Eliminate banks as the “middleman” for federal anti-recession aid. Cancel all student loan debt. Give workers a say in how their workplaces reopen and empower them to form unions. Provide federal relief to childcare programs to prevent them from shutting down permanently. Get Congress to do its job so the Federal Reserve can get out of the business of making fiscal policy.

These ideas for generating strong, sustainable, and broad-based economic growth and achieving racial justice in the wake of the coronavirus recession were put on the virtual table during a June 25 webinar sponsored by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. “Vision 2020: Focusing on economic recovery and structural change” brought together two panels of experts to discuss short- and long-term policy reforms as part of Equitable Growth’s Vision 2020 project for making transformative ideas to address economic inequality central to the 2020 U.S. economic policy debate.

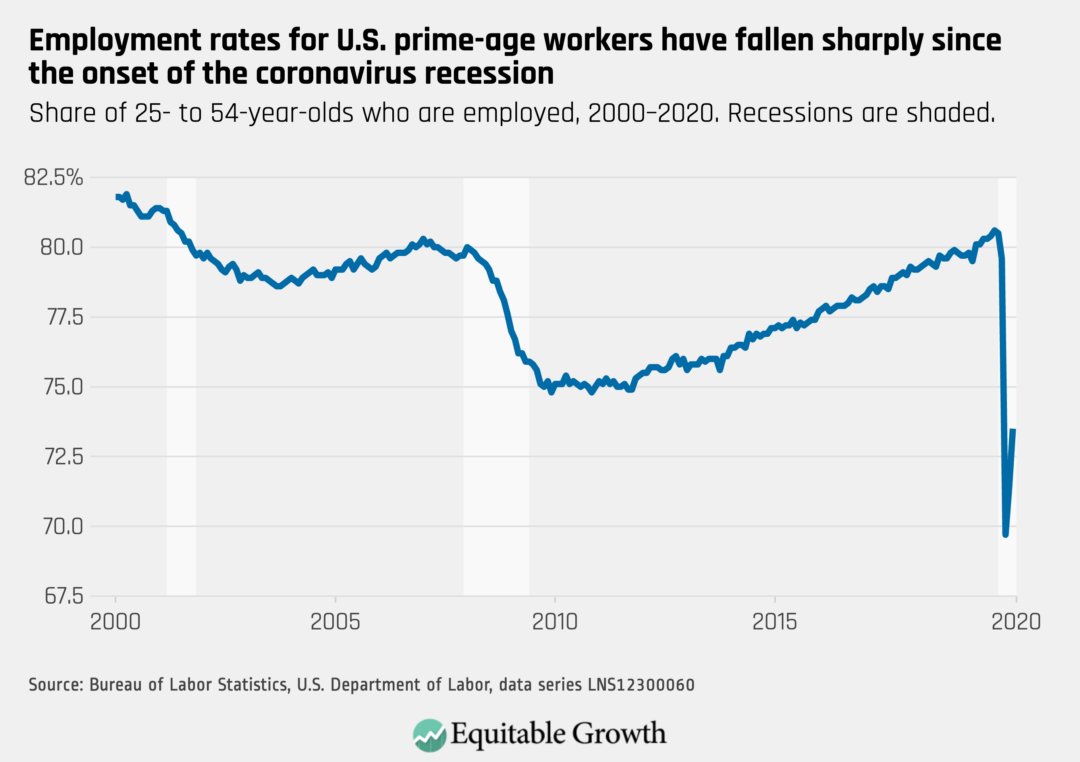

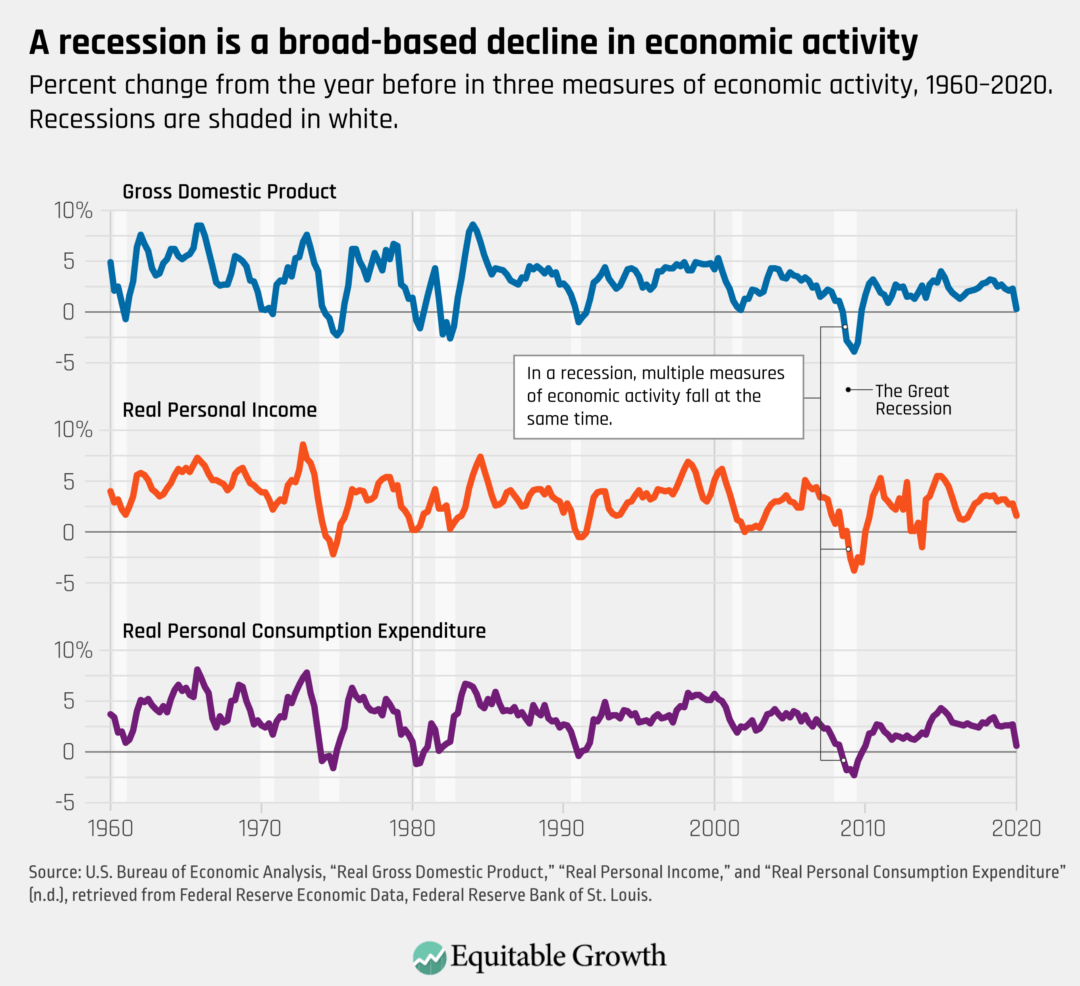

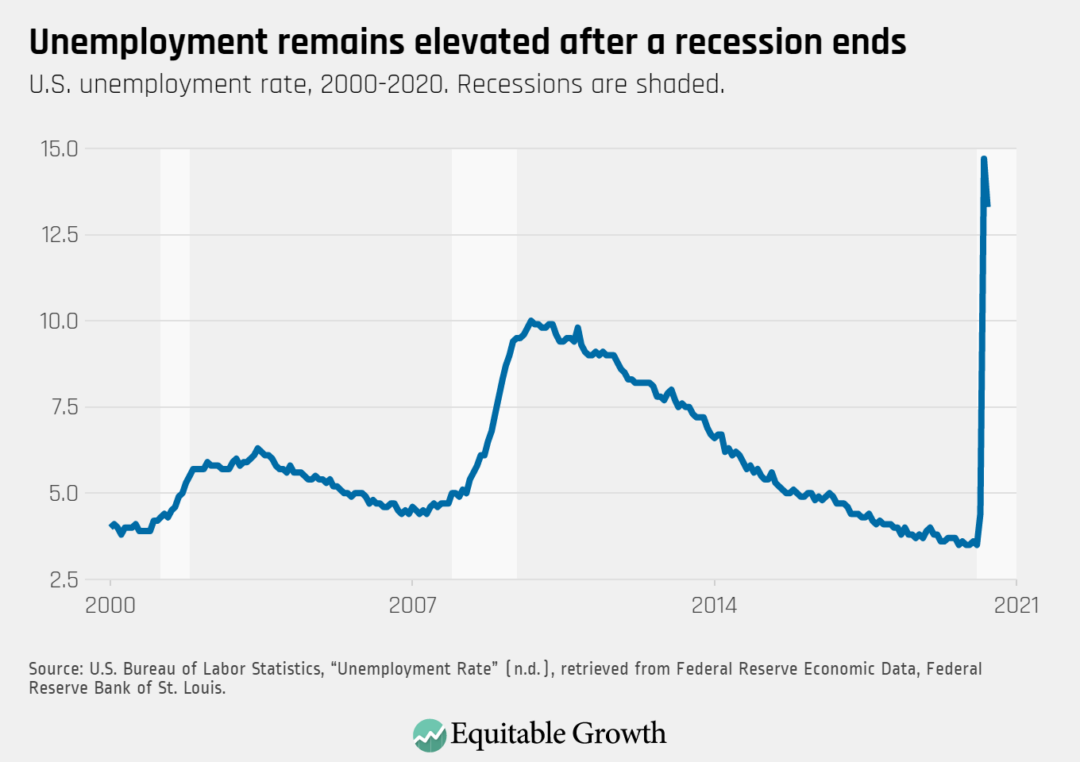

