Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

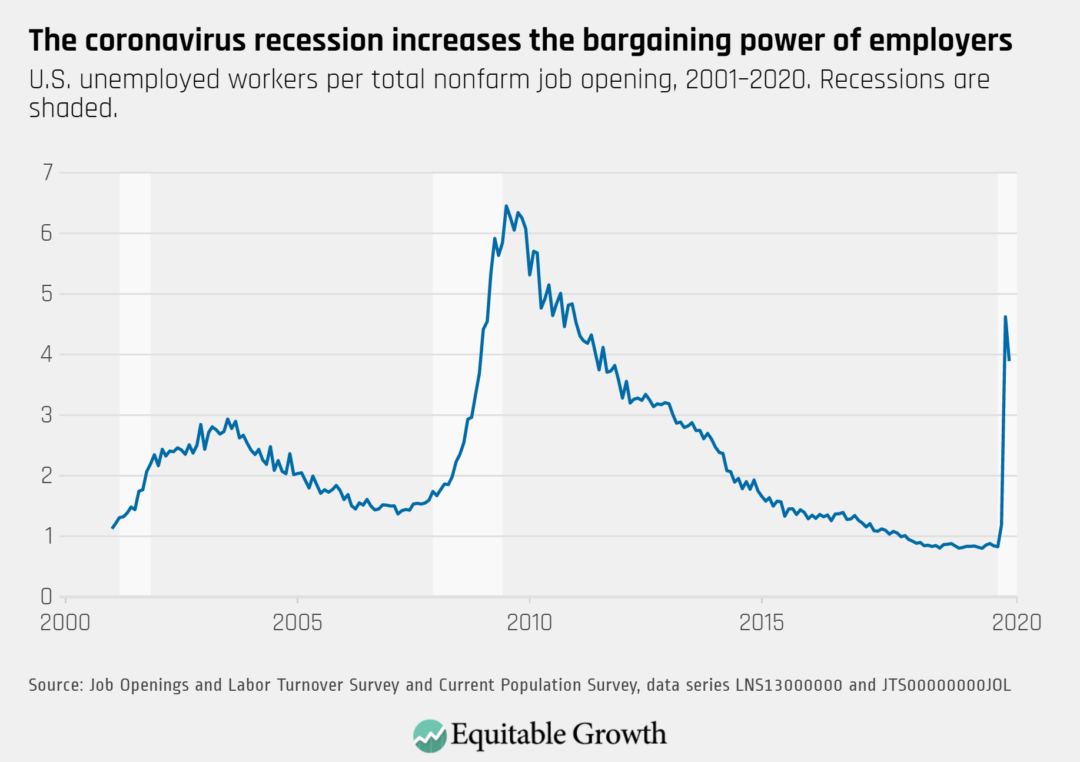

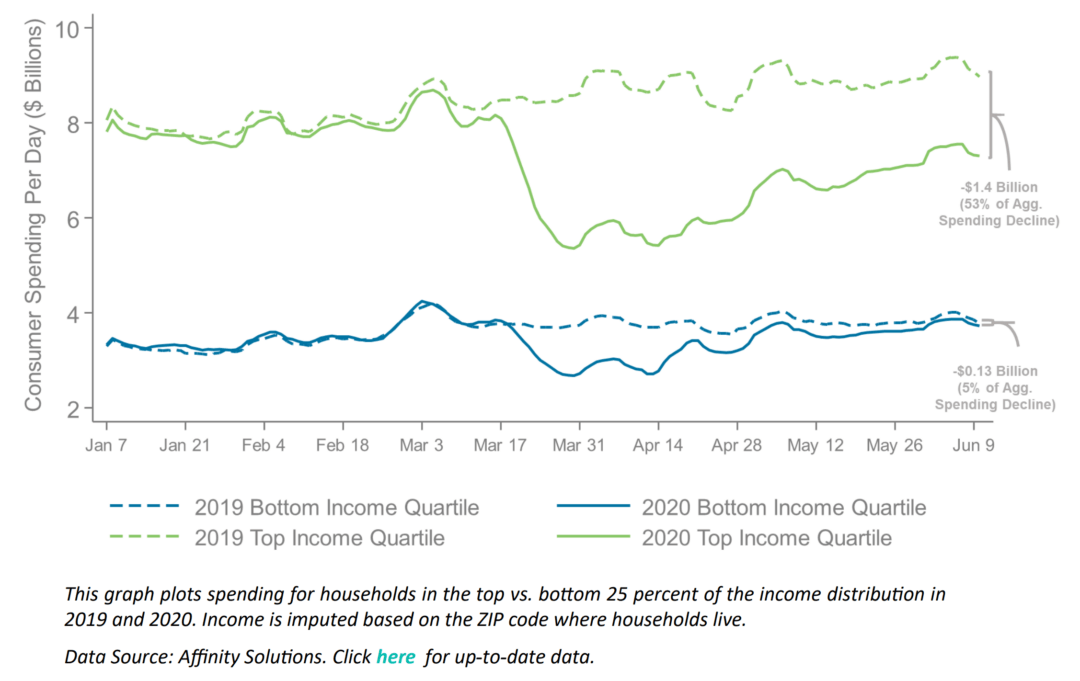

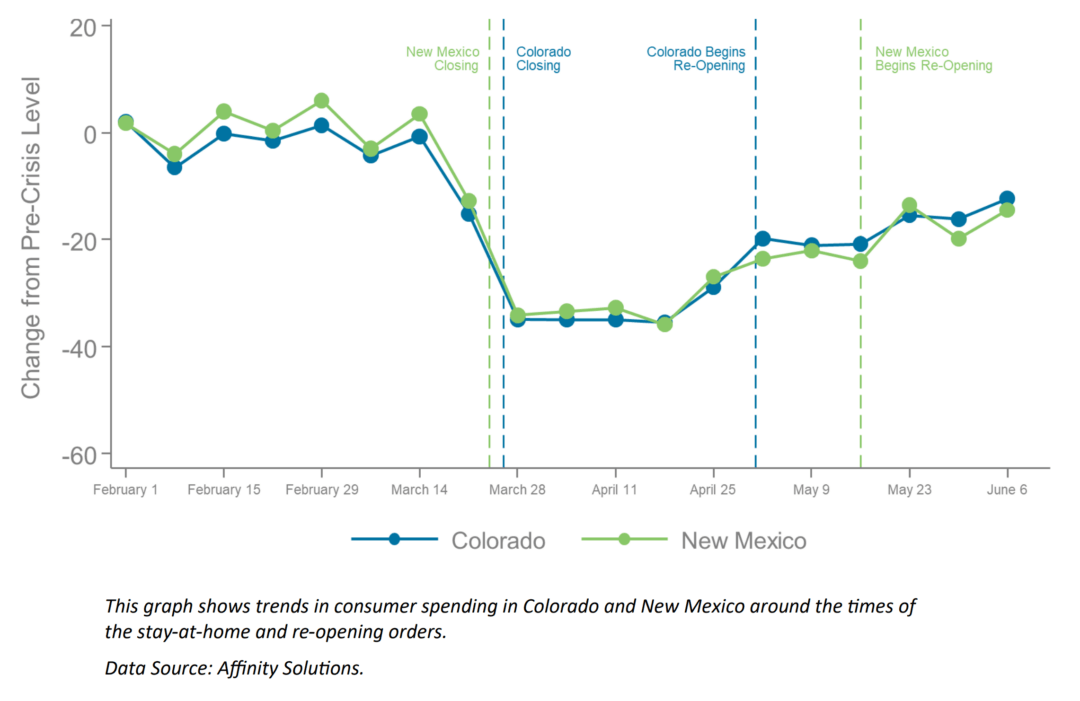

1. Put me down as saying that we require, right now, not just additional social insurance payments but additional government purchases, additional government employment of test-&-tracers and nurses, plus powerful steps to boost all forms of investment spending while in-person consumption is depressed. Read Liz Hipple and Amanda Fischer, “Enhanced U.S. social insurance will be necessary until the coronavirus recession recedes,” in which they write: “Raj Chetty and his Opportunity Insights colleagues … [find that] U.S. consumer spending fell dramatically over the past few months, driven by public health and safety concerns … [that] are keeping people, especially those in high-income households, away from purchasing in-person services, indicating that until people feel safe engaging again in in-person services such as dining out or getting