Overview

There is an obviously urgent and irrefutable need for social distancing today across the breadth of the United States during the new coronavirus pandemic. The sacrifices necessary amid this public health emergency, however, impact some workers and their families and business owners and their families more than others. The U.S. restaurant industry is perhaps the most apt case in point.

Many cities and states took a decisive step to curb the spread of the coronavirus by ordering bars, restaurants, and social gatherings, such as weddings and other celebrations often hosted or catered by restaurants, to shutter. There is early evidence that the cities that took this step at the outset are finding success in “flattening the curve” of the outbreak. Closing restaurants and encouraging people to stay home is saving lives, yet millions of workers and owners in the restaurant industry are sacrificing their livelihoods. For those few restaurants and staff still serving food and drink through limited carry-out and delivery services, they are risking their health, too, and will be even more exposed to becoming infected with COVID-19, the disease with no cure spread by the new coronavirus, as governments in states and cities begin cautiously to allow sit-down service.

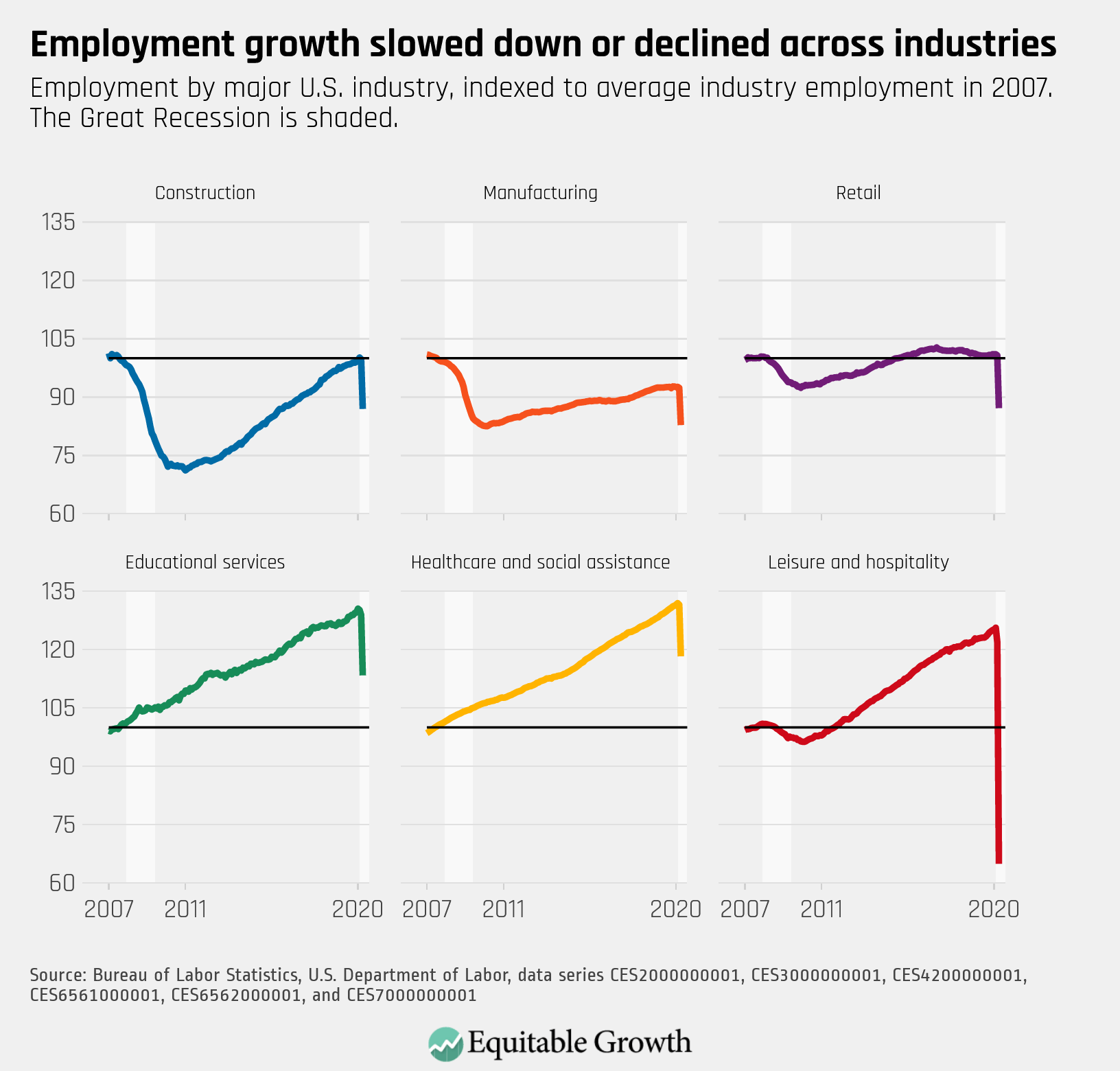

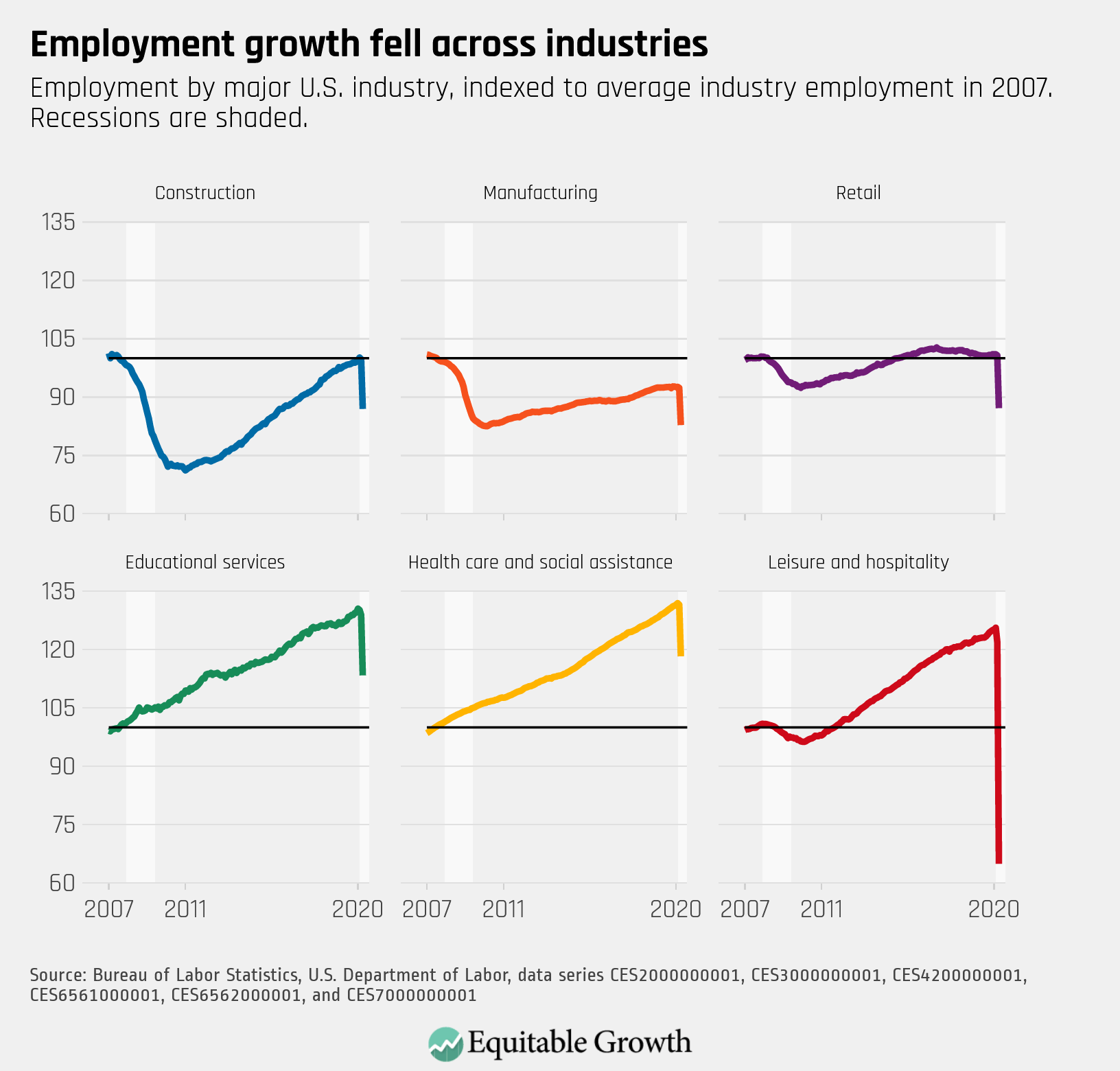

The restaurant industry had been one of the fastest-growing sectors of the U.S. economy, growing by 30.2 percent since the end of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, compared to 18.6 percent for the rest of the private-sector economy. This growth has occurred in nearly every region of the country, both urban and rural, which makes it unusual in that many other industries tend to grow in single or a few similar regions (think the high-tech sector) and benefit those regions exclusively. The restaurant industry’s total revenue in 2019 was $863 billion, representing 4 percent of our country’s Gross Domestic Product. It was projected to grow by $36 billion in 2020.

That was the case until the coronavirus pandemic hit the industry particularly hard.

