First Jobs Day report since the onset of the coronavirus recession exposes a U.S. labor market in crisis

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics this morning released its monthly Employment Situation Summary, the first Jobs Day report to capture just how hard the coronavirus recession is hammering the U.S. labor market. The new report, coming after yesterday’s towering 6.65 million Unemployment Insurance claims, means that after decades of rising economic inequality, the decline in the power of unions, and the erosion of the safety net, U.S. workers are going to be particularly unprepared for this sharp and sudden economic downturn.

Today’s Jobs Day report shows that after months of historically low unemployment, the unemployment rate climbed to 4.4 percent for the first time since August 2017. The share of the population that is employed dropped to 60.0 percent, a massive 1.1 percentage point decline from the previous month. The job losses were markedly worse for those with less education and unemployment increased by 1.4 percentage points for Hispanic workers, compared to the average across workers of 0.9 percentage points.

So far, service-providing industries have been the hardest hit in this recession. Today’s report contains labor market data collected during the week ending March 14, before any city or state had ordered the closure of nonessential businesses to slow the spread of the new coronavirus. Yet, by the second week of March, many restaurants, theaters, stores, and hotels had experienced a drop in demand or closed their doors voluntarily, leading to layoffs and reduced shifts for many service workers.

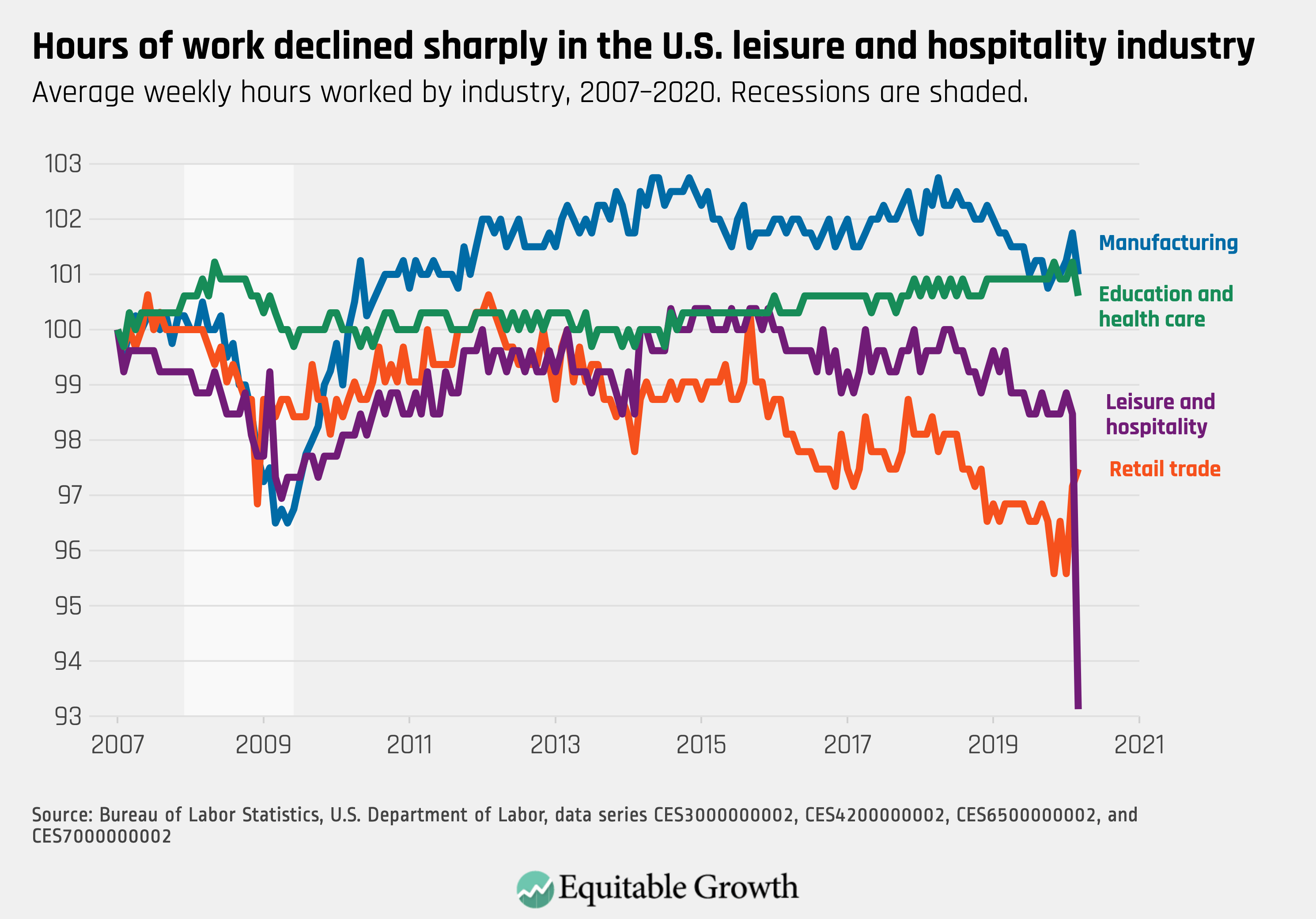

