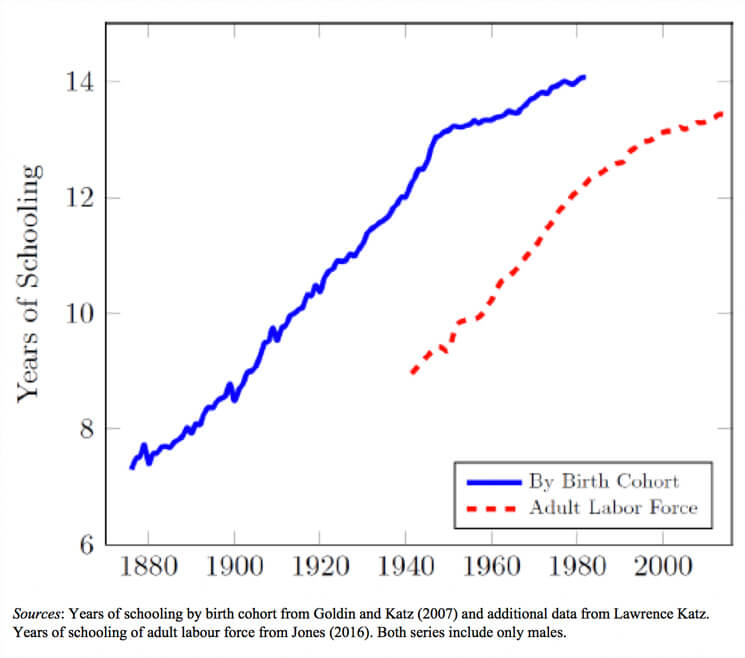

Hiring is difficult these days. But how concerned should policymakers be? Employers in the United States are finding it more and more difficult to fill vacant jobs, as the ratio of hires-to-vacant jobs was 0.9 in January 2018, significantly lower than the average of 1.3 during the previous economic expansion of 2001 to 2007—a difference of more than 1 million newly hired workers. This decline started as the recovery from the Great Recession began—see Figure 1—but is the decline in the ratio (known as the vacancy yield) a sign of a very tight labor market, or are there other forces in the labor market that are causing a decline in the matching of open jobs to willing workers?