“The recession caused by the coronavirus pandemic is a moment when we are thinking deeply about what’s working in our economy and what’s not working, and, critically, the important role that inequality plays in our economy today,” said Equitable Growth President and CEO Heather Boushey.

Boushey moderated the first of two sessions, a conversation with legal scholars Mehrsa Baradaran of the University of California, Irvine School of Law, and Emma Coleman Jordan of Georgetown University about the Federal Reserve, its role in exacerbating economic inequality, its increasing role in fiscal policy, and the role played by banks in the nation’s response to the coronavirus recession.

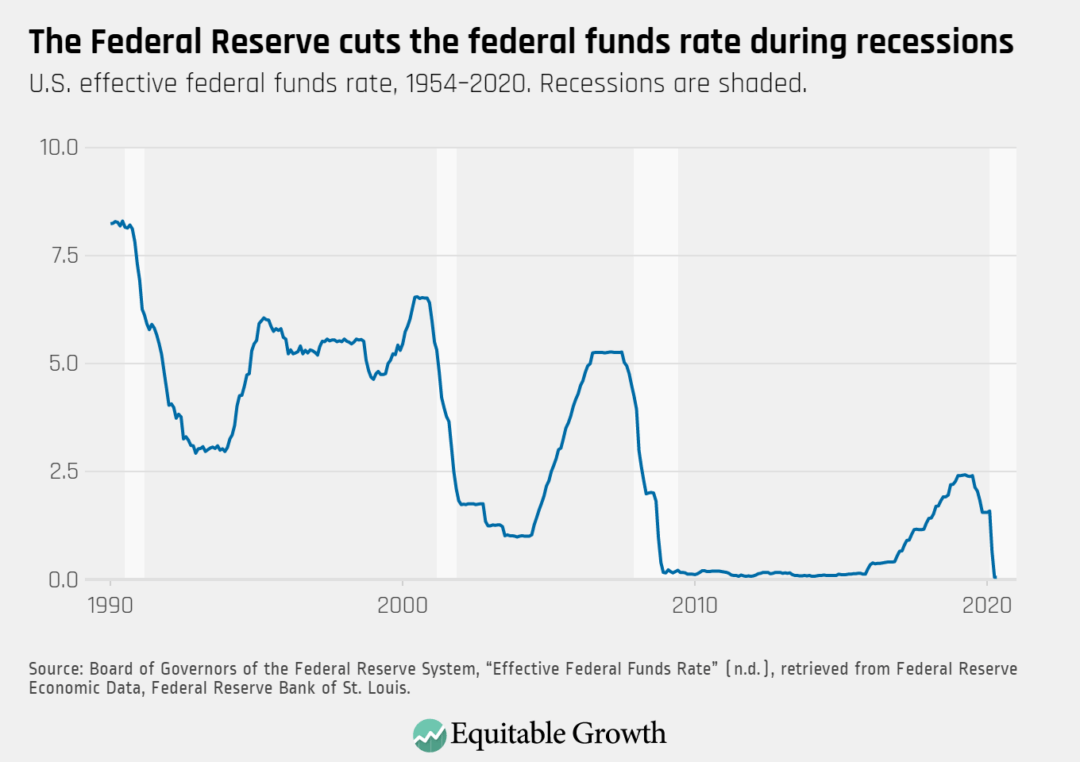

Baradaran noted that when the Fed was created during the Progressive era more than a century ago, part of its mission was to address equity in the economy and ensure broad “access to the tracks on which the economy runs.” But over the past 50 years, she said, the rise of “market fundamentalism” has led policymakers to focus only on markets and monetarism, the theory that the best way to ensure a strong economy is through changes in the money supply.

