Many U.S. labor market indicators suggest that the United States is on its way toward a strong recovery. Over the past few months, hopeful signs are starting to emerge that workers in general, and low-wage workers in particular, are now in a better position to bargain for higher pay and better working conditions. But to ensure that a strong labor market recovery translates into sustained wage gains and broadly shared economic growth, workers need not only access to jobs but also access to good jobs.

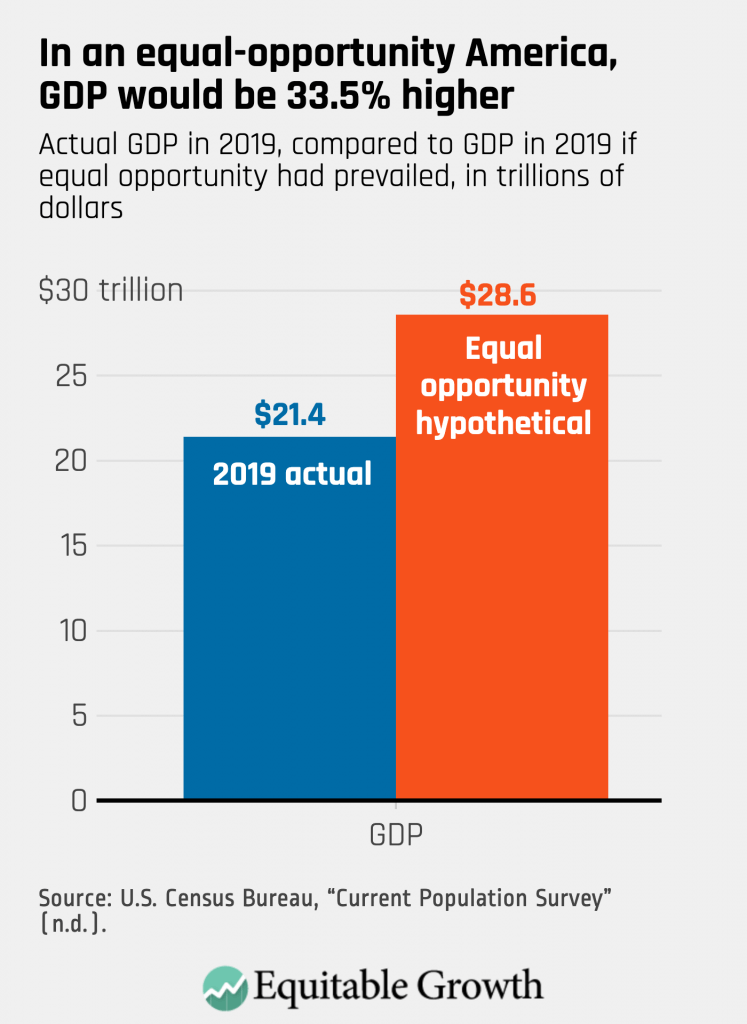

U.S. workers also need government investments and support for social infrastructure to ensure strong, healthy, and broadly shared economic growth. These types of policies fall into three major categories. The first is labor market protections, such as raising the federal minimum wage. The second is enhancing our system of income supports, such as reforming Unemployment Insurance so that enhanced benefits trigger on and off automatically, enacting a federal paid leave program, and permanently expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. And the third is strengthening our care infrastructure by providing supports to workers with caregiving responsibilities, including child care and community-based services and supports for older adults and people with disabilities. All of these social infrastructure investments ultimately boost U.S. economic productivity.

