Economic theory tells us that there are benefits to a dynamic labor market in which workers are matched with jobs based on their skills, interests, and ambitions so they can earn wages equivalent to the value they contribute to production. “Job search and matching theory” is a framework economists use to understand the mechanisms underlying the process of workers transitioning between jobs, as well as the obstacles to efficient matching of workers with jobs. Since its inception, the theory has been applied in a variety of contexts, and it is a particularly helpful frame both for understanding how the advent of new job search, matching, and recruitment technologies may influence workers’ job opportunities and for shedding light on how these innovations can be crafted to secure fairness and competition in the U.S. labor market.

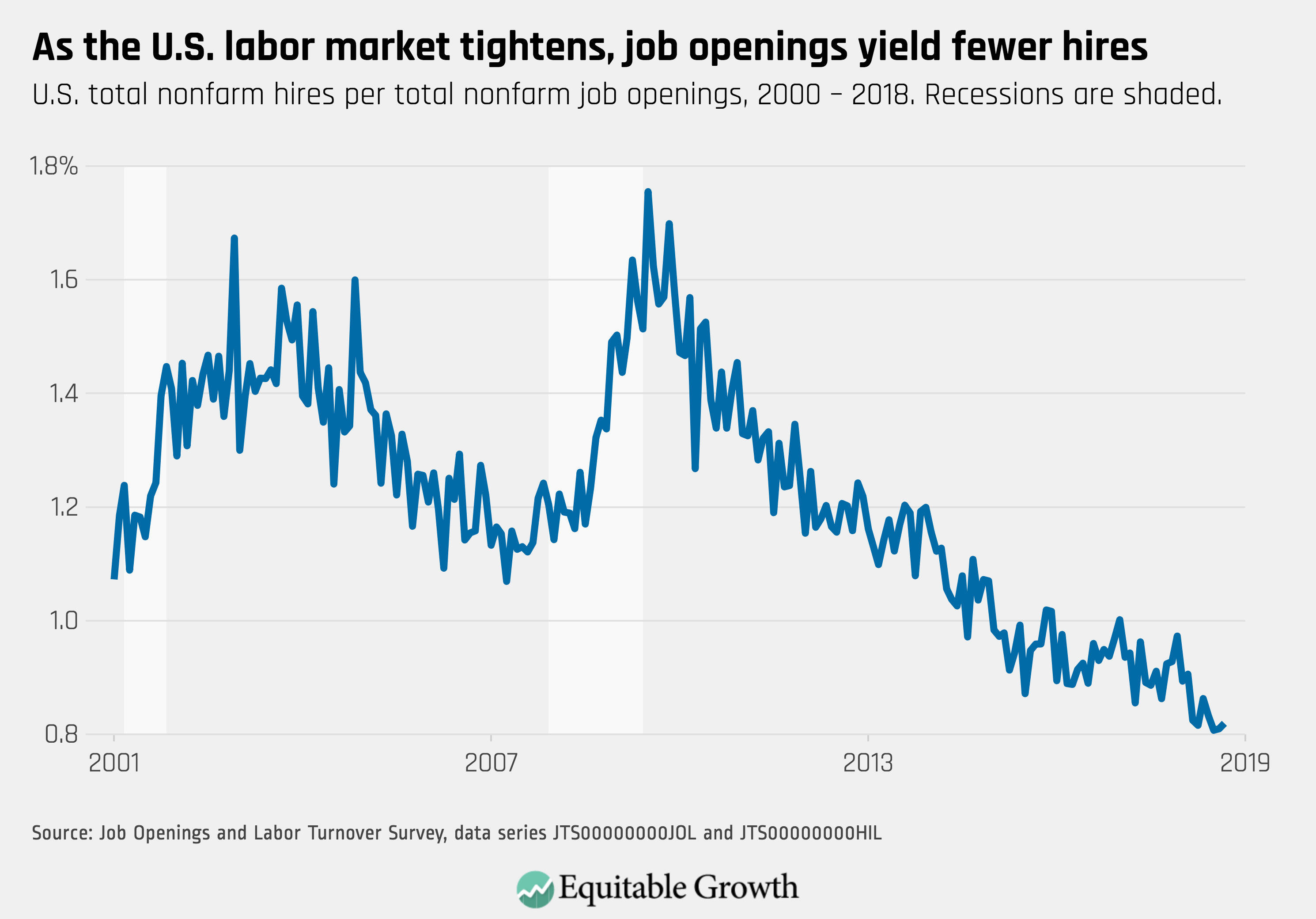

Despite the rise of online job-matching platforms over the past decade, search frictions and skills mismatch continue to be persistent problems for both employers and employees. While new companies such as LinkedIn Corp. and Indeed Inc. have eased the process of identifying vacancies for job-seekers and attracting applicants for employers, online job boards have also created new frictions by proliferating the average number of applications per job-seeker and per job opening. Costs remain particularly high for low-skill, low-wage job-seekers, who are the least likely to have access to and proficiency in new digital technologies and are simultaneously the most likely to spend substantial amounts of time completing numerous burdensome job applications on their smartphones. Among other factors, these search frictions contribute to a persistent skills mismatch between workers and jobs. According to an employer survey by McKinsey & Co Inc., 40 percent reported lack of skills as the primary reason for job vacancies. In contrast, 37 percent of job-seekers in a LinkedIn study said they were underutilizing their skills in their current positions.

The central theoretical model describing the process of looking for and finding a job in the contemporary economics literature is the search and matching model developed by economists Dale Mortensen, formerly of Northwestern University, Christopher Pissarides of the London School of Economics, and Kenneth Burdett of the University of Pennsylvania. Along with economist Peter Diamond at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Mortensen and Pissarides received the Nobel Prize in 2011 for their foundational work with this framework, which describes how search frictions’ lack of information, as well as mismatch between skills and interests offered by workers and wages and benefits provided by jobs, hinder the efficient matching of job-seekers with job openings. These obstacles affect job transitions and depress labor market dynamism, which can lead to prolonged bouts of unemployment, noncompetitive wages and benefits, and stunted productivity growth.