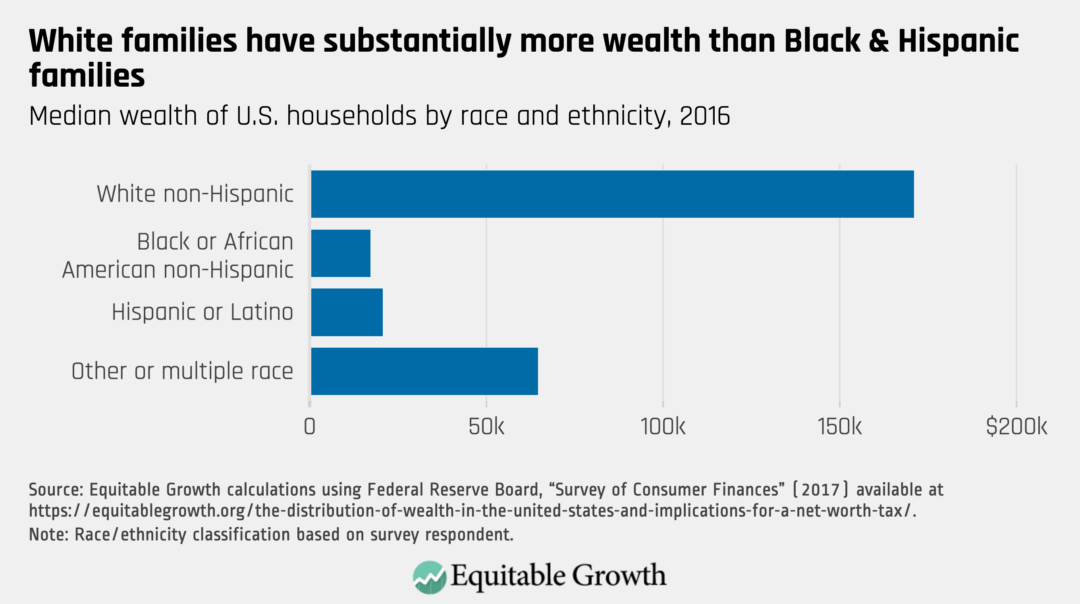

She said “the biggest myth” about the Fed is that when it takes action on monetary policy, “it is a neutral technocratic response to market principles in the abstract, when it is not … the way that the Fed’s monetary responses over the past several decades have massively increased [racial and other income] gaps and created wealth for asset holders in certain markets and deprived it to others is absolutely a political decision. It may not have been framed as such, but it was very much felt by people in the economy.”

Jordan asserted that the Fed is “guided by a set of ideological principles … they are committed to market determinism.” She criticized the Fed’s “orthodoxy that excludes considering individuals, excludes considering race.”

“It’s no surprise,” she said, “that the ideological commitment of the Fed to ignore race as a variable in looking at growth and looking at the economic well-being of Americans produced a kind of cognitive narrowness and blindness … the Fed uses this shield of neutrality to avoid major problems in our economy, and that is the cumulative effect of a long period of racial discrimination, a lot of it government discrimination.”

She said the country needs a new economic bill of rights, and that the Fed needs to be governed by “economic justice, a bold theory that gives us the opportunity to explicitly consider economics and identity, race, gender, and all of the variables that make up the human personality.”

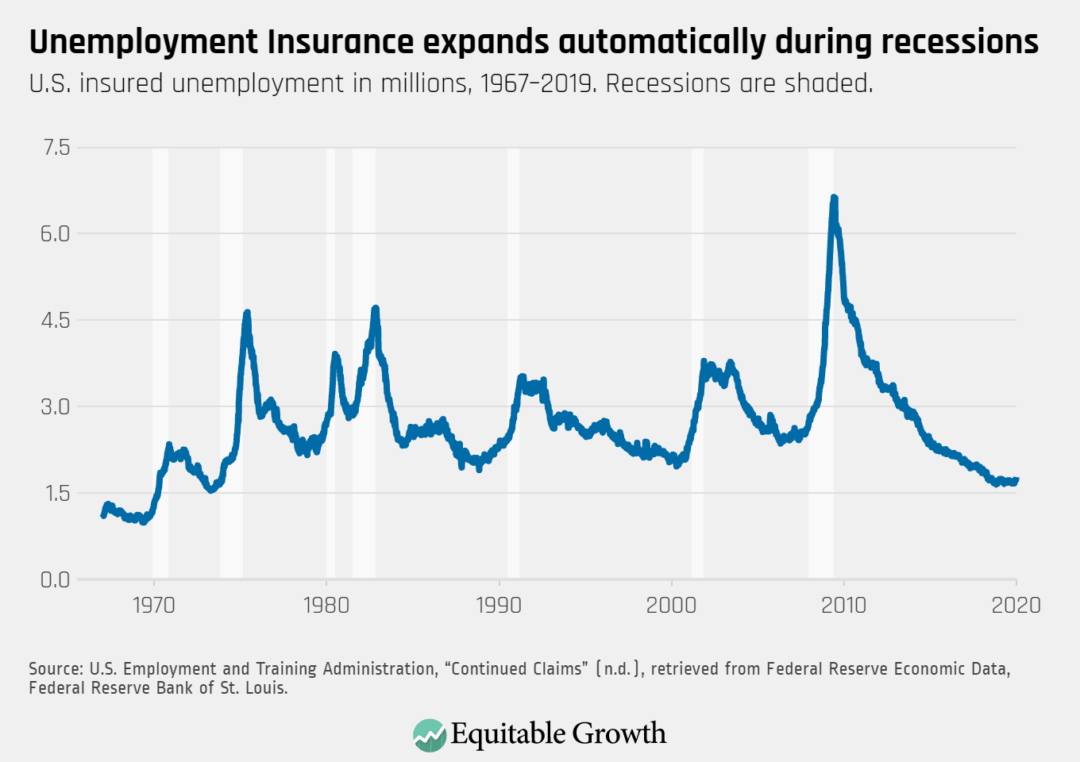

The panelists raised concern that the Fed is engaging in fiscal policy, especially through some of its recent actions intended to prop up businesses, but is not subject to democratic constraints. While the Fed could continue to do this and be made more democratic, the better solution, they agreed, is for Congress to do its job and take responsibility for using fiscal policy to address the recession.

Both experts called for ending the use of banks as the channel through which the federal government provides aid to businesses and consumers in recession-rescue efforts. They said banks disadvantage small businesses, are not accessible to unbanked recipients, and feed cronyism by allowing businesses with which they have a prior relationship to go to the front of the line for aid.

Prejudice toward localism and using the private sector, said Baradaran, leads to an assumption “that the Fed has to use banks as a middleman.” She called for creation of a public option or public access points through such mechanisms as Postal Service banking or individual business and individual Fed accounts.