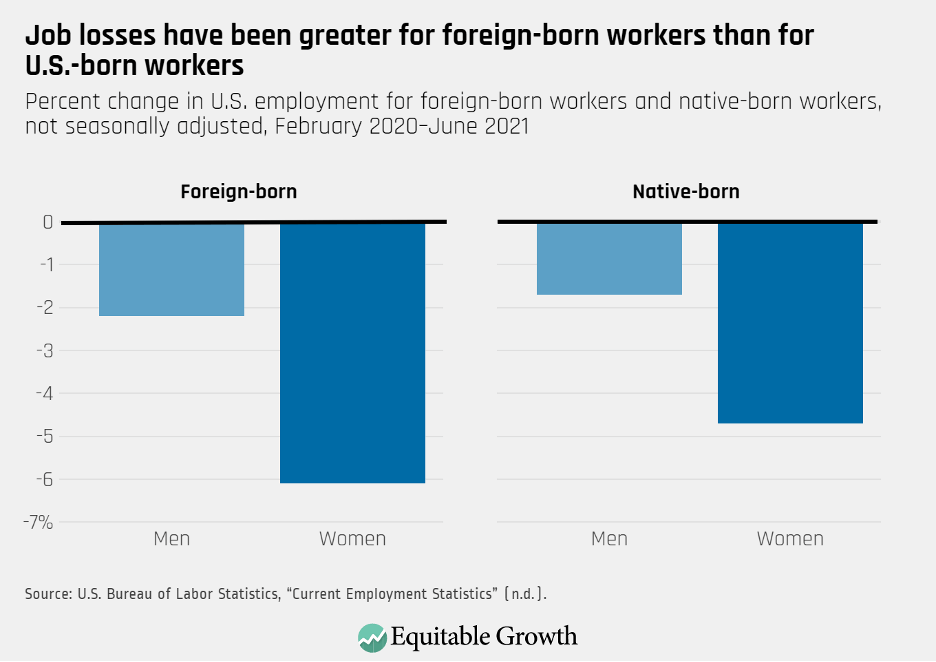

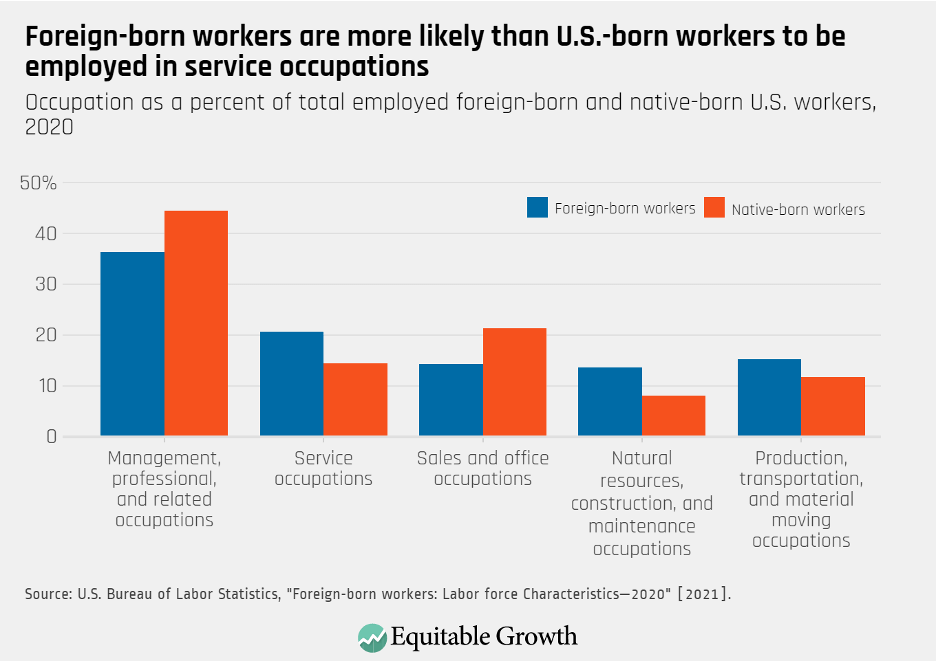

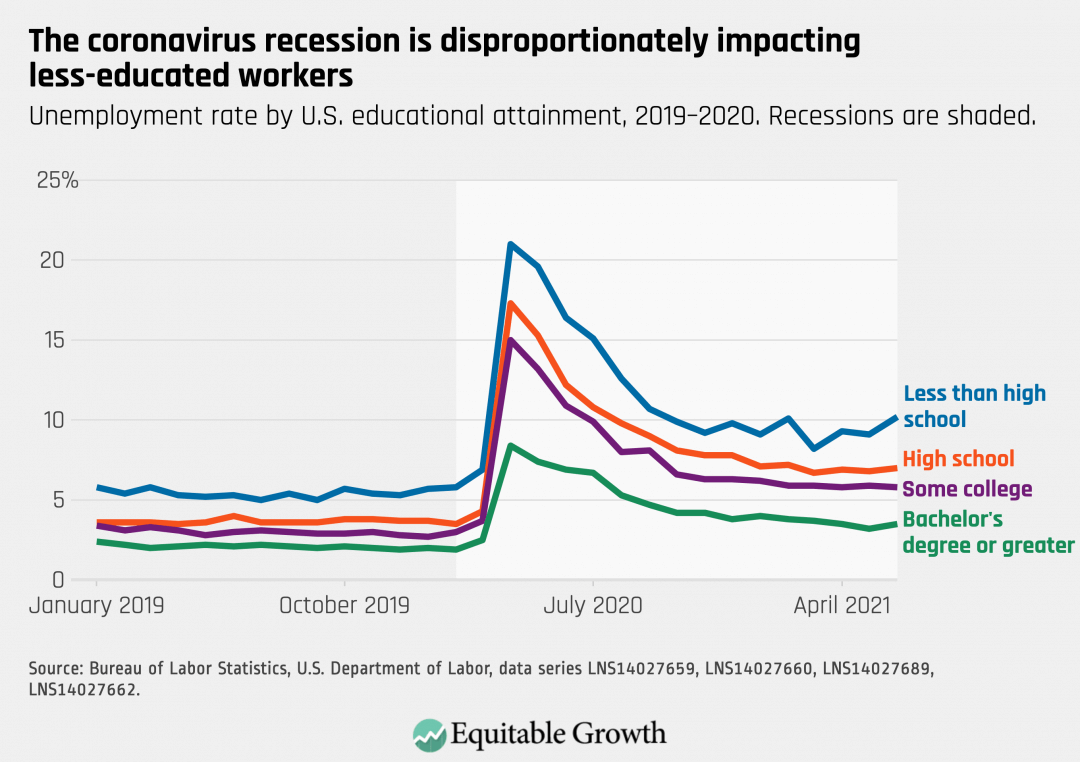

These investments in basic social infrastructure are a long time coming. The coronavirus recession hit already vulnerable workers and families first and hardest, exposing longstanding disparities that were present in the U.S. economy well before the onset of the crisis. Now, amid overblown fears about inflation and so-called labor shortages, it’s time for policymakers to invest in social infrastructure to ensure a more equitable and resilient post-pandemic economy. After all, a truly competitive U.S. labor market is not a policy failure, but rather a sign of a healthy, well-functioning economy.

Many labor market indicators suggest the U.S. economy is on track to a strong recovery