haircuts, consumer spending on services—which accounts for 66 percent of all consumer spending—will not meaningfully rebound … To fix the U.S. economy … [requires] first fix[ing] the U.S. public health crisis. Merely announcing that the economy is “reopened” will not make it so … Investing in social insurance programs—such as the expanded unemployment benefits enacted by Congress in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act—is the best way to mitigate economic suffering during the recession, rather than stimulus measures targeted toward businesses or the rich … The fall-off in consumer spending is being driven by high-income households, particularly in areas with high rates of COVID-1 … As of May 31, two-thirds of the total reduction in credit card spending since January was from households in the top 25 percent of the income distribution, whereas spending by households in the bottom quartile had returned to normal levels.”

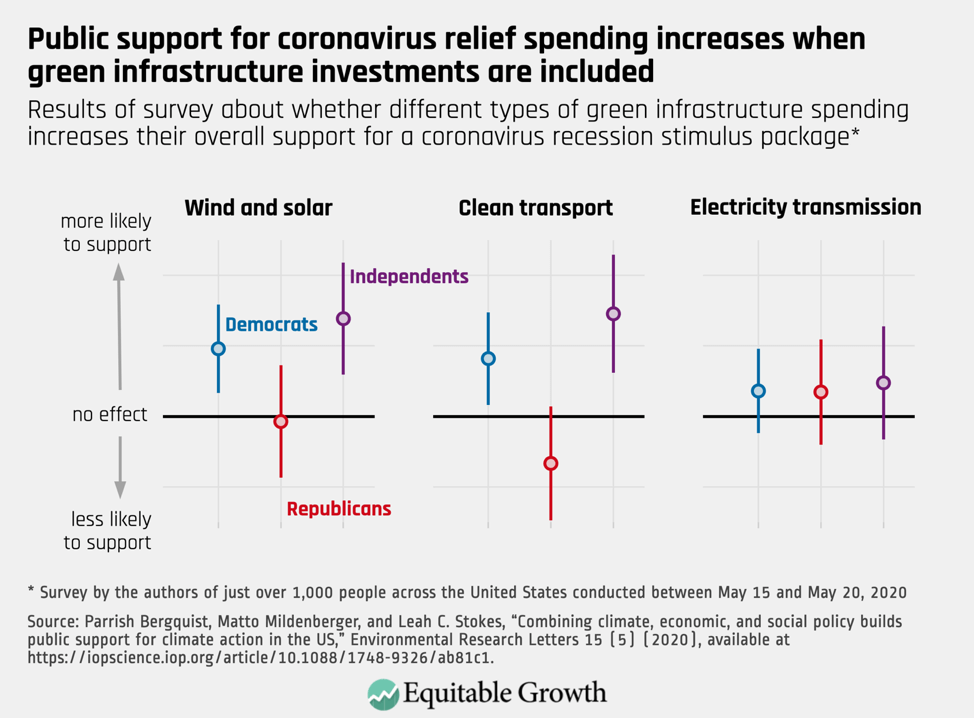

2. There is potential political support for, and there is certainly both technocratic justification and fiscal space for hitting both the economic recovery and the global warming fight together through coronavirus repression relief. Read Parrish Bergquist, Matto Mildenberger, and Leah Stokes, “Americans want green spending in federal coronavirus recession relief packages,” in which they write: “We launched a nationally representative survey of slightly more than 1,000 people between May 15, 2020 and May 20, 2020 … [the survey finds that] the public supports green stimulus but not at the expense of broad economic relief. Our experimental results show that including green infrastructure spending increases support for a coronavirus relief package. Support for wind and solar investments and for clean transportation investments is particularly strong. Including these measures increases support by 8.5 percentage points and 6.1 percentage points, respectively. Notably, including electricity transmission investments does not cause a change in support for the package.”