Download FileEmployers may be behind the problems with U.S. hiring

Read the full PDF in your browser

Figure 1

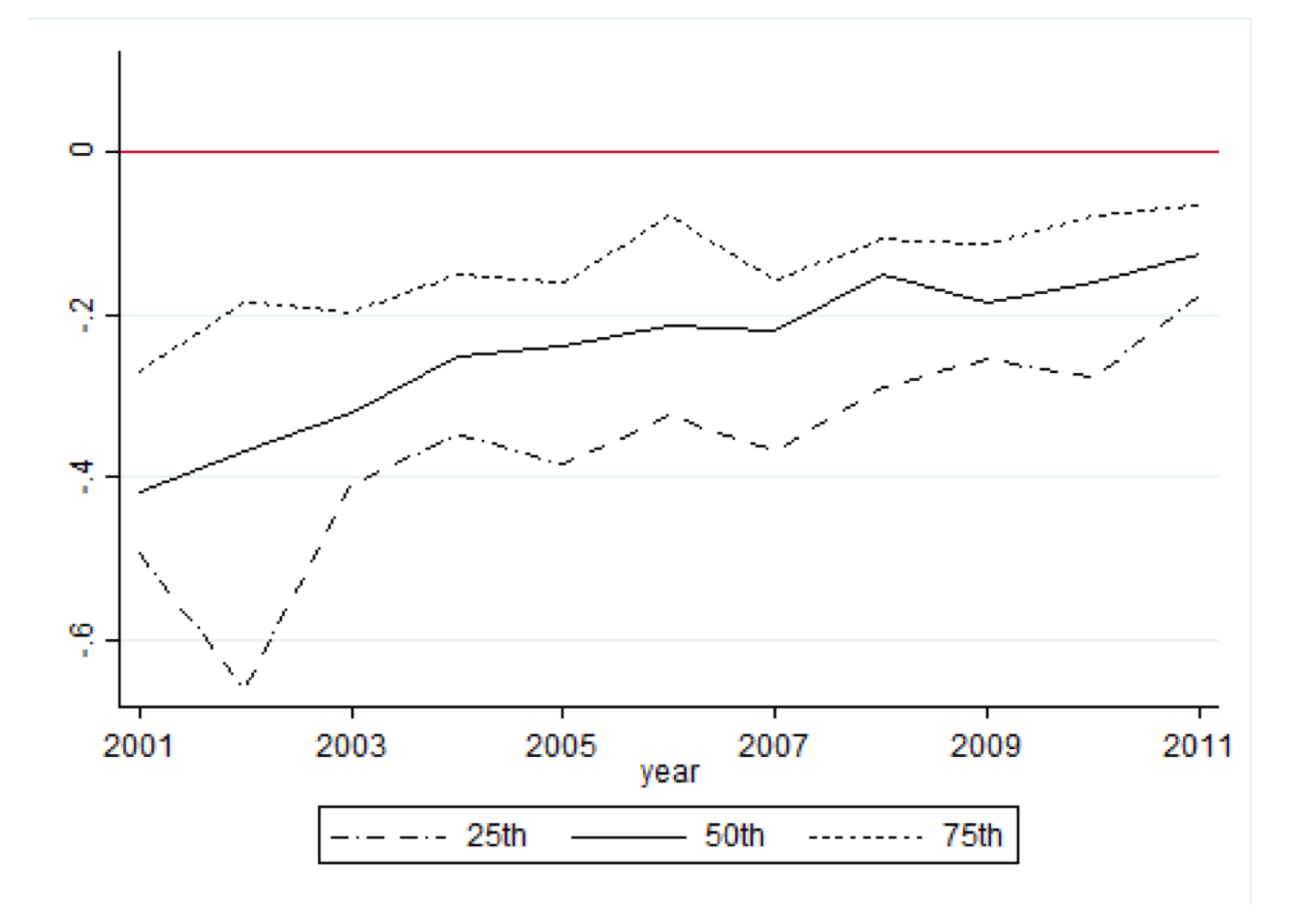

A look at the data on vacant jobs and hiring shows more nuanced developments. The decline of the vacancy yield has been driven by the recovering labor market because the yield is declining as unemployment falls as well. But the vacancy yield has fallen much faster than previous experience would have predicted. Employers are increasingly reticent to hire workers already with a job—a development that is much different from the prevailing explanation that unemployed workers or workers outside of the labor force could not get hired again. In fact, the hiring of workers without jobs is in line with the current strength of the labor market.

The future path of the vacancy yield may continue to decline because the labor market ratio of unemployed workers-to-vacant jobs consistent with strong and sustainable wage growth appears to have declined. To simplify things a bit, employers could be finding it harder to hire new workers because the labor market is getting tighter; workers may be less willing to take jobs; employers may be less willing to increase wages to hire workers; or it could be some combination of the three.

If the decline in the vacancy yield is due entirely to a tightening labor market, then employer complaints about hiring would be mostly a complaint about a labor market heading toward full employment. Employers have a relatively easier time hiring workers when the labor market is weak. They have to spend fewer resources searching, as there are so many workers actively looking for work who will come to the employers. A larger supply of unemployed workers also reduces the bargaining power for each worker, pushing down the starting wage, all things being equal. Both factors make the cost of hiring a worker when the labor market is slack relatively cheap.

