This essay is part of Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy, a compilation of 10 essays from leading economic thinkers who explore alternative policies for boosting wages and living standards, rooted in different structures that contribute to stagnant and unequal wages. The authors in the new book demonstrate that efforts to improve workers’ access to good jobs do not need to be limited to traditional labor policy. Policies relating to macroeconomics, to social services, and to market concentration also have direct relevance to wage levels and inequality, and can be useful tools for addressing them.

To read more about Boosting Wages for U.S. Workers in the New Economy 20 and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

The exercise of American Indian tribal sovereignty over the past 30 years resulted in more economic growth and improved well-being for American Indians than during any other point in the more than 500-year history post-contact with European colonists and settlers. Increased self-governance over tribal lands and resources created new economic and employment opportunities for American Indians and for non-American-Indians on or near tribal lands and resources as well.1

These advances are the foundation upon which policymakers can build to develop policies to address persistent earnings and income inequality faced by American Indian workers and their families. Even though American Indians are a relatively small proportion of the United States as a whole, in certain jurisdictions, they comprise a relatively large proportion of the population. In states such as Oklahoma, New Mexico, South Dakota, Montana, North Dakota, and Arizona, the American Indian population ranges from 5 percent to 13 percent of these states’ populations. Some tribal governments control (relatively) large amounts of land areas in these states, which should result in meaningful influence over the demand and supply of labor and job creation in these states.

But, as this essay details, large hurdles remain before American Indian tribal governments can fully realize their economic and political opportunities to provide full employment (through public or private enterprises) for their citizens. Significant reductions in family poverty rates and unemployment rates almost doubled real per capita income between 1990 and 2015, yet still-significant income gaps remain, largely because American Indians residing on reservations are less likely to be employed full time than their White counterparts. After detailing these findings—presented against the backdrop of the recent gains in tribal self-governance—I conclude with a look at three areas that hold the most promise for improving earnings and employment for the American Indian population on reservation lands:

- Support tribal sovereignty and industry innovation

- Reduce barriers to economic development

- Improve data collection for American Indians

While not all of these recommendations detailed below focus directly on individual American Indian workers, their families, or their employers, they are important in stimulating economic development and eliminating existing obstacles in and around tribal lands. This economic development and the well-being of American Indians are not only important in their own right but are also key to greater economic growth in these mostly rural and underdeveloped regions of the United States.

The problem: Economic and labor conditions of American Indian workers and their families

There is surprisingly very little research on the determinants of earnings and wage growth for Indigenous peoples in the United States. The vast majority of existing research focuses on the American Indian reservation-based population, which is what I focus on in this essay, excluding the urban American Indian population in my analysis.2 Nonetheless, systematic analysis and evaluation of policies intending to improve the earnings and employment opportunities of American Indians are few and far between.3 Existing longitudinal datasets often do not have a sufficient number of American Indians in order to conduct the standard analyses employed for other races or ethnic groups around the nation.

As a result, researchers do not have the rigorous set of studies over time for these populations. Therefore, there are many opportunities for future researchers to expand upon this report and investigate determinants of earnings growth and employment growth for the American Indian population. Identifying policy solutions to improve the earnings and employment of American Indians is not a trivial task.

First of all, there is little rigorous evaluation of labor force training programs or policies available, compared to other race and ethnic groups in the United States. Additionally, data for this group are notoriously difficult to come by due to the small proportion of American Indians in the overall U.S. population. Still, there are some broad datasets that enable researchers to present a broad picture of the economic conditions of American Indian individuals and their families.

