Overview

For centuries, Indigenous communities in the United States have faced devastating poverty. American Indians and Alaska Natives today experience the highest rate of poverty, at 25 percent, of any major racial or ethnic group in the United States.

The current economic hardships faced by AIAN communities can be traced back to centuries of colonization and discriminatory policies, such as the Homestead Act of 1862, which took land and resources away from Indigenous tribes. In recent decades, tribal governments and community organizers have worked to rebuild their populations and promote educational and economic prosperity both on and off reservation lands.

Data on the economic state of American Indians and Alaska Natives across the country is limited, however, making it difficult for researchers and policymakers alike to assess the needs of individual tribes and communities. Additionally, while those living on and off reservation lands may experience similar socioeconomic disparities, they differ when it comes to the barriers they face to building wealth.

Housing on reservation land, for example, is scarce and poor quality, compared to nonreservation rural housing. This means that potential AIAN homeowners trying to purchase a home on tribal land might experience issues with low housing supply and quality, though they do have access to tribal-specific lending options. Yet potential AIAN homeowners looking to purchase homes outside of tribal boundaries might experience a competitive housing market and be excluded from receiving tribal grants and loans, meaning their options for homeownership might be limited.

This issue brief focuses on the unique challenges that face Native Americans trying to build wealth while living on reservations, including the lack of banking accessibility, housing supply, and high-quality jobs. It also covers a series of potential policy solutions to address these challenges and make wealth building more accessible for Native Americans.

But first, we look at the existing data on Native American wealth and what it can tell us about the disparities these communities face in the United States.

What the data say about Native American wealth

The primary source of wealth data in the United States is the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. Although this survey allows respondents to identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, published results from the survey only offer summary data for White, Black, and Hispanic respondents, with all other races and ethnicities included in an “Other” category.

This level of data aggregation reflects the relatively small sample size of the Survey of Consumer Finances, which does not support disclosure of summary statistics for smaller groups. Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and people of two or more races are all included in this aggregate “Other” group, yet the economic experiences and conditions of each population and subpopulation are vastly different—meaning the data for this group have little analytical value.

State and federal statistical agencies are unable to provide disaggregated data on AIAN socioeconomic experiences and challenges, and they primarily cite small sample sizes in government surveys as the reason. One potential solution, put forth by Blythe George, an Equitable Growth grantee and professor at the University of California, Merced, is for state and federal governments to work with tribal leaders to honor tribal sovereignty and build data infrastructure designed to capture vital information about tribal citizens and the state of their reservations.

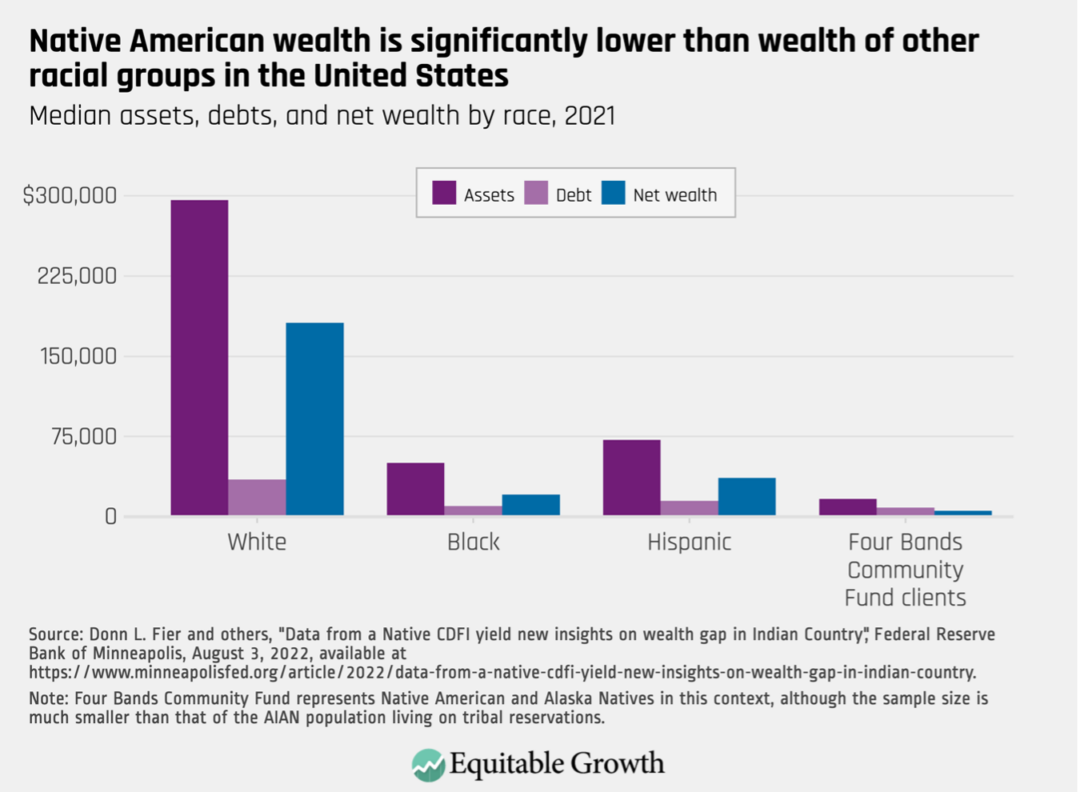

Because these gaps in the data persist, researchers also are looking into alternative metrics that can give some insight into AIAN household wealth. For instance, economists at the Federal Reserve and the Four Bands Community Fund—a community development financial institution, or CDFI, with primarily AIAN clients—looked at the assets and debts held by Native American clients living on the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation in South Dakota. Comparing these data with the wealth metrics in the Survey of Consumer Finances, the study finds that the wealth gap ratio between White Americans and American Indians and Alaska Natives is 32-to-1. The authors also find that while the median net worth of a White household is $181,440, the median net worth of the Four Bands clients is only $5,524. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

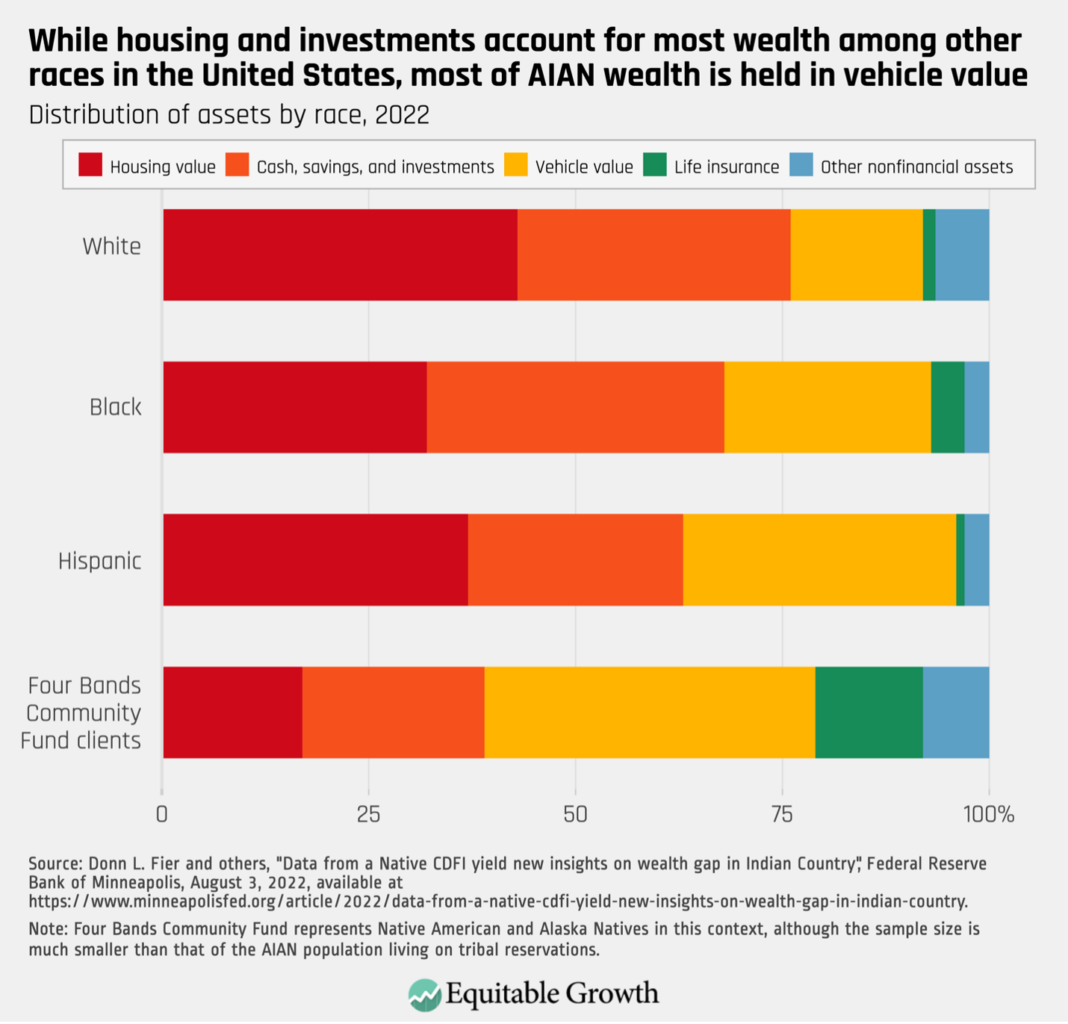

Additionally, while most U.S. households hold their wealth in homeownership, the researchers find that the value of their motor vehicles accounts for the largest component of wealth for AIAN households. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

While these findings are based on a limited sample of Native Americans, they indicate the difficulty that AIAN households have in building wealth.

Next, we turn to the various sources of wealth among U.S. households and the barriers to access that AIAN households face within each specific category.

Barriers to housing and homeownership wealth

Homeownership is the primary source of wealth for most U.S. households. Yet AIAN homeownership rates are considerably lower than White, non-Hispanic homeownership rates, at 50 percent, compared to 71 percent, according to the 2021 American Community Survey.

For Native Americans living on reservation land, homeownership comes with many challenges. Reservations across the country are experiencing a worsening housing crisis due to growing populations, overcrowding, limited supply, and poor-quality housing. Indeed, between 2010 and 2020, the Native American population increased by 160 percent, with a significant portion of this growth taking place on tribal reservations.

Additionally, despite funding and resources from state and federal governments, building housing on tribal land is a complex and expensive matter due to the unique challenges that their geography poses. Reservations in isolated and rural areas or those with limited infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, cannot easily receive the necessary resources to develop housing. In a 2018 U.S. Senate hearing on overcrowding in Alaska Native houses, a regional housing authority official testified that developing housing on Alaskan tribal land is expensive because every piece of hardware and materials must be flown into rural and isolated regions of Alaska.

Systemic discrimination has been a major contributor to the lack of necessary infrastructure on reservation lands. While most state and local governments can use tax-free debt obligations to build public resources, such as roads, parks, and bridges, tribal governments are blocked from using such financing due to The Indian Tribal Government Tax Status Act of 1981. This act limits the use of nontaxable tribal government bonds to “essential government functions,” which does not include road and highway infrastructure.

As part of the Great Recession stimulus package of 2009, however, a pilot program gave federally recognized tribes the authority to issue tax-exempt bonds to incentivize infrastructure development. The program was so successful that the U.S. Treasury Department has since recommended a permanent waiver to the essential government functions mandate to spur social and economic growth on reservation lands.

Because housing is so limited in supply and new housing developments are a rarity on tribal reservations, prospective AIAN homeowners currently face waiting times of 3 or more years for an available housing unit. These long waitlists mean that properties tend to face overcrowding, or situations in which there is more than one person per room in a single housing unit. In 2018, 16 percent of AIAN households on reservations experienced overcrowding, compared to the overall U.S. rate of 2 percent. Some AIAN households even report having 12 to 15 people in units measuring less than 900 square feet.

To make matters worse, many of these overcrowded housing units are low quality. Those living on reservations are “5 times more likely to live in homes that lack basic plumbing, nearly 4 times more likely to live in homes without a sink, range, or refrigerator, and 1,200 times more likely to live in homes with heating issues,” according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Lack of necessary resources, such as plumbing and heating, coupled with the issues posed by overcrowding, can mean AIAN individuals face two related hurdles in their efforts to build wealth: The value of existing properties on reservations is exponentially lower than the U.S. housing market, and resulting health issues from poor-quality housing can prevent AIAN workers from entering laborious, good-paying jobs. During the previously mentioned Senate hearing on overcrowding and its impact on Alaska Natives, witnesses cited research finding that overcrowding causes decreased sleep, increased stress, increased cases of mental health crises, and the elevated spread of illnesses. Likewise, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers from Duke University found that overcrowded housing increases the risk of COVID-19 mortality.

Another element in the reservation housing crisis is the structure of property ownership on reservation lands. In an effort to reduce tribal governments’ control over the land they resided on, President Grover Cleveland signed into law the General Allotment Act of 1887, which allowed the president to “survey Indian tribal land and divide the area into allotments for individual Indians and families” and forced tribal governments to sell any land that exceeded the allotment restrictions to homesteaders or the government. From 1887 to 1934, Native American land ownership plummeted from 138 million acres to just 48 million acres.

Additionally, under the 1887 law, these allotments could be transferred to fee simple land, which gives property owners full rights over their property. Yet this transfer was only allowed on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs. The federal government ended the allotment program in 1934, but even today individuals who own trust land still need to get approval from the agency to sell or develop their land. Having to navigate bureaucratic approval processes means that trust landowners may experience difficulties building or updating housing on their properties, which results in diminished property values.

Barriers to banking and access to capital

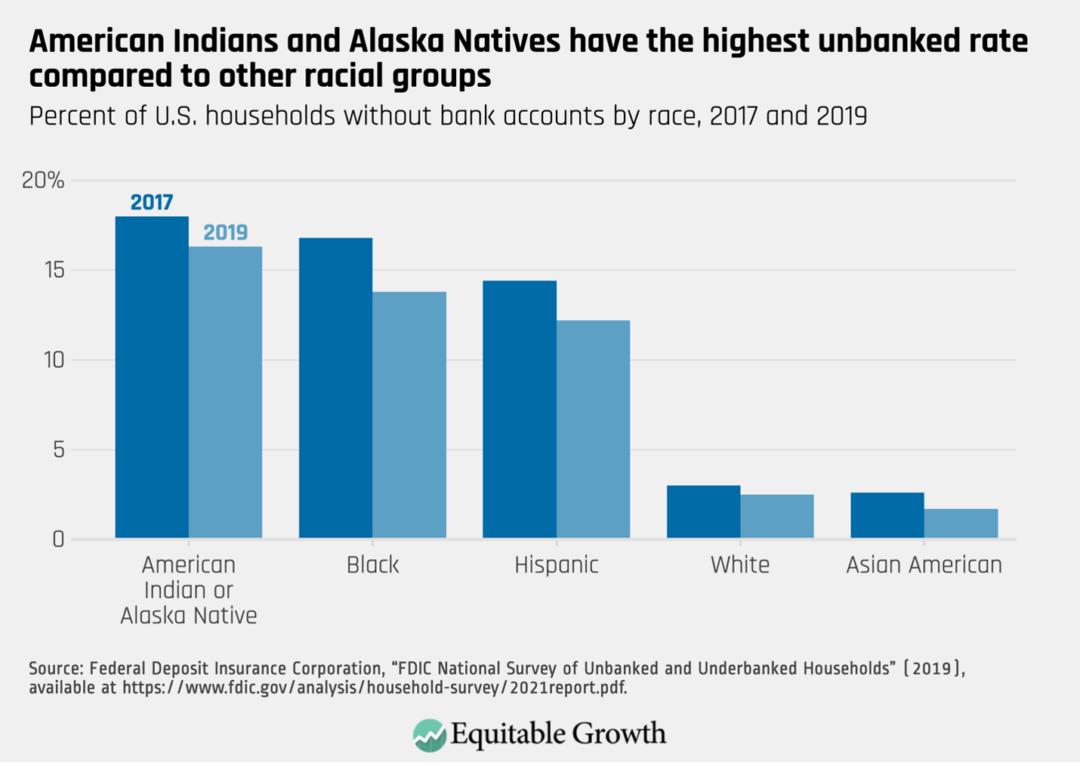

According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Native Americans are the most underbanked racial group in the United States, with approximately 16 percent of AIAN households being unbanked as of 2019. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Of those U.S. households that are banked, AIAN families had the lowest rate of bank branch visits, at 15.5 percent. Physical proximity and general lack of necessary services are the two main reasons AIAN banking rates are so low.

The average distance between Native American reservation lands and the nearest bank is approximately 12.2 miles, almost 20 times the distance between rural city centers and nearby banks. Even if a national bank is within a reasonable distance to tribal land, residents find that such banks neither have an adequate understanding of tribal finances nor provide the necessary financial resources and credit that AIAN households need to navigate investment and housing complexities.

To overcome these challenges, tribal nations have established tribal community banks and CDFIs that support tribal residents as they navigate the nuances of tribal laws and state and federal funding limitations. These financial institutions, often run by tribal nations or tribal entities, provide residents with the tools and services they require to access capital for homeownership or property improvements and other financial needs.

Additionally, researchers find that over the past two decades, Native American Financial Institutions on reservation lands are closing the gap in credit access in tribal regions and providing underserved citizens with much-needed banking resources and knowledge unique to tribal society. Native-owned banks are also seen as more trustworthy and are generally more supported by Native American tribal residents.

Barriers to income growth

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 28.6 percent of AIAN workers were unemployed, a devastating joblessness rate that is only comparable to the general rate of unemployment seen during the Great Depression nearly 100 years ago. Part of this is because Native American workers are often overrepresented in service and front-line occupations, which have experienced long-lasting disruptions since the start of the pandemic.

Yet employment challenges for Native Americans predate the pandemic. In 2020, 21 percent of single-race AIAN people were earning incomes below the federal poverty line due to the many structural barriers to employment—an improvement from almost 29 percent in 2015. Likewise, research from 2013 finds that when controlling for a number of factors, such as age, education, reservation residency, and state of residence, Native Americans had lower odds of gaining employment, compared to White workers.

These findings supplement evidence that almost one-third of Native Americans face racial discrimination when applying for employment or being considered for a promotion, while 54 percent of Native Americans living in areas with a Native majority experience institutional discrimination.

Some researchers point to educational quality and attainment as an explanation for the employment divide between AIAN workers and White workers. A 2018 study on occupational dissimilarities between AIAN and non-Hispanic White workforces, for example, finds that while AIAN workers are overrepresented in low-skilled occupations and underrepresented in high-education occupations, compared to White workers, much of that gap is closed when accounting for differences in educational attainment.

Research also shows that lower educational attainment rates among AIAN students is due to lack of wealth. In 2016, approximately 90 percent of Native American higher education students received some form of grant aid, compared to 77 percent of all students. Another survey on Native American education finds that only 36 percent of Indigenous college students completed their degree within 6 years, compared to 60 percent of all U.S. college students. Participants of the study who did not complete their degree within 6 years cited college affordability as the primary barrier to completing their degree.

Yet differences in educational attainment do not fully explain the workforce gaps between AIAN workers and White workers, suggesting there are other factors that contribute to this occupational sorting. The 2018 study does find that occupational dissimilarities between AIAN men and AIAN women exist, but also finds that when comparing AIAN women to White women and AIAN men to White men, there were not more significant differences in occupational choices than in the comparison of the two racial groups collectively.

Despite these barriers, over the past 30 years, there have been significant improvements in economic well-being among Native Americans living on tribal lands. Randall Akee of the University of California, Los Angeles credits advancements in tribal sovereignty over the past three decades for this economic growth—the best that Native Americans living on tribal land have experienced in the 500 years since contact with European colonists. His research finds that the businesses and industries that survived during the Great Recession of 2007–2009—including arts, entertainment, public administration, food, and lodging—were able to do so because establishments that were tribally owned and operated prioritized maximum employment of tribal citizens and residents over profits.

Policies to reduce barriers to AIAN wealth building

Several options exist for policymakers seeking to reduce the barriers to wealth building for Native Americans, including collecting more and better data, improving physical infrastructure on reservation lands, boosting AIAN homeownership rates, and making banking more accessible for Native Americans, among others. Below, we detail several proposals that policymakers can undertake to boost Native American wealth.

Build better data infrastructure for tribal populations and areas

Before tribal governments can tackle the barriers to building wealth, they need the necessary data to accurately assess the status of wealth and debt held by tribal citizens and residents. The Federal Reserve Board collects information on Native American wealth, but with a limited sample size, it’s difficult to confidently make any statements on AIAN wealth.

Additionally, not all tribes are alike, and their experiences navigating the labor market and the broader economy are different, too. While one tribal government may benefit from comprehensive data on fishing revenue, for example, other tribes may prioritize data on gaming profits.

In a recent phone conversation with UC Merced’s George, she proposed that individual tribes work to build their own data infrastructure that captures their citizens’ unique economic experiences and conditions. Similarly, Desi Small-Rodriguez, an expert in Indigenous data infrastructure and sovereignty at the University of California, Los Angeles, argues that Indigenous people have the most insight into their tribes’ data, and by ensuring their own data sovereignty, tribal governments are able to reclaim their tribal sovereignty.

These tribe-specific data can assist state and local governments with understanding the individual needs of each tribe and creating funding opportunities that tackle the unique problems each tribe faces.

Develop physical infrastructure to boost housing supply on reservation lands

Tribal leaders and policymakers should look toward improving AIAN homeownership to boost Native American wealth. One way to do so is for state and federal governments to establish funding opportunities for tribal governments to incentivize infrastructure development on reservation lands. Better roads, irrigation, and other public-access projects will establish the necessary infrastructure to build higher-quality housing, and more of it.

Similarly, waiving the limitations of the Indian Tribal Government Tax Status Act and issuing tax-exempt bonds to develop roadway infrastructure would make rural and isolated tribal land more accessible, facilitating the delivery of the materials that are essential to housing development.

Establish funding for home upgrades and clean energy retrofits

Research shows that overcrowding and poor housing quality impact tribal residents’ quality of life and employment stability. State and federal funding to help upgrade residences and infrastructure, such as resilient electricity, plumbing, and insulation, can improve home values while also reducing the health risks associated with overcrowding on reservation lands.

The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act allocated funding to tribal nations and Native American communities to support climate resilience and adaptation, build stable clean energy systems, and make home efficiency upgrades cleaner and more affordable. With a reliable energy system and low-cost options for home improvements, AIAN households will have an opportunity to live in safe and high-quality housing.

Improve accessibility to lending and banking

Several federal agencies have launched programs and grants specifically to promote homeownership for AIAN people. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Section 184 Indian Home Loan Guarantee Program gives AIAN borrowers loans with low down payments that can be used to purchase existing homes, construct new homes, or rehabilitate older properties.

The U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Housing Improvement Program also provides grants to AIAN households “who have no immediate resources for standard housing” in an effort to tackle rampant homelessness on tribal land.

Support Native American Financial Institutions

While home loan programs exist to improve AIAN communities’ access to homeownership, many households have difficulty accessing these programs due to limited banking operations on reservation lands.

Federal and state governments can work with tribal authorities to establish and support Native American Financial Institutions or any financial institutions that cater to tribal residents specifically. These specialized banks are generally more trusted than national banks because they educate tribal citizens about the designated government programs for which they are eligible that can help them on their path to homeownership and wealth building. They also tend to have specialized knowledge about the tribes and areas they are serving, which allows them to better serve their communities.

Elevate tribal sovereignty to foster additional labor market growth

Academics studying AIAN labor market barriers all point to tribal sovereignty as the key factor leading to the economic growth on reservation lands since the 1980s. For instance, a 2006 paper on economic development on tribal land finds that when tribal governments have more control over community resources, it positively impacts economic growth.

Similarly, a review of academic literature on Native American credit access finds that while improved educational attainment and market access can improve economic growth, “they tend to pay off after a Native nation has been able to bring decisions with local impact under local control and to structure capable, culturally legitimate institutions of self-government that can make and manage those decisions.”

In his essay for Equitable Growth’s Boosting Wages book, UCLA’s Akee proposes tribal sovereignty and innovation of the industries currently operating on reservations as solutions to improving the employment conditions of Indigenous people living on tribal land. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act of 1988 gave tribal governments the guidelines for developing gaming establishments on tribal land, and since then, the fast-paced boom in tribal gaming operations has been a prosperous endeavor for most tribal communities. In 2015, the tribal gaming industry brought in almost $30 billion in revenue, compared to the nontribal gaming industry’s annual revenue of about $38 billion.

The establishment of tribal sovereignty over the gaming industry is a clear example of how tribal governments’ control over economic regulations directly improves employment and economic conditions of tribal citizens for the better. Building off these successes, Akee’s research finds that federal policies that support industry innovation, restore land bases to tribal governments, and grant authorization to tribal citizens who seek to earn a living through “traditional subsistence activities” can improve employment and earnings opportunities.

As an example, he cites the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, a modern coalition of four tribes dedicated to promoting salmon spawning in the upper regions of the Columbia River. Efforts to improve fish passes at dams along the river and the return of water to smaller offshoots of the river have had positive impacts on the environment, society, and the economy in the region. These changes have restored water and salmon to areas once blocked off through dams, improved the availability of salmon to inland communities, and brought in new fishing revenue to tribal communities.

Conclusion

After centuries of systemic racism and discrimination, Indigenous communities on and off tribal land deserve the right to economic growth and development. Federal and state governments have been working toward this goal through a series of grants, loans, and funding programs that aim to rectify the wrongs committed against Indigenous communities. These programs, in tandem with efforts to boost housing supply and quality and access to banking and financial institutions, will go a long way to reducing the Native American wealth divide in the United States.

Yet academics and advocates find that tribal sovereignty, self-governance, and better data infrastructure also are necessary to further develop economic growth and prosperity for AIAN communities. Expanding upon three decades of tribal sovereignty by introducing tribal data infrastructure can only help AIAN groups understand their unique economic conditions, allowing them to break down the barriers to wealth building and provide sustainable economic growth for all tribal communities.