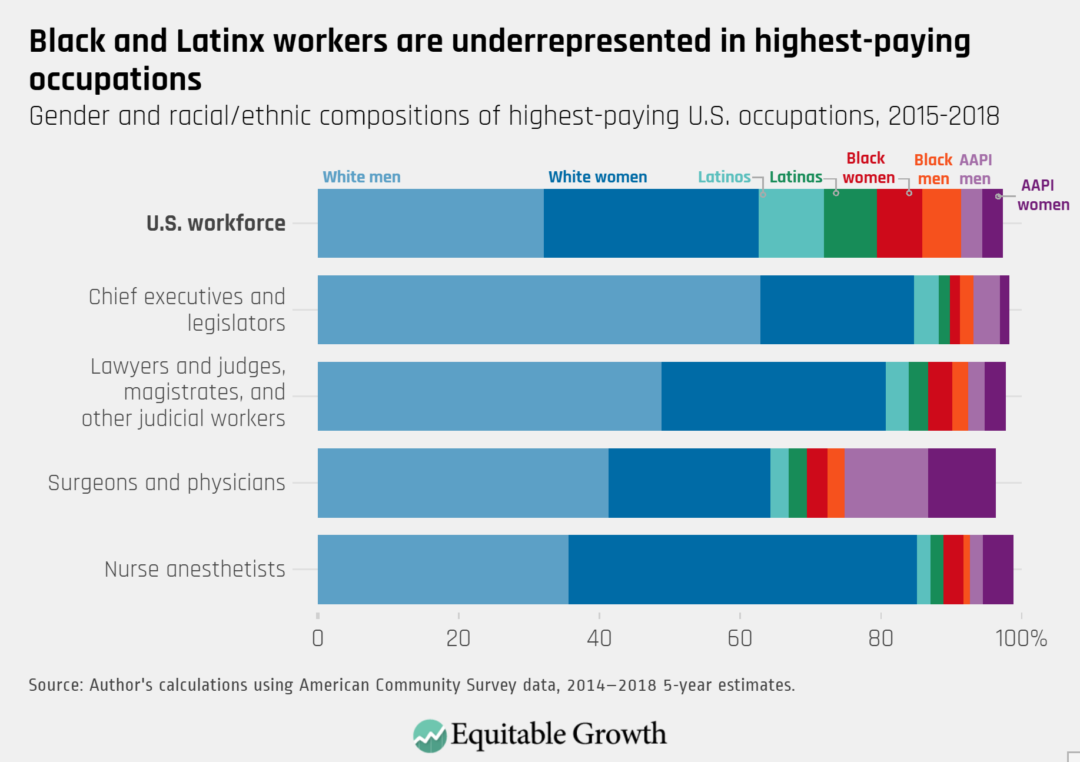

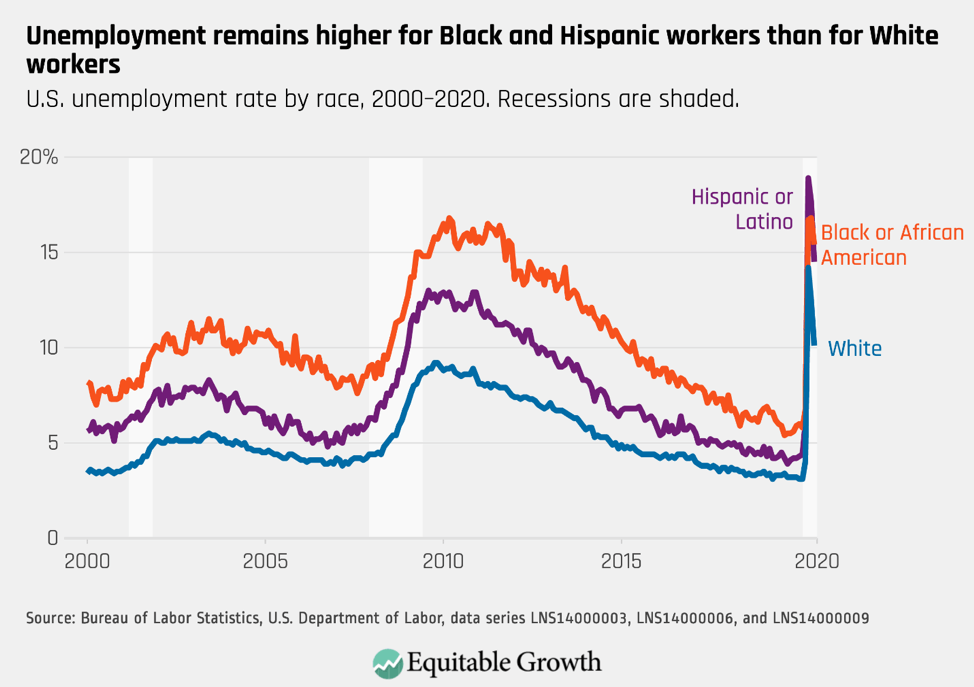

3. Very much worth reading is Heather Boushey, “The link between structural racism, the coronavirus recession, & economic inequality: Weak Institutions,” in which she writes: “The evidence that inequality harms is all around us. The vulnerability of communities of low-income, as well as Black, Latinx, and Native American families to the effects of the coronavirus and the recession is stark. The same living and working conditions that obstruct people’s economic opportunities—the lack of access to affordable housing, inadequate healthcare, unsafe working conditions, the lack of paid sick leave—expose them in greater numbers to sickness and death from COVID-19. The failure to have effective institutions that protect all workers means our entire economy is less resilient—and more economically unstable as a result … This brings us back to trust. Government must work on behalf of low-income, Black, Latinx, and Native American people and make sure their needs are truly reflected in the policy agenda. People must see that they can both develop and deploy their talents and skills in the economy and that those at the top are not encouraged to subvert outcomes to benefit themselves rather than our economy and society writ large. People must have both confidence and proof that they are protected from oppression and state-sanctioned violence. As we look to strengthening our democracy and recovering from this coronavirus recession in the years to come, core to any economic agenda must be to confront the role that effective institutions play in fostering growth that is strong, stable, and broadly shared. If large portions of our population can’t trust the government to act on their behalves, then we need to acknowledge our government isn’t working the way it needs to.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

1. I have been convinced by the work done by Austan Goolsbee, and by many others, that the fall in aggregate demand when the 2019 coronavirus pandemic hit was larger than the fall in aggregate supply. But there is a fall in aggregate supply. And there is a profound shift in demand away from close-contact indoor activities. I had originally hoped that the shocks would be temporary, on the order of magnitude of a quarter of a year, as we got the coronavirus on the run and got test-trace-isolate systems up and running so that our society and economy could return to normal. But it now we appear to be currently running at 200,000 new coronavirus cases a day. Of these, our testing system is catching only 