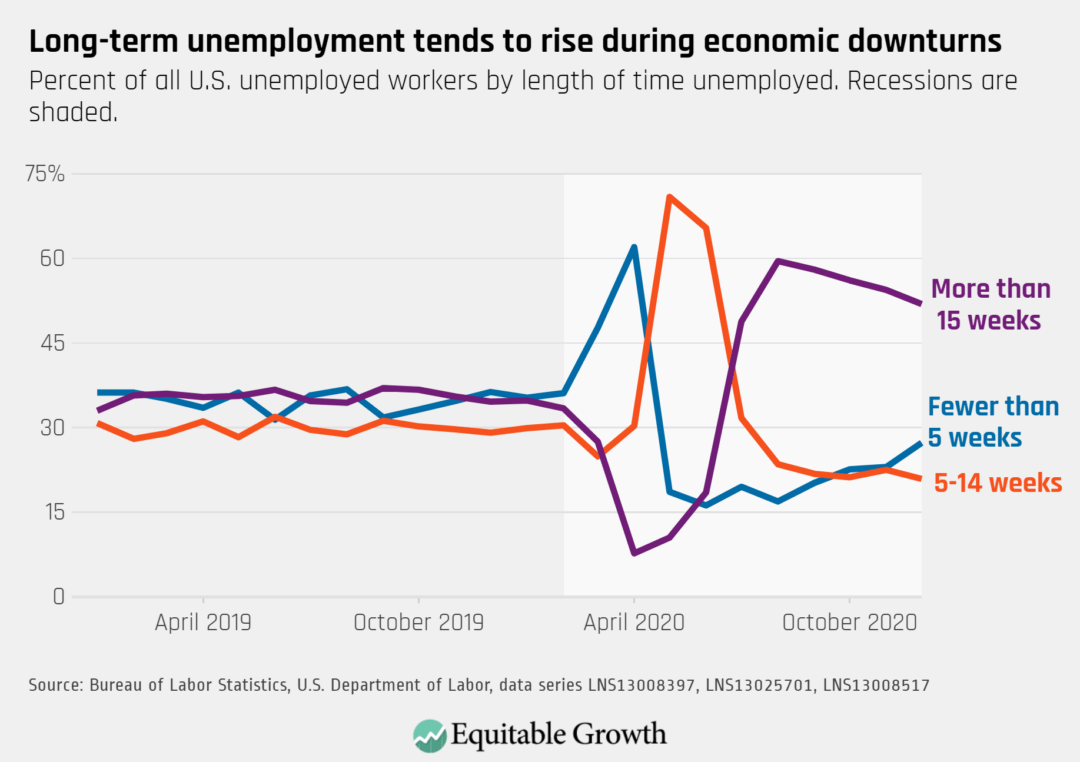

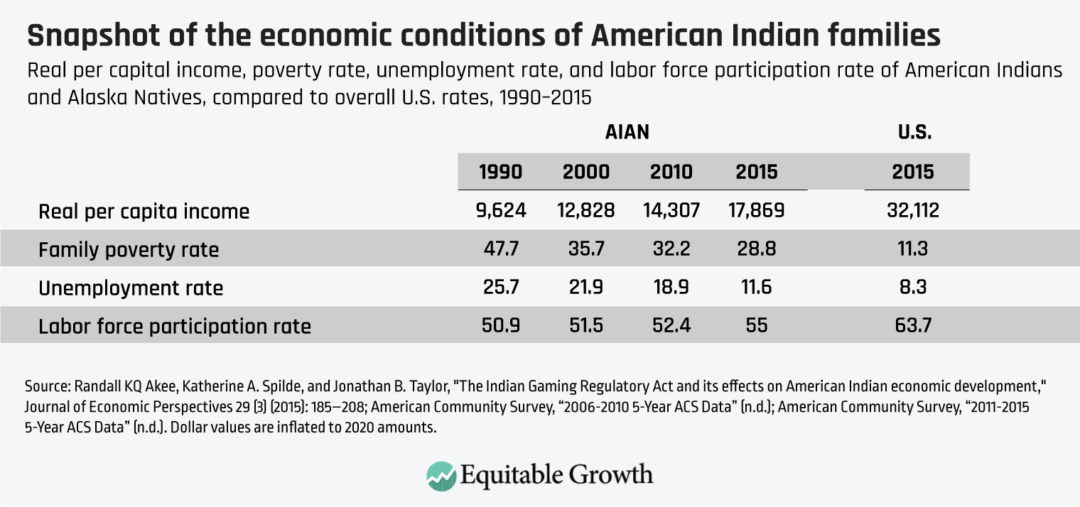

Economic conditions for American Indians residing on tribal reservations are often depicted as dire. In fact, conditions are quite variable, depending upon the tribe and the time period examined. There are 324 reservations or joint-use areas—areas where multiple American Indian reservation governments share legal and political jurisdictions—in the lower 48 states, with wide geographic, regional, and economic variations. Yet despite improvements, family poverty rates, unemployment rates, and labor force participation rates for American Indians are substantially higher, compared to the United States as a whole.

The average poverty rate for American Indians (including Alaska Natives and American Indians living outside of tribal reservations) in 2015, the most recent year for which complete data are available, was 28.8 percent; the unemployment rate in 2015 was 11.6 percent; and the labor force participation rate was 55 percent. All of these rates are generally worse than the United States as a whole, even though economic conditions have improved for American Indians since 1990. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Recent research shows that income inequality also increased in recent decades for American Indians, as is the case for the United States as a whole.4 Measures such as income mobility, or the ability to move up and down the income distribution, stagnated in recent years for American Indians.5

American Indian families also possess little wealth, though relatively little is known about asset ownership across the American Indian population as a whole. One perhaps indicative study of two tribes in Tulsa, Oklahoma, however, finds that the total net worth of American Indian families enrolled in the Cherokee and Muscogee Creek tribes stood at 85 percent and 25 percent, respectively, of the net worth of White families in areas nearby their reservations.6 Examining only home ownership, Richard Todd and Federico Burlon at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis find that home ownership rates for American Indian families overall stood at 56 percent, compared to 71 percent for White families, in 2006, according to the U.S. American Community Survey.7

How work, wages, and incomes of American Indians intersect with state and federal governments

American Indians and other Indigenous peoples in the United States occupy a fairly unique space. They are both a racial group and a political group. The U.S. Constitution and several U.S. Supreme Court cases have determined that Indigenous peoples and governments in the United States are domestic-dependent nations. These populations possess rights that extend to self-governance, exercise of treaty rights, and other laws specific to their political status. These are unique tools and opportunities available for American Indians for creating jobs and boosting wages and incomes.

Historically, the federal government maintained significant control over American Indians residing on reservations. Until they were granted U.S. citizenship in 1924 under the Snyder Act, American Indians were required to get the approval of the federal agent from the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs before they were allowed to leave their reservations. In subsequent decades, the federal government enacted additional policies for this population. One was the urban relocation program, which aimed to create incentives for mostly rural American Indians to seek employment in urban centers such as Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Seattle, and Chicago. The program resulted in the relocation of tens of thousands of American Indians from rural to urban populations between 1950 and 1970.

A second program implemented during this time aimed to completely assimilate American Indians by terminating their tribal statuses as political entities. The so-called Indian Termination era—1940 to the 1960s—aimed to pay American Indian tribes to accept a settlement of money in exchange for the termination of their political status for themselves and their descendants. Researchers have yet to evaluate the impact of these two programs on the well-being, earnings, and employment of these relocated American Indian families and their descendants. Anecdotally, however, there do not appear be any marked improvements, as many American Indians in these urban settings are living in poverty.8

More recently, the federal government took a different approach. It allowed and encouraged tribal governments to expand economic and political control over their jurisdictions and resources. The modern-day federal-tribal relationship is known as the self-determination era and is marked by the expansion of tribal governments into business operations and in the direct provision of government services.

