A commonly cited statistic about trends in absolute mobility over the past half-century is Harvard economist Raj Chetty and his co-authors’ finding that while more than 90 percent of people born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents—that is, they experienced upward mobility—the same was true of only about half of people born in 1980. This striking finding is echoed by a new discussion series paper by researchers at the Federal Reserve Board looking at how measures of millennials’ economic conditions compare to those of prior generations at similar ages.

Using data from the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics and the Current Population Survey’s Household Surveys, as well as the Pew Research Center’s definitions of millennials and other generations, the paper compares the income, assets, and debt of millennials (those born between 1981 and 1997) to Generation Xers (those born between 1965 and 1980) and baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) at similar ages. It finds that “millennials tend to have lower income than members of earlier generations at comparable ages,” as well as fewer assets.

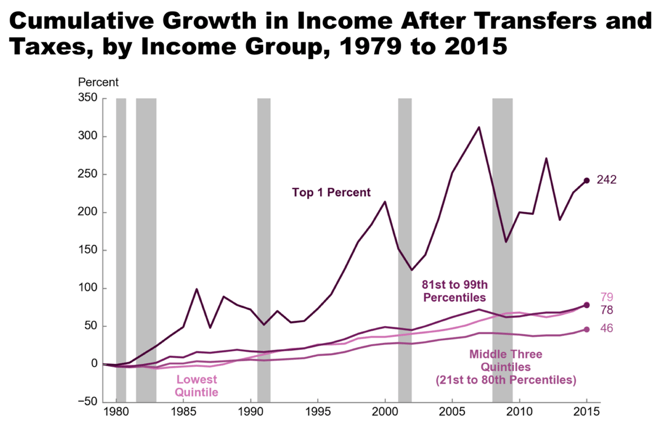

Specifically, average real (inflation-adjusted) labor earnings for men working full time were between 18 percent and 27 percent higher for Gen Xers and baby boomers, respectively, than millennials after controlling for demographic factors such as race and work status. In examining assets, the paper found that while the average value of assets held by millennials was more or less equivalent to that held by Gen Xers at a similar age, the median value of assets held by millennials ($55,000) was significantly lower than that of both Gen Xers and baby boomers at similar ages ($104,700 and $63,300, respectively). The fact that the average has held steady while the median has fallen suggests that the brunt of this downward mobility in assets has fallen more on those lower down on the distribution.

In examining debt, both the average and median debt held by millennials wasn’t dramatically different than that compared to Generation Xers overall—but not so the composition of that debt. Millennials are significantly less likely to have mortgage debt that Gen Xers at similar ages and significantly more likely to have student loan debt. “In 2004, 28 percent of Generation X members had a mortgage, well above the 19 percent share of millennials that had one in 2017,” according to the Fed report. Similarly, “While only 20 percent of Generation X members had a student loan balance in 2004, more than 33 percent of millennials had one in 2017,” says the report.

The increased prevalence of student loan balances on their own wouldn’t necessarily be concerning for millennials if the paper hadn’t also found the decline in income, which means this generation has less money to actually pay off that debt. Furthermore, because mortgage debt is less prevalent among millennials than among the immediately preceding generation, there is evidence suggesting that student loan debt is part of the reason that millennials are delaying homeownership—an asset that represents the bulk of wealth for most Americans.

What are the possible explanations for why millennials have lower incomes and fewer assets than did prior generations at similar ages? The authors conclude: “These balance sheet comparisons likely reflect, in part, the unfavorable labor and credit markets conditions that prevailed during the 2007–09 recession, some of which had prolonged effects.”

The Fed paper’s emphasis on the importance of the labor market conditions into which millennials graduated echoes the arguments made in my and my co-author Elisabeth Jacobs’ recent report, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?” In the report, we lay out a framework for understanding the channels via which upward mobility can either be facilitated or impeded, arguing that while a great deal of attention is paid to factors that develop human capital such as education, more research is needed to understand how things such as prevailing labor market conditions can impede the deployment of that human capital.

Oftentimes, when seeking to understand or explain economic outcomes, researchers and policymakers place a great deal of emphasis on the importance of the development of human capital. Two examples of this focus are the emphasis on education and training to ensure that workers have the skills required in an increasingly global and technical marketplace. Certainly, education and training are crucial components of human capital and are key to ensuring workers are able to reach their full potential, but an emphasis on improving education alone as the policy solution to ensuring economic opportunity is insufficient. As the Fed paper discusses, each generation has been more educated than the one before it, and yet the most educated generation so far has lower incomes than prior generations—and more student loan debt to boot—at similar stages in their lives.

That’s why Jacobs and I argue that more attention is needed to how factors related to the deployment of human capital can help us understand how upward mobility and economic well-being are facilitated. As the Fed paper’s findings highlight, the labor market in which a generation first finds itself seeking employment can have profound implications for their economic conditions. There is extensive economic research finding that entering the labor market during recessions has deep and persistent effects on the earnings of those workers across their lifetimes.

The importance of labor markets rather than education for explaining economic outcomes is highlighted in a recent Equitable Growth working paper by University of California, Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein, “Inequality of educational opportunity? Schools as mediators of the intergenerational transmission of income.” In it, Rothstein studies the intergenerational mobility differences for lower-income children growing up in areas where the gap in test scores is small between lower- and higher-income families. If education is a key driving force for intergenerational mobility, then one would expect to see the children from low-income families in communities with low gaps in test scores grow up to be more upwardly mobile, compared to those from areas with large test-score gaps between lower- and higher-income children. Yet his results find that children’s mobility outcomes aren’t dramatically different between low test-score gap areas and high test-score gap areas.

As Rothstein explains in a column for Equitable Growth about his working paper, these results suggest that, “There is little evidence that differences in the quality of primary, secondary, or postsecondary schools, or in the distribution of access to good schools, are a key mechanism driving variation in intergenerational mobility. The evidence instead points toward other factors influencing income inequality. In particular, labor markets seem to be quite important.”

Acquisition of human capital is, of course, a crucial factor to ensure people are as best prepared as possible to make the most of their potential. But the development of human capital is insufficient on its own to ensure that people experience upward mobility and economic well-being. Factors beyond their control—particularly the condition of the labor markets they find themselves in—play a significant role in their ability to fully deploy that potential. More attention needs to be paid to what the factors might be that impact that deployment of potential and what policies could ensure that upward mobility isn’t stymied by economic conditions outside of any individual’s control.