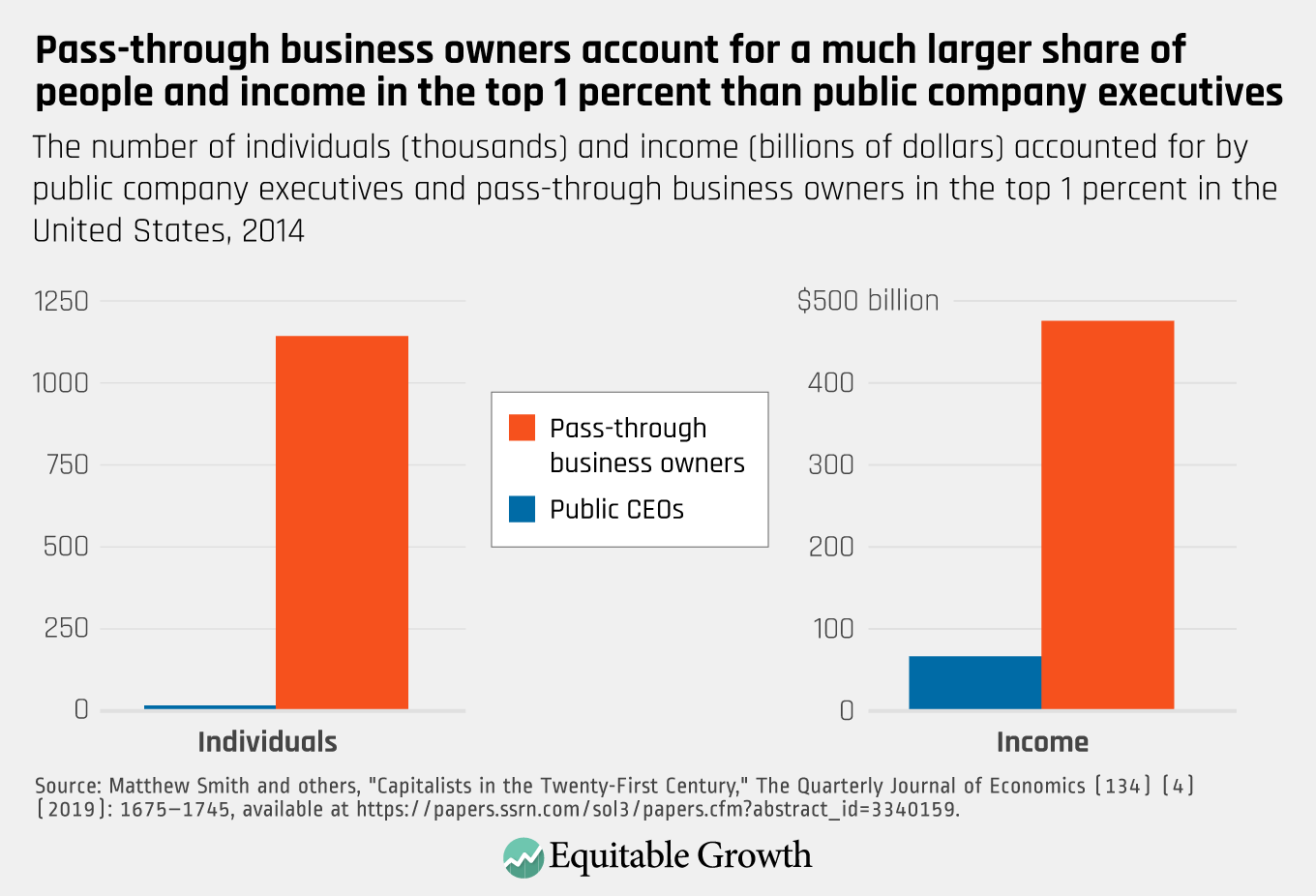

Second, the data reveal a striking world of business owners who prevail at the top of the income distribution. Most top earners are pass-through business owners—a group that encompasses consultants, lawyers, doctors, and owners of large nonpublicly traded businesses such as autodealers and beverage distributors. More than 69 percent of the top 1 percent of income earners and more than 84 percent of the top 0.1 percent of income earners accrued some pass-through business income in 2014, the most recent year for which complete data are available.3

In 2014, in absolute terms, that amounts to more than 1.1 million pass-through owners with annual incomes of more than $390,000, and 140,000 pass-through owners with annual incomes of more than $1.6 million. In both number and aggregate income, these groups far surpass that of top public company executives, who have been the focus of much inequality commentary. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Third, policymakers need to take seriously the nebulous boundary between labor and capital income, especially among business owners who can flexibly characterize their income to minimize taxes. Politicians in both parties, for example, have successfully lowered their taxes through the so-called Gingrich-Edwards loophole, named after former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich (R-GA) and former Sen. John Edwards (D-NC), which involves characterizing compensation for consulting and speaking fees as business profits rather than wages.