1/3 at best. At this pace we face at least another four months of the current situation: a very high savings rate and a large shift in the composition of demand as well. We could reattain and then maintain something close to full employment if we shifted workers accordingly. The government could be doing a lot to incentivize the rapid move of labor into investment goods production, public-goods production, and low-contact production. But the government is not. And there are no channels for the private economy to respond appropriately given that the largest shock component is not an aggregate supply or a demand composition but rather an aggregate demand shock. Thus I agree with the very smart Muhamed El-Erian here: we are unlikely to see much of a recovery bounceback in the third quarter. We may not see any at all. Read Mohamed El-Erian, “Covid-19: Sunny Third-Quarter Economic Outlook Turns Cloudier,” in which he writes: “A few weeks ago, the expectation was that the onset of the third quarter would mark the close of a highly damaging and uncertain second quarter for the U.S. economy and, importantly, herald a sharp and durable reversal. Instead, with health concerns forcing a growing number of states to either stop or reverse their reopenings, and with some businesses and households withdrawing from active economic re-engagements, a cloud is now forming over the third quarter, threatening the depth and breadth of the economic recovery. With an initial phase of seemingly healthy reopenings, and with government relief measures in full force, high-frequency indicators of economic well-being (household confidence, new jobs and retail sales) started improving in May or deteriorated at a slower rate (jobless claims). Such absolute and relative improvements were countering what was shaping up to be a brutal set of economic data for the second quarter as a whole, including the largest contraction in gross domestic product on record. But with a continuing uptick in economic data that repeatedly beat consensus expectations, the thinking was the hit to this year’s GDP could be contained to 5 percent to 8 percent, with the prospects of recovering the entire loss of output in 2021 … Since then, however, confidence in improving high-frequency data has been dented by indications that the “R-naught” of Covid-19 … has increased above 1 once again in a majority of states … Consistent with these developments, the highest-frequency indicators of household economic activity, such as mobility and restaurant bookings, have already flattened or started to head back down in a growing number of states.”