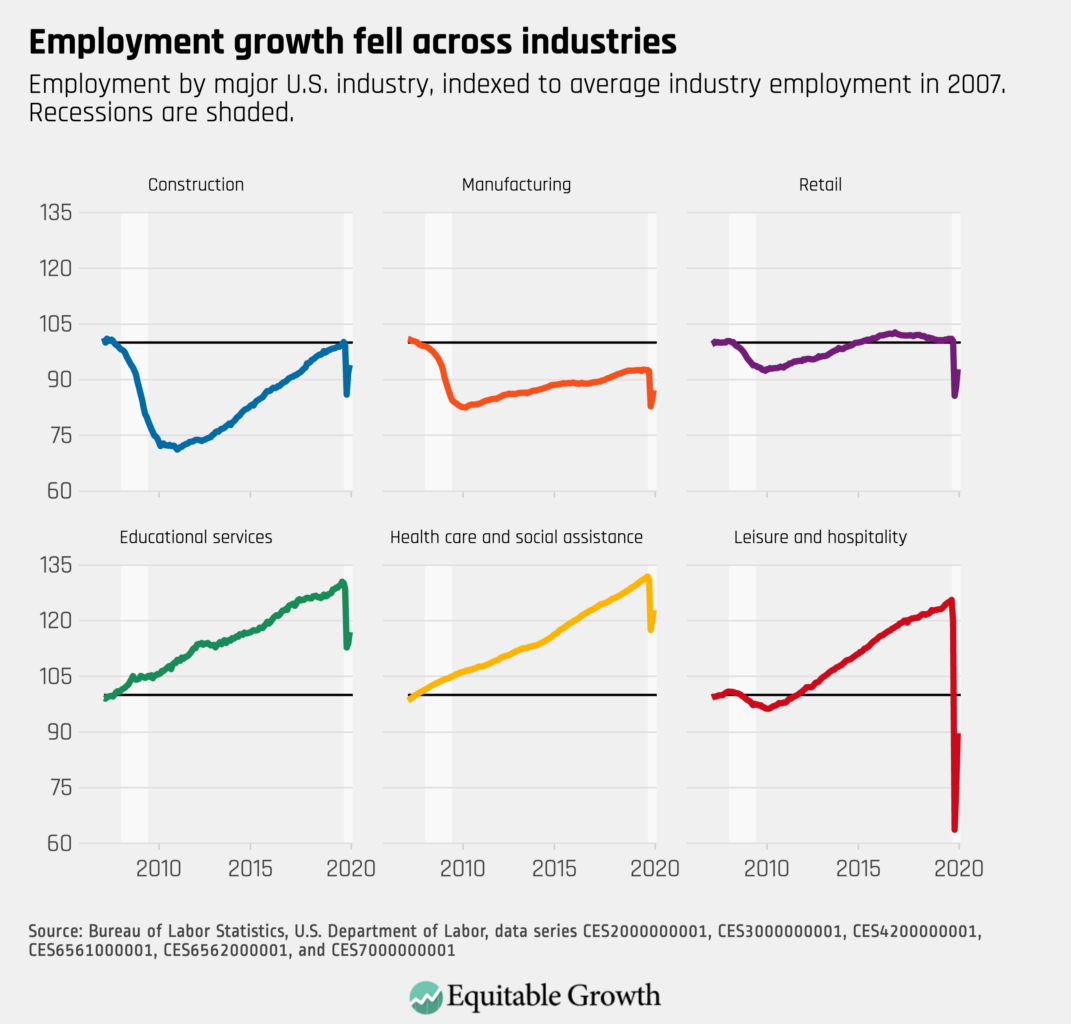

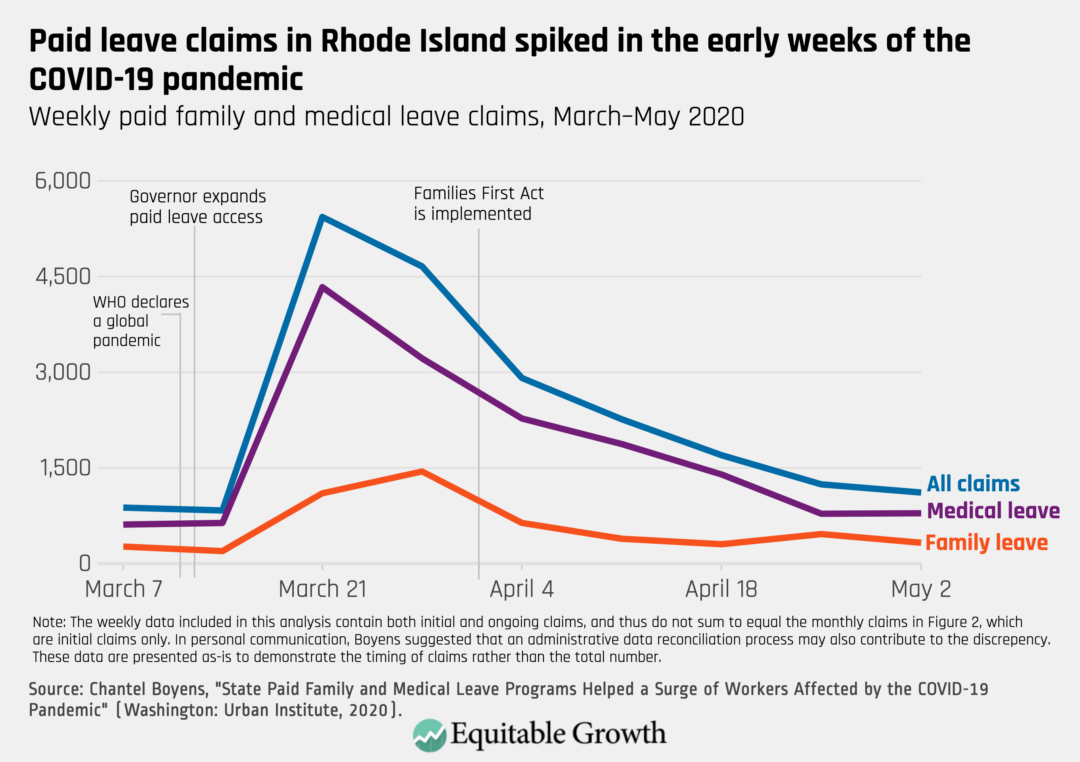

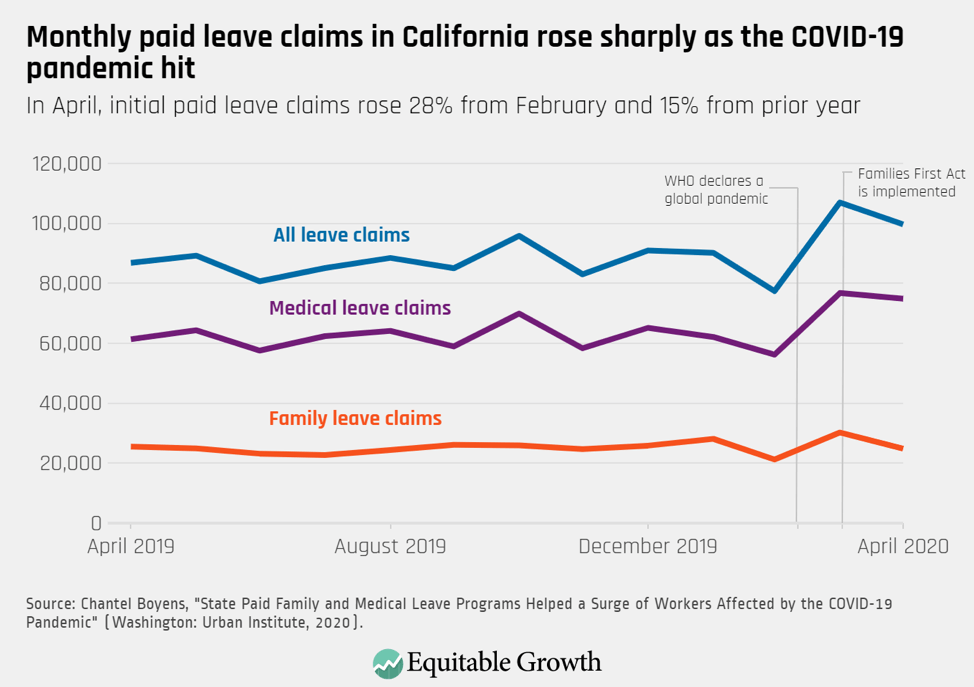

The second panel discussed ideas for building power for workers and families. It addressed a series of important economic and social issues that existed well before the coronavirus pandemic hit and have been exacerbated by its costly and deadly spread. As moderator David Mitchell, Equitable Growth’s director of government and external relations, put it, “The coronavirus recession did not create the problems that we are going to discuss today, but it has crystallized them.”

