The Federal Reserve Board last month took extraordinary actions to deal with the financial shocks delivered by the coronavirus pandemic. And Fed action, in a number of ways, will determine how well the recently enacted $2.2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act deals with the looming coronavirus recession. Amid all of these fast-moving events, economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman at the University of California, Berkeley invited me to join an online convening of more than 100 other economists and experts to discuss the role of U.S. financial stabilization policies in the current economic and financial situation.

Following is a summary of my comments at the convening on March 24 and a few thoughts following the enactment of the CARES Act.

There are three important questions that need to be answered about U.S. financial stabilization policies in today’s financial and economic situation. Where do financial stabilization policies fit into the overall set of policy responses? What has been done so far? And what more needs to be done? And, to be clear, financial stabilization policies include monetary policy, emergency liquidity policies, and financial stability, or macro-prudential, policies.

On the first question, financial stabilization policies cannot, on their own, solve the current crisis. They stand behind the public health responses, which are paramount. They also stand behind fiscal policies that can offer direct relief to households and businesses harmed by the spread of the coronavirus.

But financial stabilization policies are critically important. They address the economic and financial fallout by reducing the cost of borrowing and ensuring the flow of credit that households and businesses need. While less direct, financial stabilization policies can’t wait until the others are in place. Financial markets won’t wait. For them to function, they need to be able to measure risk and return. But this has been extremely difficult amid the huge range of uncertainty brought on by the spread of the coronavirus, leading to high volatility and market dysfunction. Financial policies can help to stabilize the situation.

Combined, the policies will place some boundaries around the range of uncertainty of how deep the cuts to U.S. economic activity will be. That will provide information about a lower bound for the extent of losses that investors and financial institutions are likely to take. Financial stabilization policies can provide liquidity to prevent unnecessary insolvencies. But a longer-term solution to the economic costs of the coronavirus has to involve fiscal transfers, with a solution for how to share across society the costs of this pandemic.

Turning to the second question about what has been done, monetary policy was the first step taken. The Fed cut interest rates twice, and now rates are at the effective zero lower bound. The Fed still could do more with forward guidance or quantitative easing. But I think the primary issue is not about whether interest rates are low enough to encourage more borrowing. Instead, it’s about ensuring that credit continues to flow to households and businesses. The actions that the Fed has taken so far to increase liquidity have helped on that score. Liquidity, though, is not capital. It’s a bridge to a longer-term solution.

On emergency liquidity provisions, I’ll mention a few things that policymakers have done in broad terms. I could discuss very detailed, acronym-laden programs, but I think it’s probably more useful to think in broader terms.

First, the Fed has quickly purchased a large amount of Treasury and other federal government securities. Many people call these asset purchases quantitative easing, but they actually are intended to address market dysfunction. There were some odd signs in U.S. Treasury securities markets a few weeks ago, likely owing to unwinds of leveraged positions and increasing operational risks with a high volume being transacted away from typical business settings. The Treasury securities market is especially important because Treasury securities are used to price many other assets.

Most of the other facilities opened by the Fed are targeted to getting credit to businesses to keep their cash positions intact, to maintain investments, and to keep employees. For example, there’s a facility to which investment-grade corporations can issue commercial paper, one in which investment-grade corporations can issue medium-term bonds and loans, and one to support issuance of asset-backed securities.

These facilities are funded with capital from the U.S. Treasury Department through the Exchange Stabilization Fund and loans from the Federal Reserve. Capital provided by the Treasury is a critical element. The Federal Reserve can lend only if “secured to its satisfaction.” In the 2008 financial crisis, capital was provided by the Troubled Asset Relief Program to facilities where the Federal Reserve could not otherwise be secured to its satisfaction. Note that with the passage of the CARES Act at the end of March, the U.S. Treasury Department has an additional $454 billion in the Exchange Stabilization Fund, which it can provide as capital for facilities that the Fed can then lend against and provide needed financing to businesses.

Many facilities rolled out by the Fed in March had been used in 2008. In an effort to get them out as quickly as possible, some were released with the exact same terms and adjusted later. But some actions are new, such as facilities for investment-grade corporate bonds. Another new set of actions are macro-prudential policies, most of which were developed after the crisis.

The most visible new macro-prudential policy is to encourage banks to draw down the capital and liquidity buffers that they have built up since the end of the previous crisis. Current capital ratios are much higher than they were going into the past crisis. Capital buffers can be used to absorb losses and support lending. There is an open question, however, about how much capital buffers should be drawn down, given the uncertainty about how deep this recession could be.

Federal banking regulators also recently issued guidance to financial institutions to defer payments on loans to borrowers harmed by the coronavirus. That action will give households and businesses up to six months where they may have to pay only interest and can defer the principal. Debt is not extinguished, but borrowers are given more time to make payments. Subsequent guidance clarified that loan modifications for borrowers harmed by the virus would not automatically result in an immediate capital charge.

In addition, banks voluntarily agreed to suspend share repurchases for at least through the second quarter. That may seem like a small action, but the eight largest banks last year conducted $100 billion in share repurchases. To put that in context, the new pool of capital for business lending provided in the CARES Act is $454 billion.

Turning to my third question: What else needs to be done? I think one of the more important areas is to offer more help to small businesses. There isn’t yet a broad solution for small- and mid-sized businesses that have had to shut down because of the pandemic. THE CARES Act includes a major program with $349 billion in capital for loans to small businesses through a U.S. Small Business Administration framework, with possible loan forgiveness if businesses retain their employees. But the SBA framework is limited and will not reach mid-size businesses.