Evidence of economic downturns generally appears in hours of work data first, since employers tend to prefer cutting hours to laying off workers. Today’s Jobs Day report shows that hospitality experienced the biggest declines in hours. Average weekly hours worked by employee fell to 1.4 hours to 20.4 hours per week, compared to 25.8 hours last month. Manufacturing also saw a decline in average hours of 0.3 fewer hours per week (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These movements in average weekly hours point to how the coronavirus recession is likely to be different from the Great Recession of 2007–2009, as well as why economists expect to see the sharpest rise in unemployment of the past few decades. During the Great Recession, workers in goods-producing industries such as construction and manufacturing experienced the steepest drops in both employment and hours of work.

The current economic standstill, however, has been particularly hard on the retail and leisure and hospitality industries which, combined, employ more than 32 million workers, or more than 25 percent of the U.S. workforce. The Jobs Report released today reflects data from mid-March, when employment declines were steepest in leisure and hospitality, with a loss of 495,000 jobs, and only starting to decline in retail, with a loss of 46,000 jobs.

The service-sector jobs with the highest risk of unemployment are also some of the lowest paid and most insecure, meaning that the workers most likely to experience layoffs or cuts in hours are among the least likely to have the resources to weather a loss in income. With average hourly earnings of $16.83 and $20.26, respectively, the hospitality and retail industries are the worst paying industries in the United States. They also fall behind most sectors in terms of access to fringe benefits and earnings and hours stability.

A severe hit to service-sector jobs is therefore likely to make already-precarious jobs even more insecure. While it’s never a good time for a recession, after four decades of rising economic inequality, this recession could be particularly hard for low-wage workers, especially workers of color.