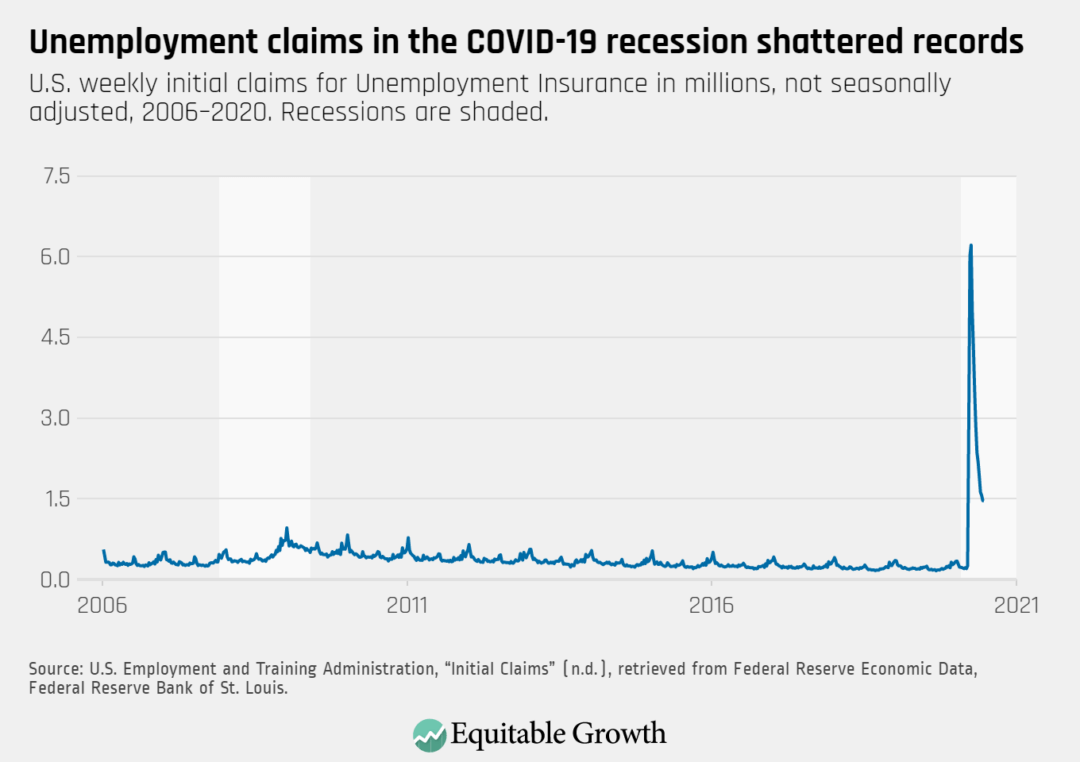

Naomi Zewde, an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy at the City University of New York, discussed how the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated health inequality. Even before the virus, she said, “You’re born in the wrong neighborhood, you go to the wrong schools, you’re likely to get a job that does not offer health insurance, and you’re more likely to die prematurely … the virus exposes some of the challenges with having this patchwork system of coverage, and it also exposes some of the challenges of having coverage tied to employment when you have an employment crisis,” she said.