A facility such as the new Main Street Business lending program in the CARES Act could offer loans to help businesses bridge the immediate reduction in income to an economic recovery down the road. This solution requires a determination of how much of the costs the mid-sized businesses and their lenders will bear themselves, and how much the broad taxpayer base will share through capital provided by the Treasury.

Another area that needs attention is the possible consequences when households and businesses defer their mortgage payments. Residential mortgage modifications caused problems in the 2008 financial crisis because missed payments would mean investors in the mortgage-backed securities into which these individual loans were bundled did not receive their interest. This led to large declines in asset prices and follow-on fire sales. In the current situation, where payment shortfalls are temporary, a liquidity solution for homeowners and mortgage servicers can help to prevent it from becoming a solvency problem.

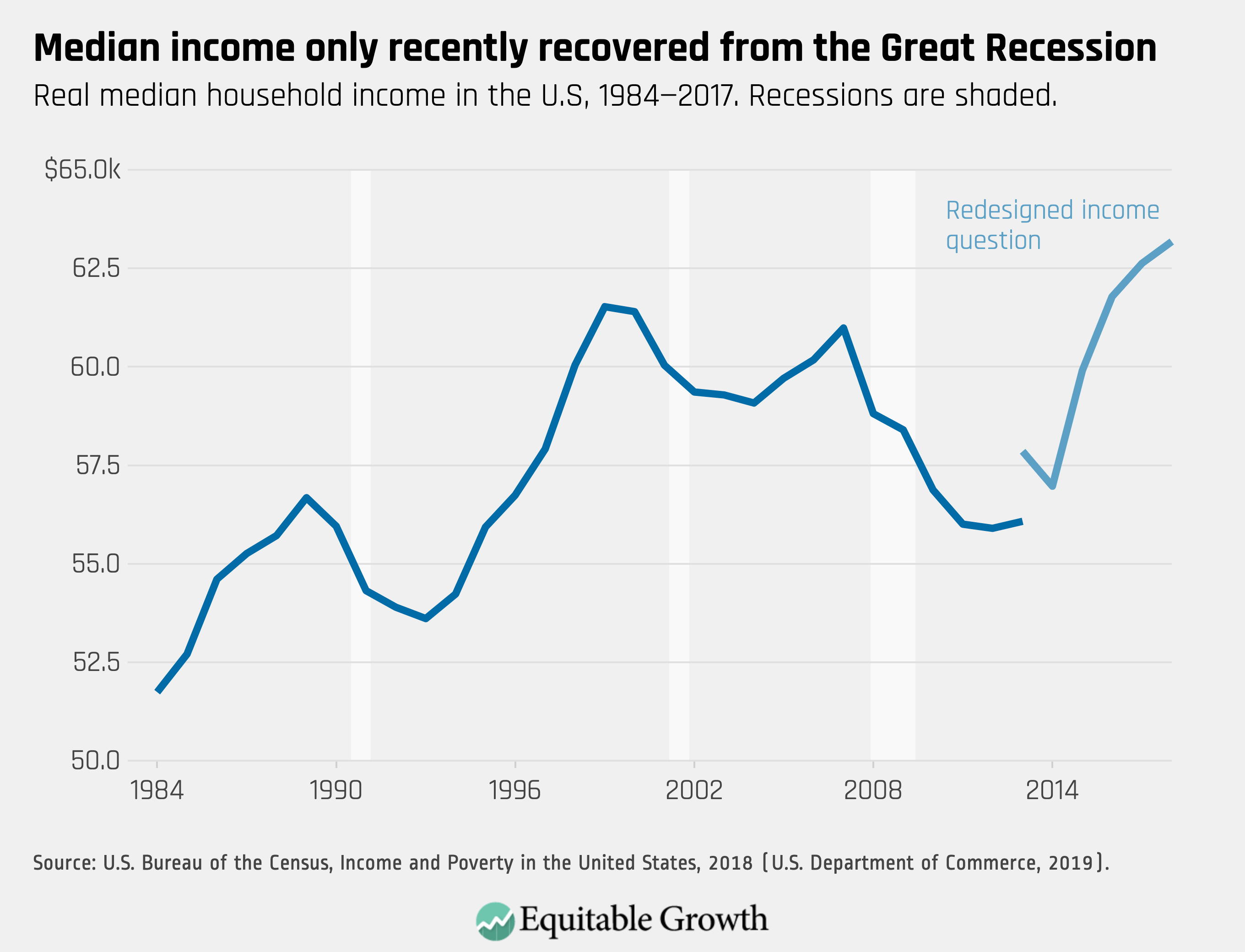

The last area for financial stabilization that I would like to mention are policies to ensure the largest banks have sufficient capital to weather a severe protracted recession. That will ensure the current recession doesn’t become deeper and longer than it needs to be. Banks have entered this recession with capital and liquidity buffers in place. And they are suspending share repurchases temporarily. But the plunge in activity in the second quarter of 2020 will be much deeper than in any quarter of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, and more actions may be needed. It is critical to a quick and strong recovery that the solvency of financial institutions is not questioned, and they can continue to function as intermediaries. This is a critical issue to get right.

—J. Nellie Liang is an economist and a senior fellow at The Brookings Institution. She previously worked at the Federal Reserve Board as a research economist and was the director of the Division of Financial Stability.