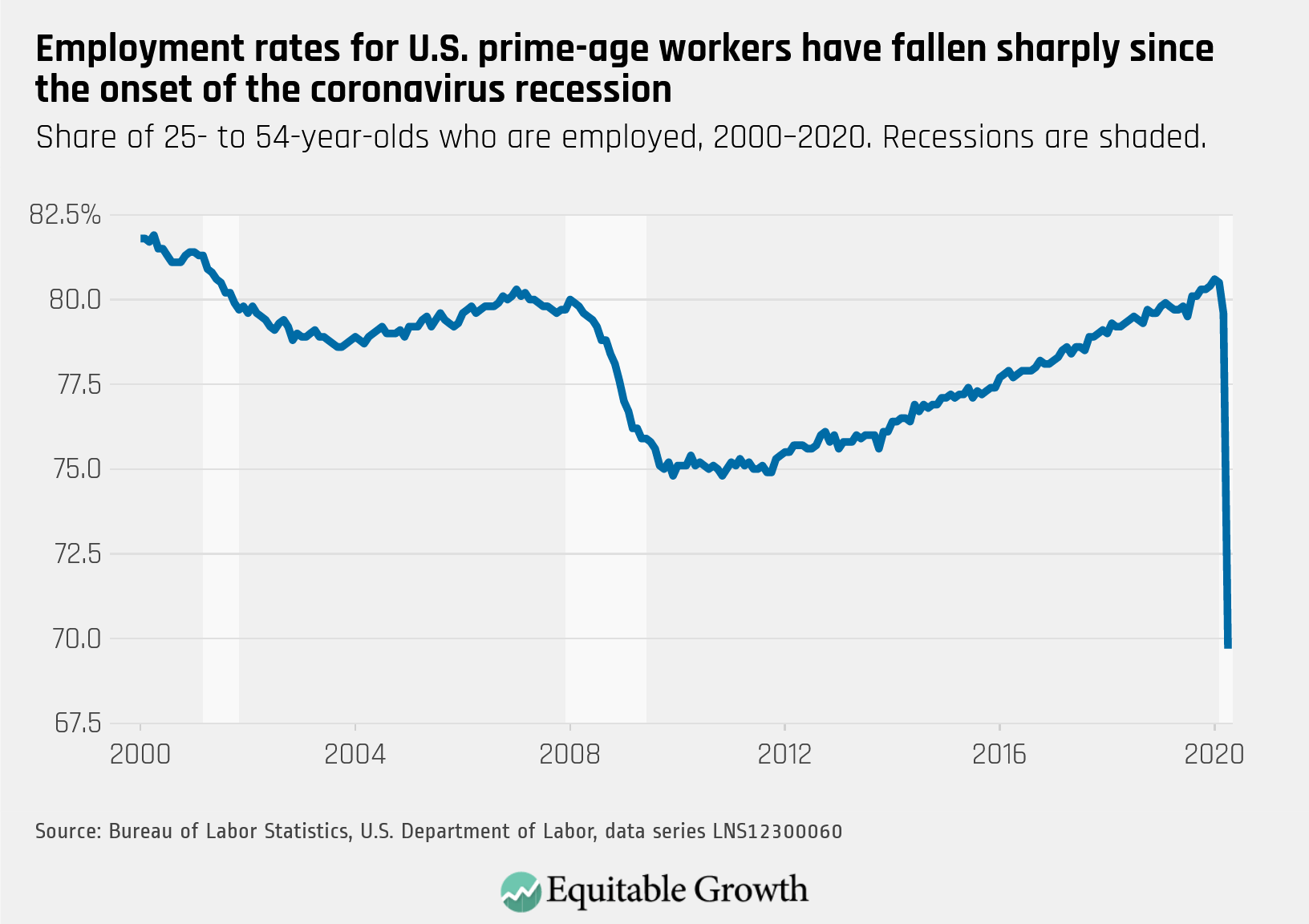

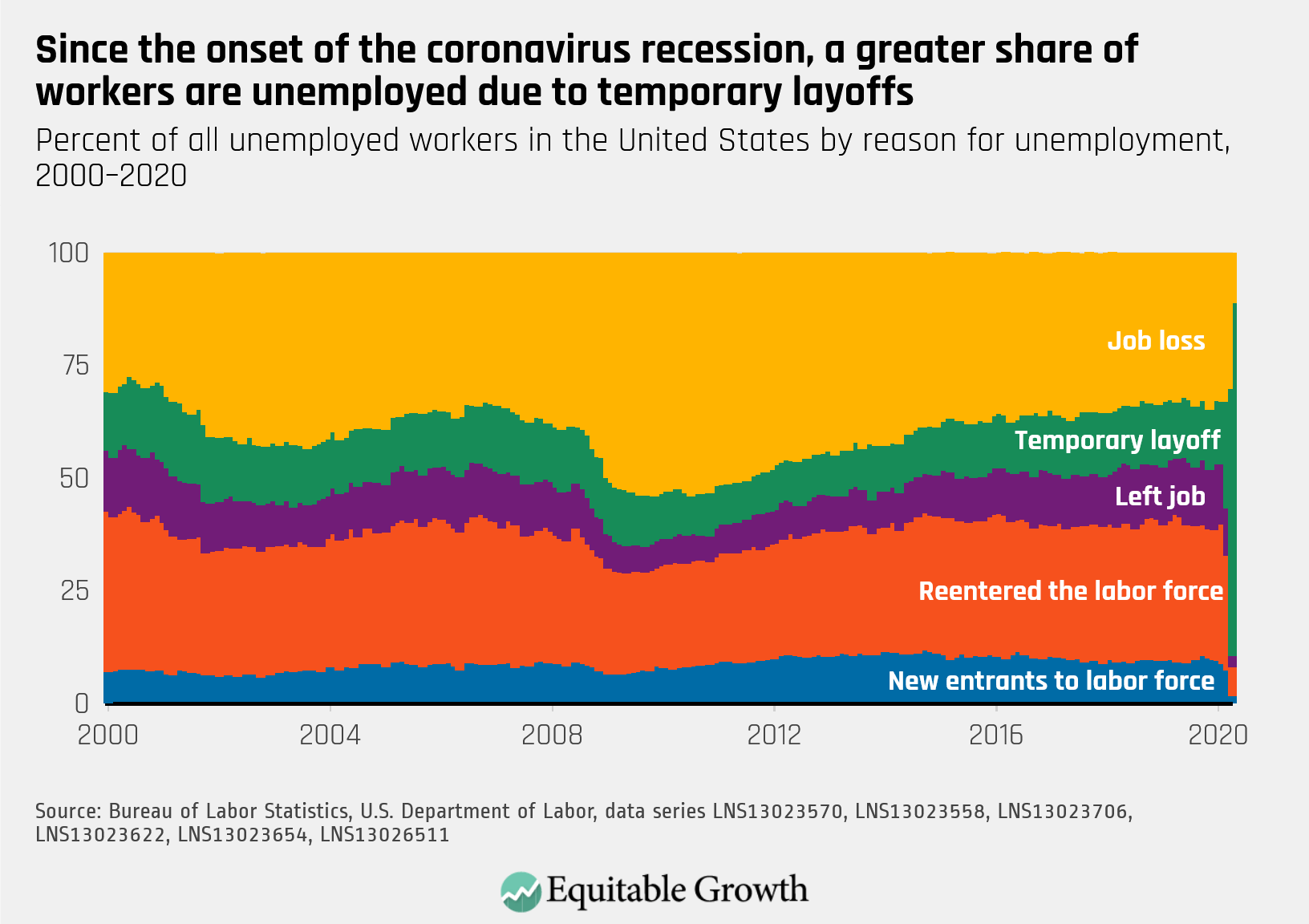

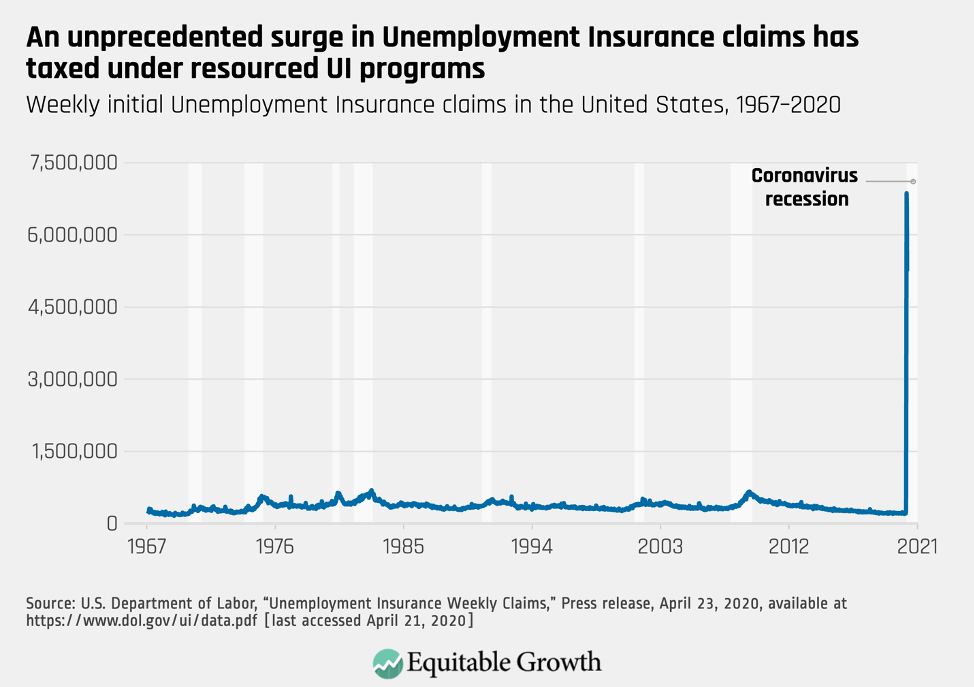

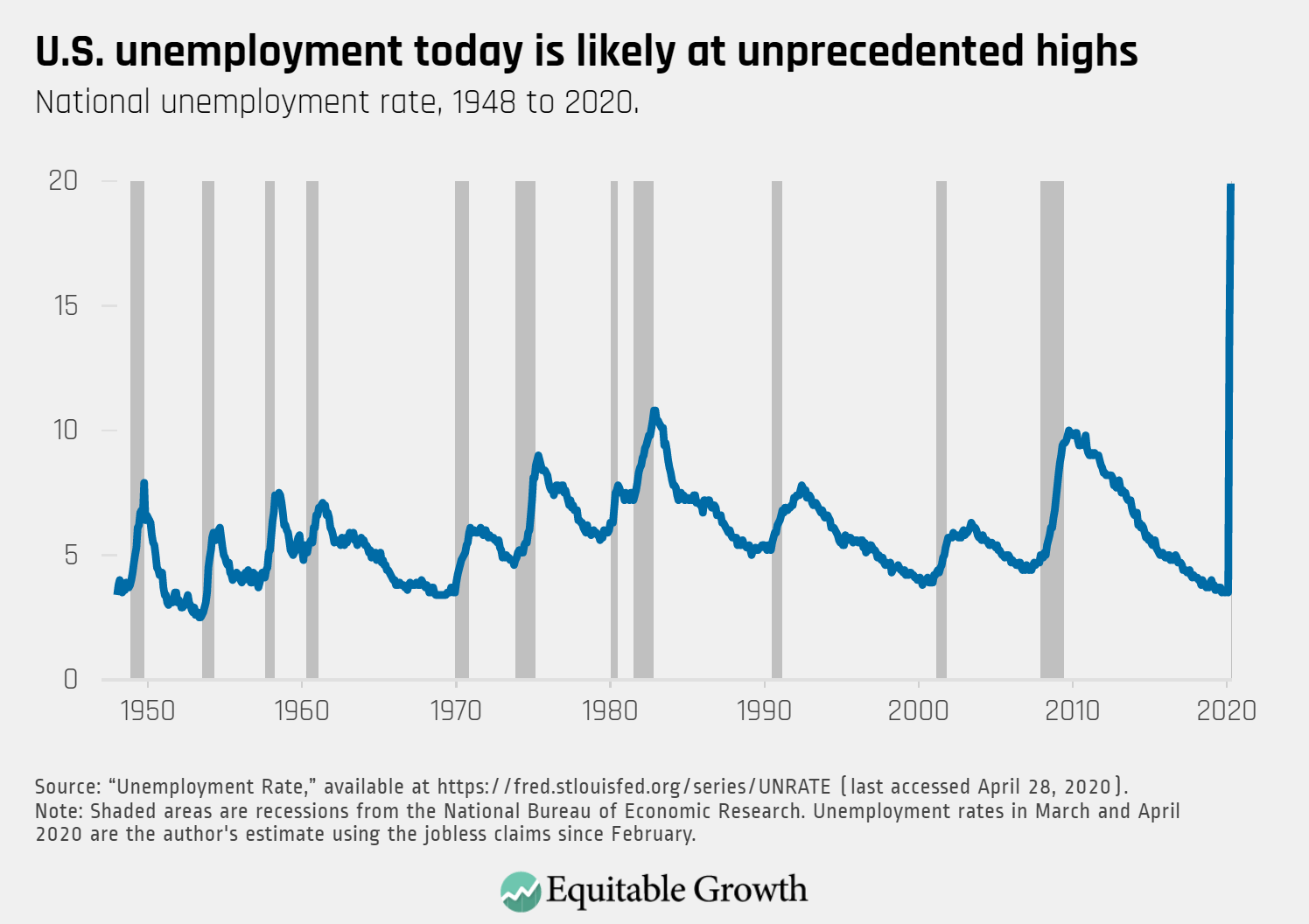

In just the first full month of the pandemic, in March 2020, the U.S. economy shed 714,000 private-sector jobs, 58.5 percent of which were concentrated in the restaurant industry alone (417,300 jobs lost). Final April data on job losses in the restaurant sector will not be available until early May, but the National Restaurant Association estimates that “more than 8 million restaurant employees have been laid off or furloughed since the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak in March,” or about two-thirds of all workers in the sector.

The industry consists mostly of small businesses. And the restaurant workforce, though large, is disproportionately composed of low-wage workers, thus finding ways to help restaurant workers maintain their jobs or reclaim them as the pandemic lessens its grip on the nation and the economy begins to recover will help mitigate income inequality. Restaurants, though, are very “high touch” services firms—factors that, all together, leave restaurant establishments and their workers almost uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus and COVID-19.

What’s more, restaurants are an important part of the fabric of economic life across the country. The restaurant industry consists of many kinds of businesses, from nationwide chains to regional chains to single metropolitan eatery chains to individually owned restaurants and bars. In the United States, the industry employs more than 11.8 million workers at more than 657,000 establishments. An estimated 5 million to 7 million chefs and line cooks, dishwashers, hosts, servers, bussers, and bartenders are predicted to lose their jobs during this pandemic. They work primarily at restaurants with less than 50 employees, according to the National Restaurant Association. And most of these restaurants are not chain establishments but individual establishments operated by single owners without dependable and quick access to savings or other financial streams to carry them through a prolonged or even a relatively short recession.

In late March, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, which provided more than $2 trillion to stimulate our national economy. It includes $349 billion for loans to small businesses backed by the U.S. Small Business Administration and processed by local and national lenders. Despite this historically high amount of financial relief, it was not enough—not by a longshot—to help the U.S. restaurant industry weather the sharp collapse of its revenues, enable its workers to remain in the workforce, and prepare both owners and workers to help power the economic recovery.

The Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program is out of funds as of mid-April, with “accommodation and food service borrowers” garnering only the fifth-highest amount of stimulus money despite its legions of small business proprietorships. Because the industry already laid off or reduced the hours of most of its workforce prior to the distribution of the stimulus funds from the CARES Act, the financial aid may well have come too late to save most U.S. restaurants or their workers’ jobs. The additional $380 billion in rescue funding for small businesses passed by Congress two weeks ago, with stipulations that the funding flow toward less-sizable small businesses, may help. But even this new funding is expected to disappear in days.

Will any future SBA loans be considered by Congress as the mostly small, independently owned restaurants contemplate their futures? This and other questions are unknowable at this point in the uncertain arc of the coronavirus recession. Yet policymakers and economists alike need to understand not only the evolving plight of the U.S. restaurant sector, but also the deep economic inequalities that underpinned the industry during its prepandemic boom times. This issue brief first details the profile of the restaurant workforce before the coronavirus recession to understand its mix of economic inequalities. The analysis then turns to the structure of the industry itself, highlighting its national scope and its mostly small business proprietorships.

This issue brief closes with three broad policy recommendations. As the U.S. restaurant sector struggles to find its footing amid the continuing menace of COVID-19 over the course of 2020 and into 2021, policymakers should:

- Ensure that any future stimulus funds or other federal support for the industry focus on giving priority to smaller businesses with fewer than 100 employees, which is the firm-size limit that best targets aid to restaurants and gives independently owned businesses a better chance

- Continue to support policies that require businesses to expand “high-road” employment practices to ensure the restaurant industry not only comes back, but also comes back in a way that is more equitable and sustainable

- Put in place pandemic economic resiliency plans that can reduce uncertainty in this crisis and better prepare for future public health emergencies that afflict this most “high touch” of high-tech services sectors

A sector so important to the economic and social lifeblood of our nation can help power an economic recovery swiftly and sustainably. But this will only happen if federal support ensures these mostly small businesses get a fair shake and their workers gain the workplace protections and more equitable wages they need to become more productive workers and more stable consumers amid the recession and into the economic recovery.

Download File

More resilient small U.S. restaurants and their workers can exit the coronavirus recession and sustain an equitable economic recovery