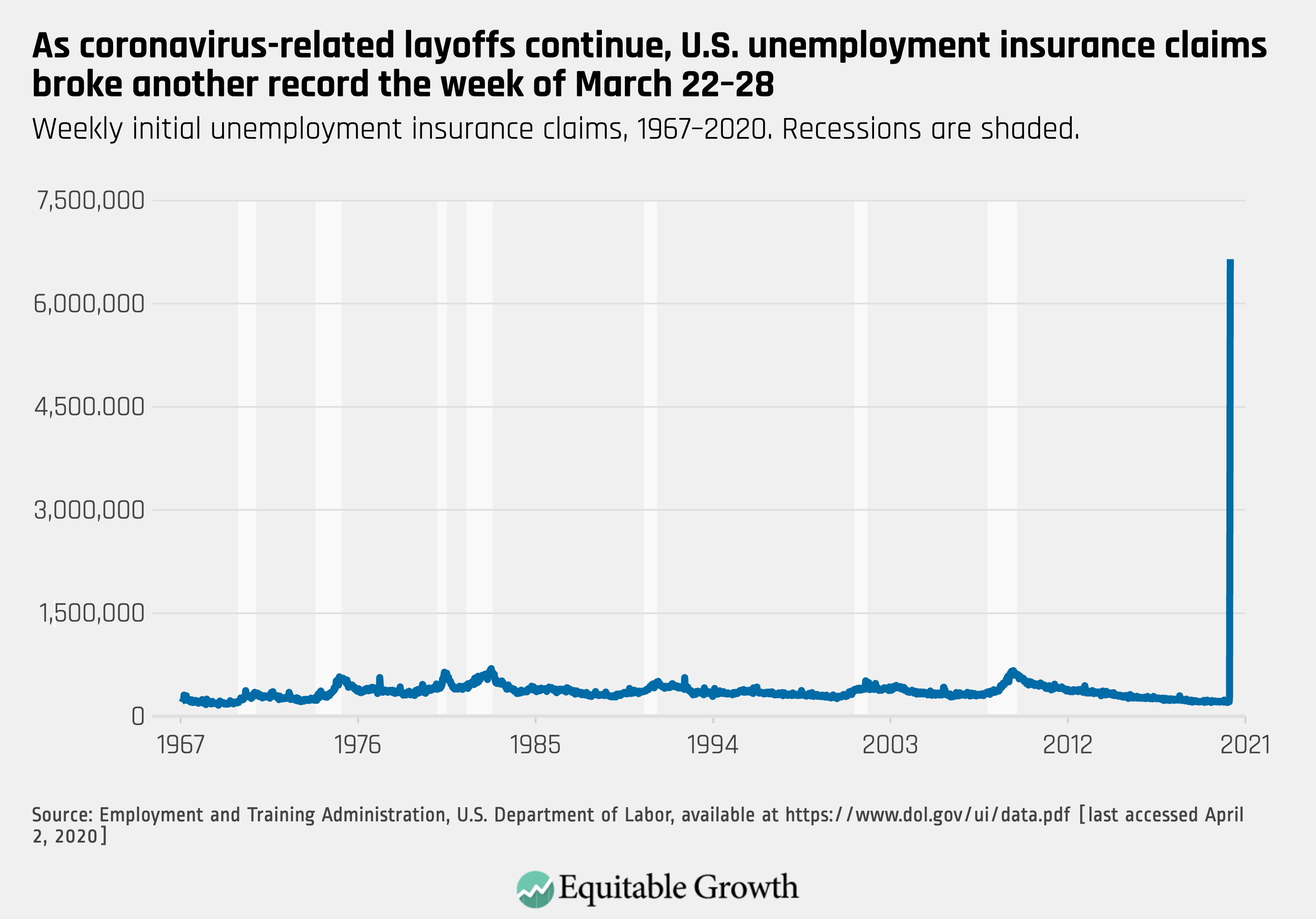

The Department of Labor’s Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Report provides more timely data on how quickly joblessness is rising. Released yesterday, the latest report shows that during the week ending March 28, there was another record-shattering number of initial Unemployment Insurance benefits claims. That week, 6.65 million workers filed for unemployment benefits—3.34 million more than the week before and 5.95 million more than the pre-pandemic historical high of 695,000. All in all, more than 10 million workers filed for unemployment benefits in March, which is likely going to be worse than the starkest months of the Great Recession. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

But even those numbers represent an underestimation of how fast unemployment is rising. Previous research shows that, mostly due to eligibility issues, only about a quarter of U.S. workers who lost their jobs applied for Unemployment Insurance. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Stimulus Act, which became law late last week, modified eligibility criteria to include independent contractors, freelancers, and those with a limited work history. This was one of other necessary measures taken to expand the scope and generosity of the Unemployment Insurance system, although further expansions will probably be needed because the downturn will likely last longer than the four-month expansion of unemployment benefits in the most recent relief package.

What’s more, after years of insufficient funding, many states’ unemployment offices are struggling to both navigate the new guidelines and process the tsunami of incoming claims, leaving them unable to record all new applications. The speed and depth of this flash recession is beyond the capacity of states to manage without federal support.