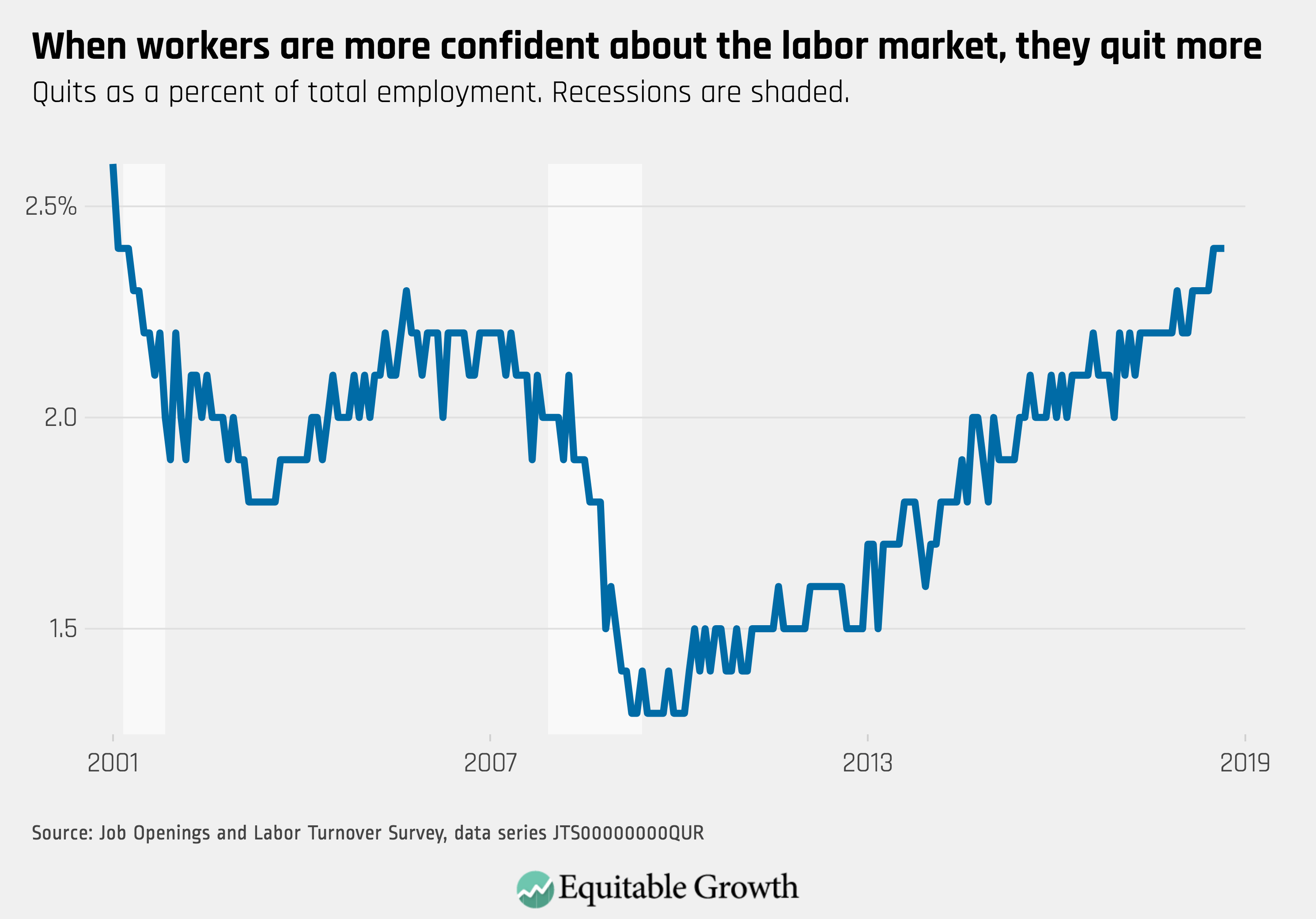

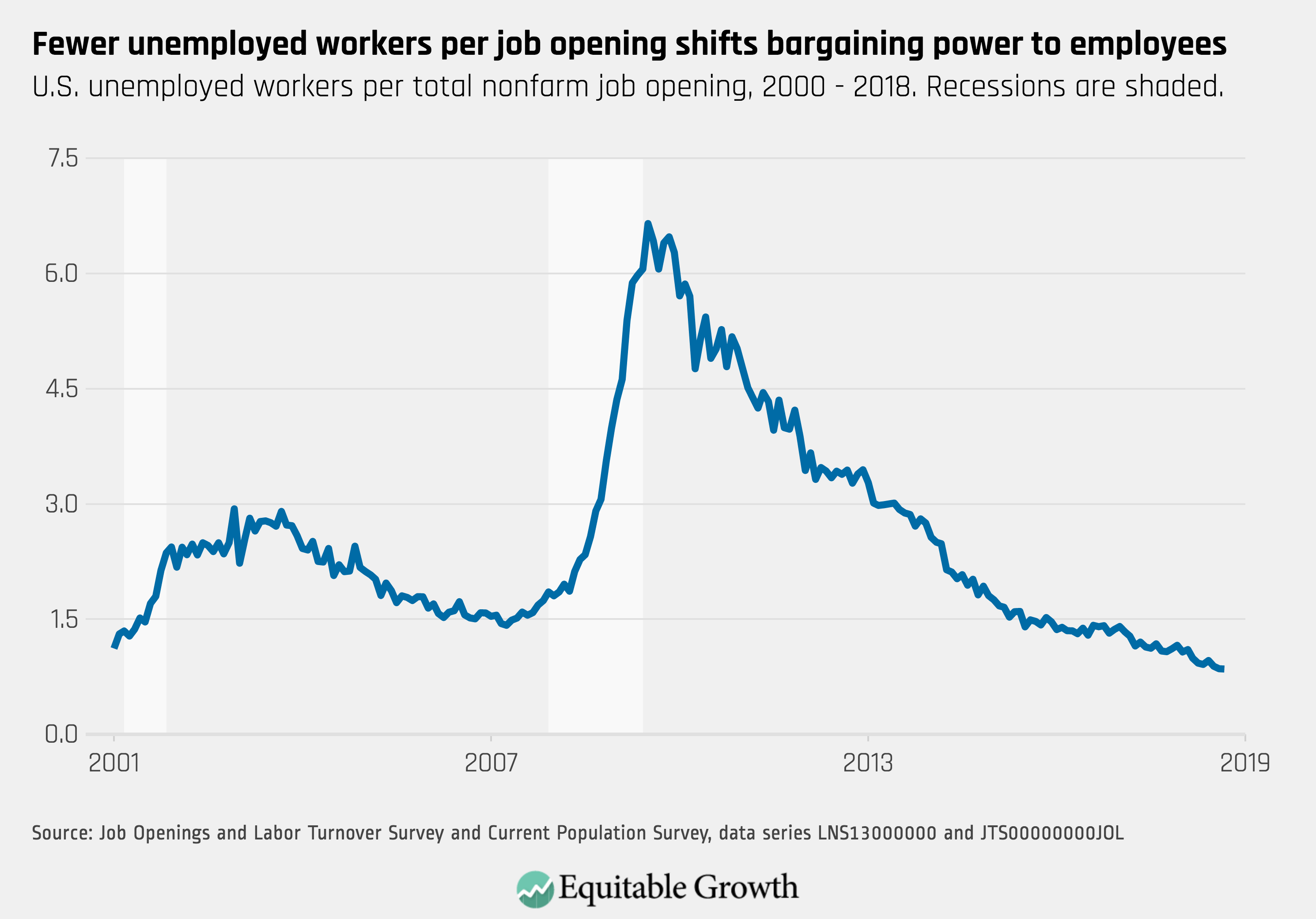

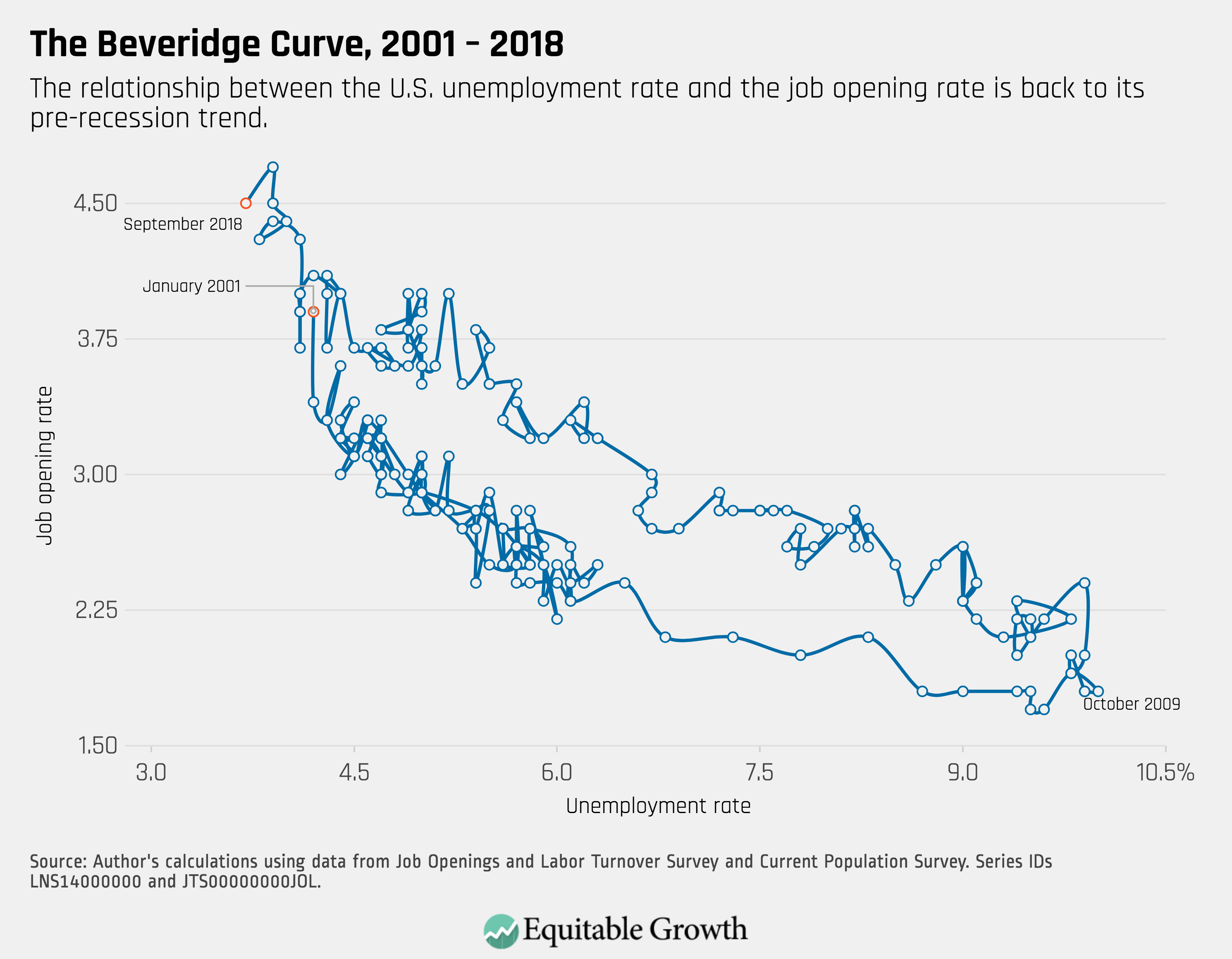

Despite its widespread impact, the search and matching model has faced criticism for failing to fully account for several empirical phenomena in contemporary labor markets, notably the cyclicality and persistence of vacancies, unemployment, and job creation, as well as the persistence of inflation in response to monetary shocks. As economist John Quiggin of the University of Queensland explains, one of the key criticisms of the search and matching theory has focused on its failure to accurately predict the effects of the internet on unemployment. Since the dominant framework models unemployment as a function of search and matching frictions, unemployment should have declined with the rise of the internet, which increased the information available to both employers and employees. Yet this empirical prediction did not materialize. Indeed, over the past two decades, despite sustained innovations involving the internet, unemployment spiked twice—in the early 2000s, after the dot-com bust and again in the Great Recession beginning in December 2007. In the latter case, the spike was particularly durable, as unemployment has only recently returned to healthy levels.

While these empirical critiques call into question the implications of the job search and matching model for key macroeconomic labor market variables, this model may nevertheless be helpful for understanding the internal dynamics of the job search process itself—and particularly the role of technological innovation in this process. Indeed, the centrality of transaction costs in terms of search and matching in the mainstream model is a logical frame in which to analyze the effects of technological innovations, which presumably have the capacity to reduce various types of frictions.