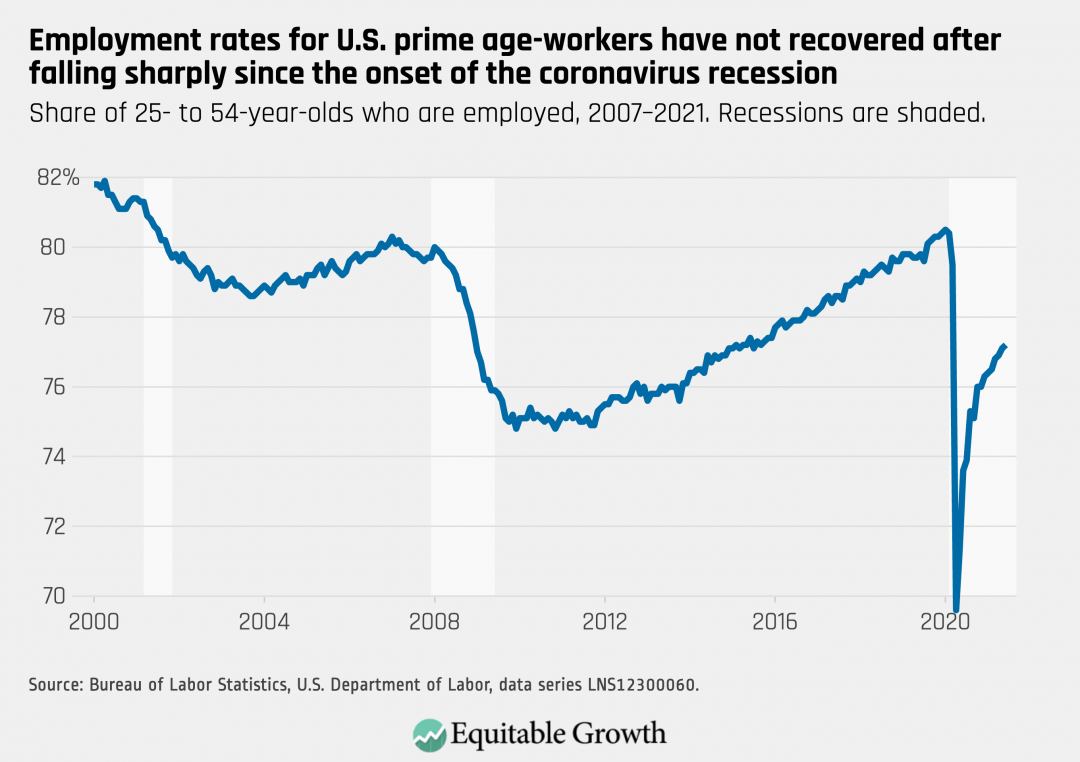

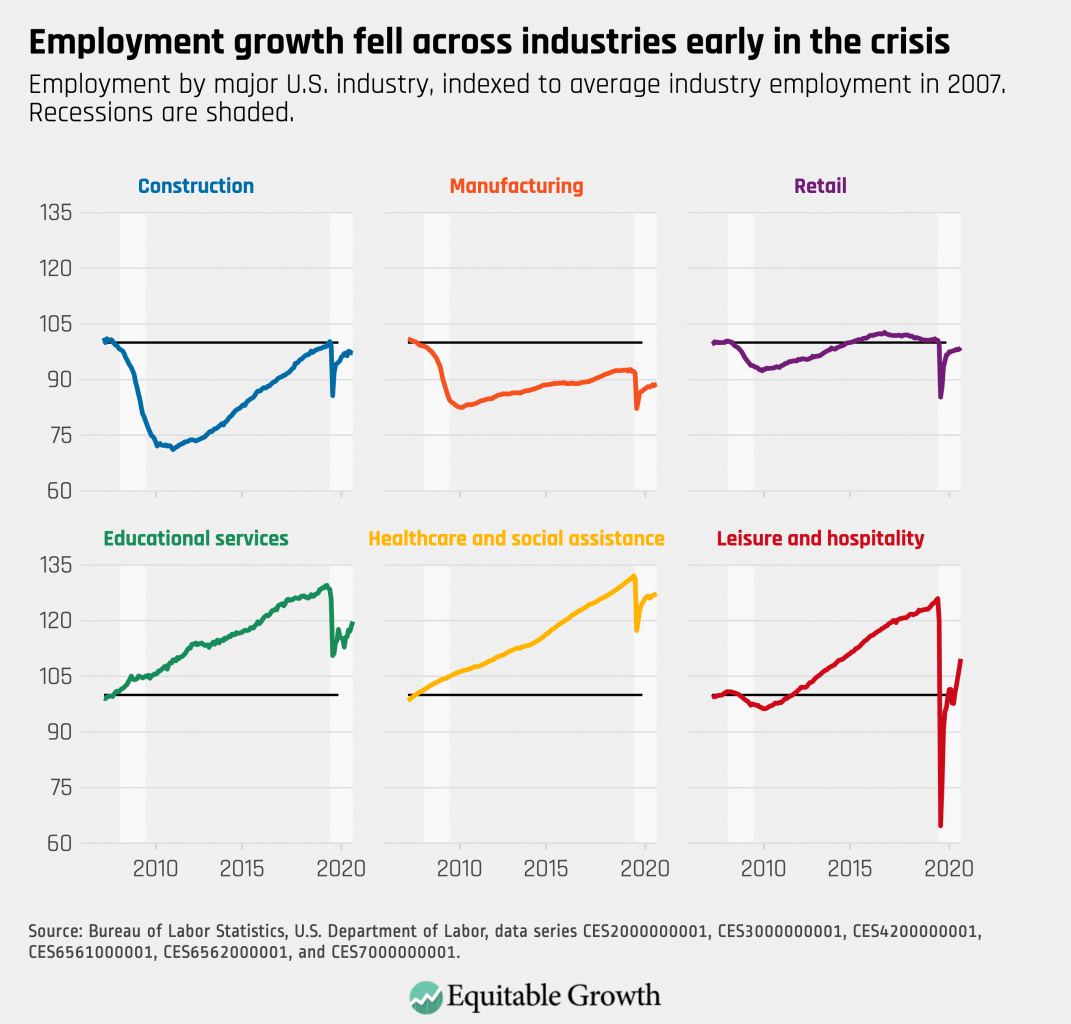

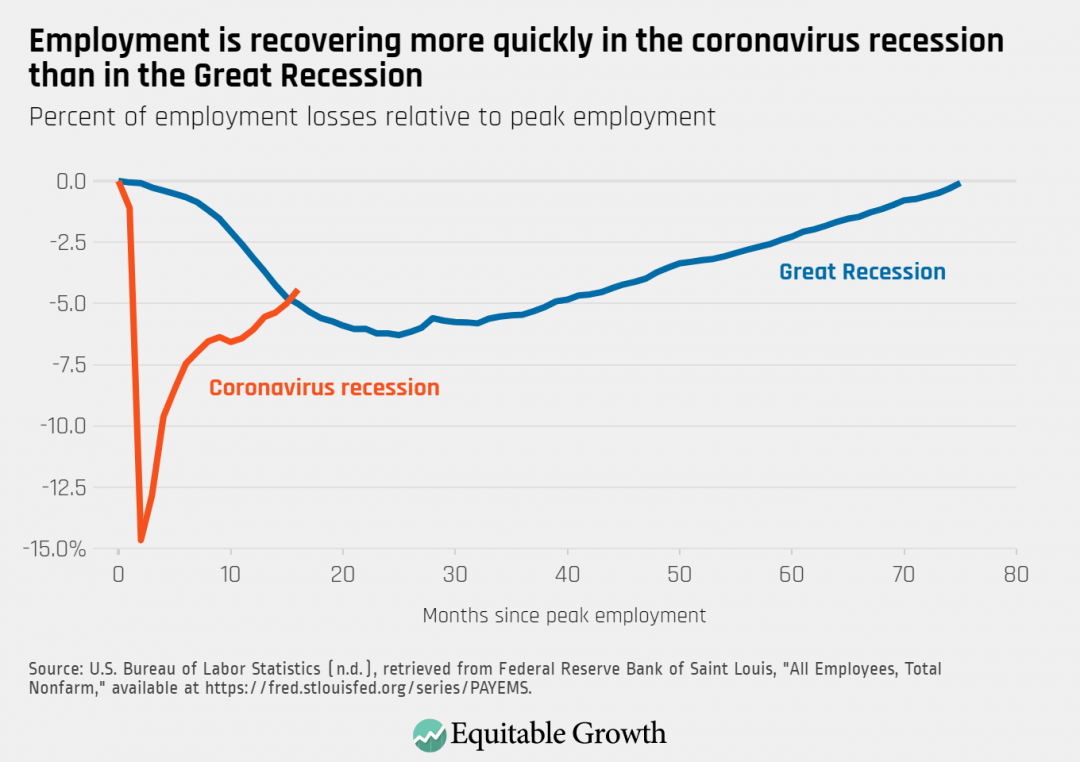

By many metrics, the U.S. labor market seems to be experiencing an exceptionally strong bounce back. As of June, the U.S. economy had recovered about 70 percent of the more than 22 million jobs lost between February and April 2020 as the coronavirus spread swiftly across the nation. This rapid recovery is in contrast to the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, when it took until early 2013 for the economy to recover the same share of lost employment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