Our tax reform proposal

The growth of pass-through businesses in recent decades and the concentration of ownership make the taxation of pass-throughs a central element of reform. While we believe that reforming the broader corporate tax system is important, detailing reforms to the corporate tax system is beyond the scope of this proposal. In terms of tax revenues, however, it’s important to recognize that pass-through firms generate more taxable income than traditional C corporations.4

The tax treatment of these pass-through business entities and their owners is a critical part of reform. Higher tax rates on individual income and these reforms for pass-through taxation represent important steps for taxing substantial amounts of income. Rolling back tax policy to 1997 entails reforms in four main areas: marginal income tax rates, business income taxes, taxes on dividends and capital gains, and estate taxes. Let’s consider each one in turn.

Marginal income tax rates

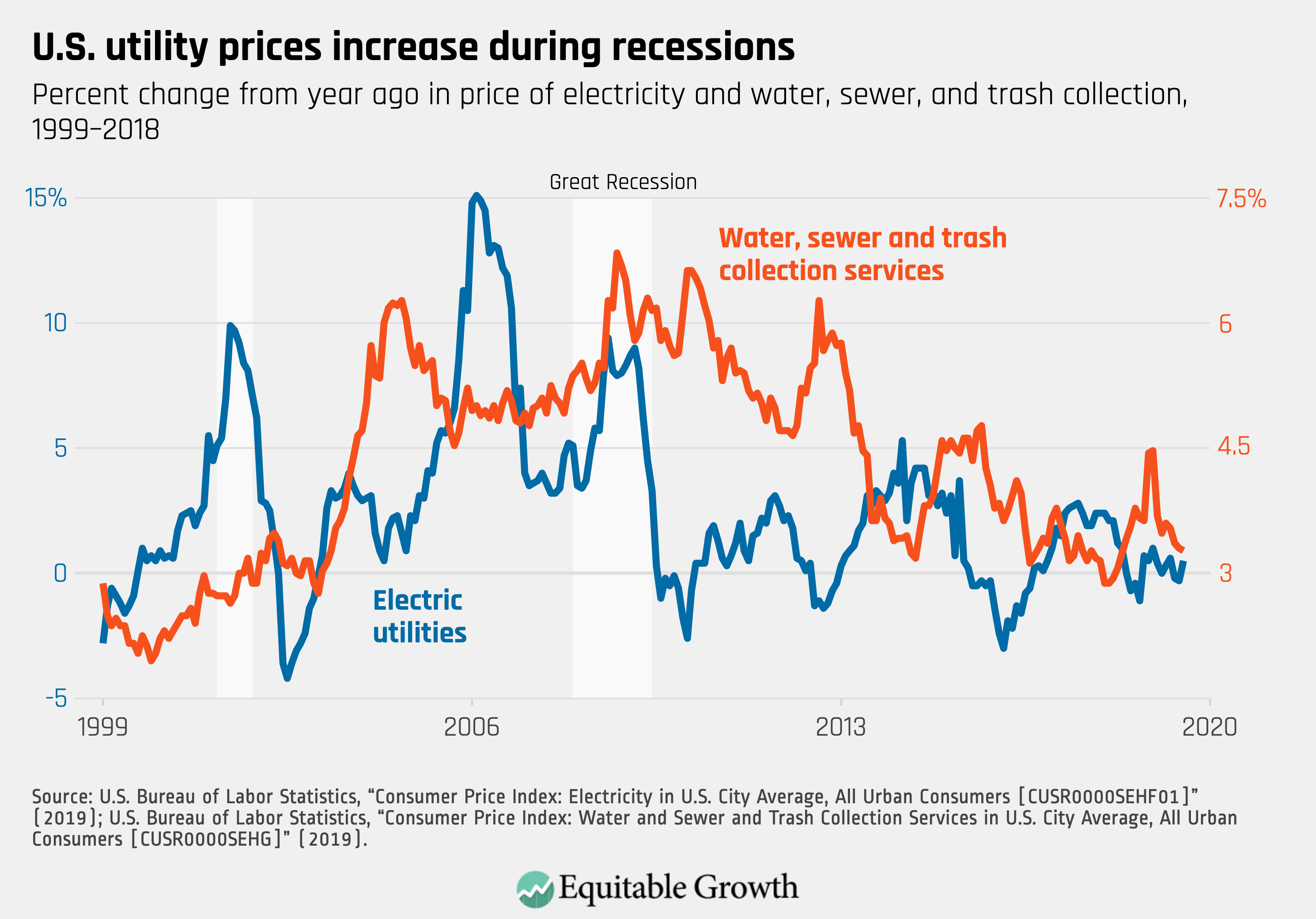

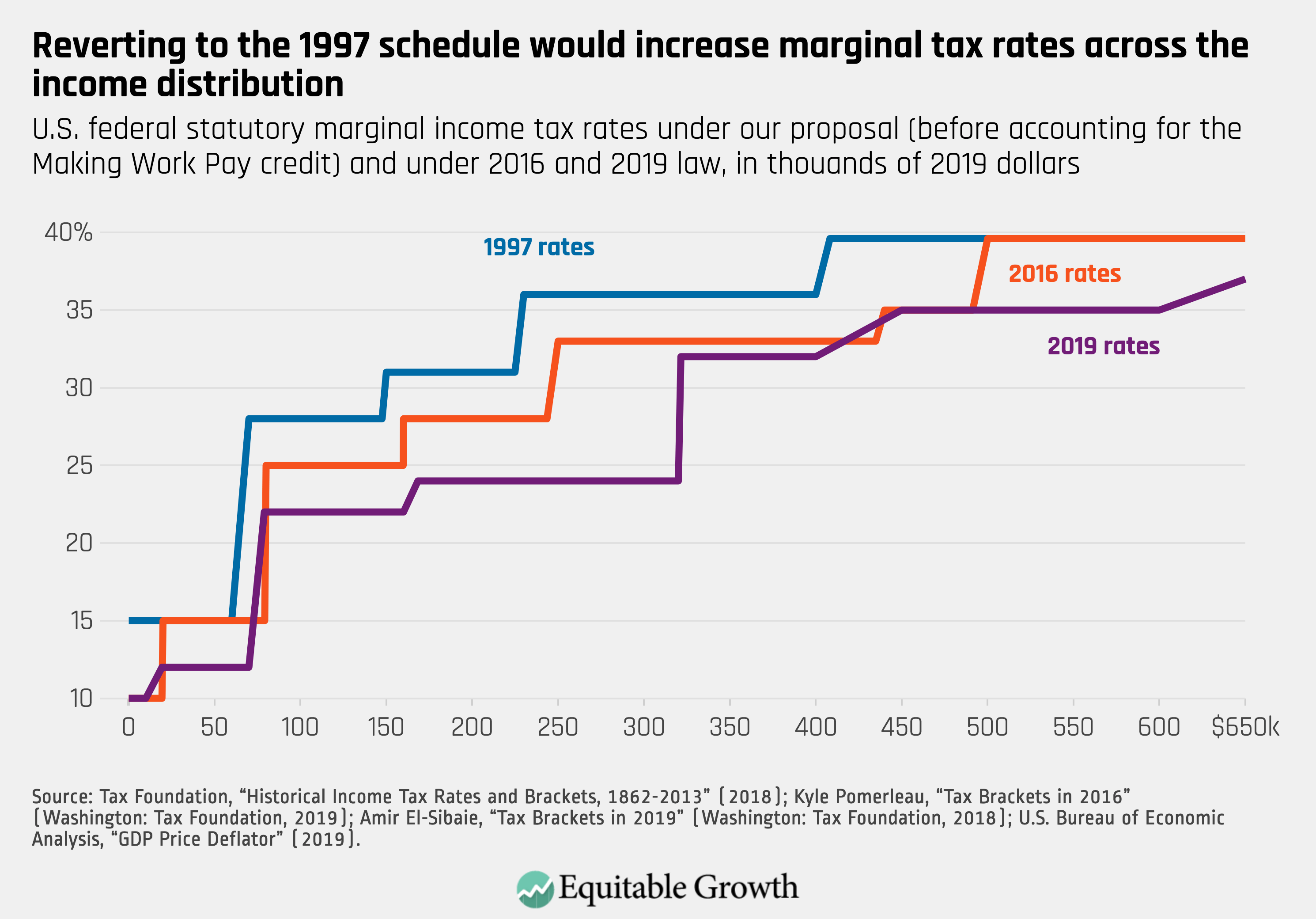

We propose returning the personal tax rate and bracket structure, adjusted for inflation, to where it was in January 1997. For married couples, taxes would amount to 36 cents instead of 24 cents of their 300,001st dollar. For those making $500,000, marginal rates would increase to 39.6 percent from 35 percent.