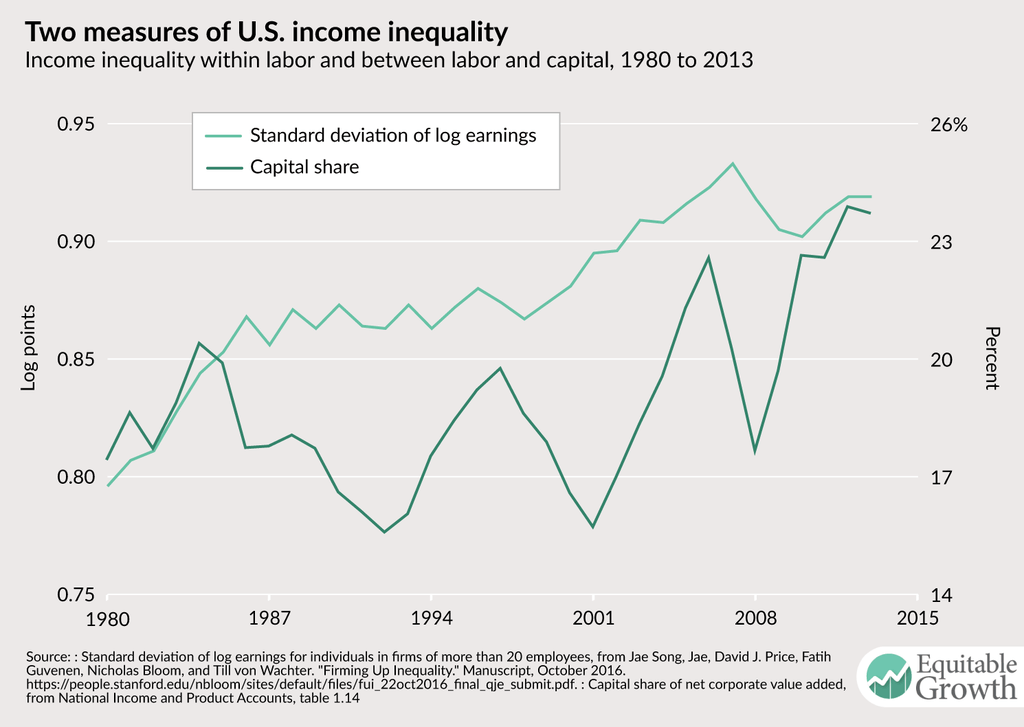

Graphing the vacancy yield against a measure of labor market tightness such as the ratio of unemployed workers-to-job openings would be a quick check of the validity of this cyclical development. A higher ratio indicates a weak labor market with many more unemployed workers per available job, and a lower ratio signals a tighter labor market. Figure 2 uses data from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, from January 2001 to December 2017 to show that the decline in the job vacancy yield doesn’t appear to simply be the result of a tightening labor market.

Figure 2

The data show that the vacancy yield has declined as the labor market tightened, but the decline has been much stronger than just the health of the labor market would have predicted. If the relationship between the vacancy yield and the unemployment ratio from 2001 to 2007 still held, then there would have been roughly 1.1 hires per vacancy in January 2018. Instead, there were only 0.9. That might seem like a small difference, but with 6.3 million job vacancies in January 2018, an increase of 0.2 hires per vacancy would have resulted in 1.2 million more workers hired.

The difficulty in filling jobs is not simply a cyclical phenomenon but may be caused by a change in the “matching efficiency” of employers and employees. Something has changed the rate, given the health of the economy, at which vacant jobs and workers match to create a new hire. One way to see if there’s been a structural change in unemployed workers getting jobs is looking at the Beveridge Curve, which details what the unemployment rate will be for a given amount of job vacancies posted by employers.

Consider the unemployment rate as a measure of labor supply and the vacancy rate as a measure of labor demand. The data on job vacancies come from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics dataset. When the vacancy rate declines—employers are posting fewer jobs—the unemployment rate will increase, as more workers are losing jobs and fewer unemployed workers flow into employment. When employers post more jobs and the vacancy rate increases, the unemployment rate will decline, as more workers flow out of unemployment. The result is that the Beveridge Curve is a downwardly sloping line when the unemployment rate is on the horizontal axis, and the vacancy rate is on the vertical axis. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The current relationship between unemployment and job vacancies appears to be consistent with the curve before the Great Recession of 2007–2009, despite a winding road back. Therefore, a decline in the hiring of unemployed workers is not a candidate for explaining the shift in the vacancy yield.

But if the Beveridge Curve indicates that unemployed workers can just as readily get hired for jobs as in the past, then what explains the structural decline in the vacancy yield? The key distinction here is that newly hired workers who were previously unemployed are only a subset of all hiring. Not all hiring is the result of unemployed workers gaining jobs. New hires also include workers who previously had a job and jobless workers from outside the labor force who don’t register as officially unemployed. The decline in hiring might be broad-based across all these types of new hires or concentrated in one group. Understanding where new hiring declined the most may be helpful in diagnosing the cause.

Unfortunately, the data on hiring in JOLTS do not let economists look at workers’ previous employment situation before they were hired for their new job. Yet there are ways to disaggregate hires using other datasets in order to see what kinds of workers are finding new jobs. In a working paper, economists Peter Diamond at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Ayşegül Şahin at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York use data from the Current Population Survey to break out newly hired workers according to whether they were previously unemployed, employed, or previously not in the labor force.1