2. The relative poverty of emerging market economies means that, because of less effective indoor heating and cooling systems, their interior spaces tend to have more ventilation and so are a lot less like batcaves than are interior spaces in the global north. So far, at least, this has meant the 2019 coronavirus pandemic outbreaks in emerging markets appear to be less serious and virulent than outbreaks in poor neighborhoods in global north economies. And the oil sheikhdoms of the Middle East, where urban indoor cooling systems are very effective, may be the example that tests and proves the rule—via the virulence of their 2020 coronavirus pandemic outbreaks. On the other hand, they do have less effective governments, and less societal wealth to mobilize. Michael Spence and Chen Long, however, worry that Florida, Texas, and other states will make up another example that tests the rule, and proves it by developing the worst 2020 coronavirus outbreaks in the world because effective indoor cooling systems in a hot summer come close to turning the spaces where people are into a giant network of coronavirus-friendly batcaves. Read Michael Spence & Chen Long, “Florida as a Developing Country,” in which they write: “The latest data on new infections in Florida suggest that cases are doubling at a rate below 19 days, which puts the state’s outbreak firmly in the “uncontrolled” phase. And a similar recent pattern can be found in Texas and several other states … The explanation for the deepening crisis in developing countries is obvious: many lack the economic, medical, and fiscal resources with which to contain the virus and support their populations through an extended lockdown. But these reasons cannot reasonably be applied to an advanced economy such as the United States … It seems that one part of the country will follow the second-wave pattern, alongside Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, while another part takes a path similar to that of the developing world. But unlike developing countries, these [other] U.S. states will still have the option of changing course, possibly catching up to the second wave, provided that they can muster the political will to do so.”