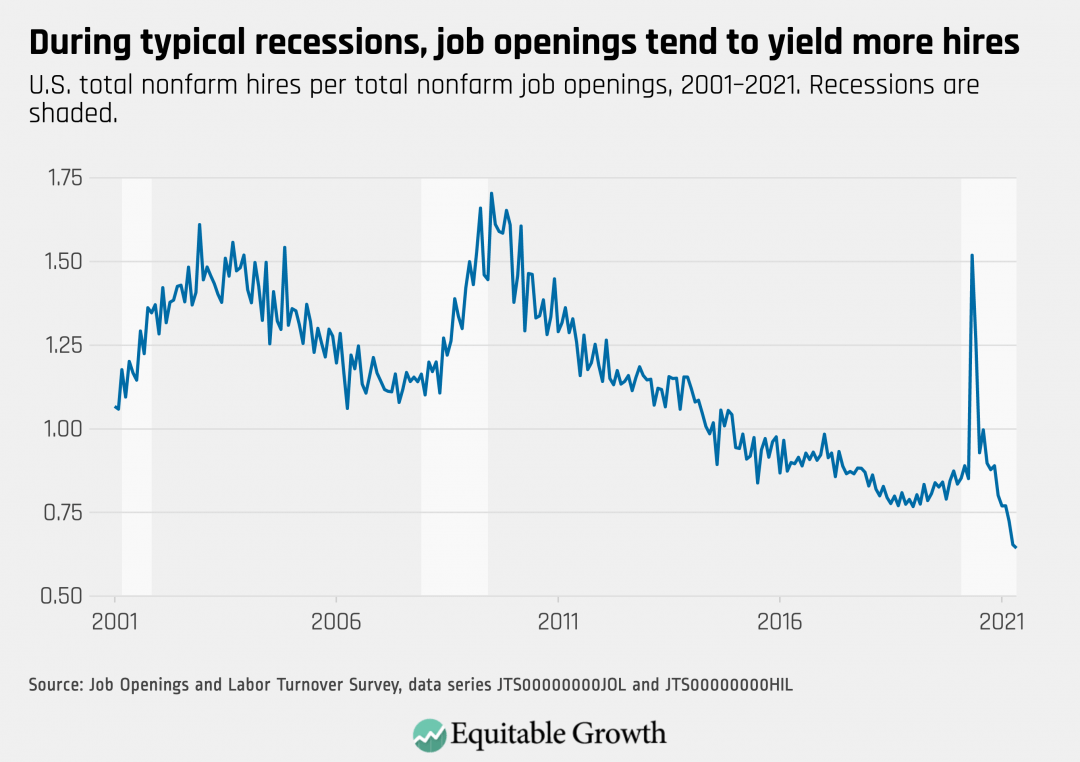

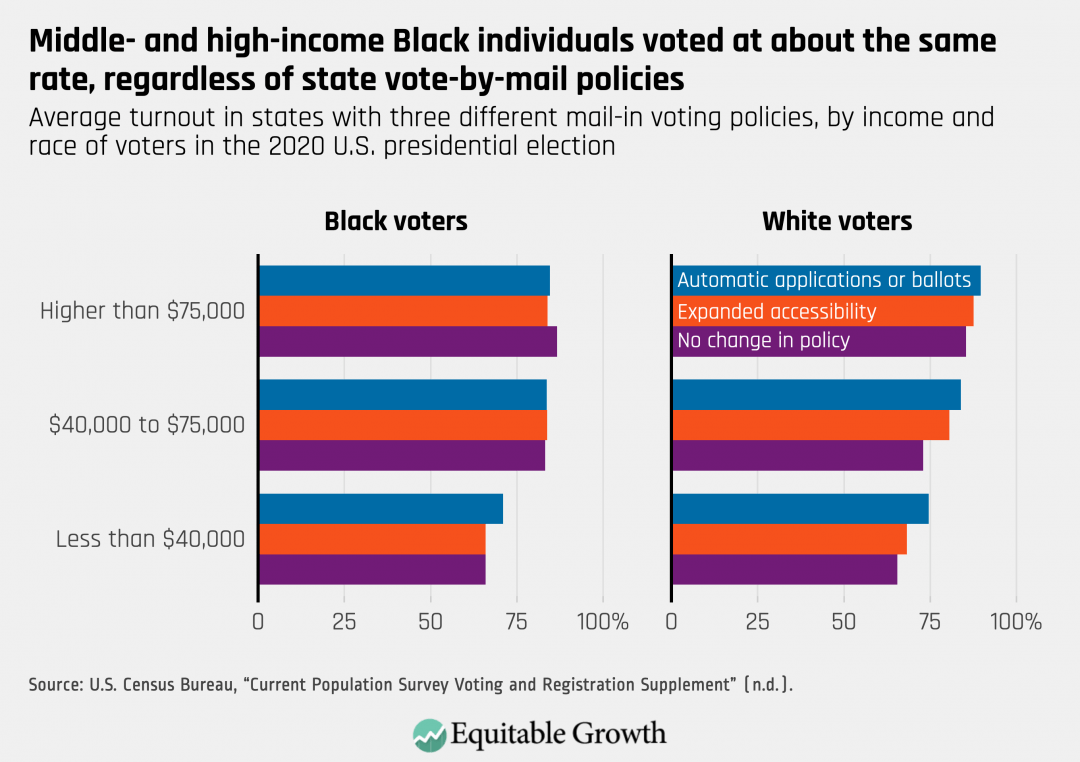

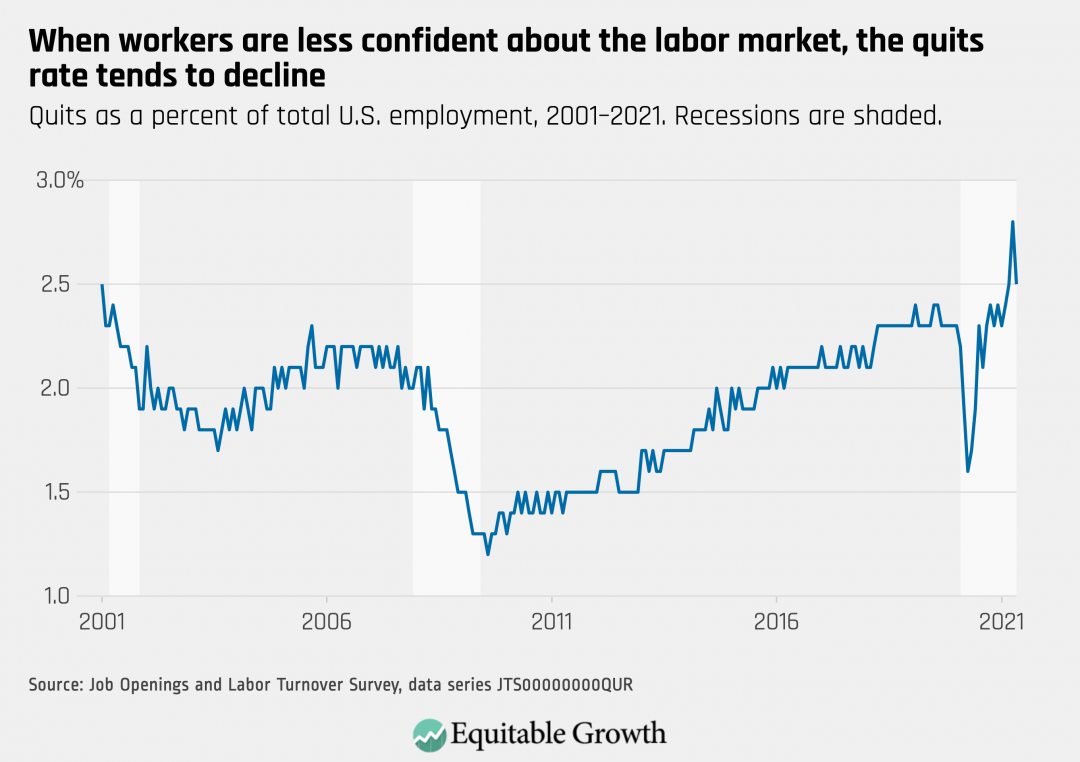

As states, cities, and localities continue to lift coronavirus-related restrictions and increase access to vaccines, sectors such as education, healthcare, and leisure and hospitality—the industries that grappled with the greatest employment losses during the first months of the pandemic—are seeing customers come back and are recovering jobs. In addition, in April of this year, both the number of workers quitting their jobs and job openings hit their highest rates since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics began publishing these measures two decades ago. In May, the most recent month for which data are available, the job openings rate remained unchanged. While the quits rate declined, it remains well above its pre-pandemic level. These two dynamics suggest that many workers are feeling confident about their job prospects as demand for labor surges.

