The United States is the only advanced economy in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that does not guarantee any paid family and medical leave to its entire workforce. Though 10 U.S. states and localities have currently implemented or have begun to implement programs for their residents, there is no nationwide paid family and medical leave plan that covers all workers across the country regardless of where they live or work.

As a result of this policy choice, U.S. workers, their families, and their employers often lack the resources and support they need during a family transition or health shock, including the arrival of a new child, an aging parent, a diagnosis of an illness, and personal injuries. When paid leave from work to deal with and adjust to these moments is needed but not available, workers are forced to choose between their responsibilities at home and earning a paycheck, which can have far-reaching implications for families, employers, and the broader economy.

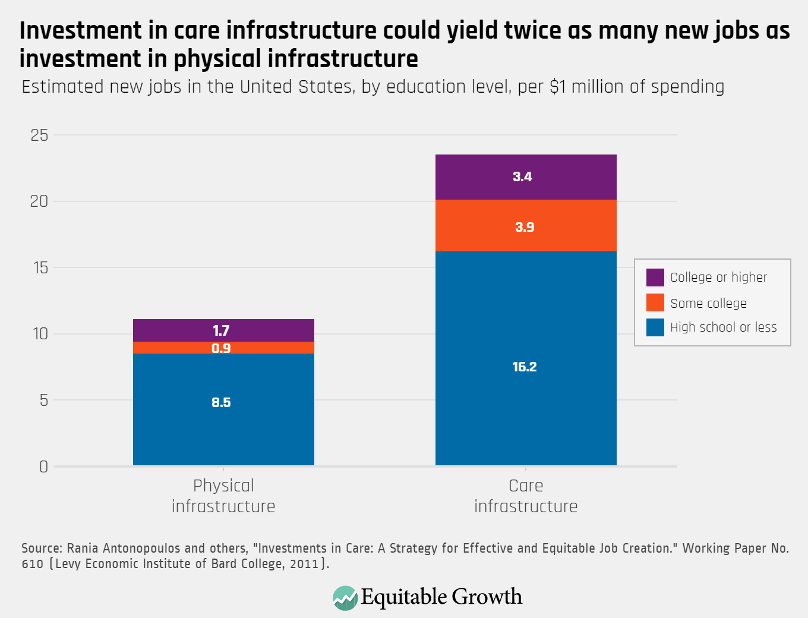

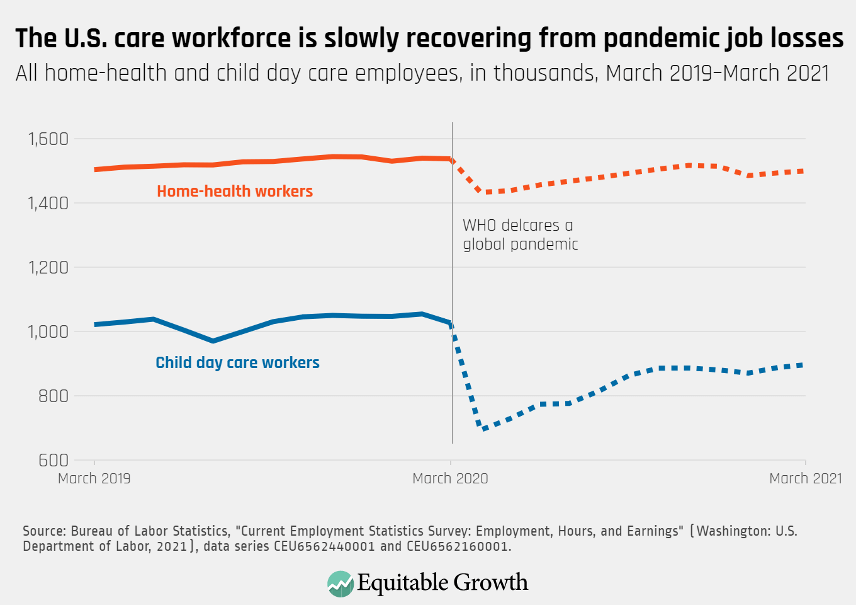

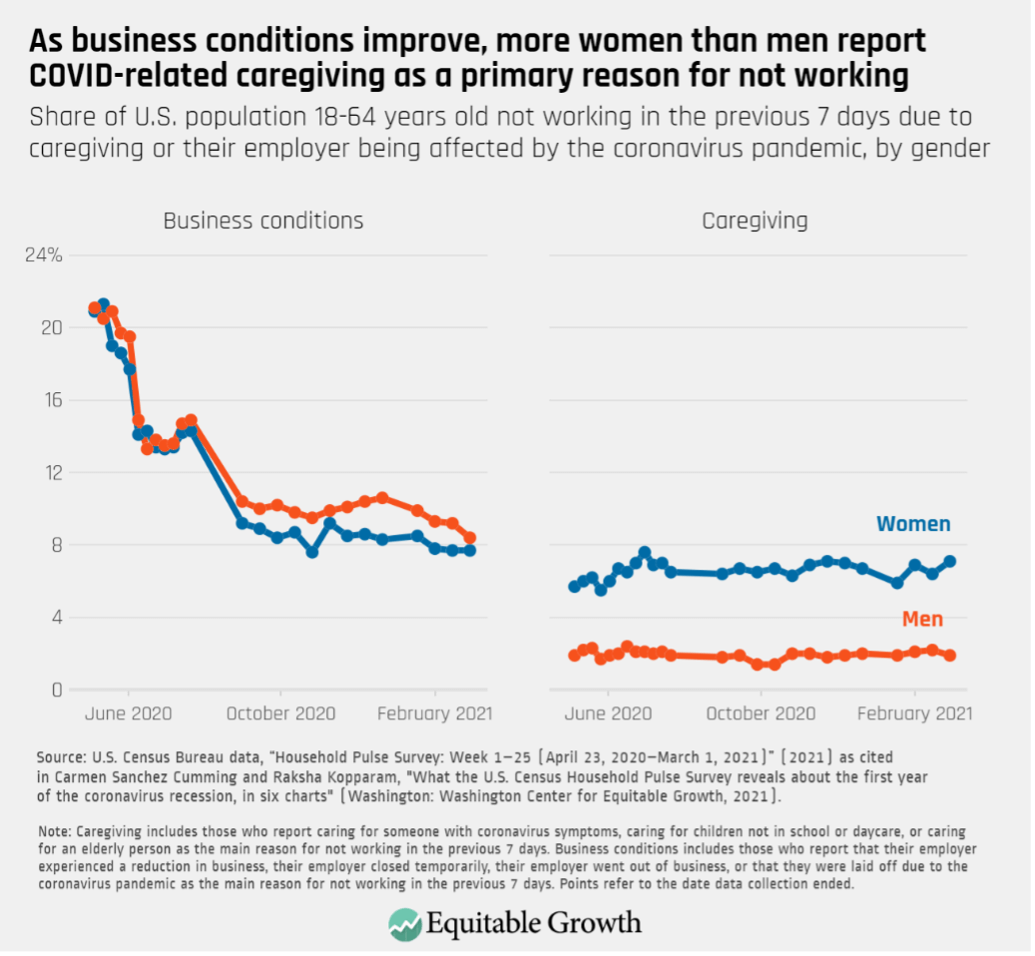

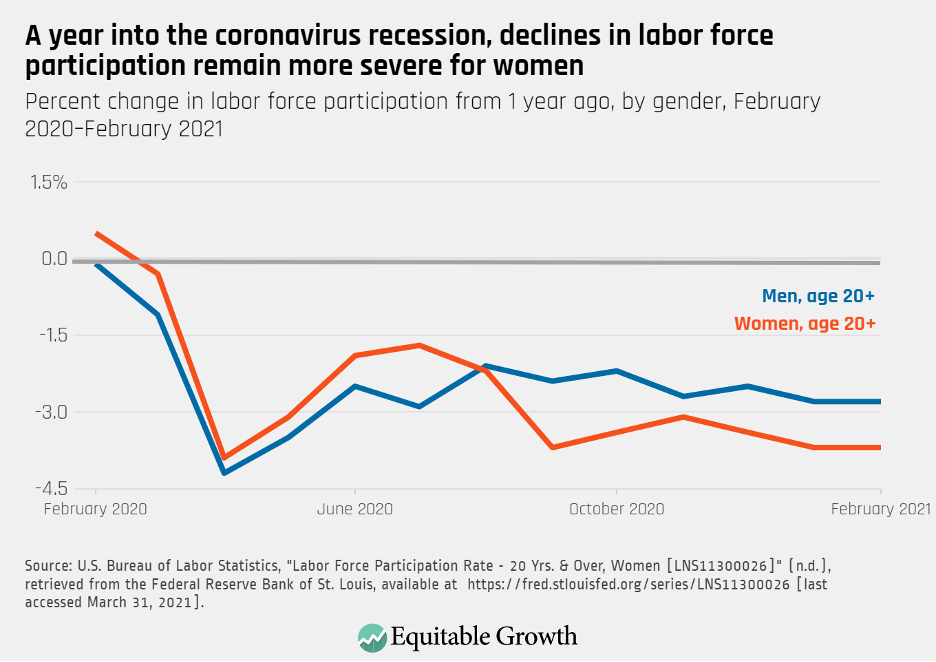

The coronavirus pandemic and recession exacerbated these longstanding caregiving and work-life conflicts for U.S. workers. As the nation emerges from the greatest health, economic, and caregiving crises in a generation, though, policymakers preparing for the post-pandemic economy are proposing investments in U.S. physical and caregiving infrastructure—including paid family and medical leave, child care, and home-based health services. Inequities in the recovery from the coronavirus recession point to the importance of these investments. In March 2021, for instance, U.S. women’s labor force participation rate was 56.1 percent, a 33-year low, and women of color have been hit the hardest.