A profile of the restaurant workforce across the United States

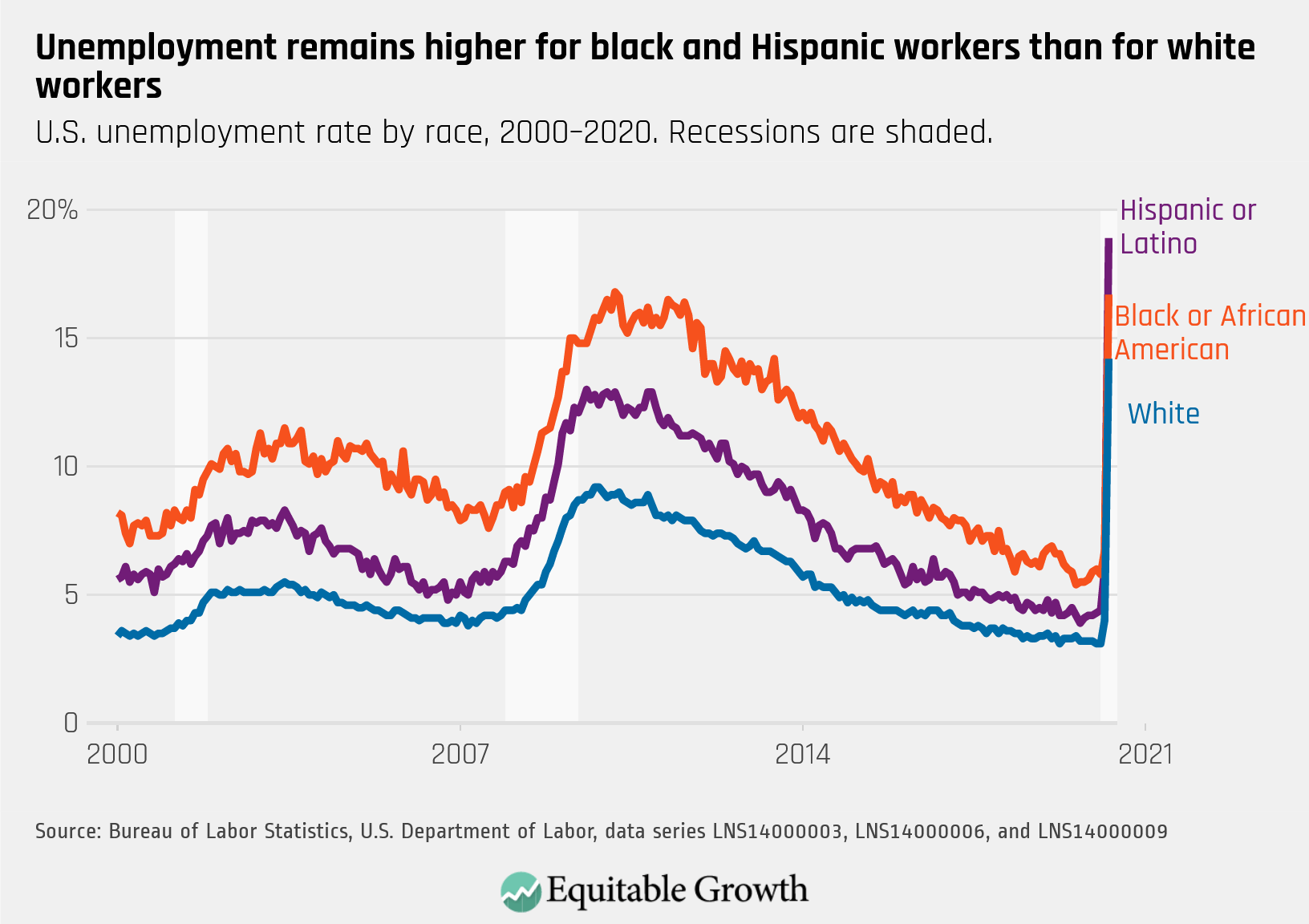

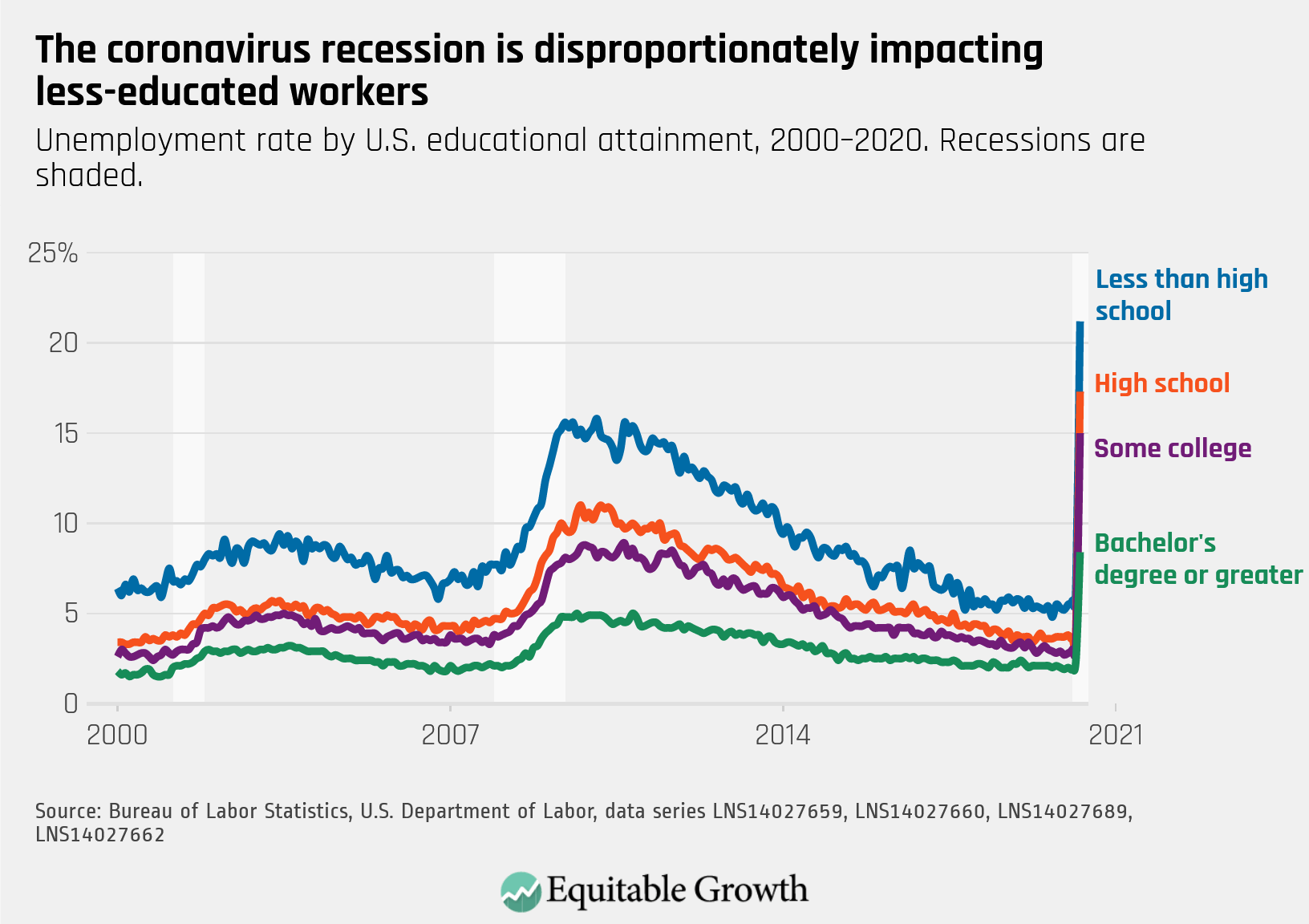

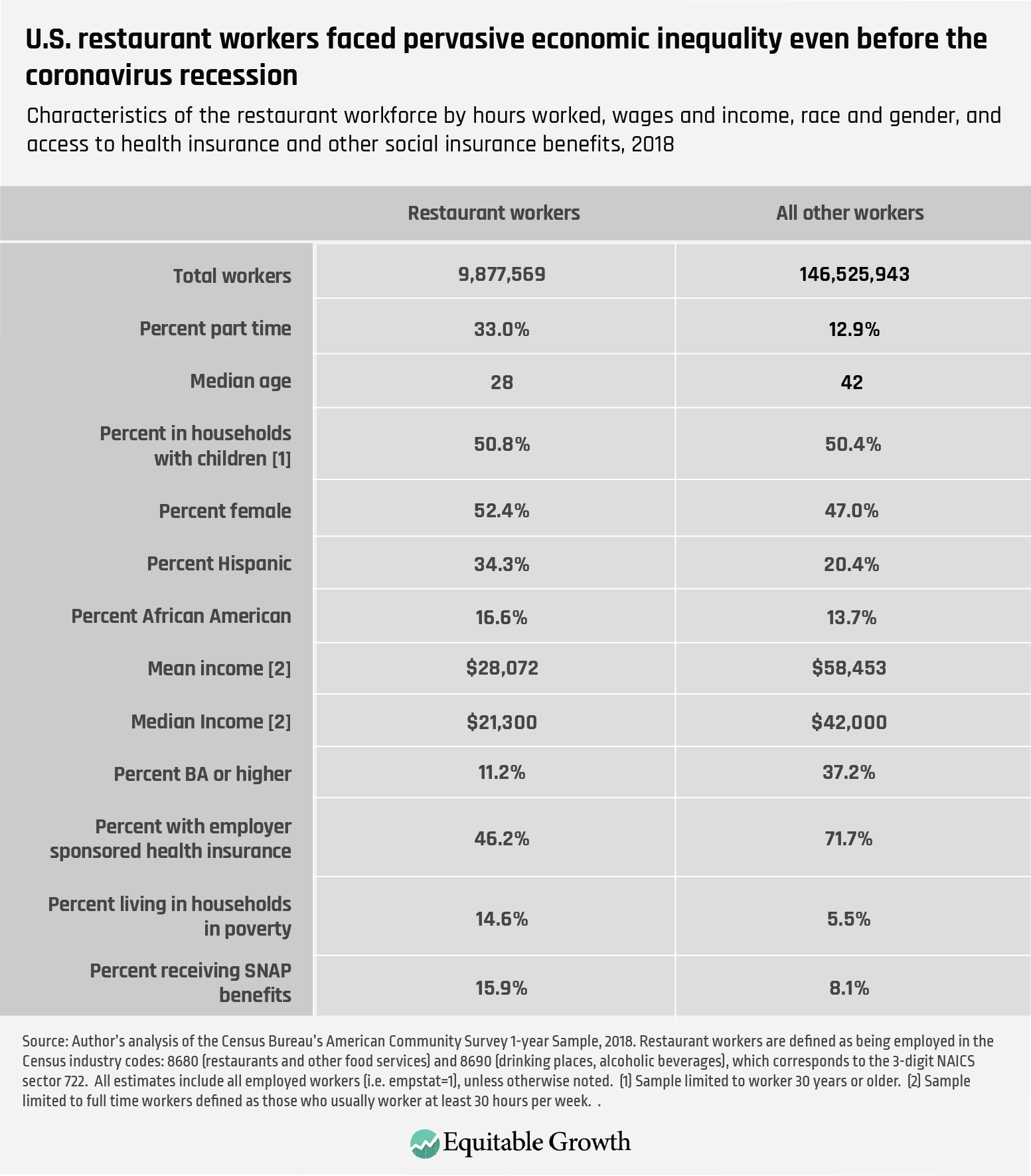

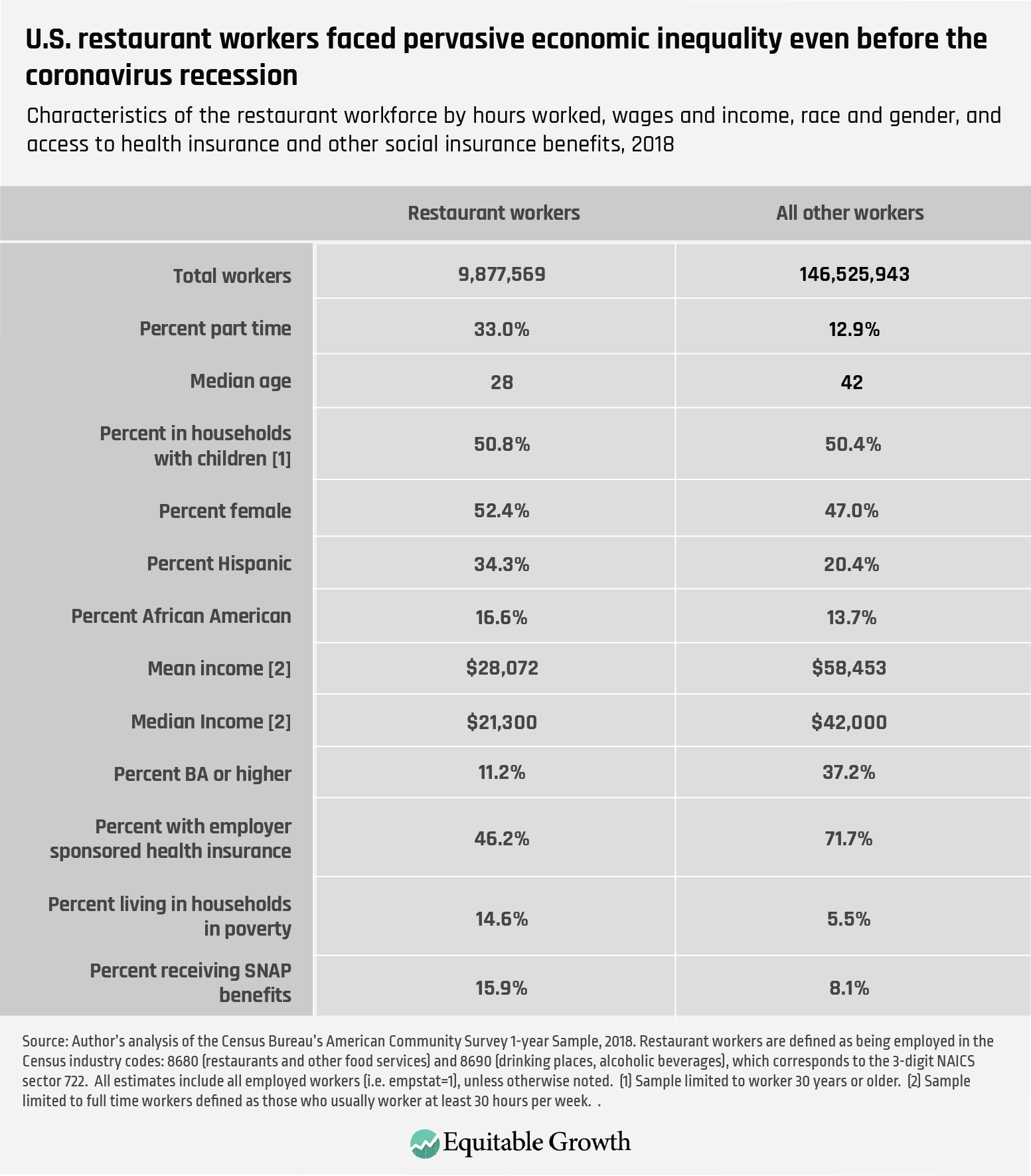

To understand the impact that the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession will have on restaurant workers, it is first critical to understand more about who makes up the restaurant workforce in the United States. Even in the absence of a public health crisis, the restaurant industry employs a relatively low-wage and economically vulnerable workforce, with high job turnover and seasonal or shift work that does not always add up to a full-time livelihood. The age of the restaurant workforce skews younger than the national average, but significant proportions of these workers are over 30 years old (45 percent). Of these older workers, half (50.8 percent) have children in their homes. The industry also disproportionately employs women and people of color. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

The median annual income of full-time workers in the restaurant industry is half of that of workers in other sectors. Because average wages in the sector are significantly lower than the rest of the economy, restaurant workers have difficulty putting savings aside for emergency situations. As a result, restaurant workers are more than 2.5 times as likely to live in households with incomes below the poverty line and are more likely to receive government food assistance.

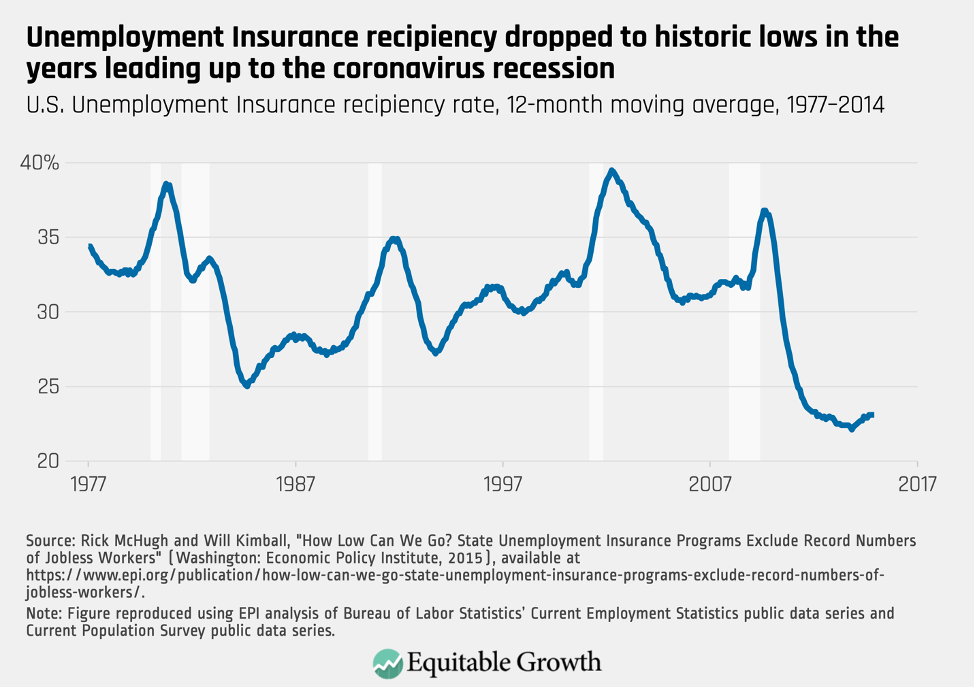

One aspect of the restaurant workforce that is more difficult to quantify with government statistics is the degree to which workers in the restaurant industry are undocumented immigrants. While the number varies from city to city, it is widely acknowledged that undocumented immigrants are an essential component of the workforce, especially in the lower-paid, back-of-house occupations, including cooks and dishwashers. One study estimated that undocumented workers make up between 8 percent and 10 percent of the entire restaurant workforce, which would be more than 1 million workers. These workers are especially vulnerable because they are not eligible for Unemployment Insurance.