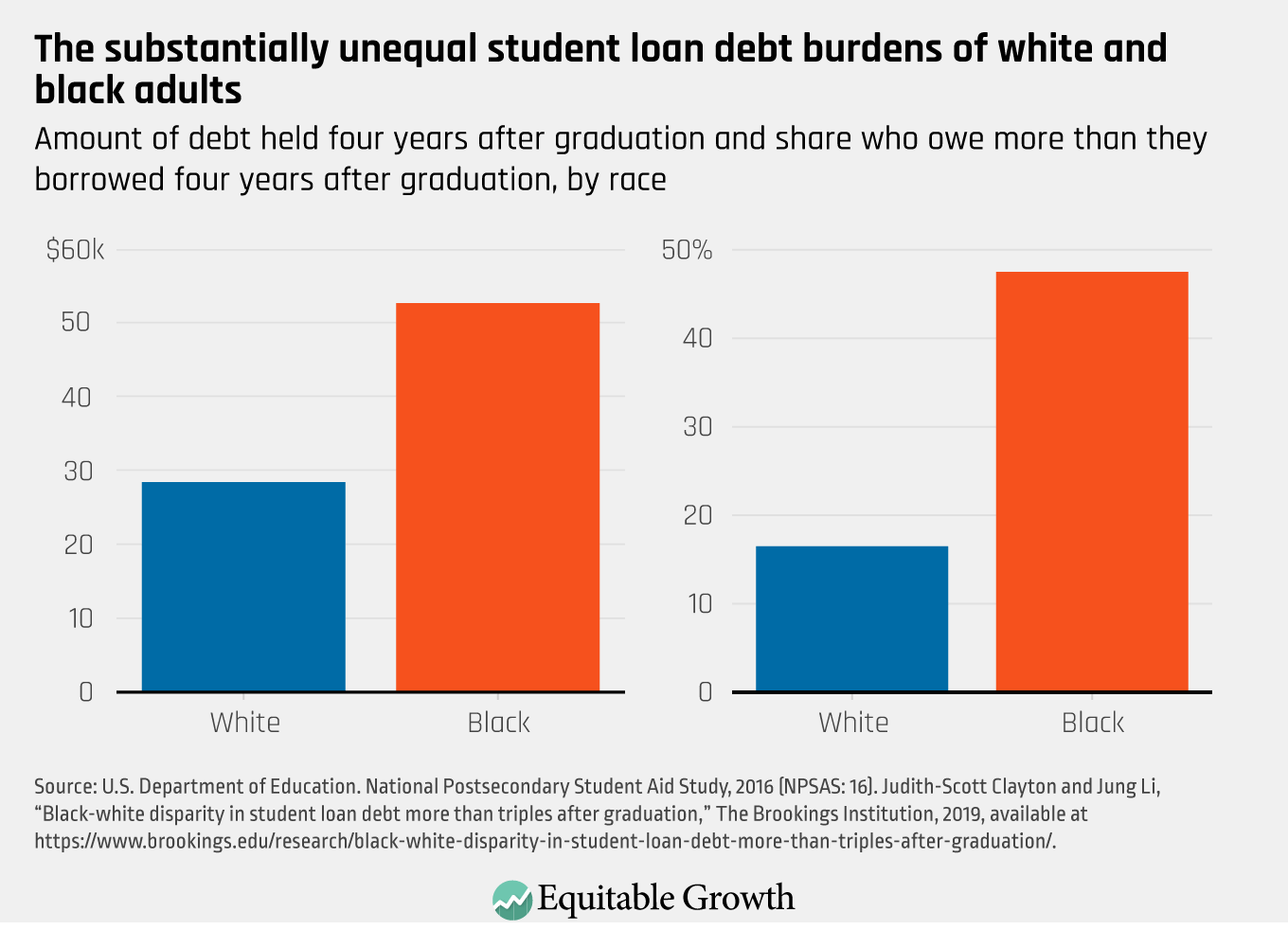

These changes will raise average tax rates on top incomes considerably. Rolling back the 2001 and 2017 income tax cuts would also entail modest increases throughout the income distribution. Under our proposal, a tax credit similar to the Making Work Pay tax credit from the 2009 Recovery Act would offset tax increases for low- and middle-class earners in a targeted way. Figure 4 shows how this change (without the Making Work Pay credit) would affect marginal tax rates relative to the 2016 and 2019 tax rate schedules.