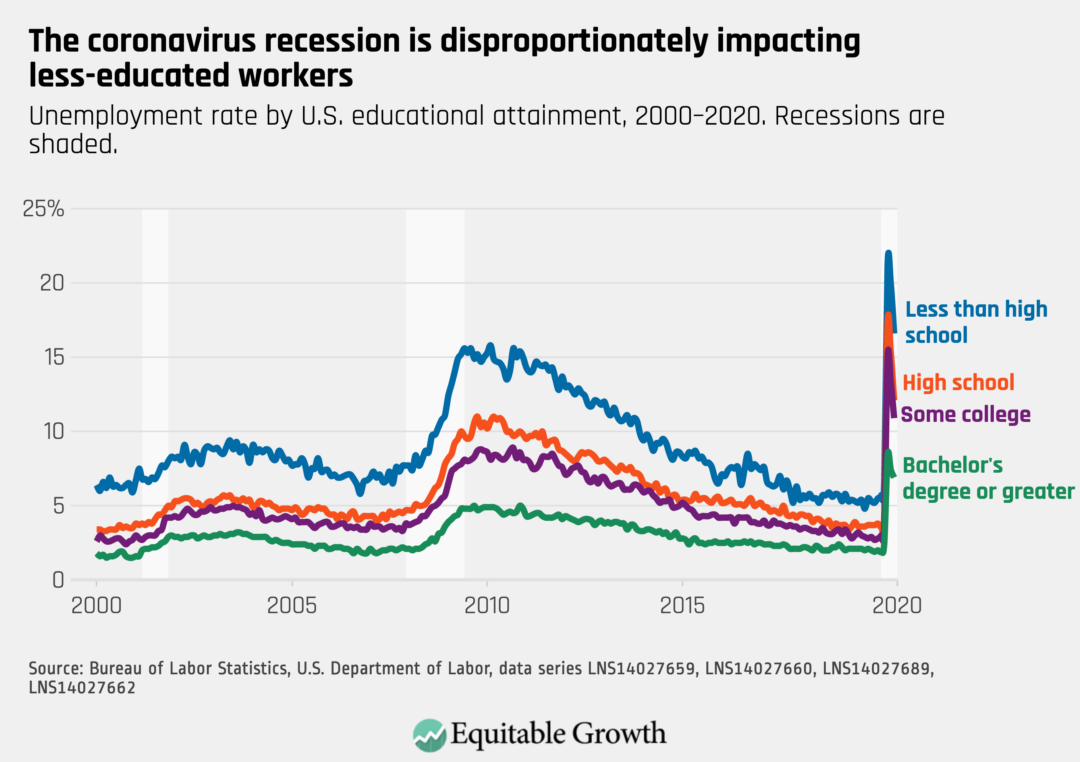

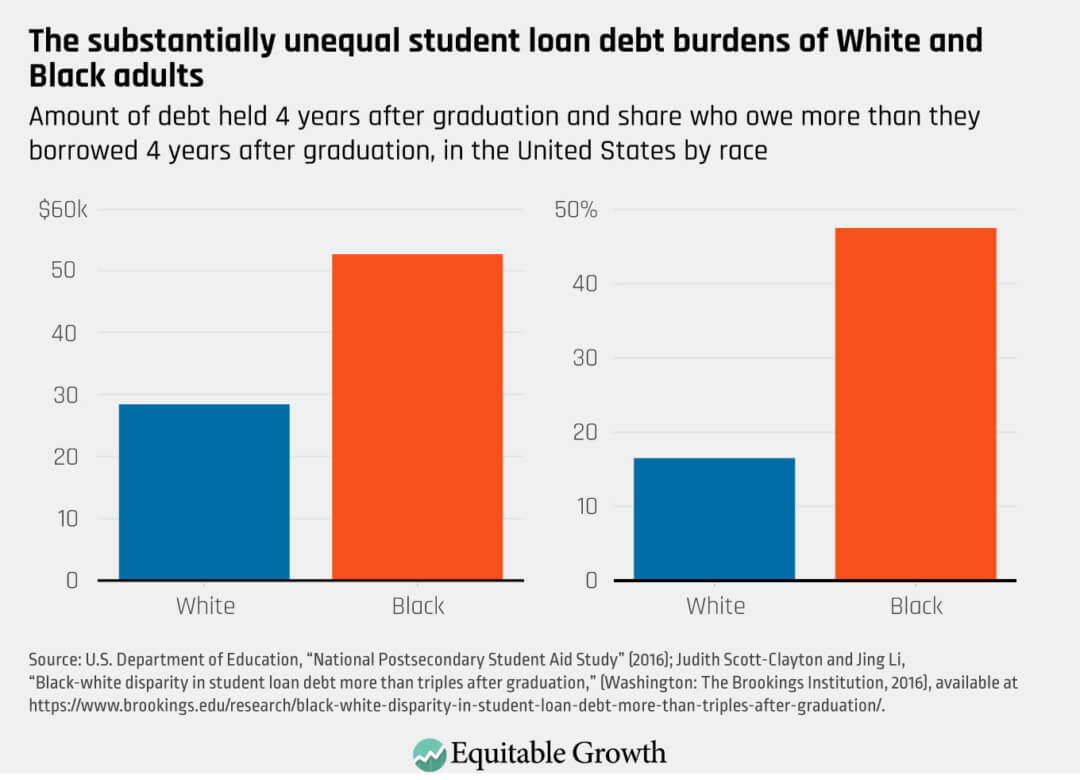

Discussing the Black Lives Matter protests, Zewde focused on the extraordinary racial wealth divide and the intense concentration of wealth at the very top of the income distribution—the “white billionaire class.” This concentration of wealth at the top, she said, leads to institutions and rules favoring that group over others, which contributes to the “violence of the state” that primarily affects vulnerable young Black people. And, she noted, they are facing the second recession in a decade, with increasingly bleak labor market prospects, as well as “the greatest educational debt burden of any cohort of Americans.”

She described the proposal she and Darrick Hamilton of The Ohio State University have advanced to cancel all federal student loan debt, which they have asserted is not only a long-term plan but also one specifically helpful in addressing today’s crises. “Instead of punishing people for seeking higher education and social mobility, find a way to reward it … so we can have a globally competitive workforce, on par with other countries that enable people to seek whatever education they want to without coming out with this huge albatross around their necks.”

Taryn Morrissey, an associate professor of public policy in the School of Public Affairs at American University, spoke to another long-term crisis exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic: the lack of access to quality, affordable childcare and early childhood education.

Morrissey pointed out that the costs of childcare have been twice the rate of inflation over the past two decades, and low-income families pay, on average, 35 percent of their incomes on childcare. And which children get what kind of care varies with age and income.

Before the pandemic, she said, “children in low-income households and infants and toddlers were much less likely to be in center-based care or in regulated or licensed care more generally … and this is a problem because on average, center-based care tends to provide higher-quality and more stable and reliable care than unregulated types of care.”

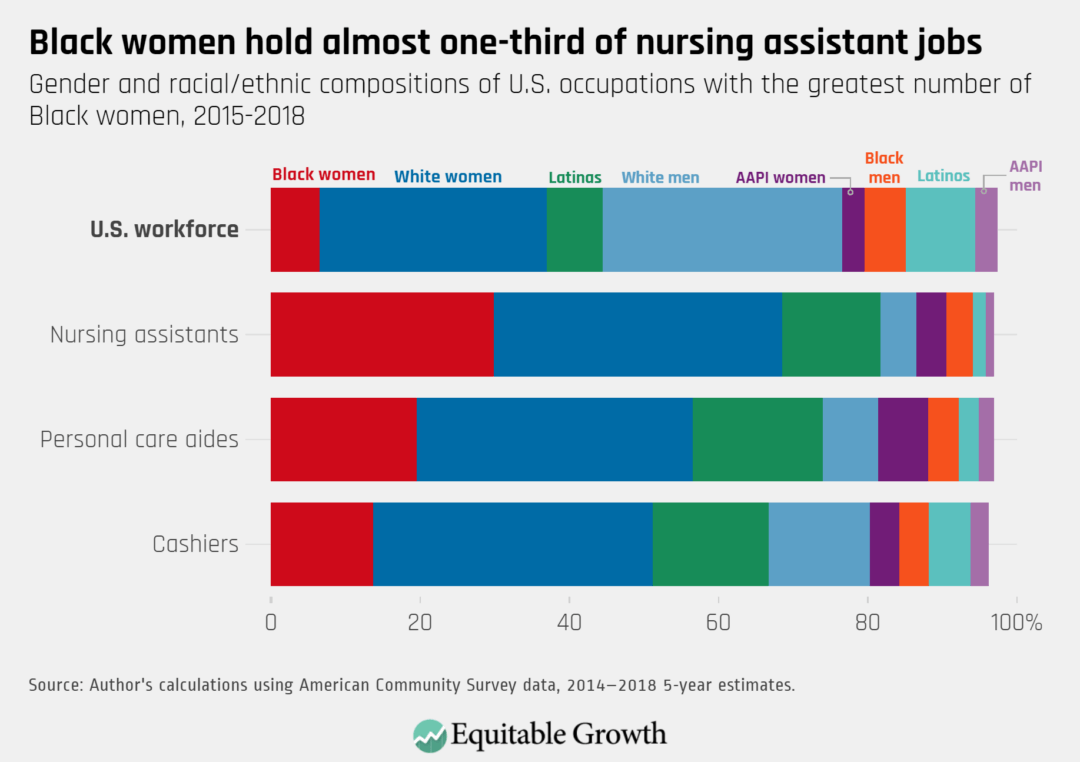

These disparities, she said, are due to lack of supply, high costs, and the general lack of public investment, particularly for children under age 3. Despite the high costs and despite what we know about the importance of early childhood education, she said, early care and early childhood education workers are paid little. And workers of color make even less than the average.

COVID-19, she said “puts all these problems in stark relief.” Many providers won’t survive months without adequate revenues. It is projected that as many as 4.5 million slots in licensed childcare facilities could be lost.

“Without swift and effective policy interventions,” she said, “there will be widespread shortages of childcare, and what remains will be very expensive and out of reach.” This, she added, will have an enormous impact on children’s learning and development. Moreover, if, as a result, working mothers drop out of the workforce, it could set them back decades. And, she said, all this will reinforce inequality.

To deal with the current crisis, Morrissey pointed to the need for short-term relief to keep existing childcare programs afloat. And she called for greater support for childcare and early childhood education workers. She said the Childcare Is Essential Act could accomplish these goals. To address long-term structural problems, she encouraged greater investment in Head Start and other early childhood education programs.

Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, an associate professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University, said that the coronavirus pandemic presents new strains on the workplace while exacerbating existing ones.