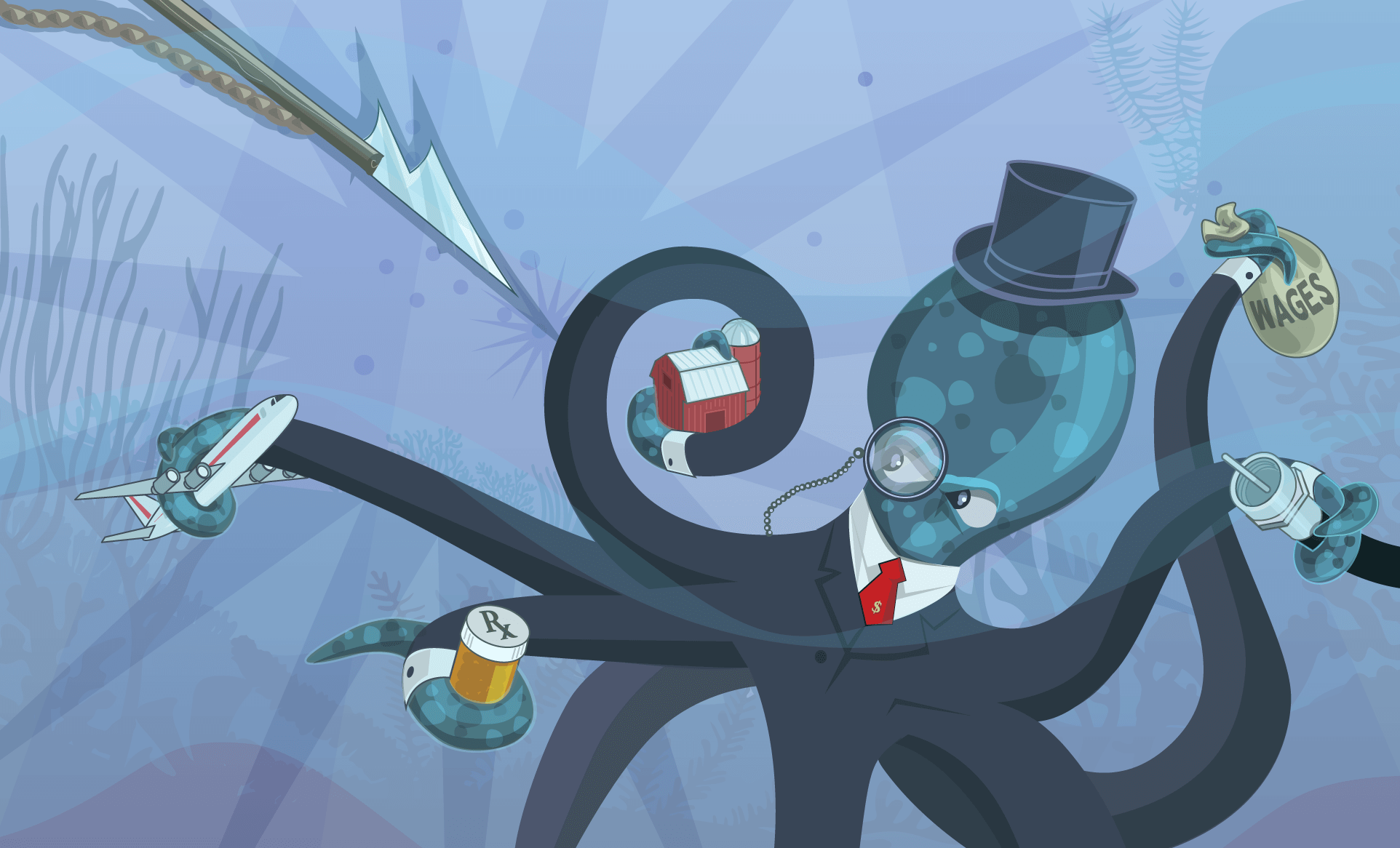

Instead of discarding this model, a future research agenda should build on it while incorporating important structural frictions in the contemporary U.S. labor market, notably monopsony (or the dominance of a small number of employers), occupational segregation (the disproportionate concentration of women and ethnic minorities in certain fields), and labor market polarization (the recent increase in low-skill, low-wage and high-skill, high-wage jobs at the expense of middle-class employment). Including both structural and informational frictions in the Mortensen-Burdett model also sheds light on points of intervention where innovators and policymakers can help facilitate a more efficient and more equitable job search and matching process. For example, in Alan Manning’s book, Monopsony in Motion, the economist describes how lack of information, among other frictions, is pronounced when there are too few employers in a single labor market, underlying the importance of public intervention to prevent labor market concentration.