Figure 4

Business income taxes

We propose removing the active business income exclusion from the net investment income tax and repealing the recently enacted deduction for people who receive income from pass-through businesses. These provisions offer lower tax rates on income from some pass-through firms. These changes will increase taxes on private business owners who prevail at the top of the income distribution and ensure parity in the tax rates between people who receive income in different forms.

We also propose taxing nonpublicly listed C corporations at the top personal income tax rate rather than the otherwise applicable corporate rate of 21 percent. This change would prevent entrepreneurs from using retained earnings and deferral as a strategy for avoiding higher income tax rates.

Dividends and capital gains

We propose returning the dividend and capital gains tax rates to their 1997 levels. This change would increase the top federal tax rate to 39.6 percent from 20 percent for the recipients of most taxable dividends. For capital gains, this change would bring maximum long-term capital gains tax rates back to 28 percent from 20 percent today.

We also propose extending the time horizon for preferential capital gains rates to 10 years to treat more carried-interest compensation as wage income while preserving incentives for long-term investment. Dividends, and especially capital gains realizations, are quite concentrated at the top of the income distribution. In recent years, more than 50 percent of taxable dividends and 80 percent of capital gains realizations have gone to the top 1 percent of income earners.5 These changes will increase taxes at the top of the income distribution.

Estate taxes

We propose unwinding the 2001 and 2017 reductions in estate and gift taxation by returning to a 55 percent top rate and setting a $1 million effective exemption. We also propose eliminating the so-called step up in basis at death, a policy that exempts from income tax any capital gains on assets held by a taxpayer at death.

Our proposal also treats charitable contributions and gifts as realization events, meaning that taxes would be due on any unrealized capital gains at that time. Reinvigorating the estate tax should also be paired with careful steps to curtail abusive private business valuations.6 These changes will help reduce wealth concentration, raise revenue, and increase the fairness of the tax system.