Meanwhile, emerging research confirms what many families already knew: Caregiving responsibilities are a significant driver of women’s exit from the labor force. Investing in U.S. care infrastructure will help ensure women can reenter, stay, and thrive in workplaces; that work and caregiving responsibilities are more equitably distributed; and that the country is equipped to handle both national crises, such as a new pandemic, and the personal crises that too often leave workers and their families in economic peril.

This factsheet looks at research on—and lessons learned from—state-provided paid family and medical leave programs in the United States. Building on this evidence and these lessons in establishing a national paid leave guarantee would address one of the most pressing deficiencies in the nation’s caregiving infrastructure.

Paid leave programs increase labor force participation, particularly among women

- Evidence indicates that under California’s paid leave law, new mothers are estimated to be 18 percentage points more likely to be working a year after the birth of their child. During the second year of their children’s lives, mothers’ work hours increase by 18 percent, and their weeks at work increase by 11 percent, relative to their peers prior to the implementation of the state’s paid parental leave policy.1

- Recent research corroborates these findings, indicating that in California, mothers with access to paid leave demonstrate an approximately 20 percent increase in the probability of labor force participation during the year of their child’s birth. This increase remains significant up to 5 years later.2

- Research using administrative data in California and New Jersey finds that paid parental leave in both of these states is associated with increased labor force participation for women around the time of birth, and this finding is driven nearly exclusively by the increased labor force attachment of less-educated women.3