At the very least, better matching technologies could help reduce informational search frictions and the related skills mismatch—with positive implications for both inequality and growth. With the goal of improving existing job boards and similar platforms as a starting point, companies—including Alphabet Inc’s Google unit and Indeed—have begun to use artificial intelligence and machine learning to narrow down the most relevant jobs for job-seekers. Indeed also uses natural language processing to help employers identify the best candidates for vacancies by analyzing language from applicants’ resumes and other submitted materials. These technologies and further innovations in this vein would enhance both the equity and efficiency of labor markets by reducing the inequality associated with skills mismatch and search frictions, driving down unemployment given shorter search times and increasing labor force participation and work hours in response to improved matching to jobs consistent with workers’ skills and interests. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that these advances could add 2 percent to global GDP in the next decade.

Innovative job-matching platforms, especially those integrated with training programs, can also strengthen workers’ human capital, as well as their bargaining power in the labor market. Companies such as CodeSignal (formerly CodeFights Inc.), for example, are creating online platforms that allow job-seekers to practice their skills and earn credentials, which they can use to be matched with employers and job opportunities. If programs such as those offered by CodeSignal are successful in helping applicants develop the skills required for particular job opportunities, then the credentials they provide could become strong signals giving credentialed job applicants increased leverage in the recruitment process. In essence, these technologies could help create digital apprenticeships of the future, which combine training programs with pathways to gainful employment.

These platforms can further increase workers’ human capital, exit options, and bargaining power in their current jobs by providing them with opportunities for professional development and notifying them of relevant job postings as they open up. In particular, with the help of artificial intelligence, these services can keep workers informed of how their salaries and benefits compare to those of new vacancies, further solidifying their bargaining position without taking time and energy from their job responsibilities. The combined effects of innovations in this vein may reduce the search frictions workers face in transitioning between jobs in search of higher pay and a better overall fit. Program evaluation and further research on how job training and greater comparative information on wages and benefits impacts both matching and bargaining power are needed to ensure that technology is addressing the needs of workers and reducing structural inequality in labor market outcomes.