Additionally, restaurant workers are less likely to receive benefits such as employer sponsored health insurance (46.1 percent versus 71.6 percent for the entire U.S. workforce). Overall, the restaurant workforce is clearly more vulnerable than the overall labor force.

The structure of the restaurant industry across the United States

Although the U.S. restaurant industry is large overall, it is made up of hundreds of thousands of individual establishments spread throughout every community in the country. It contains a variety of restaurant types, ranging from single-establishment hot dog stands to Michelin-starred palaces of gastronomy, and from national fast-food chains owned by publicly traded Fortune 500 companies to regional fast-casual, full-service chains often owned by the same big firms.

All restaurants have been hurt by the public health crisis sparked by the new coronavirus, but some have been hit harder than others. Therefore, it is important to understand the details of the structure of the restaurant industry. The overall restaurant sector—NAICS 722-food service and drinking places, in U.S. Census Bureau data parlance—includes more than 657,000 establishments across three different industries: special food services, which includes caterers and food trucks, with 44,000 employees in 2018, the most recent year for which complete data are available; drinking places, with 40,000 employees; and restaurants, with 572,000 employees. The restaurant sector is evenly split between fast-food (251,000) and full-service establishments (250,000).

The stay-at-home orders and public health emergency laws enacted by 42 states and the District of Columbia mandate that all in-person dining be shut down. These measures disproportionately hurt full-service restaurants and bars, which have either shut their doors entirely or are scrambling to convert their operations to take-out or delivery only. Fast-food establishments are still allowed to operate drive-through service and take-out functions, but with so many office workers working at home and people encouraged to leave the house as little as possible, these establishments have also struggled.