Previously, for example, the federal government would administer programs on the reservations, from schools to health clinics to housing programs. In the self-determination era, under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, tribal governments increased their administration of these programs through direct funding from the federal government, which opened up employment and service opportunities to tribal citizens.

In addition, the passage of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988 provided a unique opportunity for American Indian tribal governments to expand into the gaming industries. As a result, tribal governments expanded their economic development activities into this new area on their own terms over the decades of the 1990s and 2000s. Assessing how these new efforts by tribal governments to boost employment, wages, and human capital investments is the first step toward formulating new policy proposals to address the still-deep economic inequality faced by American Indian workers and families living on reservations across the United States.

Jobs and wages in and around tribal reservations

The basic employment and earnings data for American Indians in the United States as a whole and among those residing on American Indian reservations indicates overall that labor force participation and real per capita income for American Indians increased over the past 30 years. What’s more, the earnings growth for American Indians broadly kept pace with White Americans over this same time period. There are level differences in earnings, however, that persist—even after accounting for some basic human capital and demographic characteristics between these groups over time. And there are stark differences in the earnings of full-time versus part-time workers for American Indians, too.

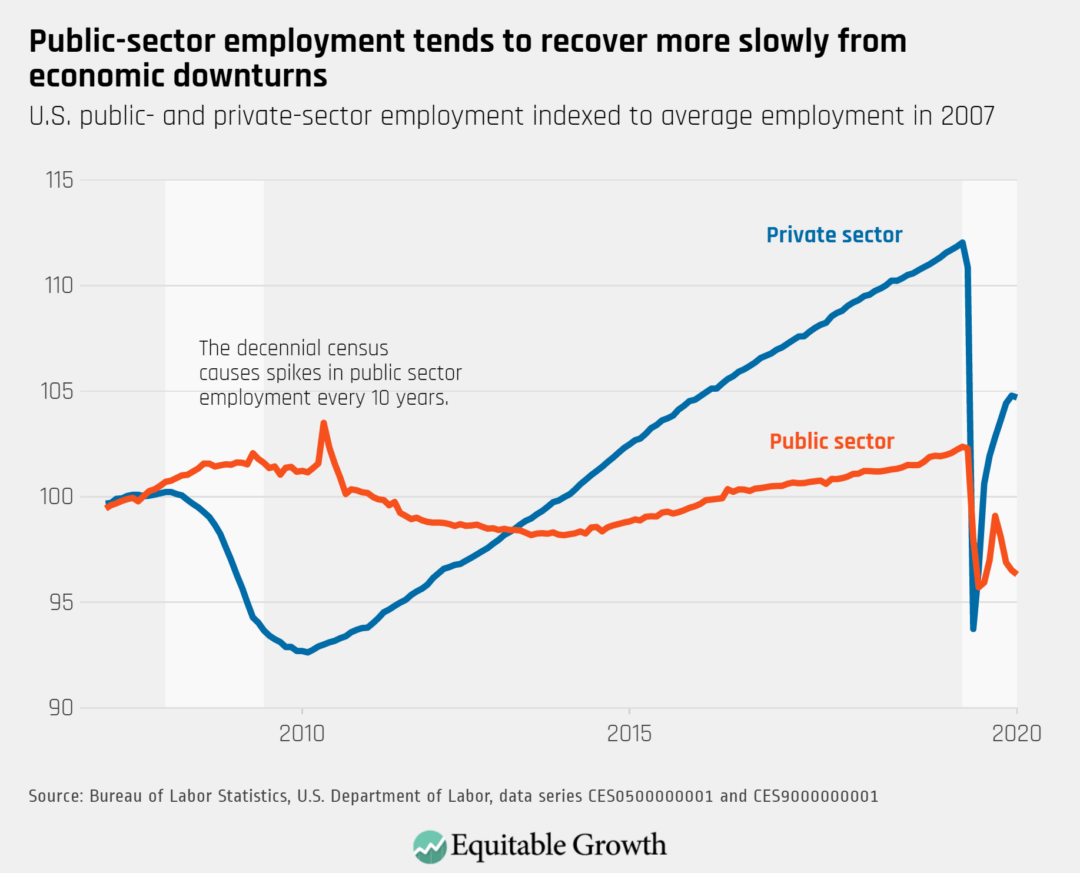

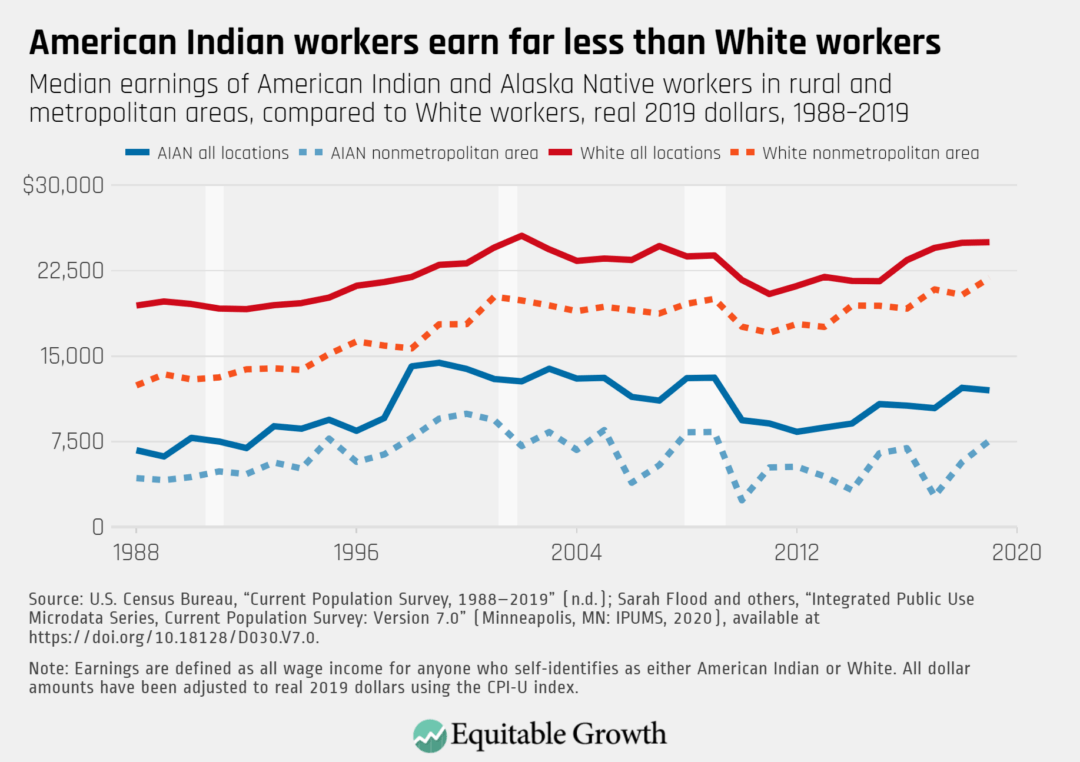

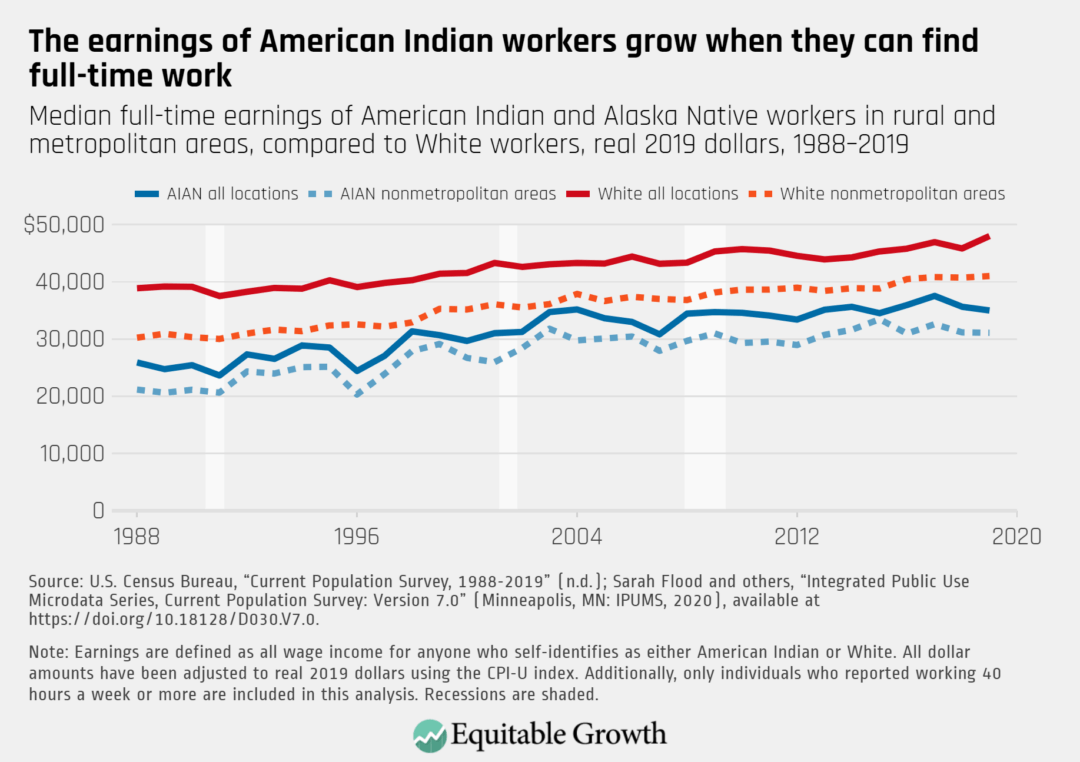

