Weekend reading: Supporting and protecting workers during the coronavirus recession edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

The importance of paid family, medical, and caregiving leave for all U.S. workers throughout the coronavirus pandemic and looming recession cannot be understated. These policies are not just benefits, but also necessities—and are especially needed during this public health and economic crisis. In an issue brief covering the different types of state-level paid time away from work, Jack Smalligan, Chantel Boyens, and Alix Gould-Werth explain the differences between paid sick days, paid medical leave, and paid caregiving leave and why each is important from both an economic and health perspective at this critical moment. In conjunction with the issue brief, Equitable Growth produced factsheets covering benefits for workers and the economy of paid medical and paid caregiving leave, as well as a factsheet on the research about the policy design of these programs.

In addition to these badly needed worker-protection policies, there are many other ways policymakers can confront the coronavirus recession that is either about to hit or already hitting the U.S. economy. Heather Boushey and Somin Park outline the various ways that lawmakers can keep income flowing and pause the expenses of individuals and businesses in the United States, ensuring that once the health crisis passes, people and companies will be ready to get back to work. Boushey and Park’s proposals include providing paid leave, boosting Unemployment Insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, helping small businesses pay their bills, ensuring that corporate assistance puts workers first, distributing direct cash payments to Americans, and increasing support to states for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. These and other ideas would protect and support workers and their families in desperate need of assistance.

Another suggestion to prevent a long-term recession as a result of the coronavirus outbreak is to make the U.S. government the payor of last resort. This idea, put forward by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman during an online conference this week, would essentially have the government pay wages and essential business maintenance costs in order to prevent locked-down businesses from going bankrupt and to allow idle workers to continue to be paid instead of being laid off. The amounts given to businesses do not need to be exact and would be verified and corrected once the lockdowns have ended, allowing businesses to “hibernate without bleeding cash.” The program would also be limited in duration, likely to three months. While this would obviously not fully offset the economic costs of a coronavirus recession, it would lay the foundation for a quick rebound once the public health threat is contained.

With the likely passage this week of a $2.2 trillion stimulus package, Congress has fought back—and, thus far, fought back hard—against the immediate effects of the coronavirus health and economic crisis, writes Claudia Sahm. One of the most commonly discussed elements of the new stimulus package is the direct cash payments that will go to Americans, called recovery rebates in the legislation. These rebates will cost more than $250 billion, or 2 percent of consumer spending in 2019, and will go to 8 in 10 people in the United States. Sahm XX covers XX what, exactly, we know about the rebates, why they are a sound policy idea—and unfortunately, why they will probably not be enough to truly stave off a deep and severe recession.

The federal government’s slow response at the start of the outbreak was a costly misstep, but President Donald Trump can correct this wrong by appointing so-called COVID-19 czar, argue Susan Helper, David Clingingsmith, and Scott Shane. In light of the fast-paced nature of the coronavirus crisis and its grave threat to both the lives and livelihoods of Americans, the president must appoint a coordinator who can “use federal powers to direct the production of needed medical supplies, including personal protective equipment, ventilators, test kits, hospital beds, and negative-pressure rooms, which help prevent cross-contamination.” Doing so would allow the federal government to execute a coordinated, quick, and apolitical response, and deliver much-needed medical supplies to hospitals and care providers across the United States.

There are a variety of other ideas that can be activated to support hospitals and healthcare workers, Helper, Clingingsmith, and Shane explore in another column. These ideas include converting now-empty hotels in the cities worst hit by the outbreak into temporary hospitals with negative-pressure rooms, and retraining medical personnel from different fields to treat COVID-19 patients. But the proposals must be paired with longer-term restrictions on social activity, which inevitably will have economic ramifications—and action must be taken swiftly in order to prevent the coronavirus recession from becoming the coronavirus economic depression.

Links from around the web

The coronavirus outbreak and resulting economic downturn are making clear the holes in the social safety net for millions of workers, writes Shelly Steward for the Aspen Institute’s blog, particularly those workers with demanding and often unpredictable schedules and few job protections. While many companies have committed to expanding their paid sick leave policies due to the crisis, this is not enough. Many of these policy changes are only in place for the duration of this coronavirus outbreak, and many require an official COVID-19 diagnosis. Steward urges Congress to consider long-term and more universal solutions—and in the meantime, states and cities can act to fill the gaps.

Many gig economy workers are facing an impossible choice: risking COVID-19 or starving, report Veena Dubal and Meredith Whittaker in The Guardian. Because companies such as Uber Technologies Inc. sometimes classify their workers as independent contractors, they don’t have to provide benefits to their drivers, including access to the minimum wage or unemployment insurance. Though this is supposed to be illegal—particularly in the state of California, where a law was recently passed to prevent this misclassification of workers—it still happens, and it is particularly harmful amid the coronavirus outbreak, Dubal and Whittaker write. (As a side note, the $2.2 trillion stimulus package would provide access to Unemployment Insurance to gig economy workers, so they won’t have to keep making this choice.)

Said stimulus package is a good start, but more must be done in the coming weeks and months, argues Dylan Matthews for Vox. While the package is an extraordinary display of bipartisan compromise, and a “shockingly ambitious measure from a Republican legislature,” it is imperative that more continues to be done as the country slips into a recession in order to strengthen the measures included. Matthews looks back at the previous economic crisis—the Great Recession of 2007–2009—and the stimulus package passed by President Barack Obama, as well as the lessons it can provide for the current crisis and package, detailing what is commendable and what needs improvement in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act.