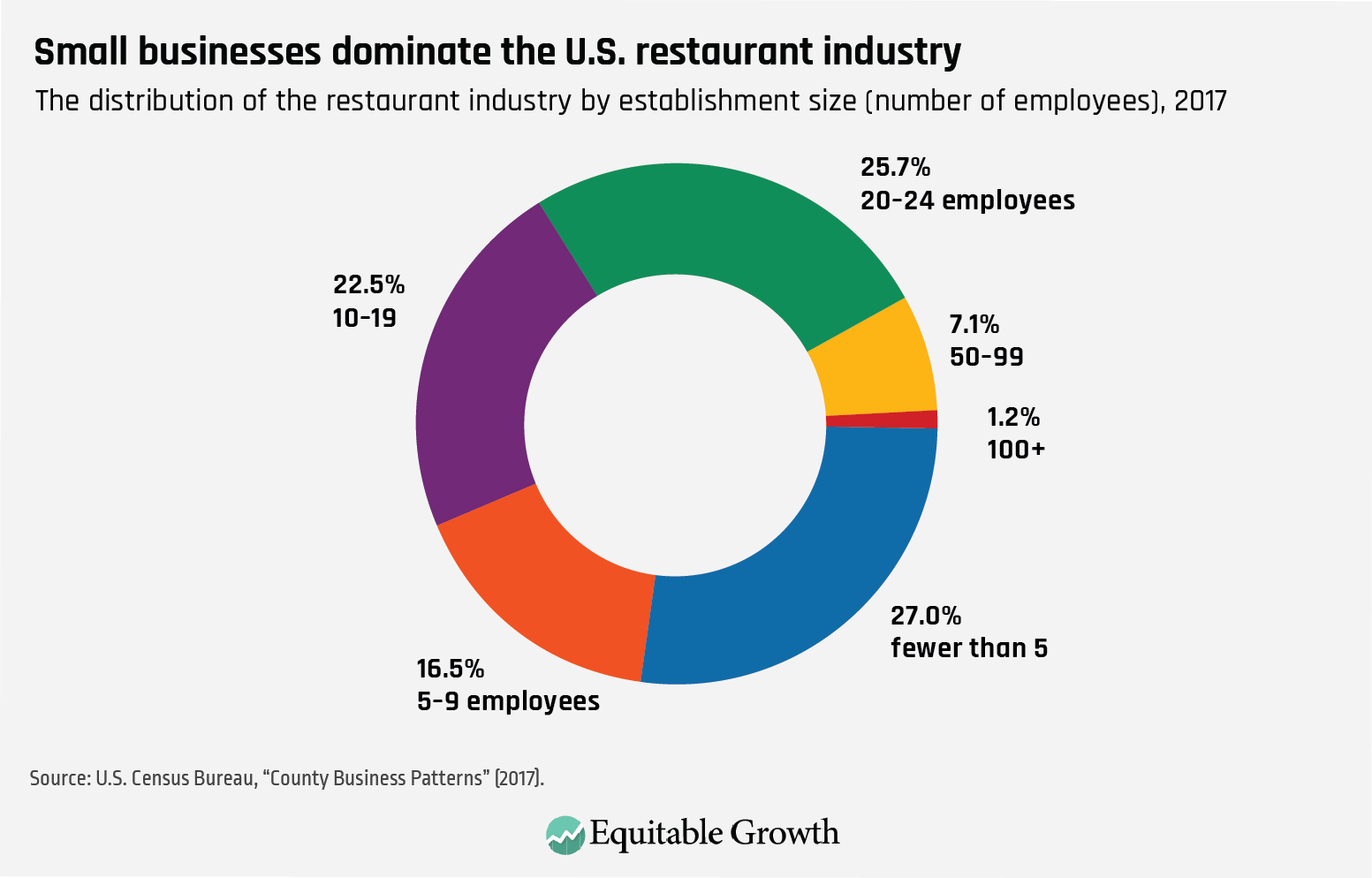

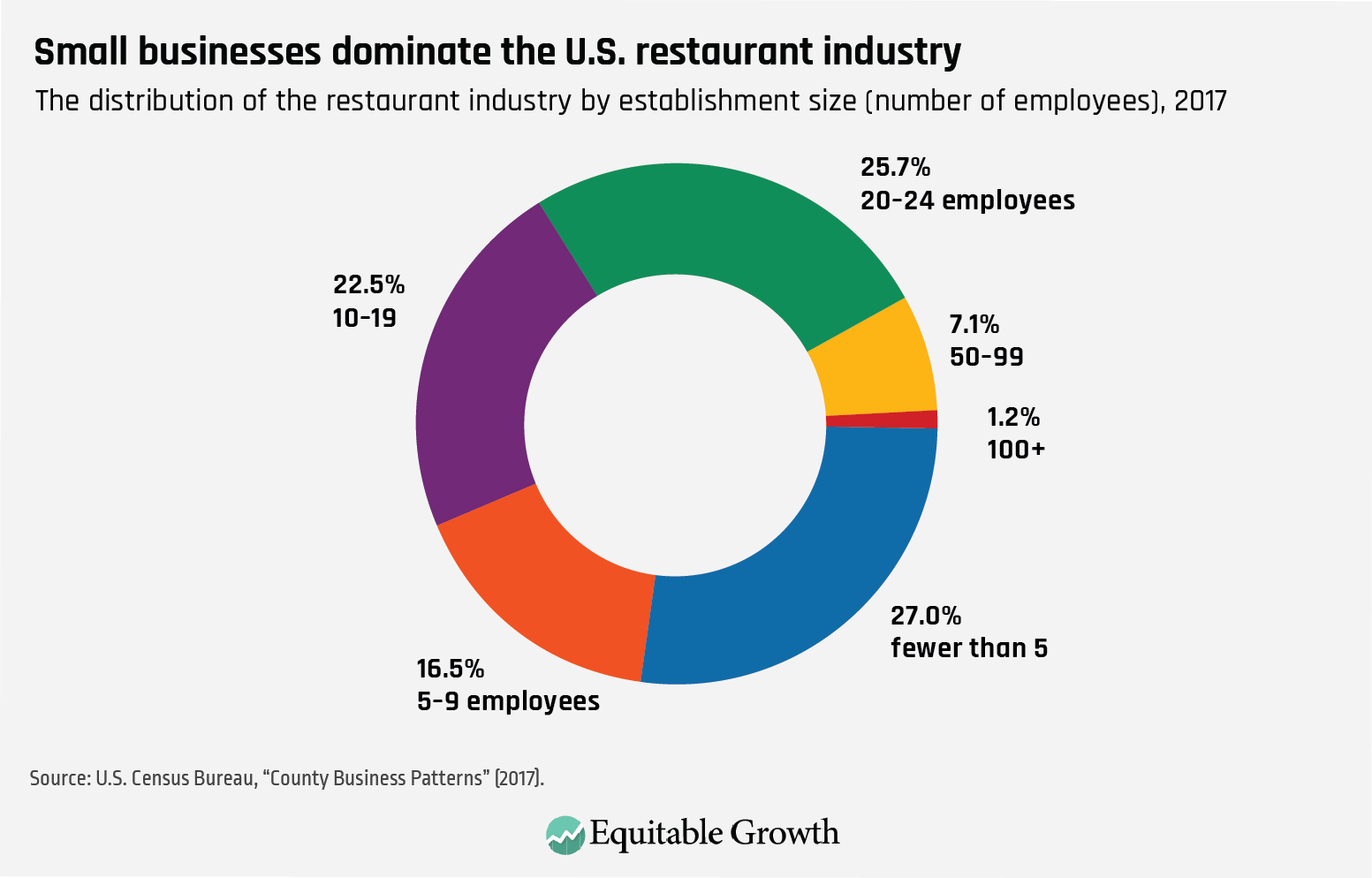

Although no statistics are available yet to understand exactly how much revenue has been lost in these sectors, a recent study shows a drop in hours worked as much as 70 percent. This is probably because small businesses make up the heart of the restaurant sector. Small business owners lack the capital reserves to carry the bulk of their workers amid such a sharp shock to their revenues. This means the vast majority of restaurants with fewer than 50 employees, alongside even smaller establishments with fewer than five, 10, 20, or 25 employees, comprise more than two-thirds of all restaurants. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