- Research analyzing women’s labor force participation for different cohorts also suggests those on paid leave have higher employment rates after pregnancy, compared to those who do not have paid leave. Those on paid leave have a participation rate of 82 percent after 10 years—considerably higher than those who quit their job during pregnancy, who have a 64 percent participation rate after 10 years.4

- Though much of the public conversation has focused on paid leave to care for a new child, paid leave to care for one’s own serious medical condition and paid leave to care for a noninfant family member with a serious medical condition are also important components of the program. Specifically:

- A synthesis of related research suggests that paid medical leave could reduce household income volatility, facilitate reemployment, improve business productivity by reducing presenteeism—that is, the act of attending work while sick—and increase labor supply.5

- Research from California finds that following the introduction of California’s paid leave law, the labor force participation of unpaid caregivers increased from 66 percent to 73 percent, in comparison to a smaller increase (68 percent to 70 percent) in other states. Additionally, while the percentage of unpaid caregivers engaged in part-time work fellover this time period in other states, it nearly doubled in California, rising from 10 percent to 19 percent.6

Paid leave to care for a child improves child well-being and strengthens the human capital of the next generation

- In studying the mental and physical health outcomes of elementary school students exposed to paid leave in California, researchers find lower rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obesity, ear infections, and hearing problems. These benefits are most apparent in children from families with lower socioeconomic status, which is consistent with the theory that paid leave provides additional benefits for those families that previously could not take leave due to access or affordability concerns.7

