This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

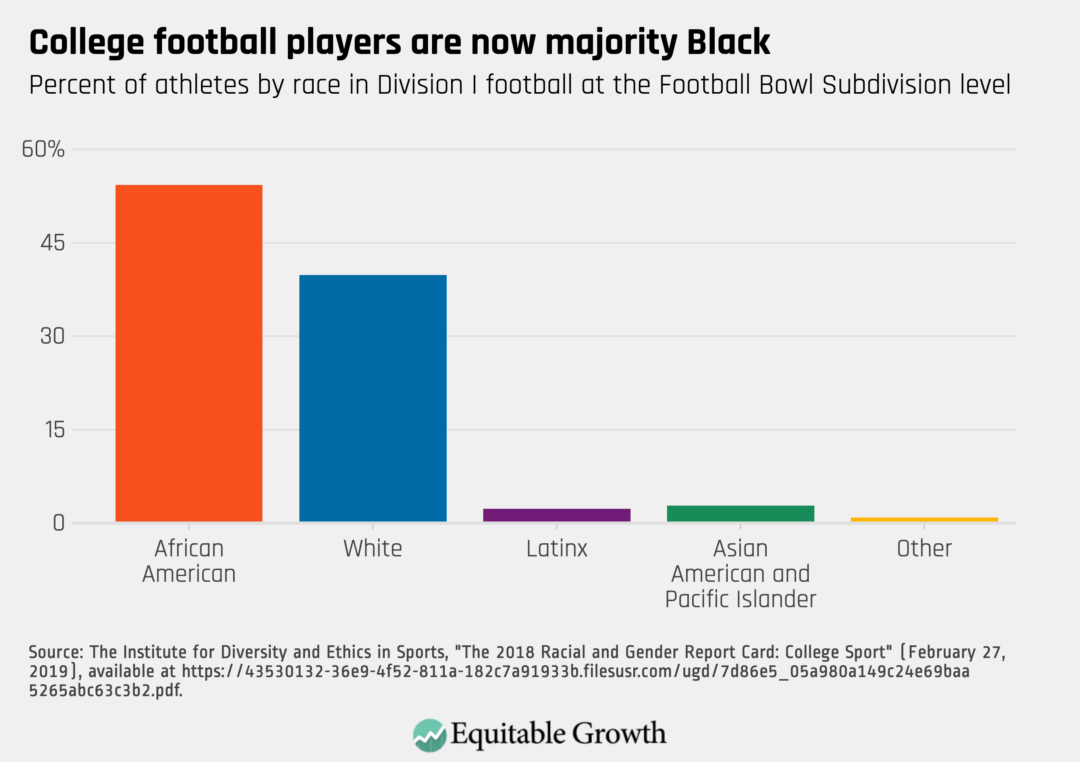

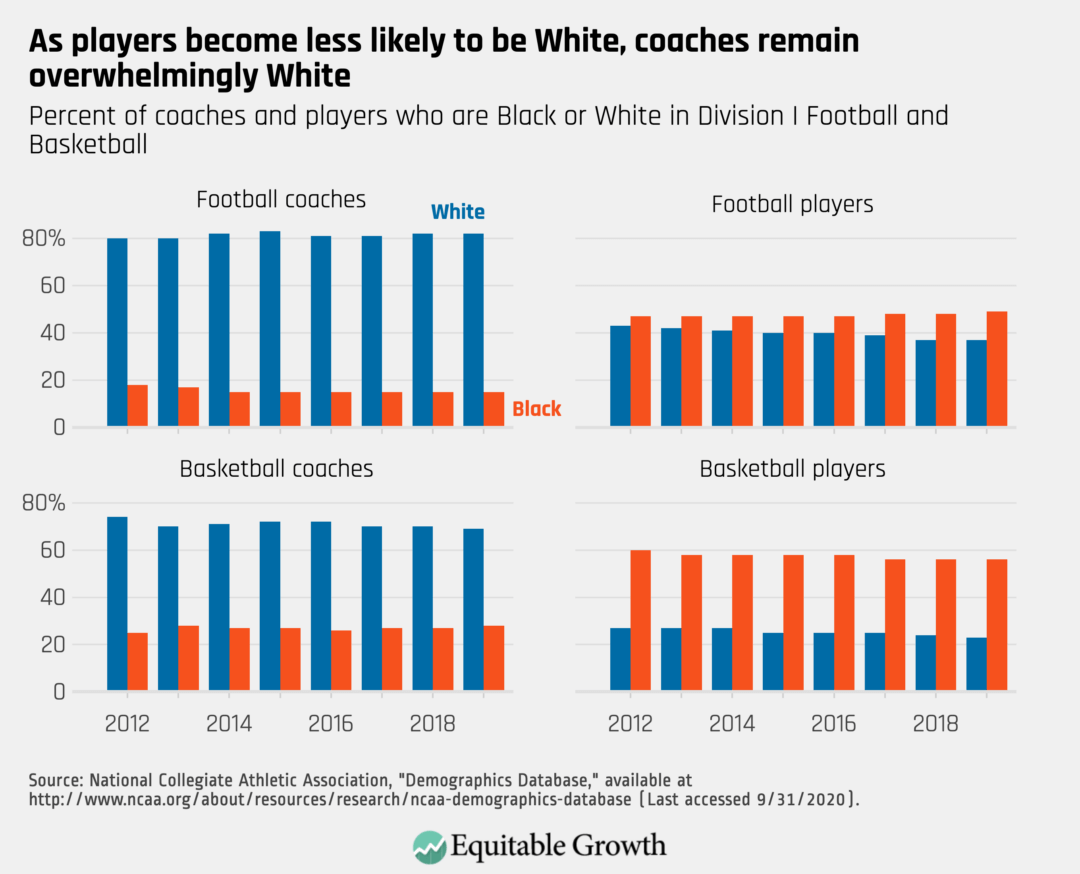

The economics and economic inequalities of college sports, and college football in particular, have long been ignored, with both the physical and economic well-being of athletes often overlooked by universities and fans alike. But the coronavirus pandemic is raising questions about what the economic effects would be of deferring college sports by a year due to the out-of-control public health crisis. Kate Bahn looks at why two top college sports conferences have decided to suspend all activities until at least January 2021, while the other three top university-level leagues are forging ahead. The lost revenue from cancelling a season or a full year of college football will have a dramatic impact on the economies of college towns and the purses of universities across the United States. But, Bahn asserts, with the coronavirus and its corresponding disease, COVID-19, predominately affecting people of color—including students of color who are now the majority of college football athletes, even as coaches remain mostly White—the existing structural and economic inequalities facing Black and Latinx students and their families are being brought to the foreground, as is the longstanding call for student athletes to be recognized as a labor force, entitled to proper pay and workplace protections.

Every month, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS. The BLS recently released the latest data for July 2020. Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn put together four graphics highlighting key data from the release, including that workers are beginning to feel more confident about the labor market (reflected in an increasing rate of those who quit their jobs) and that job openings are continuing to yield fewer hires.

Catch up on Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads, in which he provides his take on content from Equitable Growth and across the internet. This week’s articles include Equitable Growth’s August 2020 Jobs Day coverage, an in-depth look at one of our 2020 grant descriptions, and more.

Links from around the web

In August, a group of U.S. senators announced plans to introduce legislation that outlines a so-called college athletes bill of rights, which would provide NCAA players with proper pay, healthcare, lifetime educational scholarships, and additional benefits. The co-sponsors of the legislation hope this bill of rights will get rolled into existing bills making their way through both chambers of Congress on NCAA policies regarding the use of the name, image, and likeness, or NIL, of college athletes. Sports Illustrated’s Ross Dellenger dives into the proposed bill of rights, which intends to “advance justice and opportunity” for athletes, particularly with regard to monetary compensation and representation in decisions that affect them. It would also enhance transparency regarding school finances, revenues, and expenses, and importantly includes college athletic departments—which are notoriously secretive about their spending—in this requirement.