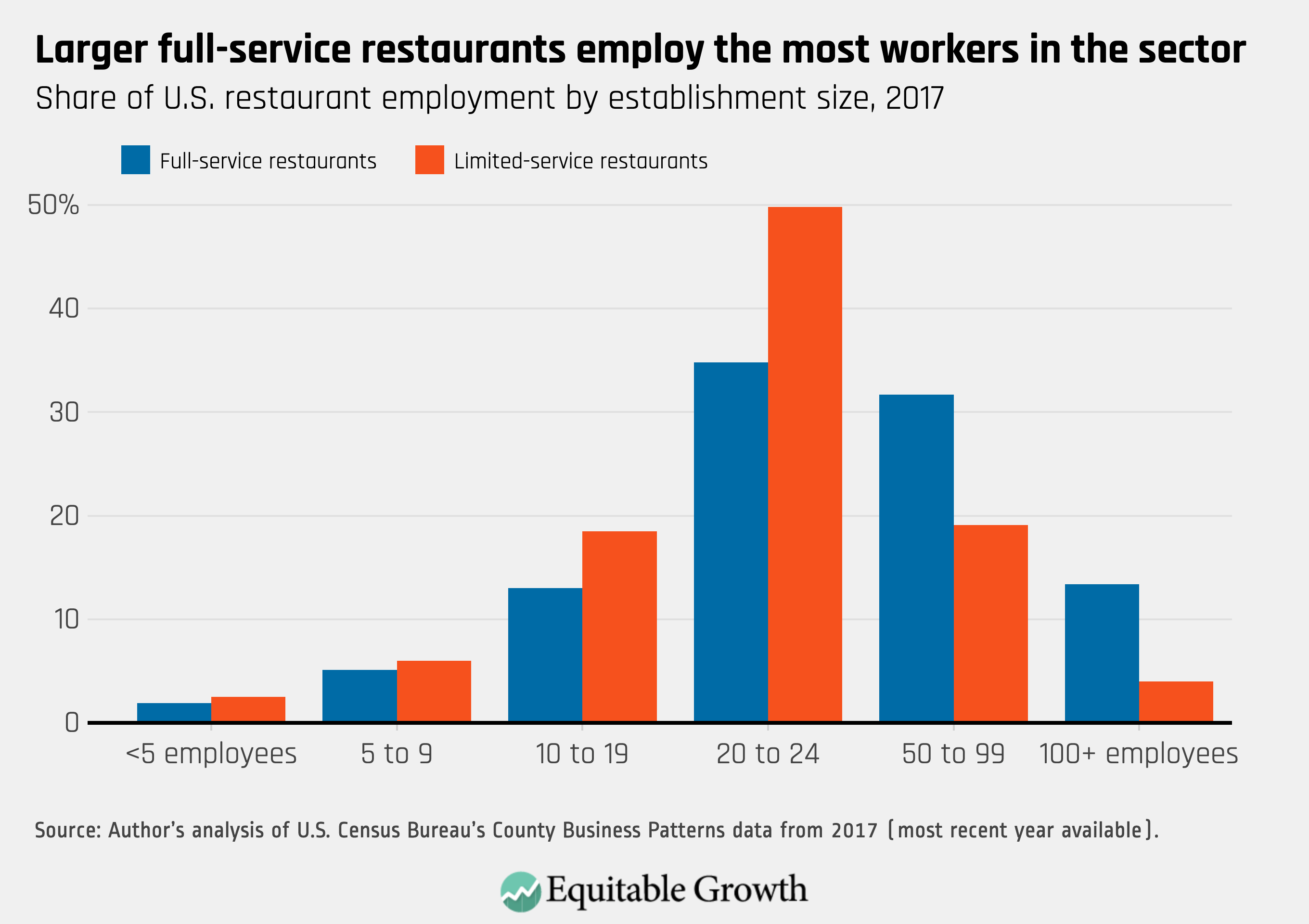

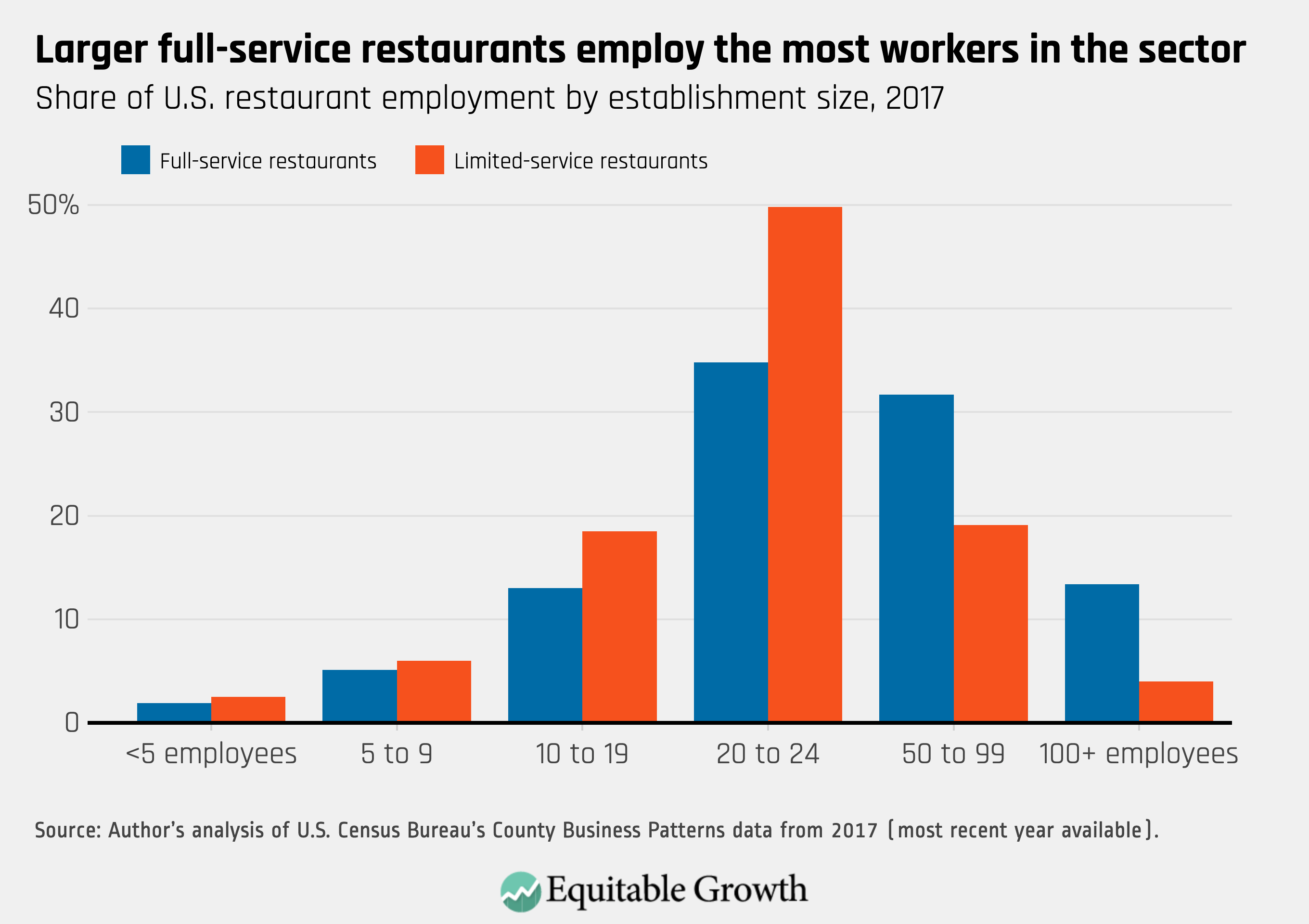

The bulk of the workforce in the restaurant industry, however, is employed in restaurants that have between 20 and 100 employees. Employment within the full-service industry skews toward slightly larger establishments. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

While government data sources yield a detailed picture of establishment sizes and employment, they cannot tell how many establishments are part of larger firms that may own or operate a chain of restaurants. Chains can either be national or operate in a single metropolitan area, but they are more likely to have the financial strength to recover from the crisis faster. According to data from the business listing database Reference USA, chain restaurants make up approximately 35 percent of all establishments while 65 percent are independently owned, standalone operations.

Yet just two large, publicly traded national chains—Shake Shack Inc. and Ruth’s Hospitality Group, Inc, the owner of the Ruth’s Chris steakhouse chain—together received nearly $100 million in SBA loans from the Paycheck Protection Program. This is indicative of how the ownership structure of restaurants is critical for inequality. Although these two companies quickly returned the funds, the public outcry underscores how small, independently owned restaurants are both more vulnerable in the crisis, and also more important for the economic recovery.

First, given that independent owners make up 65 percent of all establishments, they clearly employ the plurality of restaurant workers. Second, independent restaurants are most likely owned by local entrepreneurs. This means that their profits are re-spent in their local economies, rather than being siphoned off to distant shareholders. Lastly, research has shown that labor standards are higher in cities that are dominated by small, independent restaurants rather than large chains. Anecdotally, restaurants that have been recognized as leaders in promoting high-road business practices tend to be small locally-owned establishments that are deeply embedded in their communities.

These breakdowns are critical for federal and state and local policymakers to understand, not just to deploy coronavirus recession economic relief most effectively but also to ensure the restaurant industry emerges on the other side of the recession with a stronger and more equitable workforce and still robust small-business-owned establishments.

How the federal government assistance can help small businesses and their workers

Given the mandatory closure or partial shutdowns of restaurants across the country, there is a serious possibility that millions of workers will lose their livelihoods and hundreds of thousands of small businesses will close. The restaurant industry, like other high-touch, face-to-face service industries, is important because of its sheer size and its outsized importance in powering a swift economic recovery. The federal government, through the CARES Act, is spending the bulk of the stimulus funds to create a multiplier effect throughout the economy, putting money into the hands of workers, families, and businesses to boost overall economic activity amid the sharp downturn. Shuttered and severely limited restaurant service across the country, however, curtails the potential multiplier effects for local economies.

Gauging how the CARES Act stimulus money flows into the different parts of the restaurant sector nationwide over the course of April and in the following months will be key to grasping how much additional stimulus funding will be needed from the federal government in the legislative package expected to pass Congress. And getting a handle on how many establishments survive and how many workers the remainder of the establishments manage to re-employ will go a long way toward knowing how steep the economy’s decline, and how swift its recovery, will be.

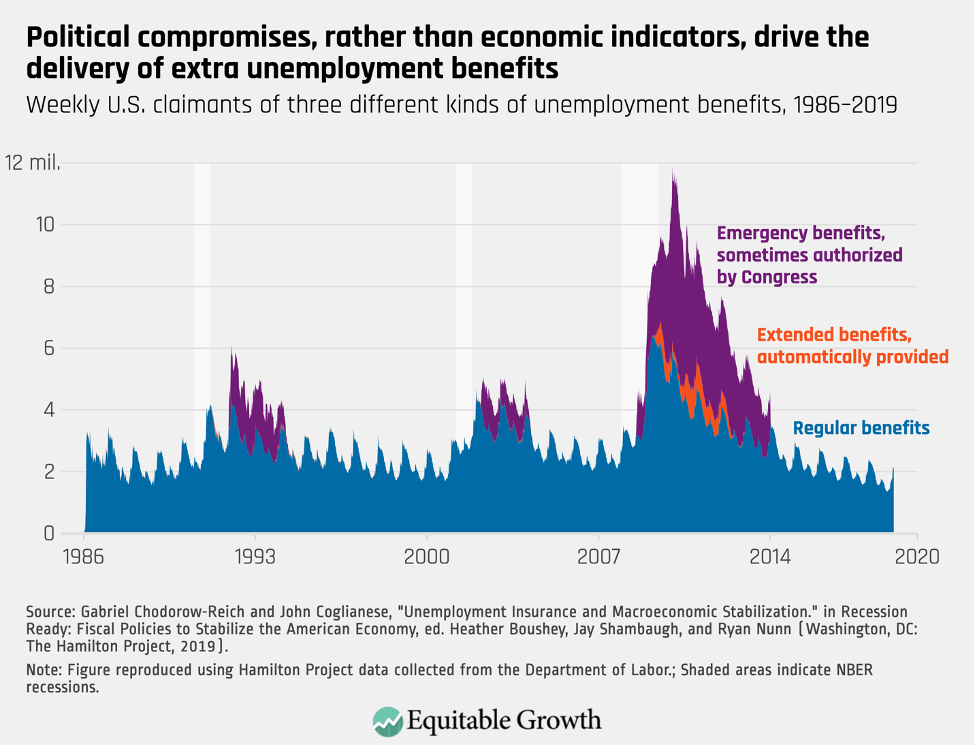

The $2.2 trillion CARES Act spending package has several provisions that have the potential to help the restaurant industry. First, nearly all workers and their families will be eligible for the one-time $1,200 stimulus checks (given their low incomes), which will help in the short run with basic expenses such as rent and food—though that funding is estimated to only cover about two weeks’ worth of expenses for the average household. Workers who were laid off will also benefit from the expanded Unemployment Insurance payments and the relaxation of job-searching requirements to access the UI funds. Restaurant workers accounted for close to 60 percent of all workers who lost their jobs in March, nearly 420,000, according to the U.S Bureau of Labor statistics, and account for the bulk of the 459,000 jobs lost in the broader leisure and hospitality category of jobs. When the data for April are released this week, the number of jobs lost will be especially grim.

Then, there’s the stimulus money that is supposed to help these workers’ employers rehire them in the coming months. The CARES Act funded $349 billion in forgivable loans for small businesses as part of the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program. (There also is a smaller pool of funds from the SBA in the form of Economic Injury Disaster Loans—which provide loans up to $10,000 with less paperwork.) Congress then added another $380 billion in funding to the PPP two weeks ago.

The Paycheck Protection Program is the main mechanism for supporting small businesses, including restaurants. Here are the program eligibility requirements for small businesses:

- They must have fewer than 500 employees.

- They must have been open and in business on February 15, 2020.

- They must make a “good faith” assertion that they were affected by the coronavirus pandemic, which will be straightforward for most restaurants as they were ordered to close their dining rooms by state or local emergency orders.

- They need to apply for a loan through a local financial institution by June 1, 2020.

All of this additional funding is either disbursed or expected to be disbursed quickly, yet understanding the parameters of the program remains important. Restaurants that meet these criteria are eligible to take out a loan for an amount determined by their prior year’s payroll expenses during the “baseline” period of February to June 2019. If a business’s total payroll for this period was $200,000, for example, then that is the maximum amount of the loan. Businesses can use the money to hire back workers, pay rent, or pay utilities for an 8-week period after the loan is taken out. These amounts would be forgiven from the principle.

The goal of the Paycheck Protection Program is to keep people on the payroll. Yet the number of people who will be considered “on the payroll” will be counted at the start of the loan, and the business is not penalized if it has already laid off workers prior to applying for the loan. Any amount that is not used for qualified forgivable expenses—payroll, which must account for 75 percent of expenses, alongside rent and utilities—would then be treated as a loan with interest rates not to exceed 1 percent.

This policy is meant to be a lifeline for businesses that were forced to close and incentivizes businesses to maintain an attachment to their workforces so that after stay-at-home orders are lifted, companies can recover more quickly. But, as is quickly becoming clear, these terms for the SBA loans are unrealistic for the vast majority of small business-owned restaurants.

Issues with the Paycheck Protection Program for restaurants

Because the restaurant industry is not monolithic, the loans from the Small Business Administration provided under the CARES Act may not be able to help prevent total catastrophe for individual restaurant owners or companies. While the agency’s Paycheck Protection Program can, in principle, be a useful tool for restaurants, anecdotal evidence on the early rollout of the program highlights several potential pitfalls for small, independently operated restaurants. (Actual data on the plight of restaurants since the swift beginning of the coronavirus recession last month may not be available and reliable for many months to come, given the chaos the restaurant sector is experiencing and the still unknowable number of restaurants that will fail.)

Still, broad trends are evident. First, the rolling appropriations by Congress for the Economic Injury Disaster Loans and Paycheck Protection Program loan programs are either already exhausted or will be shortly, and yet so many restaurants that are independently owned and very small establishments benefited far less relative to size of their economic burdens.