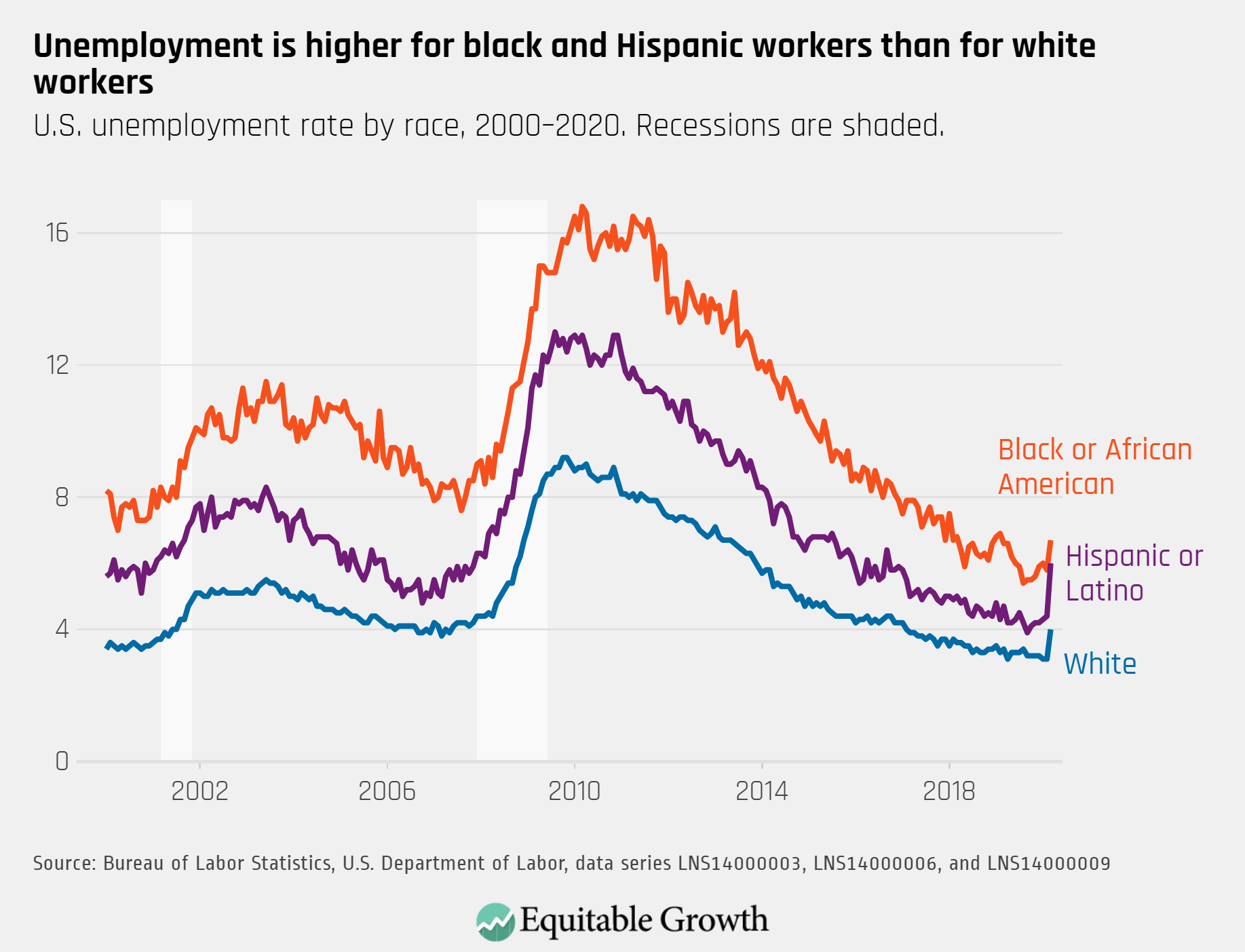

The surge in unemployment benefits claims highlights yet another challenge for already vulnerable groups in the labor market. Experience from the Great Recession shows that despite facing far greater rates of joblessness, low-wage workers and workers of color were less likely to receive Unemployment Insurance benefits. For instance, research shows that in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession, black unemployed workers were almost 10 percentage points less likely to receive unemployment benefits than their white counterparts, despite facing an unemployment rate that was twice as high. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The Unemployment Insurance and Employment Situation reports capture only a very preliminary picture of how the coronavirus recession is hitting workers. The past three weeks have upended the U.S. labor market, with some experts expecting the unemployment rate to be well above 10 percent by May 8, the release date for next month’s Jobs Day report. It will reflect the loss of millions more jobs and the sharpest rise in unemployment in living memory.

We are in a recession, a very severe recession.