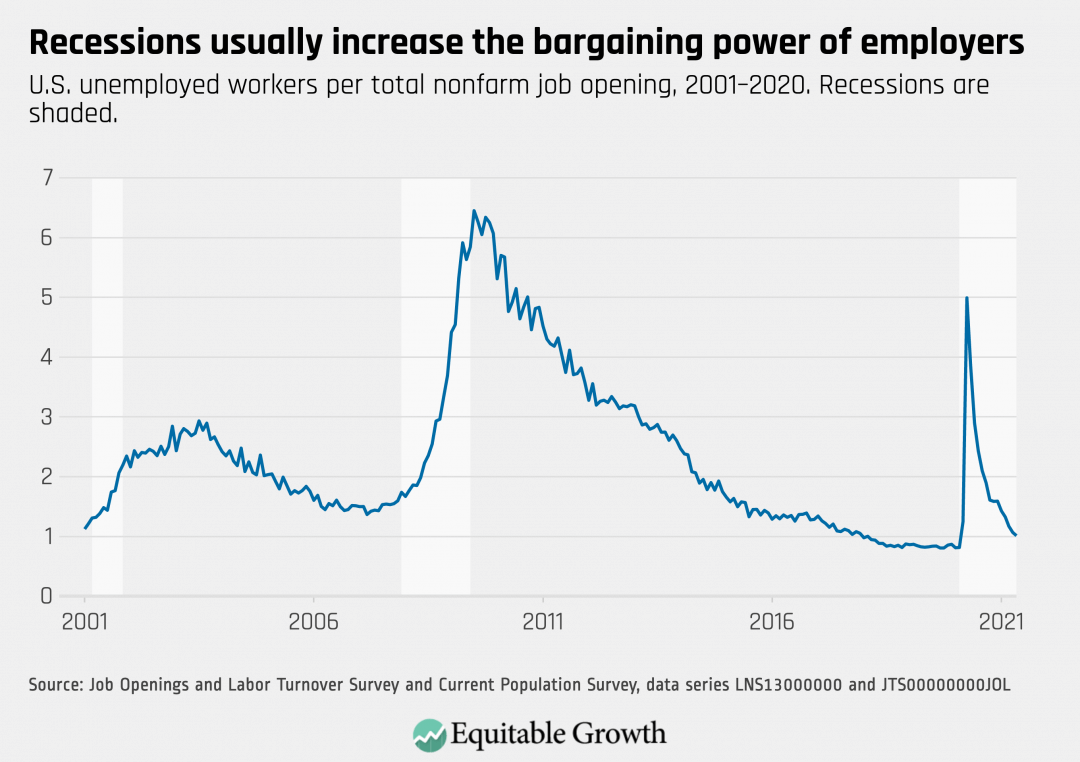

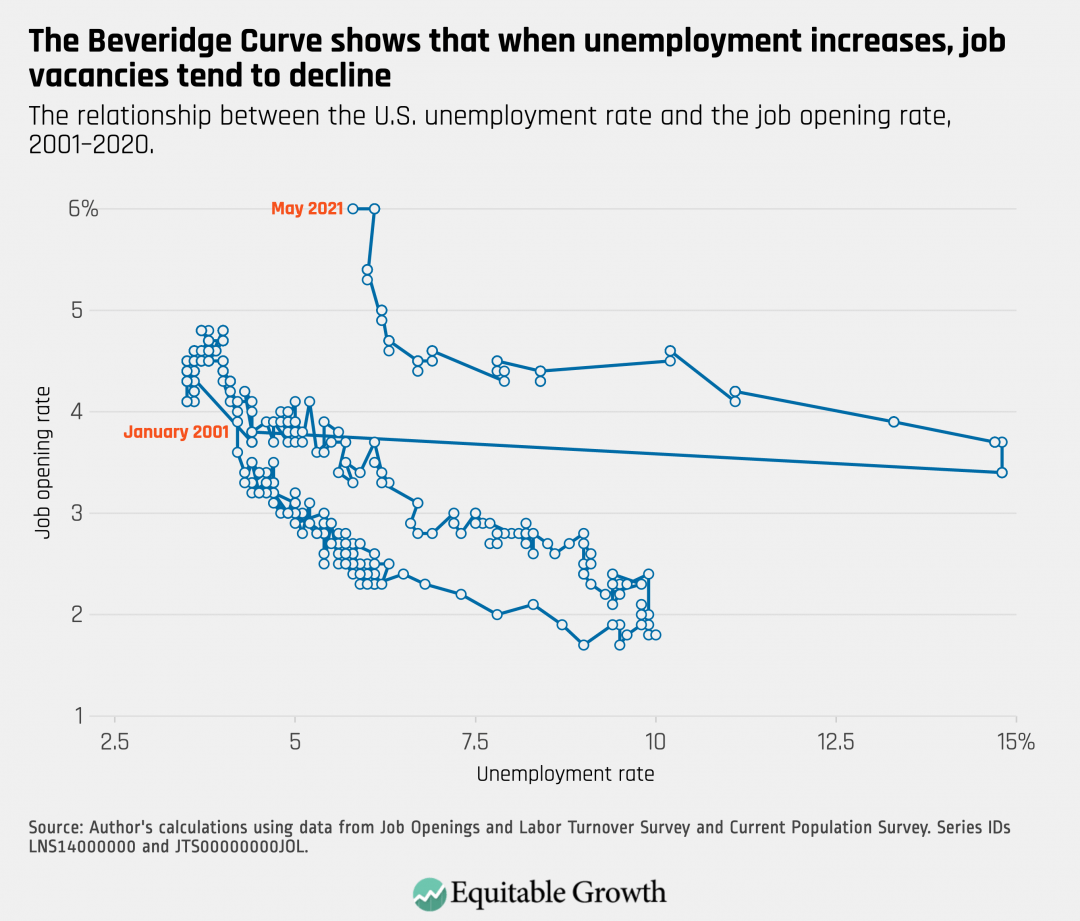

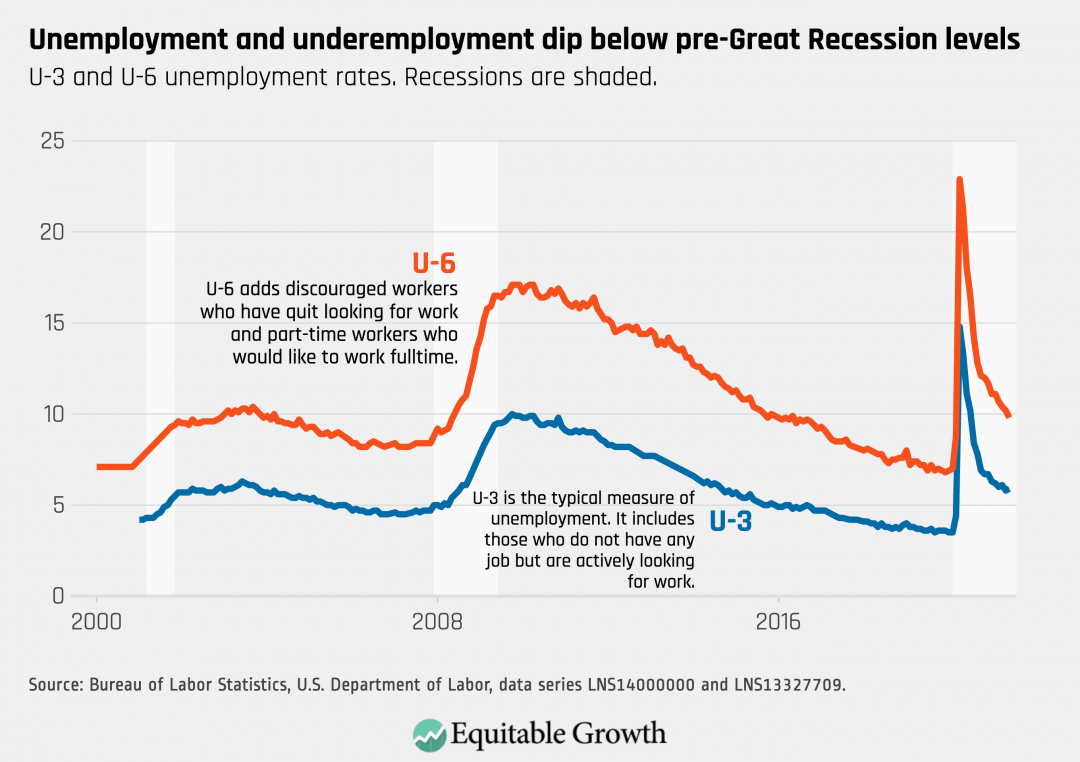

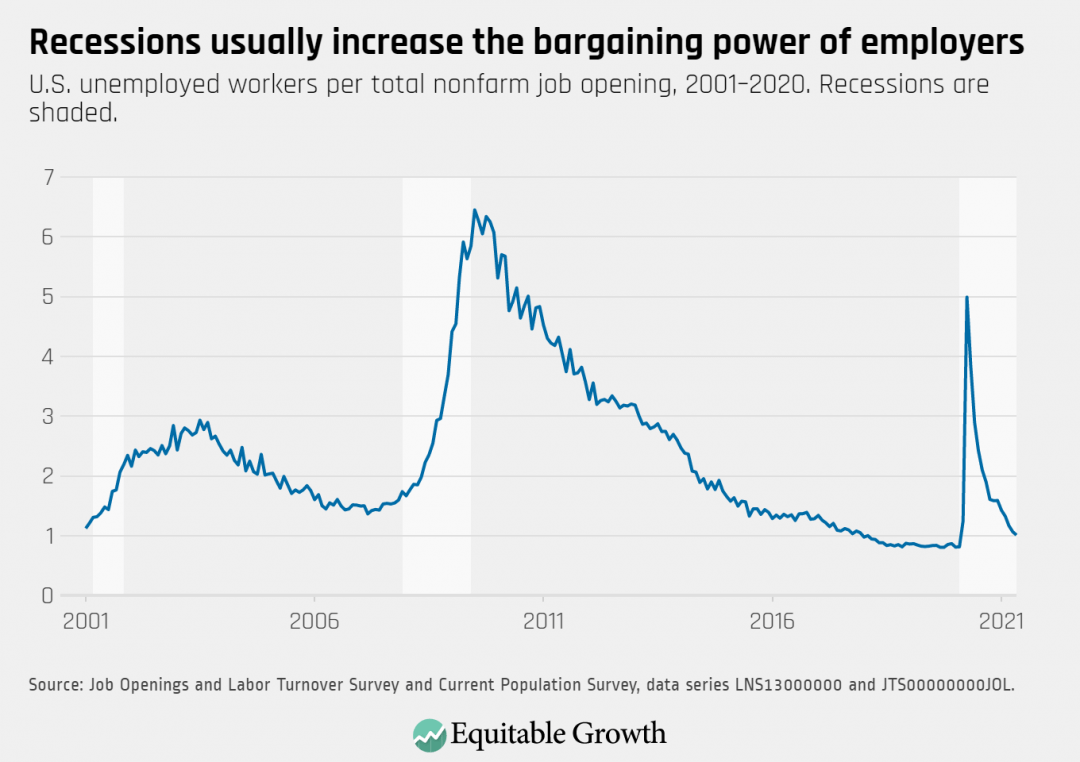

Indeed, there is now about one unemployed worker for every job opening, slightly above the 0.8 jobless workers per job opening of the tight labor market of late 2019. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Wage growth might also be picking up, although the data are ambiguous at this stage. Adjusting for composition effects—shifts in the mix of workers employed—data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show that wages and salaries rose 1 percent over the 3-month period ending in March 2021, compared to 0.8 percent in the previous quarter. And over the past few months, wage gains have been especially strong for nonsupervisory workers in lower-paying sectors such as leisure and hospitality, transportation and warehousing, and retail.

Yet the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s wage growth tracker, which follows the same workers year over year, slowed down from 3.4 percent in March to 3 percent in May. More time and data are needed to observe the wage effects of the recovery at this point.

Then, there are some economic indicators that paint a less optimistic picture. First, there could be more slack in the labor market than the headline unemployment rate suggests, so there is room for growth in labor demand, employment, and wages. The labor force participation rate, which captures the share of U.S. adults either employed or actively looking for work, has remained at roughly the same level since it fell to its lowest point in a generation last summer. And the caregiving crisis in this country is not over: The U.S. Census Household Pulse survey documents that the number of adults pointing to caregiving as the main reason for not engaging in paid work climbed from 9 million in late March to more than 11.5 million in mid-June.

This means the record-breaking quits rate and unusually low transitions from unemployment to employment are capturing not only workers’ confidence in the labor market but also shifting work and caregiving responsibilities as the pandemic subsides, workers’ reassessment of their career path, and concerns about safety amid the ongoing pandemic and disparate vaccination rates across the country.

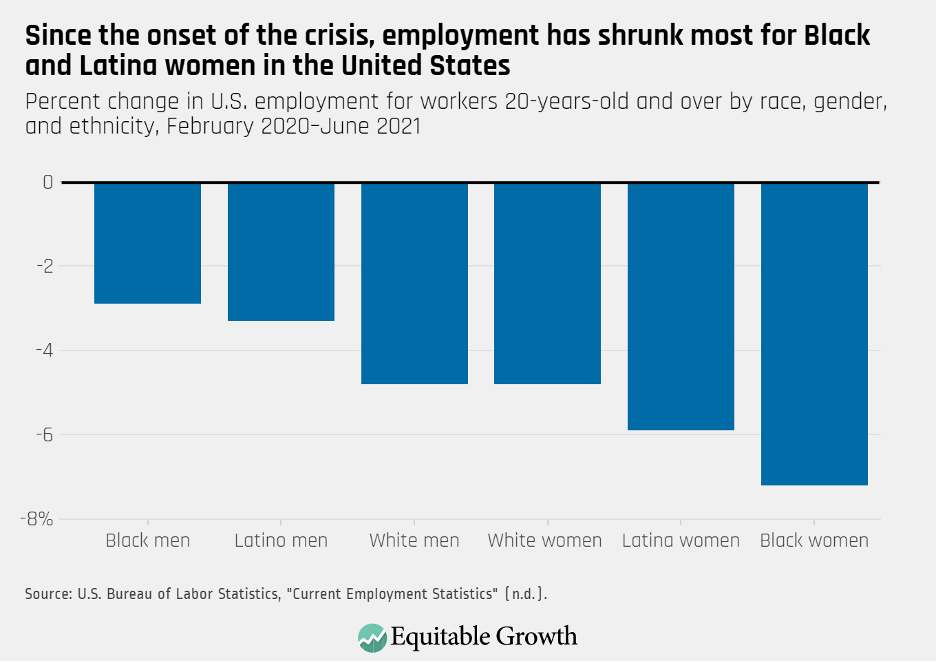

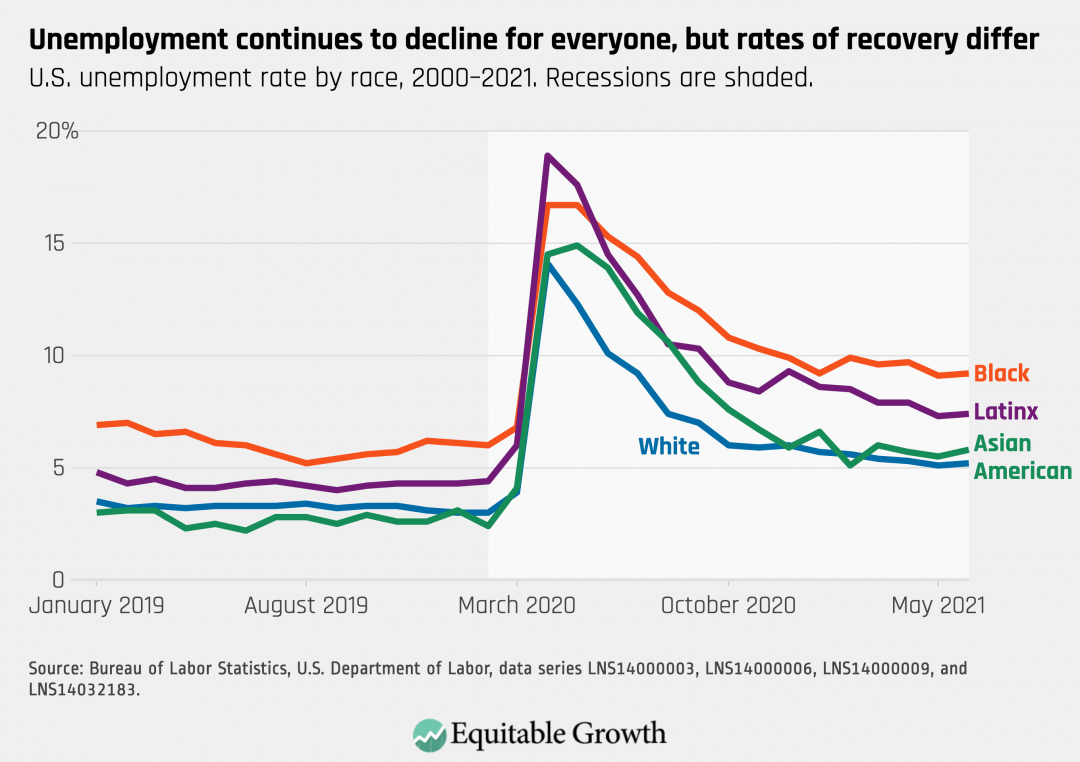

Secondly, structural inequities that were present in the U.S. economy well before the onset of the coronavirus recession—and then entrenched by it—mean that some of the labor market gains are not being experienced evenly across the lines of age, race, ethnicity, and gender. For instance, between the onset of the pandemic and June 2021, Black women’s employment has shrunk 7.2 percent—a deeper fall than for any other race-gender group.

Worker power and social infrastructure investments can power the U.S. economy toward economic growth that is strong, stable, and broadly shared

All in all, the path of the U.S. economic recovery is difficult to predict, not least because the coronavirus itself continues to mutate, and vaccine access and uptake varies markedly across states and counties. But as both employers and workers adjust in the aftermath of last year’s massive economic shock, robust wage growth in some sectors and a tightening labor market represent hopeful signs that after decades of declining worker voice, deliberate policy choices can continue to help increase worker bargaining power.

A tight U.S. labor market is a necessary condition for wage growth and good job matches. But without structural policies that promote worker power, today’s temporary gains will not translate into sustainable and broadly shared growth. Workers’ gains are the foundation of a strong recovery, so worker power helps build a robust U.S. economy.

While there is a lack of evidence that rising inflation and labor shortages are a true challenge for the U.S economy, these arguments nonetheless are being used for winding down policies that help achieve a more competitive labor market and for holding back much-needed investments in the U.S. social insurance infrastructure. Yet it is these very policies—investments in the Unemployment Insurance system, in high-quality child and elder care, and in paid sick and parental leave, for example—that are a foundation for sustainable economic growth.

Winding down current investments in social infrastructure prematurely or preventing their wider deployment amounts to a giveaway to low-road employers who would otherwise be unable to compete for workers. Employers need to meet the challenge of competing for workers instead of being handed options to take advantage of them.

Perhaps most immediately, reports that some employers are having trouble finding and hiring workers are driving states’ decision to opt-out of pandemic-induced and federally funded Unemployment Insurance expansions prior to their official expiration in September. The premature withdrawal from these programs, however, both hurts already-vulnerable workers and is unlikely to have any discernible effect on employment.

A recent survey by Indeed Inc., a popular job search platform, finds that among unemployed workers not urgently looking for jobs, fear about the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, security that stems from a spouse being employed or a financial cushion, and care responsibilities are much more commonly cited reasons for not engaging in an urgent job search than UI payments. In Missouri, officials say there has not been an increase in job applications since the state announced it would cancel the extra $300 in weekly benefits, which ended on June 12.

And arguments that quickly rising wages are both a symptom and a consequence of higher Unemployment Insurance benefits overlook important trends in the U.S. labor market. Indeed, relative to the previous two recessions, wage growth so far this year is not unusually strong. Particularly fast wage growth in the leisure and hospitality industry could, in part, reflect a return to the pre-pandemic trend or, an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute finds, the return of tipping.