The workers most at-risk of exposure to coronavirus are also those who tend to be paid among the lowest salaries, find Beatrice Jin and Andrew McGill in Politico. In an interactive graphic, the authors show how many of the 24 million workers making less than $35,000 per year—from cashiers and bartenders to nursing assistants and paramedics—are facing the highest risk of injury during the coronavirus pandemic. The majority of this group, making up about 15 percent of the American workforce, is so at-risk because their livelihood typically depends on direct human contact and because workers in their salary tier are less likely to receive benefits such as paid sick leave that would help them weather any disruption in work. They also typically occupy jobs where remote work is not an option.

The ability to work from home also reveals a stark contrast in race and education level throughout the U.S. economy, write Christian Davenport, Aaron Gregg, and Craig Timberg for The Washington Post. A recent survey shows that people of color and the high-school (or less) educated make up the majority of those who have to continue going to their workspaces during the coronavirus outbreak—and those whose health is most at risk and whose incomes are most likely to suffer during the economic downturn. Davenport, Gregg, and Timberg show how the inequalities of the labor market are being thrust into light in new ways: Those who can work remotely won’t face the same threats to their health and livelihood as those who can’t. Poor people of color make up the majority of the latter group, while better-off white and Asian American workers fall largely in the former group.

Friday Figure

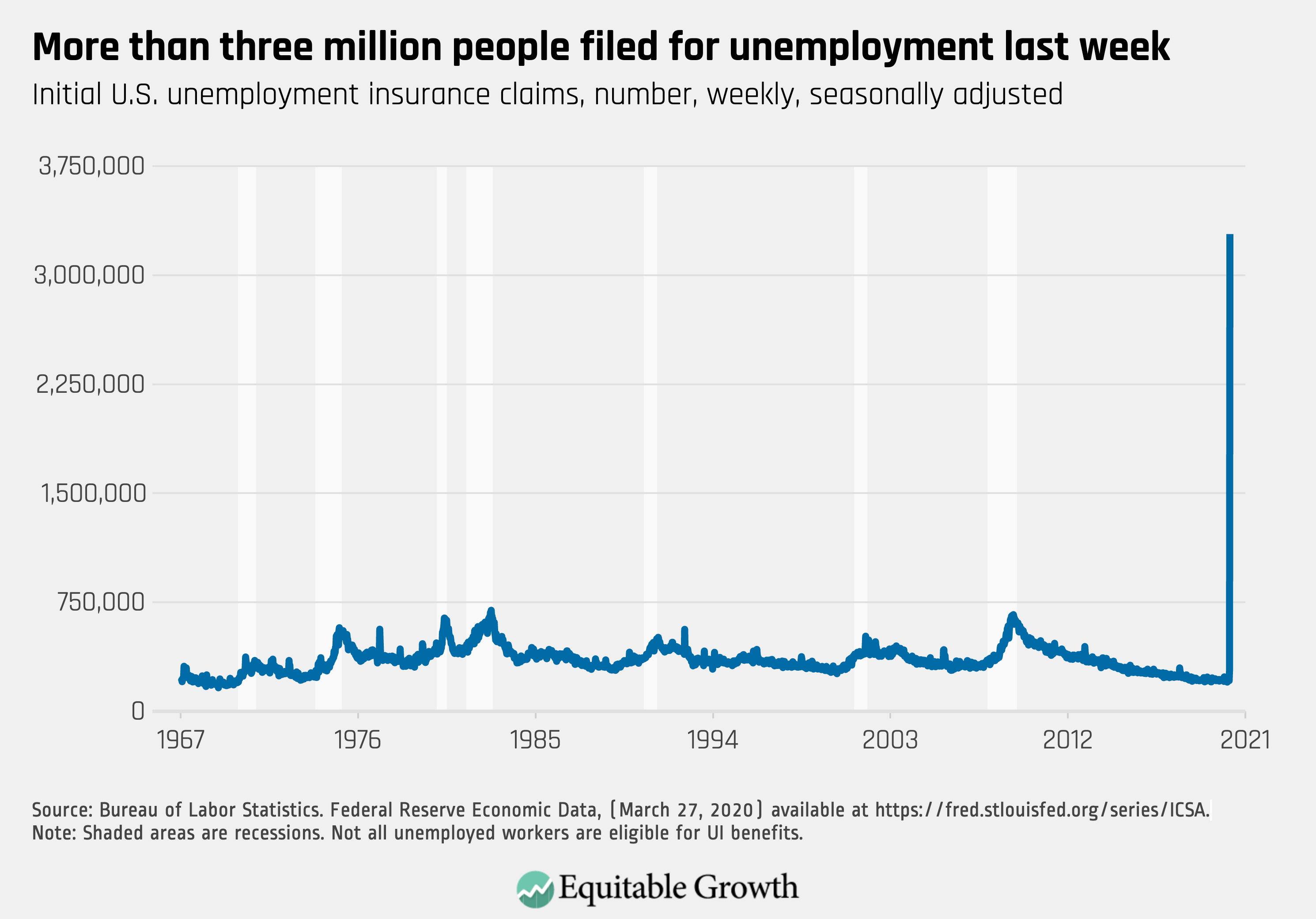

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s Twitter thread explaining how the coronavirus outbreak and consequent layoffs have led to a historically high number of Unemployment Insurance claims, with almost 3.3 million workers making UI claims the week of March 15–21. That is approximately 2.6 million more than the previous record of 695,000 claims in one week.