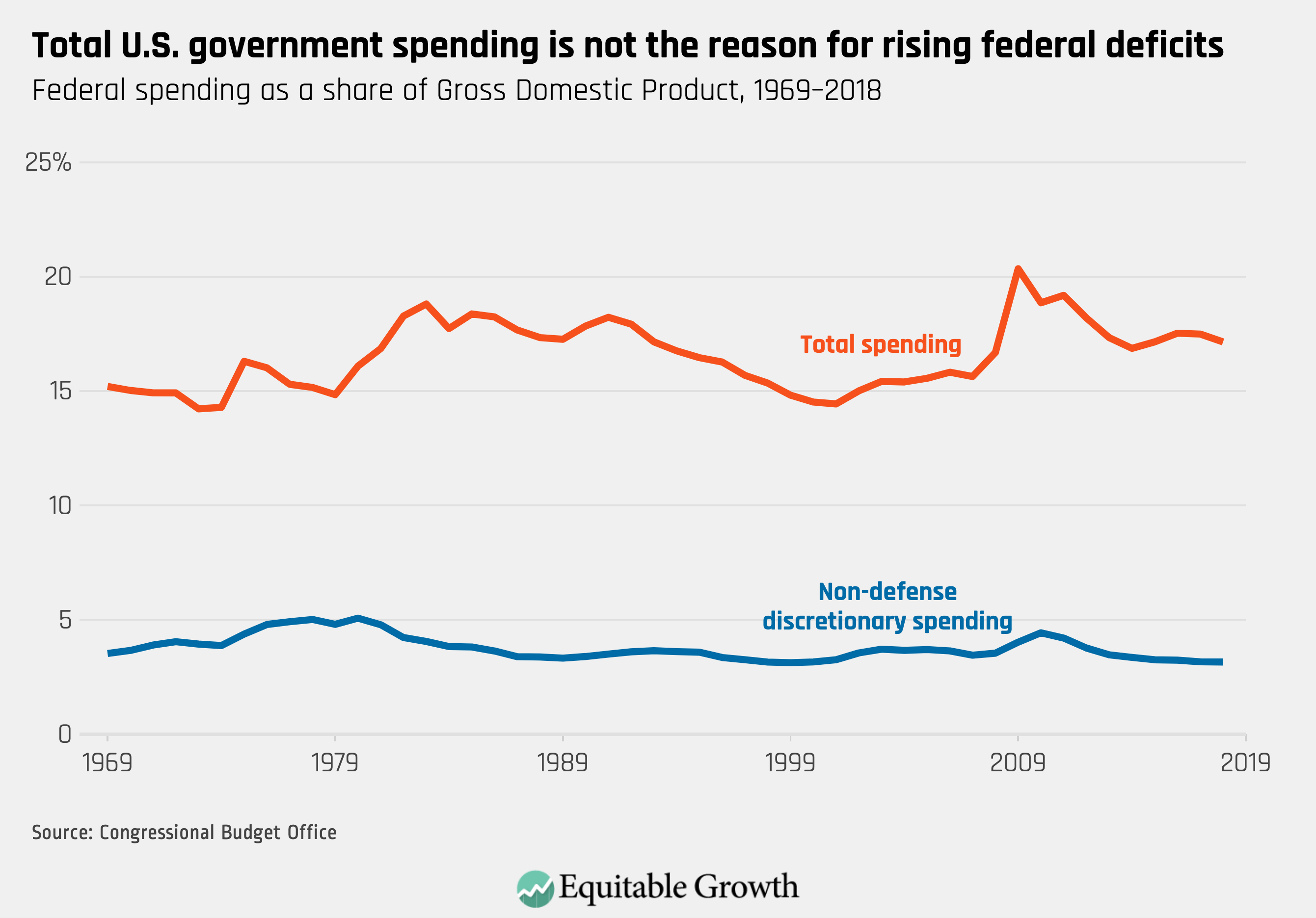

Revenue and distribution analysis

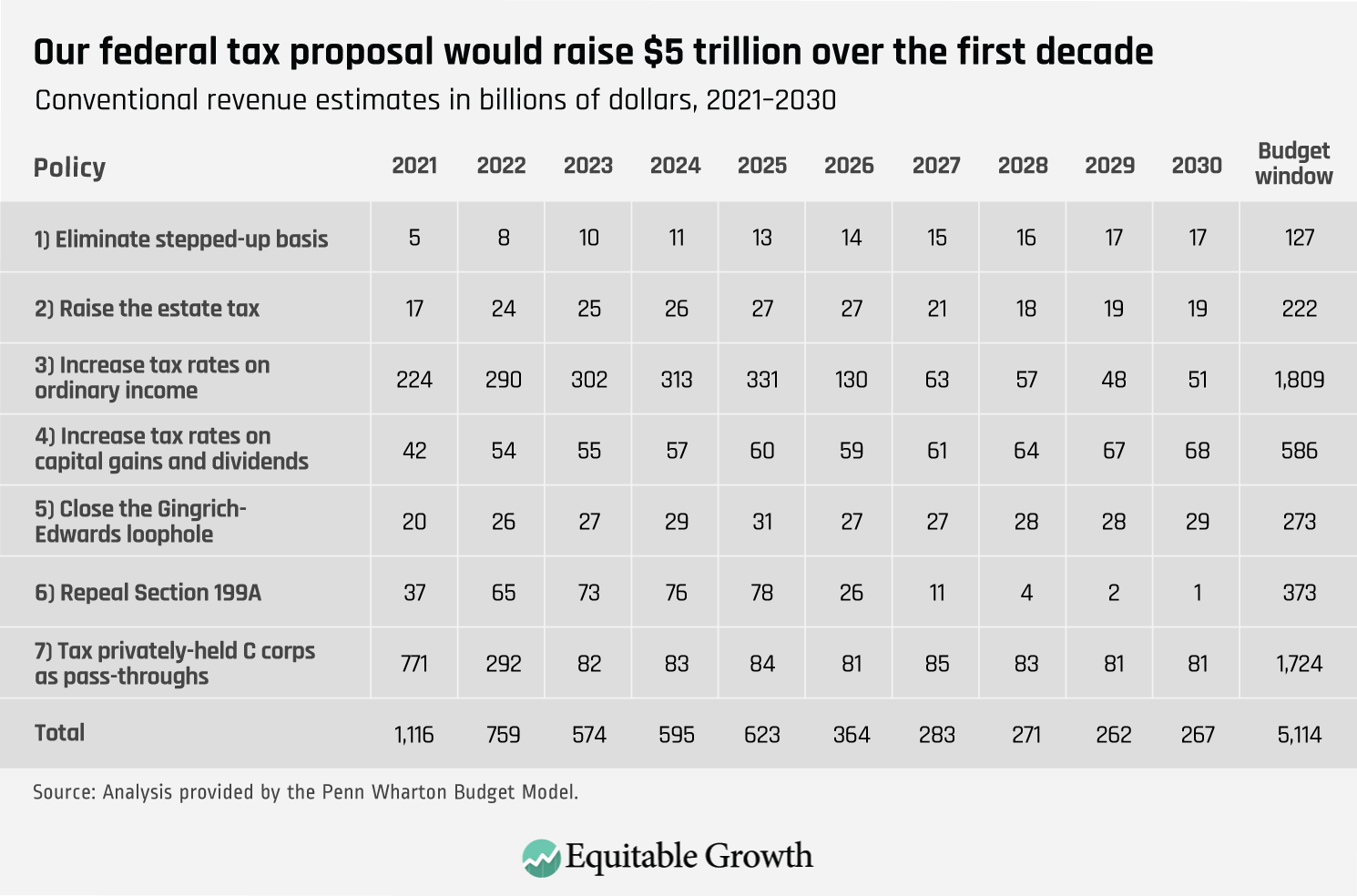

Our proposal would raise $5.1 trillion over the next 10 years, according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model. The largest contributors to this increase are $1.8 trillion from the increase in tax rates on ordinary income net of the Making Work Pay credit, $1.7 trillion from taxing privately held C corporations as pass-throughs, and $0.6 trillion from increasing taxes on capital gains and dividends. Without the Making Work Pay Credit, the other changes raise $6.9 trillion, with the increase in tax rates on ordinary income accounting for $3.6 trillion instead of $1.8 trillion. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