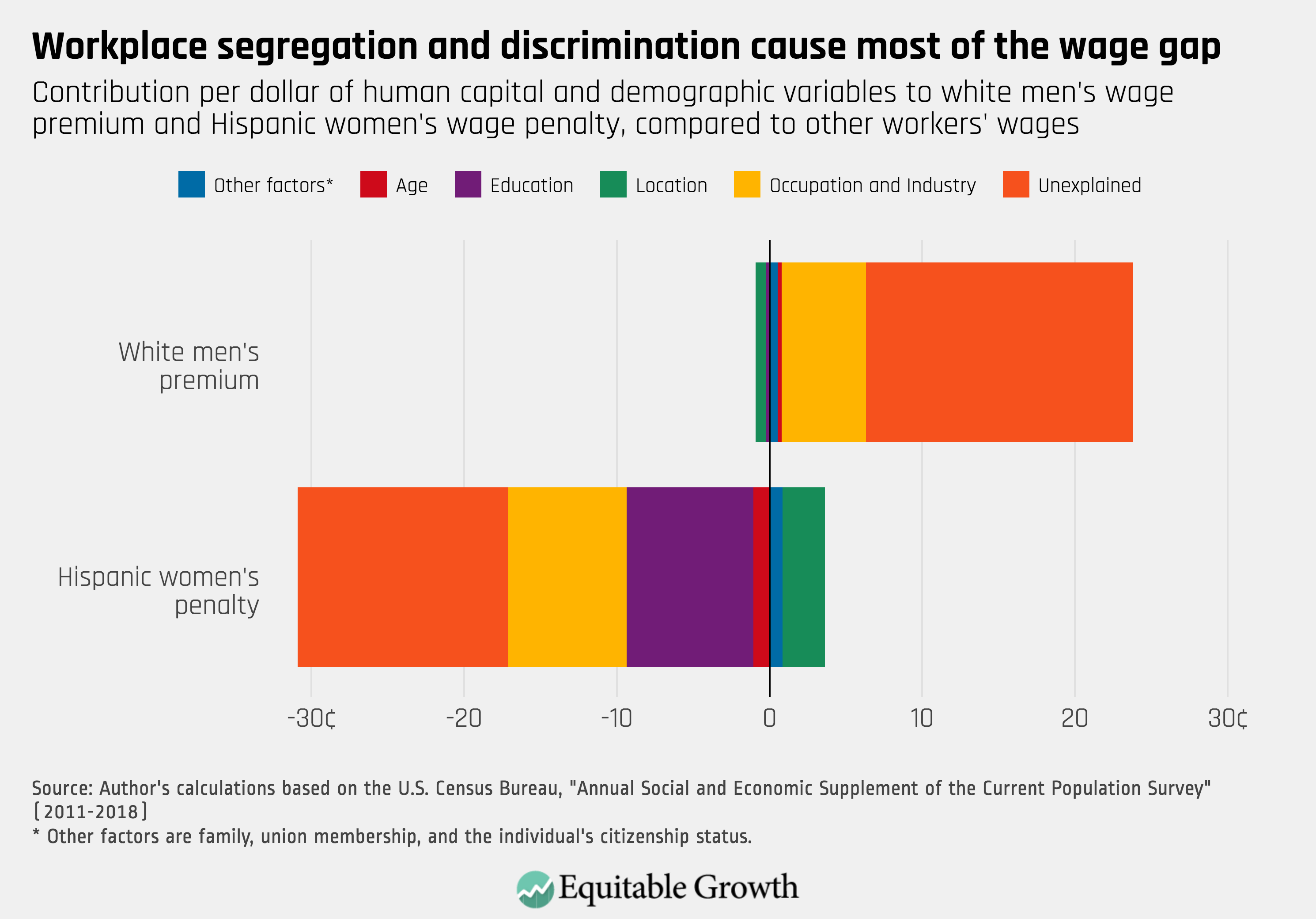

In addition to mitigating power imbalances between workers and firms, matching services powered by AI and machine learning can be crafted to reduce occupational segregation by race, gender, and socioeconomic class. This is important because segregation remains one of the most important factors leading to wage discrepancies faced by workers based on their demographic identity and not their productive capacity. From the labor demand side of the equation, job-matching services can bring more objective standards and processes to the recruitment pipeline, thereby reducing the influence of implicit biases and social networks in hiring decisions. Well-known research from Harvard University economist Claudia Goldin and Princeton University Woodrow Wilson School Dean and economist Cecilia Rouse finds that concealing demographic information of job applicants increased gender representation among orchestras, demonstrating the need for matching by observable skill rather than demographic characteristics that may reinforce discrimination.

Along with the training and credentialing efforts discussed above, other startups, among them the recruitment and talent assessment company Harver, have partnered with employers to create job-specific assessments along these lines that identify the most qualified candidates for a given position based solely on the actual skills required for the role. In turn, on the labor supply side, job-matching services can expand the horizons of job applicants from underrepresented gender, racial, and educational groups to occupations and industries they may not have traditionally considered. Specifically, these services could match workers to jobs that are higher paying but require skills these workers may have already gained or could acquire without much difficulty in a training program.

Despite these promising developments, recent research has documented that AI, machine learning, and other innovations can often be inadvertently programmed to reproduce existing biases in labor market institutions. Job-matching technologies undoubtedly have the potential capacity to reduce labor market inequalities—both between employers and firms and among various groups of workers. But in order to realize these objectives, technology developers and policymakers must recognize that labor market monopsony, occupational segregation, and job polarization create frictions in the contemporary U.S. labor market that are arguably as significant as those created by informational inefficiencies. As such, any truly efficient matching system must be intentionally calibrated with the help of rigorous social science research to reverse all three trends.

Beyond their potential role in reducing unemployment and improving workers’ human capital and bargaining power, public and private efforts to reduce search frictions and skills mismatch stand to strengthen aggregate productivity growth and thus the overall health of the economy by providing workers with more fulfilling opportunities, incentivizing employers to innovate and compete for talent, and ensuring workers have the skills necessary to help firms thrive.