Second, the larger businesses and the franchises of large corporations have an advantage in applying for these loans because they have more well-established relationships with big banks. The program, in its initial phase, operated on a “first come, first served” basis, which means the majority of the funding was likely gone before the smaller restaurants ever succeed at getting the attention of a bank and applying successfully. The second phase sets aside $30 billion for smaller lending institutions so that more of the Paycheck Protection Program funds get to smaller and more ethnically diverse firms. It’s unclear at present how well that targeted lending will flow toward small restaurant establishments.

Third, there is a concern that because restaurants have been forced to close their dining rooms, they will be unable to apply these funds to forgivable payroll expenses. The reason: There is little work to be done presently and perhaps not until well into the summer or even longer, depending on how the spread of the coronavirus plays out across cities and regions of the nation and how individual state and municipal governments decide when to allow restaurants to fully reopen. Because the terms of the loans require that 75 percent of the forgivable expenses be paid to workers, there is little money available for other expenses.

There is no reason to have, say, five waiters, several bartenders, and a full kitchen staff on the payroll if the only business that can be done is limited take-out ordering. The 75 percent rule for employees means restaurant businesses basically become “pass through” entities for their employees to receive salaries provided by the federal government, which was clearly the intent of the law but which leaves restaurants—particularly smaller restaurants—unable to pay the other expenses they need to pay to stay in business.

To be sure, the Paycheck Protection Program could at least give restaurant owners the ability to retain or rehire some of their workers and then find other work for their staff on a temporary basis, such as deep cleaning or minor remodeling. But the designated lending still leaves the owners largely unable put the funds to use to not just stay in business but to also prepare their establishments for probably a very different world for them and their employees when stay-at-home orders are gradually lifted around the country.

Helping restaurants reverse the coronavirus recession and drive an economic recovery

Over the next several months, and probably over the next 12 months to 18 months, the restaurant industry is going to come haltingly back to life around the country. Depending on the course of the coronavirus pandemic this spring and summer, public health decisions will determine when restaurants are allowed to reopen. And even then, a wary public may not return in force to restaurants until a vaccine is available and widely administered.

What’s more, after restaurants are allowed to reopen, how they are allowed to do so will be key, too. Will “safe distancing” limit the number of patrons? Will carry-out and delivery services become more mainstay businesses? Will food preparation lines, as well as front-of-house bar and restaurant seating, have to change for public health reasons? Finally, will restaurants be expected to test and trace their workers and their customers for signs of infection?

At this point of the coronavirus pandemic, restaurateurs are only now beginning to think about how to answer these questions. Policymakers should not be just thinking about them but also considering how the ingrained economic inequality across the restaurant industry can be ameliorated now, so that this key sector can help power an economic recovery that is more equitable and thus more sustainable.

First, Congress needs to provide additional support to small businesses through an expansion of the Paycheck Protection Program. Given that the current allocations for this program and the Economic Injury Disaster Loan program are all but tapped out, it is essential to provide additional funding. But policymakers should consider adjustments to the program to make sure the aid is better targeted to businesses most in need, especially restaurants.

For restaurants, these reforms might include a prioritization of funding for smaller businesses. This would entail either lowering the employment size cut-off from 500 to 100 employees—more than 90 percent of restaurants have fewer than 100 employees—or setting aside separate funding pools for different business sizes or industry sectors. Congress also could consider loosening or eliminating the 75 percent threshold for payroll expenses for these small restaurants to allow more of them that don’t have the ability to add back their front-of-house staff during the stay-at-home orders to stay afloat.

Second, policymakers should continue to support policies that require businesses to expand high-road employment practices. The current crisis in the restaurant industry and the probable restructuring that will need to take place during the recovery is a time to think about what steps can be taken to ensure the restaurant industry not only comes back but also comes back in a way that is more equitable and sustainable.

Before the coronavirus recession hit, there were steps being taken by local governments, labor organizing groups and even restaurant owners to improve wages, benefits, and working conditions in the restaurant sector. Hundreds of cities have raised their minimum wages and a few, such as San Francisco, now require businesses to provide paid leave and pay into healthcare plans. Research shows that raising labor standards has improved outcomes for workers in the restaurant sector and also reduced turnover and helped to promote norms of professionalism. Studies also show that raising labor standards does not have large impacts on employment or the number of establishments.

These efforts are helping to demarcate a clear line between low-road and high-road business practices in the restaurant industry. Policymakers should keep this in mind when they will hear calls from some employers to reduce minimum wage requirements in the face of the current crisis. Instead, policymakers should consider how to help restaurant owners and their workers alike prepare for the recovery in ways that improve their resiliency and create more equitable and sustainable business practices.

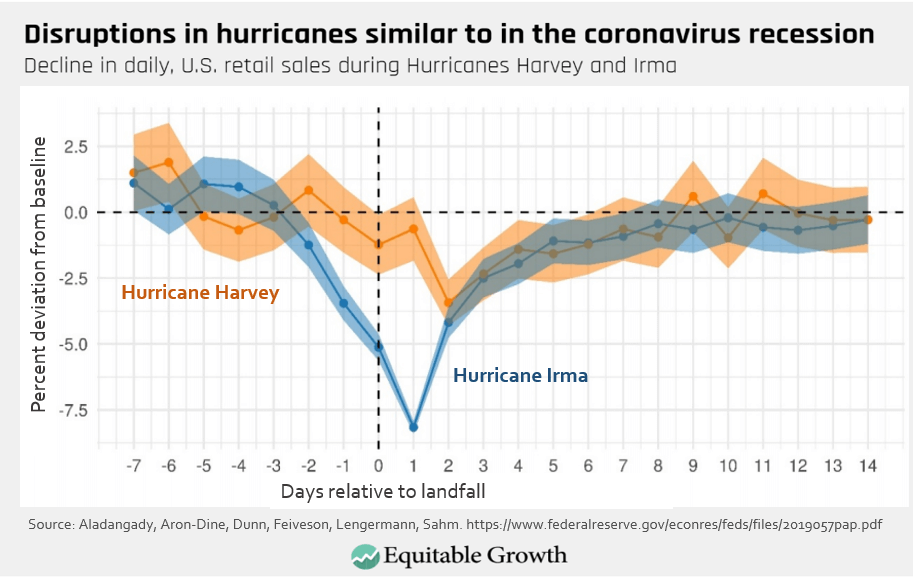

Making the restaurant industry strong and resilient before the next pandemic sweeps the nation

Policymakers need to begin considering how to develop a resiliency plan to ensure that restaurants and small businesses in general can bounce back after future pandemics or epidemics in this most high touch of high-touch services sectors. One thing these twin public health and economic crises reveal is that the United States has no real national strategy or local plans in place for resiliency in the face of pandemics. Communities in hurricane-prone areas have disaster plans on the books. The federal government has encouraged and funded “resiliency” planning in the wake of major hurricanes. And cities such as San Francisco have emergency plans in place in the event of a major earthquake.

This kind of preparation for natural disasters is now a major subfield of research in urban planning. While the new coronavirus is not purely a natural disaster, there are no existing insurance programs to help businesses or workers in the high-touch service economy during this type of crisis. Given what we are all witnessing right now, what lessons can we learn that might help avoid some of the painful economic outcomes in future pandemics?

First, Congress may have to deal with the controversy over insurance companies not covering the pandemic as a legitimate business interruption claim. The federal government can act in two different ways to make sure that effective business interruption insurance coverage is in place for the next public health emergency. The government can use its regulatory powers to ensure that pandemics are covered under existing business interruption insurance policies. But if the losses claimed under this program would bankrupt insurance companies, then the federal government could set up and support financially a more robust business interruption insurance program specifically for public health disasters. Under such a program, businesses would pay some amount each year that goes into a pool for a time when a public health emergency forces them to close. Insurance carriers would be backed by the federal government, which already backs the national flood insurance program.

Second, policymakers need clearly defined and communicated government plans at the state and local levels in place for the next pandemic. Public health policymakers need to develop guidelines for when businesses in the services sector are expected to shutter their doors should they find themselves trying to get ahead of the curve of a future nascent pandemic, which, of course, did not happen in 2020 with the new coronavirus pandemic. And they need to plan for how and when service-sector businesses can reopen should a future pandemic get ahead of public health officials.

Right now, different states and cities and even regions are trying to game this problem out. If there had been had a plan in place, then there would be less uncertainty among businesses that are wondering now if they should plan for 2 weeks of closure or a year. Clearly, the nature of the public health crisis will dictate the specifics of reopening, but the coronavirus experience will likely lead to lessons of what works and what does not.

Conclusion

The need to further assist the restaurant industry is clear. With 11.8 million workers employed in bars and restaurants across the country, the restaurant sector represents a large and important portion of the U.S. service-based economy. The eventual economic recovery after this public health and economic disaster will depend on the ability of consumers to spend money in their local economies, and a vibrant restaurant sector is a critical part of this process.

Restaurant workers themselves are especially vulnerable. Before the shutdown, restaurant workers were paid low wages, lacked employer-sponsored benefits such as healthcare and paid sick leave, and were more likely to be living in poverty. Finding ways for this workforce to remain afloat and attached to its jobs is essential, as is continuing efforts to improve job quality during the recovery.

This issue brief also shows that the restaurant sector is dominated by small businesses, the vast majority of which are much smaller than the 500-employee cut-off for the Paycheck Protection Program. The majority of these small businesses are single establishments that are independently owned by local entrepreneurs who live and spend money in the communities in which they operate. While the restaurant sector has endured the majority of the job losses due to the pandemic, it was less likely to benefit from the support in the CARES Act. In considering additional legislation to help the U.S. economy, Congress should think about ways to better target aid to struggling restaurants.

The U.S. restaurant industry, of course, is more than just a set of numbers. There is a priceless cultural value to these establishments that goes beyond just the size of its workforce or the scope of its economic impact. The industry is a part of the fabric of everyday life in communities across the country, from the small-town diner in rural Idaho to the trendy fusion taco truck in downtown Los Angeles to the family-run Italian restaurant in nearly any city in the United States. Restaurants are complex. There are essential human connections that happen at restaurants between workers, employers, and customers that are simply missing now. Restaurant owners, worker advocates, and nonprofit groups are all working tirelessly to find a way to stay afloat and maintain the prospect of reopening. Congress should do more to extend support to this vital piece of the American economy and culture.

—T. William Lester is an associate professor at the Department of City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, specializing in economic development.