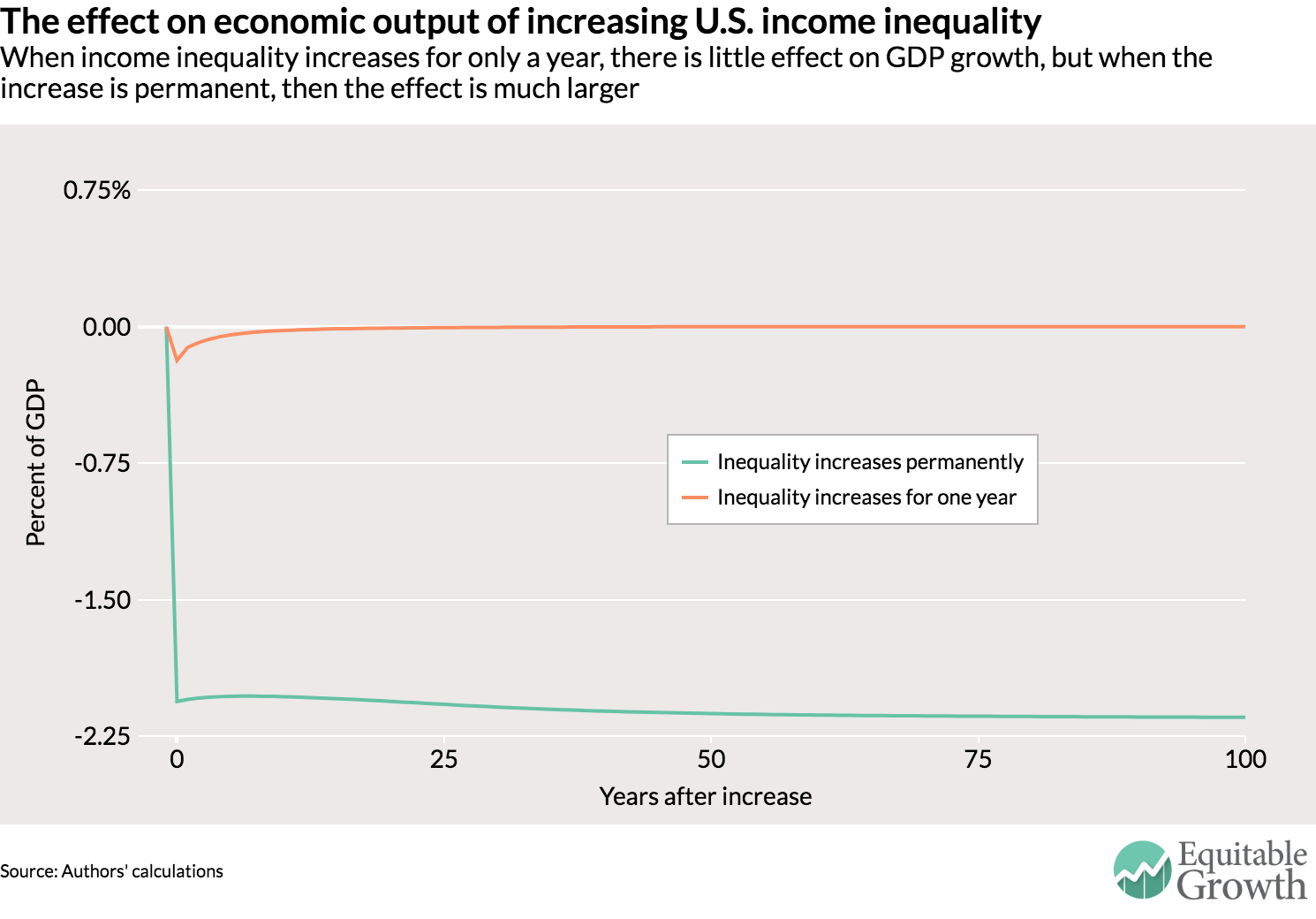

Their results are quite stark. New hires not previously in the labor force during the current recovery are in line with previous recoveries. New hires from the ranks of the unemployed are a bit out of line with previous recoveries, but their data cover only up to the first quarter of 2016. But using the same dataset as Diamond and Sahin, Figure 4 shows that new hires from unemployment are roughly in line with previous recoveries.

Figure 4

But the set of newly hired workers that’s clearly declined is new hires from employment, or job-to-job moves. As the U.S. labor market has tightened, employers are making fewer hires from workers already employed at other firms than during the past recovery. This decline is not just a product of the current recovery. The response of job-to-job hires to labor market tightness during the 2001–2007 recovery was weaker than during the economic recovery before it (from 1991 to 2001), according to Diamond and Sahin’s data. In other words, the structural decline in job-to-job moves is an almost 17-year trend.

What’s behind the decline in the matching efficiency of new hires for already-employed workers? If employers really want to fill vacant jobs with already-employed workers, then the onus is on them—employers need to increase wages in a bid to poach new employees from among the already employed. That development would be evident in the data on wages and wage growth for workers if wages and wage growth were increasing quite a bit as employers fill vacancies. Yet the data on the wage growth experienced by job switchers show the exact opposite.

The Wage Growth Tracker from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta shows the long-term decline in median wage growth for workers who switch jobs. Median wage growth increases as the labor market tightens, but the peak during each subsequent recovery has been lower than the previous high.2 (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

This trend indicates that employers are failing to increase wages or boost wage growth to fill vacancies, which, in turn, is indicative of a decline in matching efficiency on the employer side. Employers may seemingly want to hire but aren’t willing or able to pay the wages to do so. In contrast to complaints about the quality of available workers—the so-called skills gap3—the decline in matching of already-employed workers appears to be driven by changes on the employer side of the bargaining table. Exactly why companies are less willing or able to raise wages in order to poach workers deserves attention from both researchers and policymakers. Jobs aren’t getting filled, and the tightening labor market isn’t entirely behind this situation.

How much lower will the vacancy yield fall?

Given the structural forces pushing down the vacancy yield and an unemployment-to-vacancy ratio near historic lows, has the vacancy yield gotten as low as it can? Put another way: Is the historically low vacancy yield an indication that the U.S. labor market is at full employment? At first blush, there is reason to be skeptical of that claim, given the restrained rate of wage growth in recent years. Other indicators such as the prime-age employment (ages 25 to 54) rate point toward continued labor market slack.4 But returning to the Beveridge Curve, there is some more evidence that the labor market can continue to tighten.

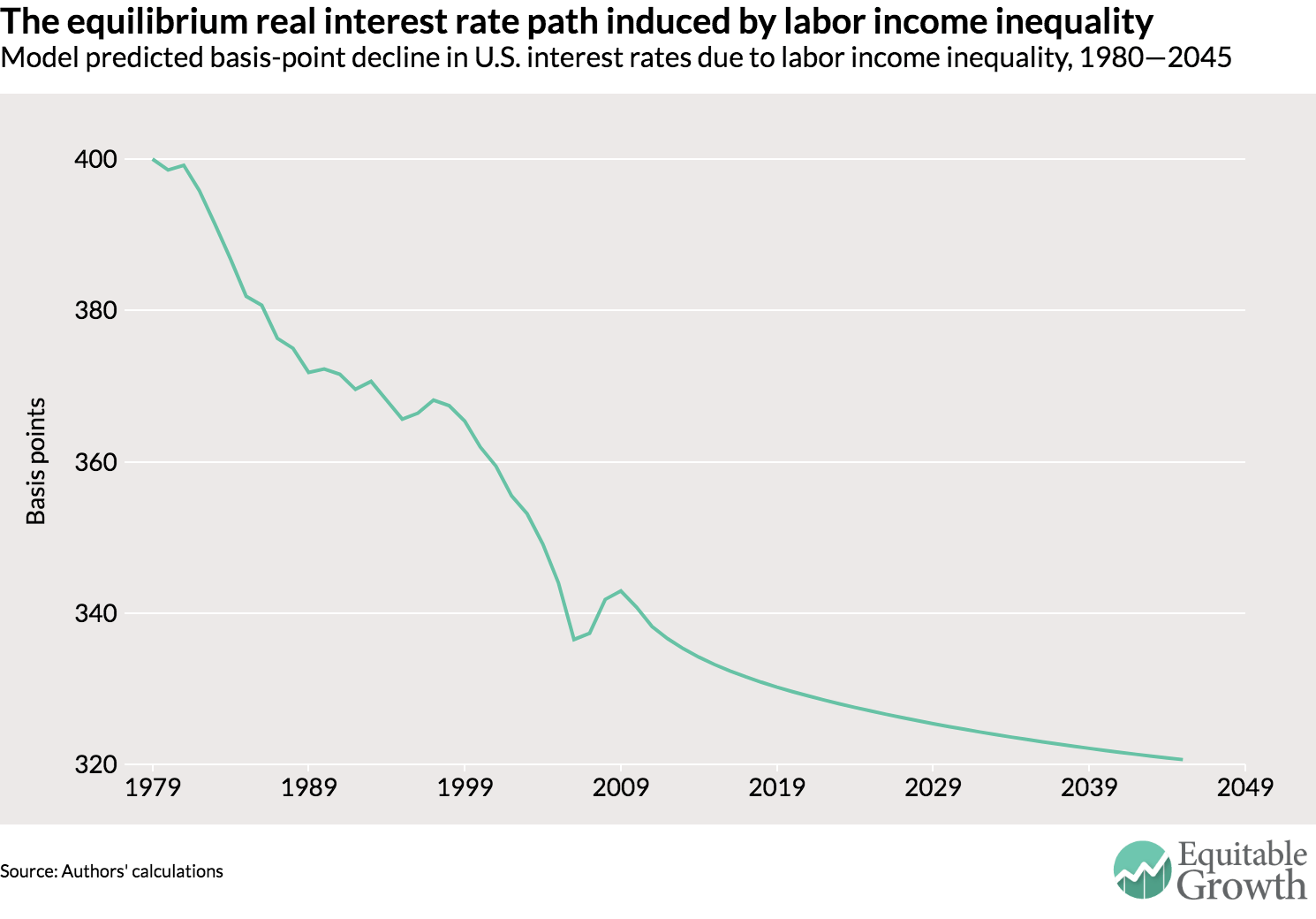

The Beveridge Curve appears to be back in line with its pre-recession trend, which would mean that the unemployment rate for a given job vacancy rate hasn’t changed. Yet there’s also the possibility that the vacancy rate for a given unemployment rate has changed. This relationship is described by the job creation curve, which captures employers’ decisions to post a job vacancy for a given amount of labor supply. When the labor market is weak and there are many unemployed workers, the cost of filling a job is quite low and employers post more vacancies. When the labor market is tight and finding workers is difficult, the cost of filling a job is higher and fewer vacancies will be posted. The job creation curve is therefore upward sloping when the unemployment rate is on the horizontal axis, and the vacancy rate is on the vertical axis. (See Figure 6)

Figure 6

Another way to describe the job creation curve is that employers post more vacancies when they have more bargaining power and post fewer vacancies when they have less power. The economy moves along that line over the course of a business cycle, but structural shifts in the bargaining power of employers or employees could shift the whole line. An increase in worker bargaining power, for example, would shift it down and to the right, while more powerful employers would shift the curve up and to the left.

Economists Andrew Figura and David Ratner at the Federal Reserve Board argue that a structural tilt in bargaining power toward employers has shifted the job creation curve.5 They look at the relationship between the labor share of income—a proxy for employee bargaining power—and the ratio of job vacancies-to-unemployed workers. If the decline in the labor share of income is due to increased employer power, then industries and states that experienced larger declines in labor’s share of income will see a larger increase in the number of vacancies per unemployed worker.

Figura and Ratner find just such relationships in the data and argue this implies the job creation curve has shifted such that today, employers will post more vacancies for a given unemployment rate. With an unchanged Beveridge Curve, a shift in the job creation curve would mean a lower equilibrium unemployment rate, a higher equilibrium job vacancy rate, and a lower equilibrium unemployment-to-vacancy ratio. All three developments would be consistent with a U.S. labor market that has room to run.

If the U.S. labor market is really at this new equilibrium, then the current job vacancy rate might be low by historical levels but still not low enough to be consistent with full employment. The labor market looks to move further down and to the left on Figure 2, which would lead to a continued decline in the vacancy yield. It’s unclear how much further it could go—and it won’t become apparent until wage growth starts to pick up significantly.

Conclusion

The decline in the rate at which vacant jobs posted by employers are turning into hiring of new workers is one part encouraging and one part concerning. The declining vacancy yield is consistent with a tightening labor market. Furthermore, unemployed workers and workers outside of the labor force don’t appear less likely to be hired given the state of the labor market. Yet employers seem less willing to raise wages in order to poach other companies’ employees.

For policymakers, these results have three implications. The first is that the historically low vacancy yield does not necessarily mean the labor market is at full employment. Employers seem more willing to post job vacancies than in the past, meaning the yield can fall much lower without significantly pushing up wage growth. Increasing employer complaints about the difficulty of hiring may be the price of getting the labor market all the way to full employment and strong wage growth.

Secondly, a tighter labor market may not boost the bargaining power of workers as much as in the past. A higher vacancy yield for a given level of labor market tightness tilts the bargaining table toward employers. Policymakers interested in boosting workers’ bargaining power should be aware that structural reforms need to be made in addition to hitting the cyclical goal of full employment.

Finally, employer complaints about being unable to find workers to fill jobs should be taken with a grain of salt. The fact that workers are flowing out of unemployment at rates consistent with past experience in combination with relatively tepid wage growth is an indication that a viable labor supply is available, just perhaps not at the price employers would like to pay in wages. A deeper understanding of the origins of employers’ hesitation to boost wages to poach talent should inform policymakers’ efforts to increase hiring among already-employed workers.