More broadly, fears over so-called work disincentives ignore the evidence that worker power and social infrastructure programs promote economic efficiency. Economists Sandra Black at Columbia University and Jesse Rothstein at the University of California, Berkeley, for instance, propose that when workers cannot access healthcare or Unemployment Insurance benefits, the threat of financial hardship means they are more likely to remain in jobs that might not be a good match for them—a dynamic that can depress productivity and overall wage growth. During the COVID-19 crisis, income support from Unemployment Insurance sustained consumption. And analysis from the New York Federal Reserve Bank suggests that direct payments boosted the U.S. economy as well.

Disruptions to the U.S. labor market are an opportunity to achieve sustained worker power and economic growth

To ensure the U.S. labor market is competitive and the economy grows, the U.S. economy needs policies that ensure robust labor market protections, strengthen our system of income supports, invest in care infrastructure, and institutionalize worker power. Lifting the federal minimum wage, which has been stuck at $7.25 per hour since 2009, would boost pay for workers at the bottom of the income ladder and likely benefit workers of color and women of color in particular.

Similarly, for there to be a real restoration of workers’ bargaining power, it should also be easier for workers to join and form unions. There should be stronger protections for pro-union workers, and the right to organize and bargain collectively should be expanded to those who are currently excluded from many labor protections, such as independent contractors and agricultural and domestic workers. Reports that President Joe Biden plans to sign an executive order to ban or limit noncompete agreements—contracts that limit workers’ ability to switch to better, higher-paying jobs—would certainly be an important step toward a more dynamic labor market.

During the COVID-19 crisis, we relied on Band-Aid fixes to our nation’s income support programs, which helped prop up the economy during an unprecedented economic shock but do not address the shortcomings which prevent these programs from achieving their full potential to support the economy. Exclusionary eligibility requirements, application processes that are purposefully difficult to navigate, and insufficient benefits in programs such as Unemployment Insurance, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program both hurt individuals and constrain economic growth and stability. Research shows that these shortcomings disproportionately affect Black workers. For instance, states where a larger share of the population is Black tend to have lower levels of benefits under the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families than those where a smaller share of the population is Black.

Finally, to ensure that people with caregiving responsibilities can fully participate in the labor market, we need adequate care infrastructure. This means introducing a new federal income support program—paid family and medical leave—which research indicates would increase labor force participation of the current generation of workers and strengthen the human capital of the next. It also means investing in a child care system that meets the needs of all working people with children and strengthening the provision of community-based services and supports for older adults and people with disabilities.

Far from being a threat to the current economic recovery, stronger labor market protections, improved income support programs, more robust care infrastructure, and greater worker power would help ensure that economic growth in the post-pandemic economy is strong, stable, and broadly shared. Rather than repeating the policy mistakes made during the aftermath of the Great Recession—when insufficient stimulus and austerity politics based on ideology instead of evidence translated into a slow jobs recovery and years of stagnant incomes for low- and middle-income families—U.S. policymakers should strengthen the social insurance and income support programs that protect the entire economy, power greater worker productivity, and set up workers for success now and into the future when another recession inevitably arrives.