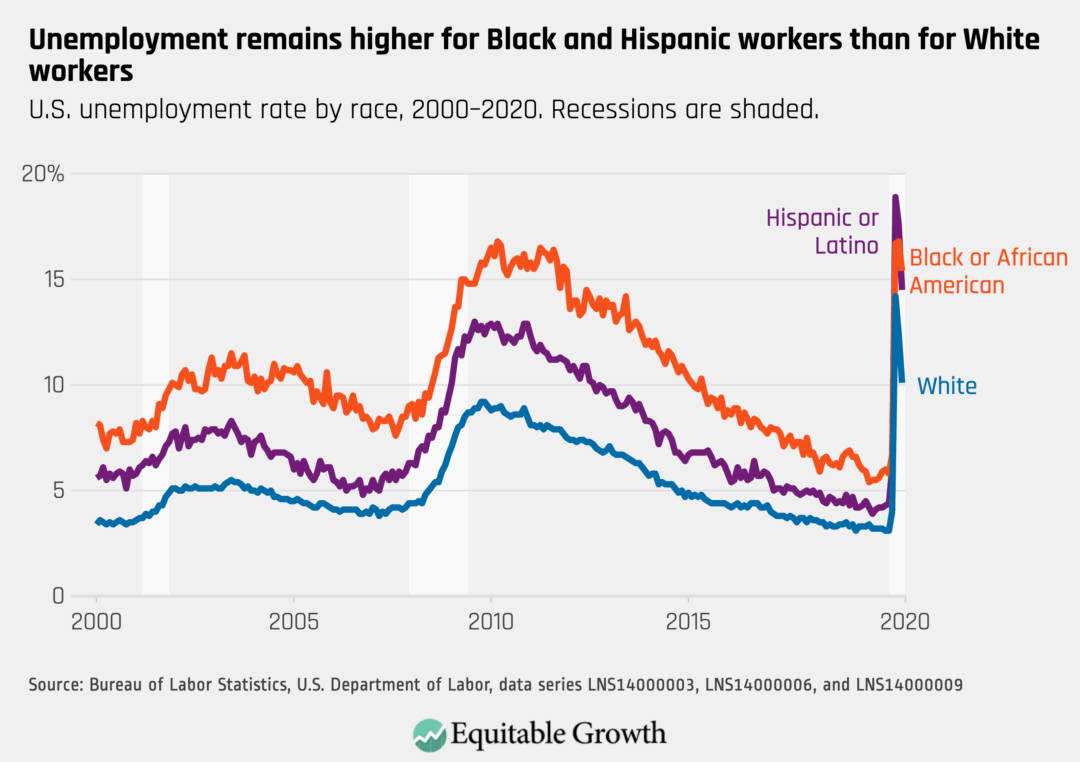

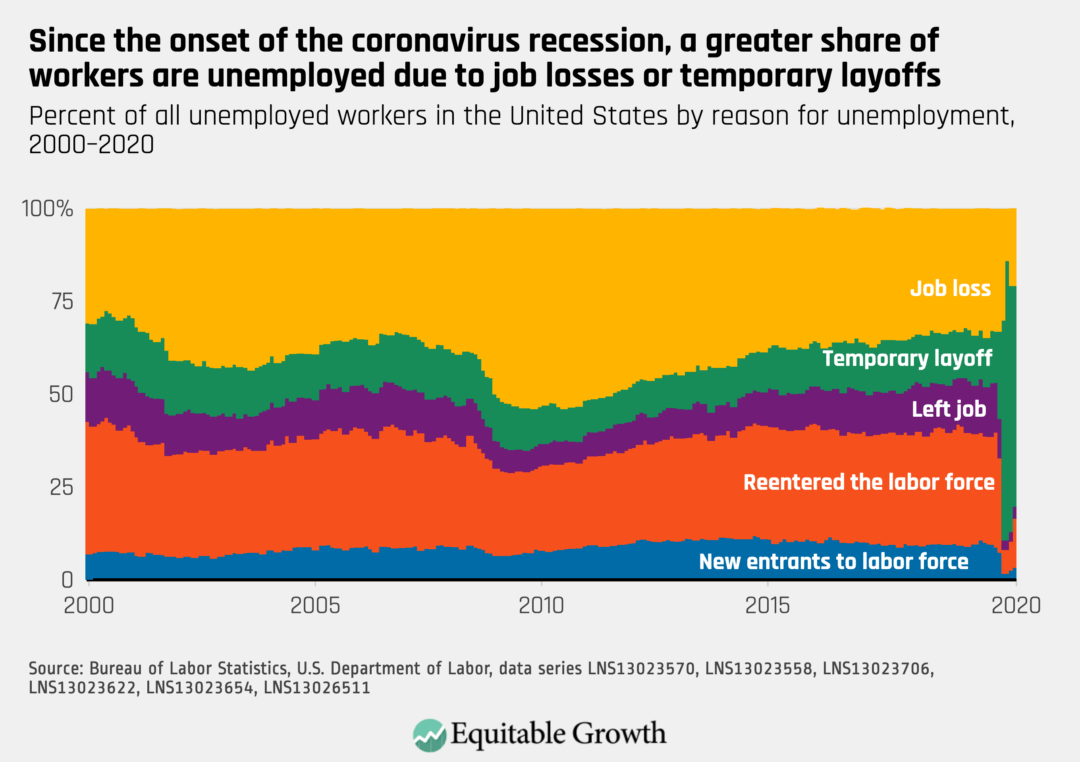

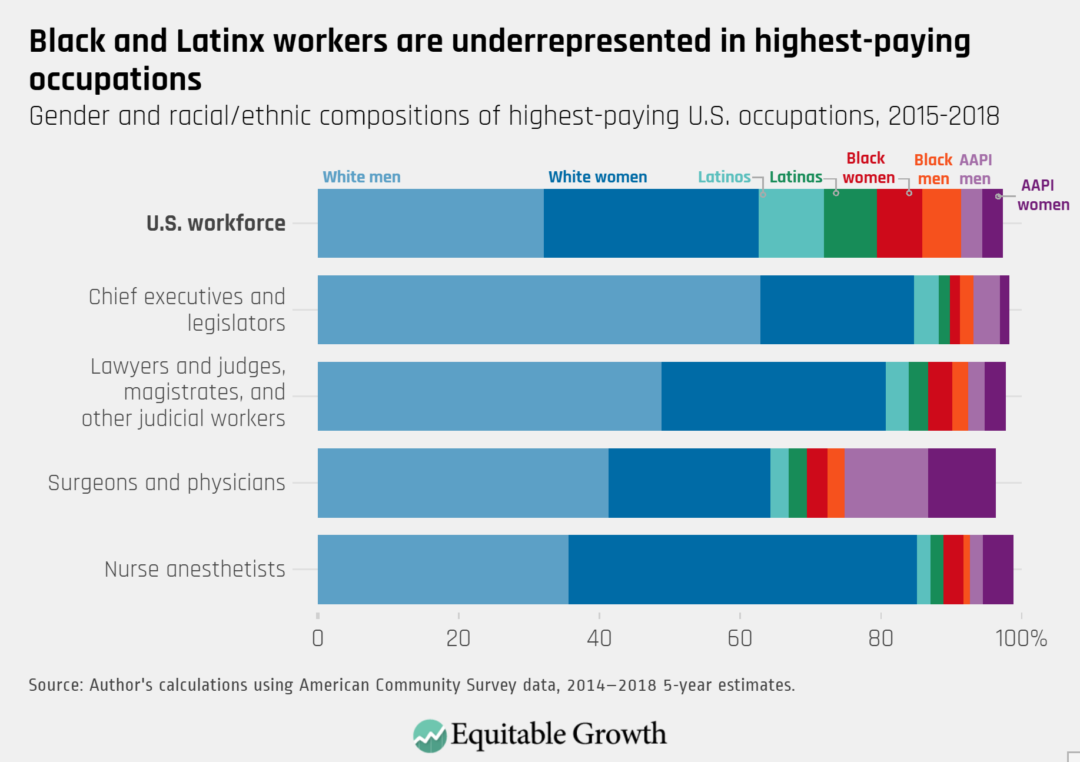

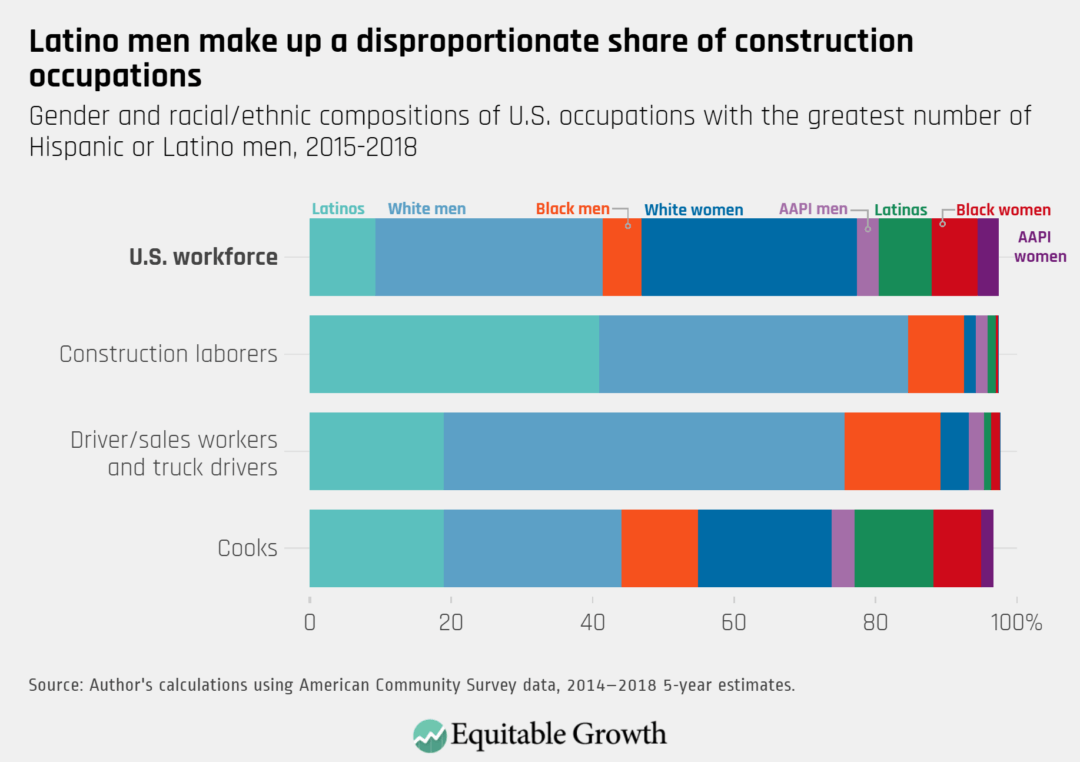

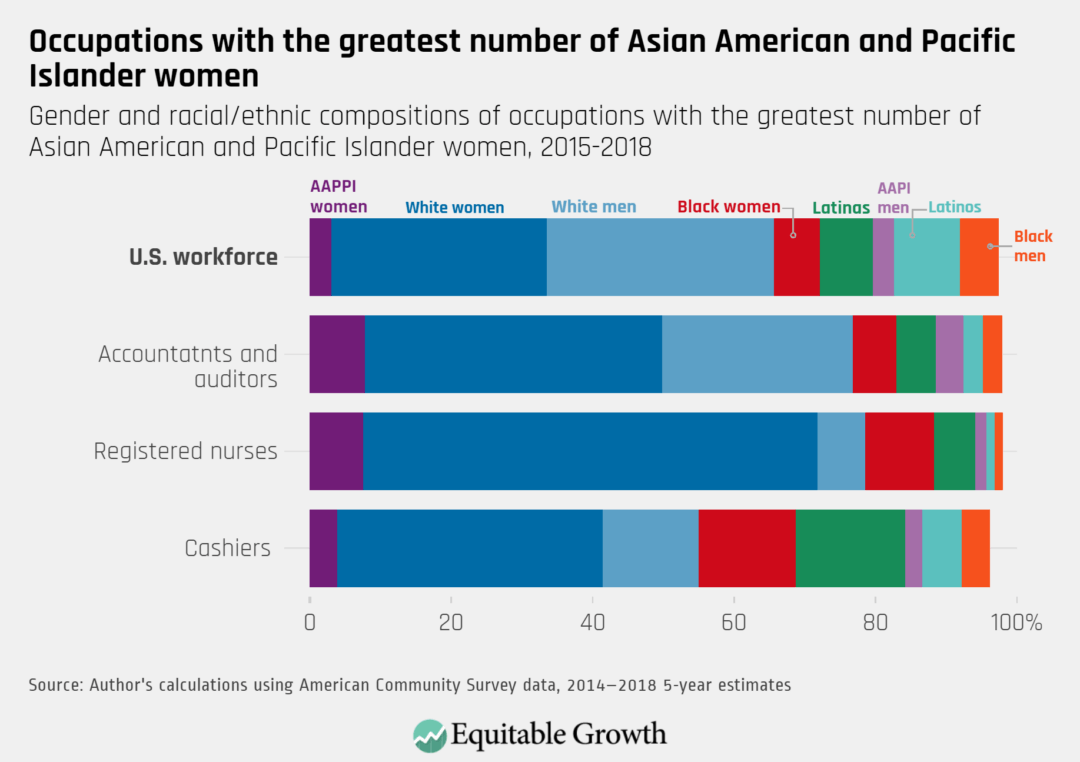

He pointed to the current health risk faced by those who have to work and interact with the public and the employment crisis created by the economic downturn, both of which have been borne disproportionately by Black and Latinx workers.

He cited an additional crisis, “the crisis of workplace voice.” This is “the ability of workers to weigh in on decisions that are important to them on an everyday basis at their jobs—how much they get paid, their benefits, the terms of their advancement, how they’re treated by their managers, and the health and safety conditions that they work under.”

Previous research, he said, shows that nearly two-thirds of workers have less say than they want over wages, benefits, and terms of advancement; nearly one-half of workers say they have little or no say in health and safety measures at their workplaces; and nearly half of all workers who are not union members would join a union if one were available to them.

With other colleagues, he surveyed essential workers in late April and early May on several coronavirus-specific issues related to conditions and worker voice. The questions related to use of personal protective equipment, availability of paid sick days, COVID-19 testing, and having a place and time to discuss workplace safety issues with colleagues. Union members were substantially more likely to give positive answers to each of the questions, by anywhere from 16 percentage points to 30 percentage points. This should not be a surprise, Hertel-Fernandez said, “because we know that this is a central function of unions—to provide these kinds of resources that workers need and want at their jobs.”

He added, “To the extent that worker voice helps workers get the kind of conditions that they need and want, it needs to be part of the public health response that states and cities are engaged in.” He cited policies that could enhance worker voice in this crisis and beyond, including electing workplace safety officers to ensure that workers are aware of their rights to a healthy and safe workplace, establishing worker-manager committees to ensure workers have a say in reopening conditions, and ensuring that workers can form unions and hold their employers accountable by going on strike.

The Equitable Growth Vision 2020 project includes a book of 21 policy essays that could form the basis of an agenda for equitable growth in the coming decades. Four Vision 2020 essay authors were featured at last week’s event. Though we at Equitable Growth could not have anticipated the pandemic and resulting recession when we published the book in February, the ideas showcased—geared at achieving structural economic changes—are even more urgently needed today.

For a complete video of “Vision 2020: Focusing on economic recovery and structural change,” click here.