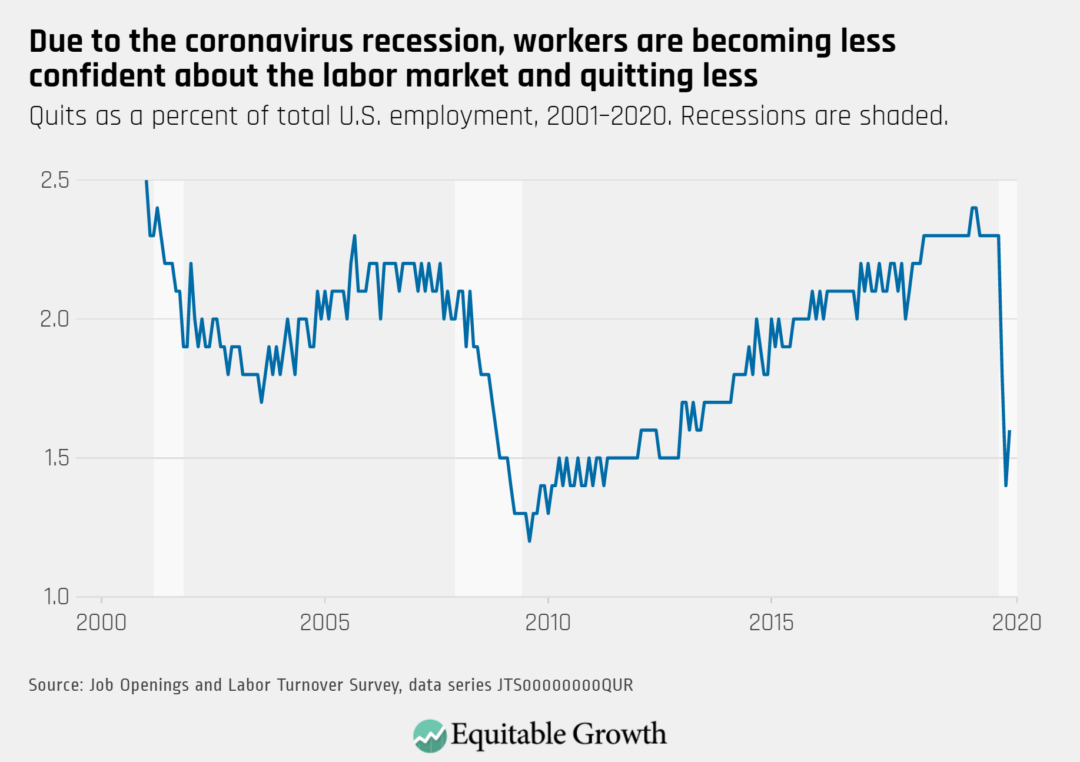

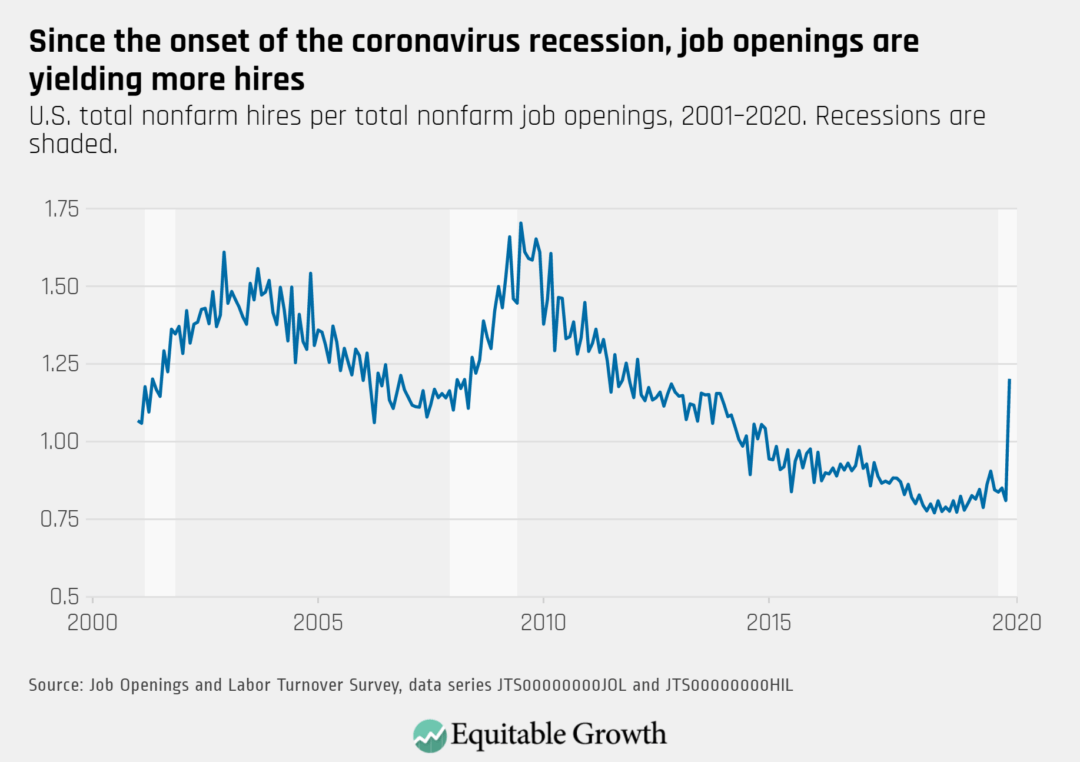

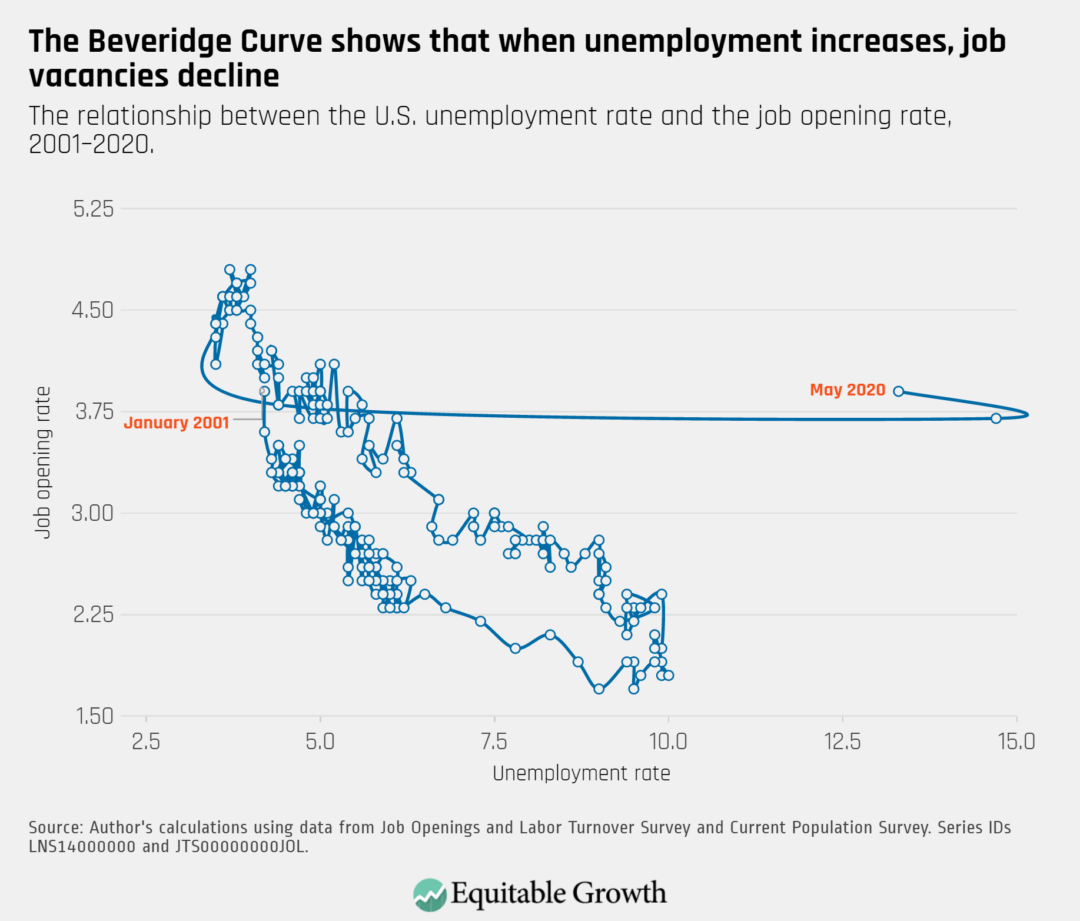

3. The United States having neither contained the coronavirus early nor robust systems for subsidizing jobs at reduced hours is likely to be about to see the worst-in-the-world second wave—save possibly for Brazil. The coronavirus recession may soon be a depression, and the proportion of the population dead may well be worst in the United States as well. Read Martha Gimbel, Jesse Rothstein, and Danny Yagan, “Jobs Numbers across Countries since COVID-19,” in which they write: “Post-COVID job losses have varied dramatically across countries. The United States experienced the largest January-to-April rise in unemployment and along with Canada lost more than 15 percent of employment, amounting to 25 million newly jobless U.S. individuals. Germany, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and Israel lost only 0.7 percent to 4.4 percent of employment—equivalent to 18-to-24 million fewer jobless individuals on America’s population base. Germany and Japan each lost only 0.9 percent of employment as millions of their workers received assistance while working reduced hours under previously established “short-time” work systems. In contrast, employers in the United States and Canada eliminated jobs altogether as the coronavirus spread. South Korea and Australia share strong travel ties with China but contained their outbreaks quickly, experiencing respective employment declines of only 3.6 percent and 4.4 percent, respectively. Hence, job losses have been lowest in countries that either contained the virus early or had robust systems for subsidizing jobs at reduced hours.”