College sports is not the only industry in which those in leadership positions tend to be White. A New York Times review of the more than 900 most powerful people in the United States—from politics to entertainment to law enforcement—shows that even as the U.S. population becomes more diverse, the vast majority of those in power are White. Denise Lu, Jon Huang, Ashwin Seshagiri, Haeyoun Park, and Troy Griggs look at 922 officials and executives, and find that 20 percent identify as Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, multiracial, or otherwise a person of color, even as more than 40 percent of Americans identify with one of these groups. The co-authors then look at each specific field to show the diversity—or lack thereof—in its leadership ranks, noting that “even where there have been signs of progress, greater diversity has not always translated into more equal treatment.”

An in-depth look in The Washington Post at a dilapidated motel in Orlando, Florida, just down the road from Disney World and Universal Studios, reveals a devastating present and foreshadows a bleak future for many communities suffering similar fates. Greg Jaffe writes that the motels along this stretch of highway have long been a barometer for the economy, gathering budget-conscious tourists in good times and, during tougher times such as today, transforming into last-resort shelters for struggling workers and their families. After the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the housing collapse in 2008, the number of families staying in these increasingly decrepit motels rose, thanks to a lack of both well-paying jobs and low-income housing in the city. Now, Jaffe finds, some motel owners are abandoning their properties for the residents to maintain, often leading to power outages, pest problems, rising addiction and mental health crises, and crumbling infrastructure. A few local charities are working to help these vulnerable and hard-hit families, but more assistance is needed—and doesn’t appear to be imminent. It’s a devastating look at what could only get worse if policymakers at the local, state, and federal level continue to ignore the problems facing many low-income communities amid the continuing coronavirus recession.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “College football’s inequality dilemma amid the coronavirus recession” by Kate Bahn.