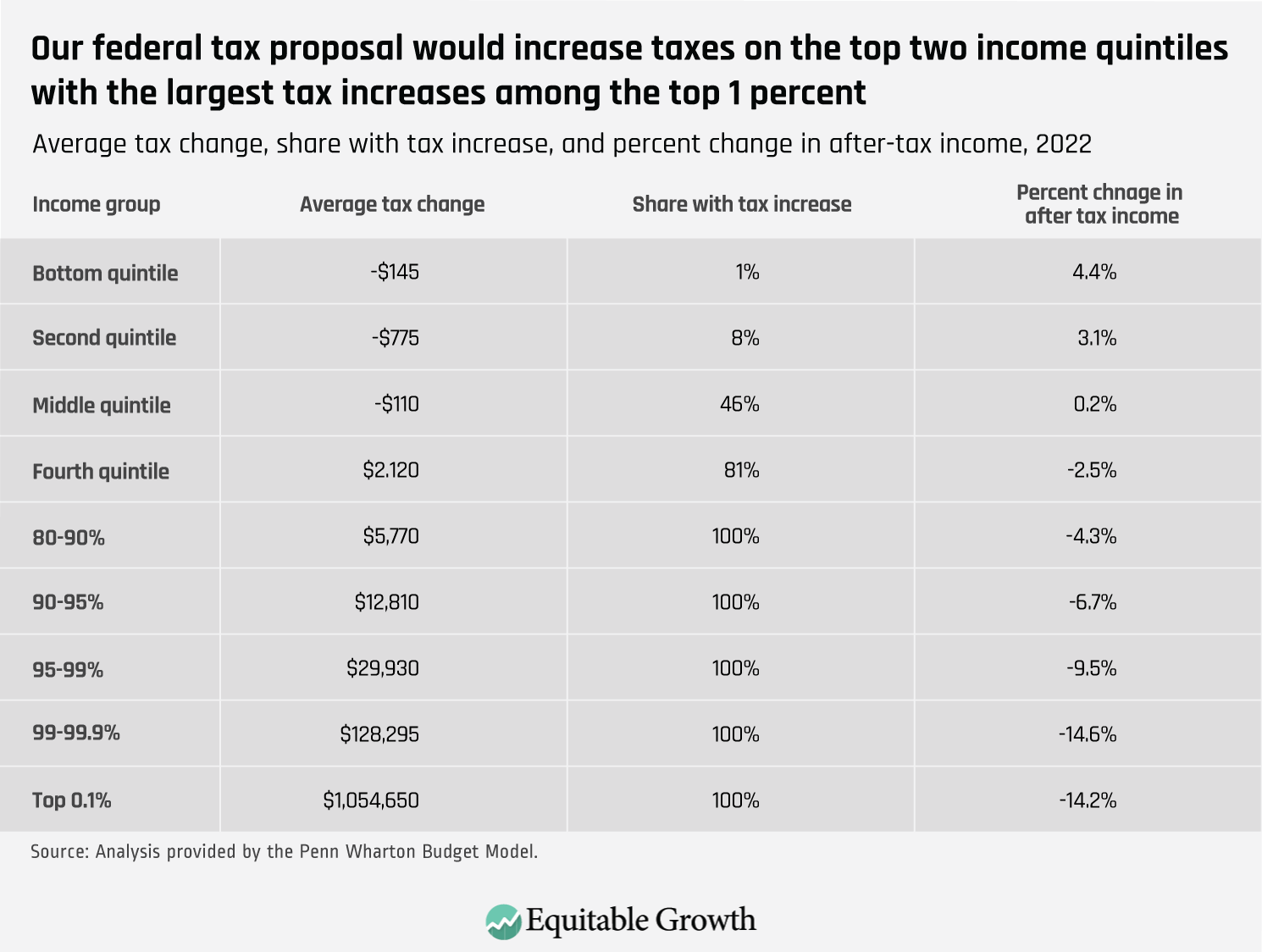

Most of the revenues from our proposal come from the top of the income distribution. Specifically, the top 10 percent, 5 percent, 1 percent, and 0.1 percent account for 83 percent, 70 percent, 46 percent, and 23 percent of the increase, respectively. The average after-tax income of the top 0.1 percent, whose average pretax income is $2.1 million, would fall by 14 percent, or $220,000. The average after-tax income of the fourth quintile, whose average pretax income is $98,000, would fall by 2.5 percent, or $2,000. In contrast, the bottom three quintiles do not face tax increases due to the Making Work Pay credit. The estimates highlight the extent to which the changes since 1997 have been concentrated at the top. (See Table 2.)

Table 2

Addressing potential criticisms

In 1997, tax revenue was 3 percent higher as a share of GDP. Top federal rates were approximately 40 percent, tax rates on labor and capital income for entrepreneurs were more closely aligned, and the tax base was broader. The subsequent evolution in pass-through income has raised the stakes in how we tax nonwage income, especially for closely held firms. Our proposal would directly address this development in aligning the taxation of private C corporations with pass-through businesses.

One might criticize this proposal for jeopardizing economic growth. Recent research, however, about the growth effects of taxing top incomes suggests this criticism is overstated. In response to the dividend tax cut of 2003—one of the exact policies we propose to roll back—economist Danny Yagan at the University of California, Berkeley finds a large increase in payout and no change in investment in a large sample of private firms, whose ownership likely skews toward top incomes.7

One of the co-authors of this essay finds that tax changes of the magnitude seen in the post-World War II period for top earners have small impacts on employment growth.8 These findings suggest returning to modestly higher top income tax rates and to a dividend tax closer to the personal rate will have small effects on investment and growth. Indeed, estimates of this plan prepared by the Penn Wharton Budget Model suggest it would have no discernable impact on growth in the first two decades but ultimately would increase growth by 2050.

While some critics may cite large taxable income elasticities as evidence for large distortions, Matthew Smith at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, UC Berkeley’s Yagan, and the two co-authors of this essay document a large shifting response to the difference between top entrepreneurial income treated as wages versus that treated as profits.9 Prior to the 2017 tax reform, the tax-preferred form was pass-through profits because this form benefited from lower social insurance and passive investment income tax.

Because much of this income is better thought of as reflecting human capital, the literature documenting small labor-supply responses to income taxes applies to most pass-through income as well. Proposals that align tax rates on different income sources receive additional support in the literature that finds large reporting responses to tax changes.

A second criticism is that this proposal is modest. Indeed it is! We view it as a point of departure for tax reform and are sympathetic to additional steps that focus on top incomes and enforcement. We view our approach as complementary to more ambitious revenue-raising proposals, such as a national value-added tax, a carbon tax, and a wealth tax.

—Owen Zidar is an associate professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University. Eric Zwick is an associate professor of finance at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business.