Consider first the median earnings of American Indians and non-American-Indians for the country as a whole and for nonmetropolitan areas as a proxy for reservation locations from 1988–2019. The median earnings of American Indians are indeed lower than those of White Americans for the country as a whole, as well as for the nonmetropolitan/reservation locations.9 The median earnings of American Indians did post a pronounced increase in 1998, but then flatlined before declining amid the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and in the subsequent slow recovery. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

But there is another measure over the same time period that is useful for understanding the median wages of American Indians—those who are full-time employees working 40 hours per week or more. Earnings for full-time American Indian workers and White workers increased for both groups by about $20,000—though full-time employment, on average, accounts for approximately 57 percent of White employment but only 49 percent for American Indian workers. And there was an upward trend in real earnings for all race groups and for all locations. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Some of this upward trend in earnings, however could be due to differences in educational attainment, age, and gender in addition to full-time status. Preliminary analysis suggests that there is a persistent difference between White and American Indian workers for all locations, even after controlling for these important human capital and demographic characteristics.

The upshot: Earnings among American Indian workers residing on reservations are persistently lower than that of White workers in the United States, particularly those American Indian workers who are employed full time, despite some specific economic gains detailed above.

Employment opportunities in and around tribal reservations

Increasing full-time employment opportunities, then, could well be an important way to increase earnings for American Indian workers. And indeed, one measure of job opportunities on and off reservations demonstrates there are ways to lift employment, and thus the wages and incomes, of American Indians.

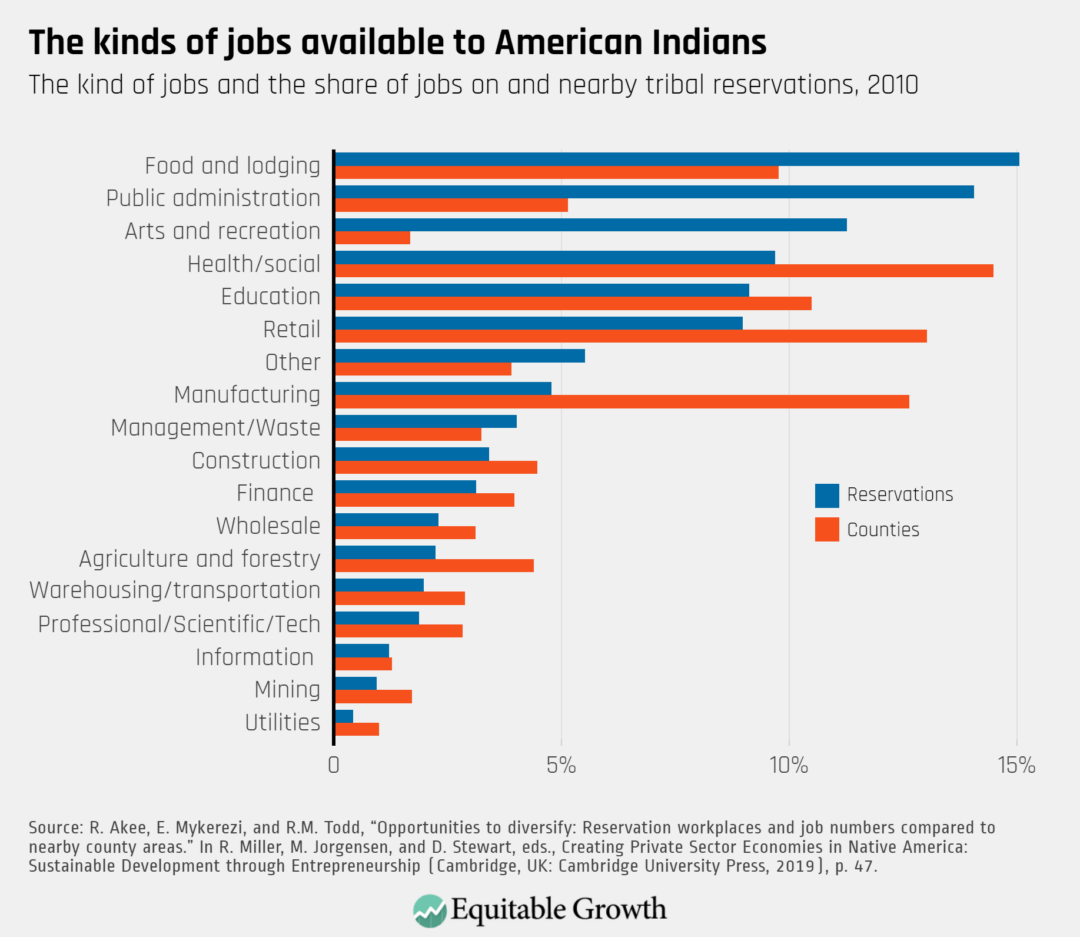

Specifically, there is a large share of jobs on reservations (relative to off-reservation locations) in the following industrial categories: arts and recreation, accommodations and food services, and public administration, according to the Longitudinal Business dataset. These align with the relatively large gaming, tourism, and public administration activities on tribal lands. In contrast, there are relatively fewer jobs on reservations (compared to off-reservation locations) in agriculture, construction, manufacturing, retail, and health services.10 (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

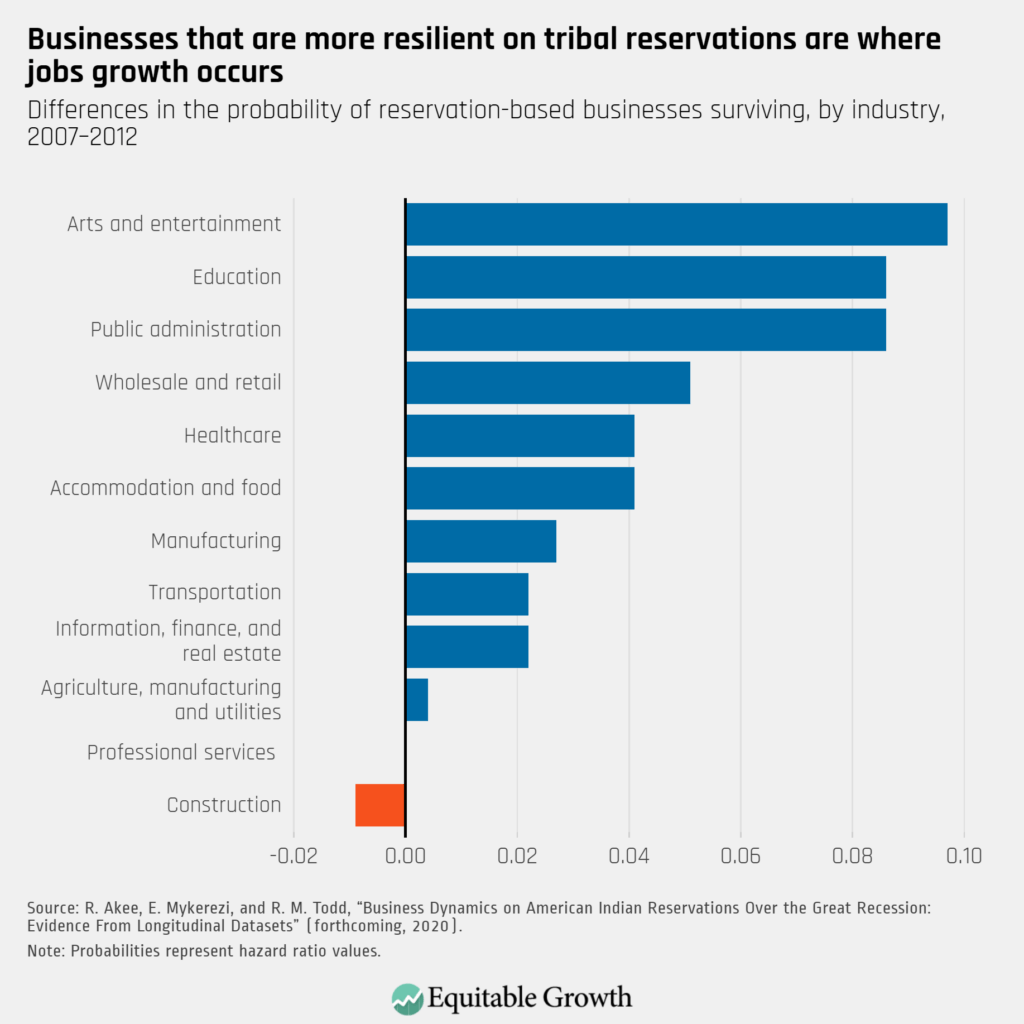

But how many businesses survive in and around tribal reservations? It’s important to assess and understand where policies can drive job creation. The data show, perhaps surprisingly, that reservation-based business establishments during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 were more resilient than in adjacent counties. In particular, establishments in the arts and entertainment, education, accommodations and food services, public administration, and wholesale/retail sectors fared quite well.11 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

One potential reason for more successful businesses on tribal reservations may well be that many of these establishments are also tribally owned and operated. Thus, they may have been maximizing the employment of tribal citizens and local residents over profits during the Great Recession. As a result, they may have made different business decisions than private business owners might embrace. This is one of several findings that inform the policy solutions presented next in this essay.

Solutions to improve earnings and employment in American Indian communities

The data analysis above helps identify potential pathways to encourage and support earnings and employment for American Indians residing on tribal reservations. In this section, I will detail three broad policy proposals that could strengthen the overall conditions for improving employment and earnings on American Indian reservations. Specifically, policies that:

- Support industry innovation and tribal sovereignty to boost jobs growth and wage gains

- Reduce barriers to economic development to spur more job-creation and nonwage income

- Improve data quality and collection to improve economic program and policy evaluation

Let’s consider each in turn.

Support industry innovation and tribal sovereignty

Supporting the full exercise of tribal sovereignty over land, resources, and citizens is an important step in improving the economic conditions of American Indians residing on reservation lands. Under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, tribal governments could apply to take over housing, education, healthcare, and the management of tribal lands themselves. The federal government provided funding for this, and the tribal government hired and managed the employees.

Tribal governments consequently became more responsive to the needs of their tribal communities and were able to hold employees responsible for their actions. Employees had a greater incentive to do their jobs effectively, too. The quantity and the price of tribal timber resources, for example, increased once tribes took control of their timber resources from the federal agencies.12 Similar changes occurred in other agencies; however, rigorous evaluations of those effects in housing, healthcare, and education require better data collection.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 established the requirements for tribal governments to pursue gaming operations on their tribal lands. As a result, gaming operations expanded tremendously throughout American Indian reservations in the 1990s and 2000s. Not all tribal reservations benefited equally from tribal gaming operations, but a large proportion have done quite well. Tribal gaming revenues increased from zero to almost $30 billion annually by 2015, the most recent year for which complete data are available, compared to commercial, non-American-Indian gaming industry earnings of approximately $38 billion.13

Tribal gaming revenues are used to augment existing funding for programs, employment, and service delivery to tribal members. There is some evidence that tribal casino operations also have positive spillover effects to neighboring communities by providing employment options and demand for small business services.14 The gaming industries and provision of federal government services by tribal nations are two examples of tribal nations exercising their own sovereignty and authority in new economic endeavors. They serve as guideposts for future innovation by tribal governments.

Create new innovative industries

New policies, for example, could encourage the funding of new and innovative economic activities that further strengthen and diversify tribal economies in sustainable ways. Expansion into novel industries such as climate mitigation and renewable energy generation would reinforce existing aims and goals of tribal governments while diversifying the economic base in tribal reservations. And expanding tribal jurisdiction and ownership of reservation lands would improve the ability of tribal governments to enact economic development projects on larger scales that may be necessary for nonmarket-based economic activities.

Given centuries of the taking of tribal lands, a concerted effort to restore and increase existing land bases would provide tribal governments with the resources to improve employment and earnings opportunities. This would include efforts to reduce the fractionated ownership of tribal and individual American Indian lands. Additionally, it would provide tribal citizens, potentially, with the option to earn a living in the nonmarket economy through traditional subsistence activities, which is an often-cited desire of tribal citizens.

These policy ideas are already being tested. In Washington state, the Lummi tribe recently created the first tribally owned commercial wetland-mitigation bank in the United States. The landbank provides credits for non-American-Indian developers in other parts of the region that create unavoidable adverse impacts to the aquatic environment from permitted projects. It is an offset program that puts specific areas on the Lummi reservation in perpetual conservation mode. The non-American-Indian developers are required to provide or pay for these credits under several environmental laws. The tribal government earns a significant amount of revenue from this activity annually, and it uses those funds to hire and train wildlife biologists, conservation technicians, and flood specialists. Tribal members are often trained on the job, as well as provided scholarships for college and graduate school to specialize in these occupations. As a result, the labor force has expanded and diversified dramatically.

Similarly, the Yakama, Umatilla, Nez Perce, and Warm Springs Tribes formed the Columbia River Inter- Tribal Fish Commission to improve salmon spawning to the upper regions of the Columbia River. After decades of blockages due to dams, the commission advocated for fish passes at existing dams, as well as negotiated the return of water to some of the smaller tributaries of the Columbia River so that salmon are able to spawn well into Idaho on Nez Perce lands. These results significantly increased the availability of salmon resources inland and provided a return to a traditional way of life and diet for many people. Additionally, fishing revenues for tribal members have increased twofold as a steadier supply of salmon made it more lucrative to specialize in salmon fishing and selling.

Emerging opportunities—such as the 2020 Supreme Court decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma, which reaffirms the jurisdiction of the Muscogee Creek lands in the state of Oklahoma—should be viewed as an opportunity to improve economic conditions for the Muscogee Creek and their neighbors. Indeed, this decision may have lasting implications for other Oklahoma tribes and reservation lands. The ruling re-emphasizes the importance of existing treaties that delineate tribal authority and resources; many of these treaties have been ignored or unenforced for generations.

These types of policy solutions could include a new funding mechanism through the Bureau of Indian Affairs that specifically encourages diversifying economic activities on reservation lands. Awards could be selected in a “race to the top” program, where the most innovative and implementable projects are awarded and serve as an example for other communities and tribal governments.

Tribal tax-exempt bonds could supplement these novel activities. Tribal governments have the authority to issue these bonds, but recent data indicate that only 17 percent of tribal governments have used this method to finance investment opportunities.15 These types of bond issuances are the same ones used by municipal governments for local infrastructure investments and economic development activities all across the United States—they should be encouraged by other tribal nations as an extension of their sovereignty and an opportunity to develop novel industries on reservation lands.

Enact a tribal jobs guarantee program

Given the high levels of poverty and unemployment, on average, on American Indian reservations, a federal jobs guarantee for tribal citizens and residents would provide an important mechanism to improve earnings on reservations. There is significant justification for this program, given the high levels of existing unemployment and the additional impact of the coronavirus pandemic on employment.

The jobs needed should be determined at the tribal level, with the flexibility to adjust employment decisions to strengthen tribal sovereignty and long-run economic development planning for new and innovative industry development on tribal lands. A tribal jobs guarantee program alsowould align employment activities with large-scale climate mitigation efforts and/or ecosystem restoration efforts in tribal nations. Further, the jobs guarantee could also focus on other areas where there are well-identified deficits in service or program provision such as healthcare services.

An ancillary policy reform to encourage jobs growth would be to encourage the adoption of uniform commercial codes on American Indian reservations. These codes allow for a more seamless flow of goods and services across these borders. While all 50 U.S. states have adopted these codes, which facilitate trade in goods and services, not all tribal governments have adopted these codes.16 Taking this step across all tribal reservations would boost jobs.

Restore tribal lands to tribal nation governance

The stealing of Indigenous peoples’ lands is too complex a story to discuss in detail here. Briefly, however, over the centuries, European settler-colonial populations stole, purchased, and seized land from American Indians. Then, during the tribal land allotment era (1887–1934) large parcels of remaining lands were deemed “surplus” by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and often sold at below market value. As a result, almost two-thirds of American Indian-controlled lands, as of 1887, were no longer under tribal or individual American Indian control by 1934.

Efforts to improve the land area controlled by American Indians is an important step toward improving the earnings of American Indians. Today, some American Indian reservations are “checkerboarded” in terms of land ownership, where one square block may be owned by a tribal government or an individual American Indian landowner while the adjacent parcels are held by non-American-Indians. This makes governing difficult, and it makes economic development and investment especially difficult because the parcels may not be large enough to support economies of scale.

As a result, there may be large areas that are not particularly productive because the land use and planning are not well-coordinated. This may also be the case for the preservation of forests, rivers, and lakes. Depending upon the size of parcels, there may be little incentive to protect and preserve large swaths of natural resources.

This, in turn, affects tribal members in a second manner. Tribal lands do not just serve as a place to start a business or to build a home. Reservation lands and the surrounding areas are often protected lands and regions such as forests, mountains, bogs, marshes, bays, lakes, or rivers. Increased access to lands could increase American Indians’ nonwage earnings through hunting, fishing, or gathering. These food resources may be an important component of Indigenous peoples’ diets, depending upon region and time of year.17

Tribal reservations need to be contiguous land to increase the productivity and use of those lands for hunting, fishing, trapping, or other nonmarket-based uses. The U.S. Congress should fund the purchase of reservation lands that have been previously sold to non-American-Indians and expand existing programs such as the tribal land buy-back program, which buys land from tribal members for tribal government use, including the buy-back of nontribal, member-owned reservation lands.18 This would increase the available tribal lands for economic development, land conservation, and nonmarket-based economic activities.

Reduce barriers to economic development

There are significant obstacles to economic development on reservation lands, and tribal nations have taken significant steps to improve those conditions in the past few decades. I briefly describe three specific areas that deserve more attention and are crucial to future economic activities:

- Increase access to capital

- Invest and expand infrastructure on tribal lands

- Boost educational attainment and access

Investments in these three areas would create potential opportunities on tribal lands to increase retail and health services at least to reach parity with that of the adjacent, off-reservation locations and enable the development of agriculture and manufacturing on reservation lands due to the endowment of natural resources.

Increase access to capital

Several of the prior policy proposals refer to programs for tribal governments. Yet access to capital is essential to increase the opportunities for entrepreneurship for individual tribal citizens as well. There are several policy options that would either increase asset ownership or access to credit for tribal members. The first one is to fully fund and extend the Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program administered by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. This program is an important source for home mortgages on American Indian reservations. The expansion of this program has put home ownership in reach for many more American Indians and may serve as an important method to assist in asset ownership for this population.19

A second policy is to boost U.S. Small Business Administration loan guarantee programs, specifically the 7a program, which has been used extensively by American Indian-owned businesses in recent years. It is an important source of capital for business start-up and expansion funds.

A third proposal is to increase the capitalization of American Indian-owned and American Indian-serving Community Development Financial Institutions. In general, CDFIs are regulated by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and were set up in the Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994. They are designed to improve the lending and financial services for underserved people and communities in the United States. Importantly, there is a Native American CDFI Assistance Program that facilitates the Native American-serving CDFIs.20

The demand for credit often exceeds the supply from these CDFIs in and around American Indian reservations. These CDFIs are often composed of American Indian board members and community members who are better equipped to assess and conduct business with this population. These CDFIs increased their lending over the past decade where little to none had previously existed, and the number of Native American-serving CDFIs grew from just 14 in 2001 to 74 by 2016.21 More funding from the U.S. Congress to expand the capital and lending power of these institutions would be money well-invested.

Invest and expand infrastructure on tribal lands

Increasing investment in infrastructure on American Indian reservations is an important means to improving access to employment and educational opportunities. There are two policies that can significantly upgrade or establish different types of infrastructure on tribal lands—improve the physical infrastructure on reservation lands and increase broadband access in rural and reservation communities.

Roads on reservations are often poorly maintained due to a lack of resources. They are often unpaved or severely potholed. Poorly maintained roads impede travel to and from schools, health clinics, and employment. These have long-term effects on the ability to live and work on or off of a tribal reservation.22 Even worse, housing on tribal lands have some of the highest levels of incomplete plumbing and kitchen facilities.23 Tribal homes have a higher likelihood of using wood or coal to heat homes in the wintertime, which often contributes to considerable respiratory illnesses affecting school attendance and employment. Appropriations for the creation and maintenance of tribal infrastructure come from the U.S. Congress. These appropriations are often based on existing treaties and agreements with tribal governments. These responsibilities should be honored by the U.S. government.

Second, there is an increasing need for increasing broadband access in rural and reservation communities. Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, internet access on reservations was low, compared to the United States as a whole, with about 61 percent of households on the median reservation with internet access, compared to about 69 percent in adjacent counties.24 Some largely population reservations, however, fall below 55 percent access, such as the Navajo Nation. Broadband and reliable internet connectivity has taken on even more prominence amid the coronavirus pandemic, as many school-age children and college students rely on the web for their current educational pursuits. For some workers, broadband connection has meant that they are able to work from home while shelter-in-place mandates have been implemented.

In the absence of these connections, this would deal a severe blow to the working population and primary school, secondary school, and college students. The U.S. Congress needs to provide additional funding for the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Tribal Broadband program because current funding allocations and plans are not comprehensive and cover only a small proportion of the uncovered tribal rural areas.

Educational attainment and access

An important determinant of earnings is educational attainment and experience. Educational attainment, on average, is lower for American Indians than the average U.S. citizen.25 Additionally, there is evidence that school quality lags behind that of other race and ethnic groups in the United States.26

That’s why Congress should increase federal funding for reservation-based schools and funding for the Bureau of Indian Education as required by dozens of U.S. treaties with American Indian nations. The Bureau of Indian Education is a direct mechanism to improve educational quality and access on reservations, while fully funding existing tribal colleges and universities would improve access to higher education in culturally relevant settings.

Improve data collection for American Indians

A pervasive obstacle to diagnosing and tracking economic development and earnings growth of the American Indian population is the lack of timely and disaggregated data. Due to their relatively small population size in the United States, American Indians comprise anywhere from 1 percent to 2 percent of the U.S. population, depending upon the definition used for “American Indian.” National longitudinal surveys tend to have very few American Indian observations in their samples. As a result, the only reliable data for this population tends to be data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s decennial censuses and the American Community Surveys.

While these two Census Bureau datasets provide useful information about the American Indian population at single points in time, the same individuals are not linked across time or place, and thus make it difficult to evaluate the impact of employment, training, and educational programs aimed at improving economic outcomes or earnings for American Indians. Therefore, there are far fewer credible research findings for this population, which diminishes the opportunities for advocacy and improved policy implementation.

The U.S. Congress should increase funding for the creation of longitudinal datasets focused on the American Indian population. Alternatively, existing surveys such as the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ National Longitudinal Study of Youth could oversample for these populations so that there would be a usable sample population. Additional longitudinal datasets such as the University of Michigan’s Health and Retirement Study could do the same. These efforts would all lead to increased tools for assessment of the earnings and well-being of the American Indian population over time and under different policies and programs.

Conclusion

Improvements since 1990 in the general well-being of American Indians residing on reservations detailed in this essay need to be expanded in three key ways. The first is the support and exercise of tribal sovereignty and the expansion of innovative industries on reservations. The second is to reduce the barriers to economic development on tribal lands and provide funding for educational institutions on tribal reservations to reduce a persistent barrier to the economic development and well-being of American Indian workers and their families. The third is to increase the data collection on the American Indian population in nationally representative datasets. Without these longitudinal datasets, we are unable to conduct the standard evaluation and analysis of existing training or employment programs on the success of American Indians. Investing in these longitudinal datasets will go a long way to improving our ability to assess which programs work and which do not.

—Randall Akee is an associate professor in the Department of Public Policy and American Indian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Acknowledgments