- Following the implementation of paid leave in California, researchers saw a significant reduction in hospital admissions for pediatric abusive head trauma, indicating that paid leave decreases rates of child abuse and maltreatment.8

- Paid leave also may allow for more bonding between parents and their child. In fact, state paid leave policies are shown to increase rates of breastfeeding, a parenting activity with a strong, evidence-based link to long- and short-term health benefits for babies.9

- Recent work finds that paid family leave also increases the amount of time mothers spend in child care activities, including reading, talking, homework help, and other activities that are important for children’s human capital development.10

- One study that examined paid leave in California finds that mothers earn less and are less likely to work under the program, though there are questions about the study’s generalizability. Still, the researchers also find that first-time mothers who took up paid leave in response to the policy change spent more time reading to their children, taking them on outings, and eating breakfast as a family, compared to similar mothers not exposed to the paid leave policy change. If this finding holds, it complements the larger body of work on the human capital benefits of paid leave to care for a new child, and suggests that paid leave should be coupled with additional care infrastructure, such as an effective and affordable child care system, to allow families to both parent intensively and prosper financially.11

Paid leave programs protect workers from health and economic shocks

- Family incomes generally dip substantially around the birth of a new child,12 but research shows that the introduction of California’s paid leave program was tied to a 10.2 percent decrease in the risk of families with new children dipping below the poverty threshold.13

- Time off to deal with one’s own serious medical condition is associated with better health outcomes. Having access to paid sick leave is associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality across a wide range of conditions, including heart disease and unintentional injuries.14

- Administrative data from California and Rhode Island show that state paid leave programs were responsive to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with rates of claims between February 2020 and March 2020 increasing 43 percent in California and 300 percent in Rhode Island.15

Paid leave is an important support for small businesses

- While some might argue that guaranteed paid leave for workers creates burdens for businesses, analysis of California administrative data finds no evidence that employee turnover at firms increases or that wage costs rise when paid leave-taking occurs.16

- Research on employers in Rhode Island similarly finds limited effects of the state paid leave policy on businesses, with employers noting few significant impacts on business productivity and related metrics.17

- Survey research finds that 63 percent of small- to medium-sized employers in New Jersey and New York report that they support or strongly support paid family and medical leave programs.18

- In a 2010 survey of 253 California employers on the state’s paid family and medical leave program, a large majority said the law has “no noticeable effect” or a “positive effect” on productivity (88.5 percent), profitability (91 percent), turnover (92.8 percent), and morale (98.6 percent).19

- New research shows that the introduction of paid leave in New York both improved employer’s reports of how easy it was to accommodate employee absences and increased rates of leave-taking among employees. In the 3 years following implementation of the program, a majority of businesses support the program, while a small minority—less than 10 percent—say they are opposed.20

Paid leave boosts macroeconomic growth

- In concert with other care infrastructure policies, paid leave could help raise the labor force participation rate of U.S. women to be comparable with the rate for women in peer nations, which could increase Gross Domestic Product by as much as 5 percent.21

- McKinsey analysts estimate that implementing policies such as paid leave that advance gender equality prior to the pandemic’s end could add $2.4 trillion to U.S. GDP and create near gender parity in the U.S. labor force by 2030.22

Paid leave is a sustainable investment in the vibrancy of our economy

- While some critics argue that a federal paid leave program is too expensive, a recent policy analysis concludes that the Biden administration and Congress could enact a new self-financed paid leave program without increasing overall average taxes for workers earning less than $400,000 a year.23

- By allowing family members to provide care, paid leave may also result in budgetary savings for government programs. One study finds that California’s paid leave program is associated with an 11 percent decline in nursing home usage among older adults, which is associated with substantial decreases in Medicare and Medicaid spending.24

Conclusion

This factsheet presents some of the research and evidence on paid family and medical leave as it relates to families’ economic security, human capital development, employer experiences, and U.S. economic growth. For more information on specific paid leave provisions or other aspects of the care economy, see Equitable Growth’s other factsheets on paid caregiving leave, paid medical leave, paid leave policy design, and our most recent factsheet on care infrastructure investments more broadly.