Weekend reading: Wages and work edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

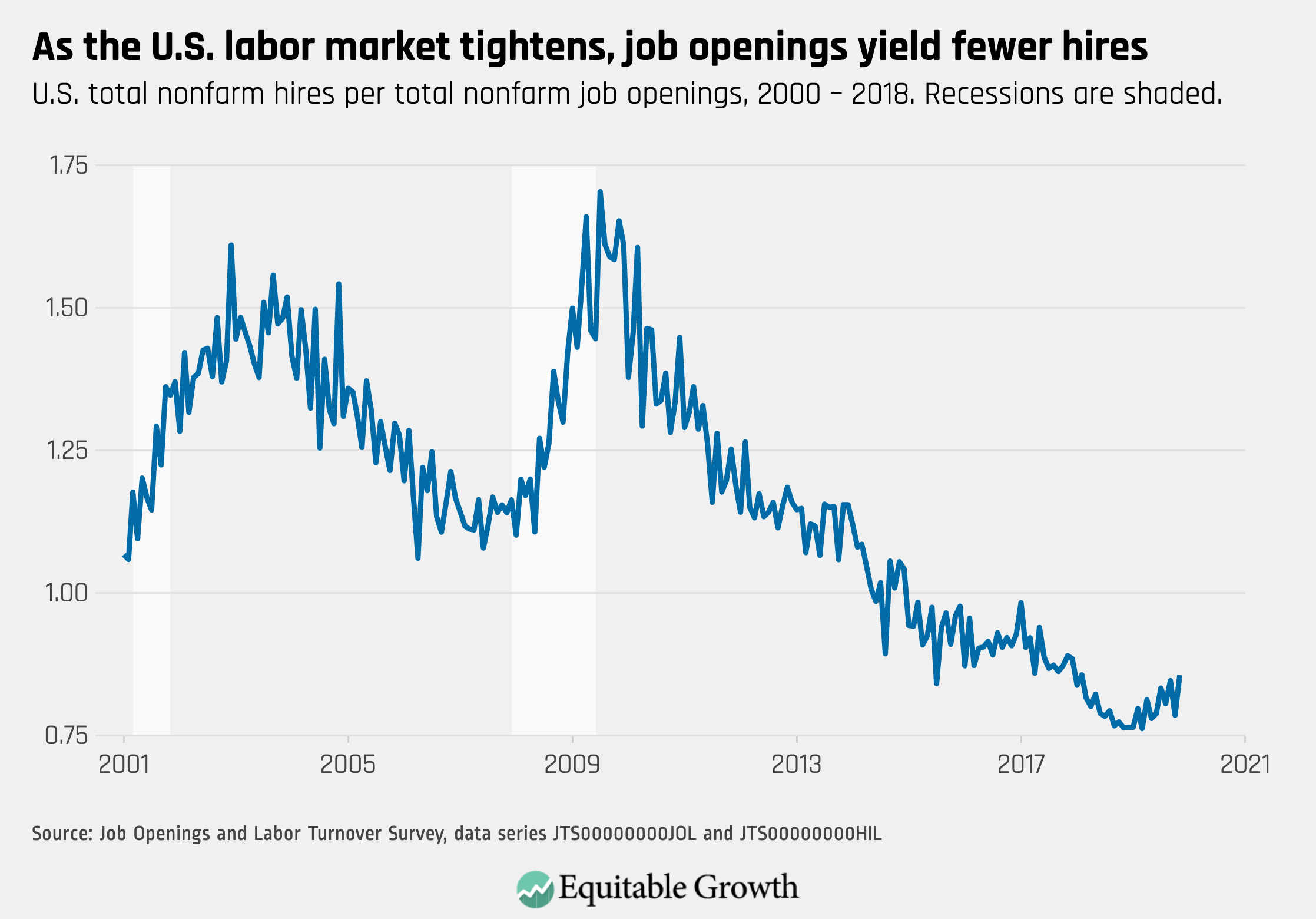

Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS. Today, the BLS released the data for November 2019, showing that the number of new hires remained about the same, while the rate of job openings decreased slightly. Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn put together four graphics to illustrate this and other observations about the data.

A new working paper looks at how the extension of the federal minimum wage in the 1960s led to the decrease in earnings differences between black and white workers in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act expanded the federal minimum wage to new industries such as agriculture, restaurants, nursing homes, and other service industries—areas where nearly one-third of black workers were employed—wages rose dramatically for workers in these newly covered industries, with no effect on employment. Ellora Derenoncourt and Claire Montialoux show that the impact on black workers was nearly twice as large as the impact on white workers, and argue that their research suggests that “minimum wage policy can play a critical role in reducing racial economic disparities.”

Head over to Brad DeLong’s latest worthy reads for his takes on recent must-reads from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

A few years ago, West Virginia passed stricter work requirements for its supplemental nutrition assistance program—similar to the ones embraced the Trump administration that will go into effect in April—mandating at least 20 hours per week of work or training for work in order to receive access to the safety net program. Campbell Robertson of The New York Times followed up on the new state-level regulations, looking at how the change affected both state employment rates and the daily lives of people who rely on the program. “The policy seems straightforward,” he writes, “but there is nothing straightforward about the reality of the working poor, a daily life of unreliable transportation, erratic work hours and capricious living arrangements.” His investigation found that employment rates have not increased noticeably under the restrictions—often the argument for implementing such a change—while the most apparent impact has been “at homeless missions and food pantries, which saw a big spike in demand that has never receded.”

“If there’s one thing many Americans agree on,” write Scott Lanman and Stephanie Flanders for Bloomberg, “it’s the importance of education as a bedrock of the U.S. economy.” In an episode of the news outlet’s Stephanomics podcast, education and the disparities in outcomes and resources between school districts as a result of funding being left to state and local governments takes center stage. The episode looks at how difficult it can be to improve access and quality of education when districts are subject to the whims of the real estate market and demographic shifts—and what states can do about it.

As the gig economy expands further, where can we expect it to stop? The gigantic spread of app-based companies into various aspects our lives arrives with drastic consequences for many full-time employees, from taxi drivers to bellmen to chefs. “The service sector, in contrast to manufacturing, is just beginning to contend with automation and technological displacement—in the form of robots, apps and algorithms,” writes E. Tammy Kim in The New York Times. And while it seems there may be no limit to where the gig economy can go, how the service sector adapts and reacts to app-based employment may act as a guide for the future, Kim posits that “only a broad-based fight for fair treatment and lawful classification [as full-time employees, not contractors] can dismantle the ideology of labor built into Uber and its ilk: that all workers should be as productive and loyal as lifetime employees, and expect nothing in return.”

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “JOLTS Day Graphs: November 2019 Report Edition” by Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn.