Overview

Since the 1960s, both women and underrepresented minorities in the United States have obtained an increasing share of bachelor’s degrees and other advanced degrees in fields most associated with invention—the so-called STEM fields of science, technology, engineering, and math. Yet there has been no similar increase in patenting activity among these groups.

Download File

The implications of U.S. gender and racial disparities in income and wealth inequality at each stage of the innovation process

The reasons are multiple and varied, but the core problem is the continued discrimination experienced by disadvantaged minorities and women at every stage of the innovation process, from childhood and youth exposure and mentoring in the STEM fields to postsecondary educational barriers to advancement, and from discriminatory denials of patent applications to the lack of opportunity to participate in the development of patentable ideas in the technology workplace. Closing this gender and racial gap in the U.S. innovation process could increase U.S. Gross Domestic Product per capita by 2.7 percent.

This issue brief examines these problems faced by disadvantaged minorities and women across the arc of the innovation curve in U.S. society and the economy. The research in this area is only just beginning to bear substantial fruit, but the findings to date are encouraging ones for providing the evidence needed to support policy proposals to rectify the problems. The brief then closes with several proposed policy recommendations, among them better mentoring of students at all levels of education, better opportunities for advancement in academia and in patent recognition, and decisive action against gender and racial discrimination in the workplace.

The problem

The costs of misallocating talent in the U.S. economy are increasingly evident in the economics literature. In their 2013 paper “Why Don’t Women Patent,” economists Jennifer Hunt at Rutgers University, Jean-Phillippe Garant and Hannah Herman at McGill University, and David Munroe at Columbia University calculate the cost to GDP of not including more women and African Americans in STEM education. They show the gender gap among science and engineering degree-holders is due primarily to women’s underrepresentation in patent-intensive fields and patent-intensive job tasks. They also show that women with a degree in science and engineering accrue patents little more than women with other degrees, meaning that an increase in the share of women with science and engineering degrees will not substantially close this gender gap. They find that women’s underrepresentation in engineering and in jobs involving development and design explain much of the patent gap. Closing this gap could increase U.S. GDP per capita by 2.7 percent. One of the authors of this issue brief, Lisa D. Cook, and Yanyan Yang of the University of Massachusetts Boston came to similar conclusions concerning women and African Americans in their 2018 paper “Missing Women and African Americans, Innovation, and Economic Growth.”

In their 2018 research paper “The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth,” economists Chang-Tai Hsieh and Erik Hurst at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and Charles I. Jones and Peter Klenow at Stanford University analyze the gender and racial distribution for highly skilled occupations over the past 50 years. They show the change in the occupational distribution since 1960 suggests that a substantial pool of innately talented women and African Americans in 1960 were not pursuing their comparative advantage, and this misallocation of talent affects aggregate productivity in the economy. They find one-quarter of growth in aggregate output from 1960 to 2010 can be explained by an improved allocation of talent.

Whatever the source of disparity, these gender and racial disparities exist at each stage of the innovation process, from education to training, and from the practice of invention to the commercialization of invention, and can be costly to the U.S. economy. These disparities can also lead to increased income and wealth inequalities at each stage for those who would otherwise participate in the innovation economy. Let’s look at each stage to assess this problem in further detail.

Education and training

In the early stages of postsecondary education and training in STEM fields, women and underrepresented minorities lag in participation in nearly each STEM field. This is first evident in the awarding of bachelor’s degrees. Even though a higher proportion of total degrees were awarded to women in 2014, women were awarded only 35 percent of the degrees in STEM fields. For advanced degrees, women outnumber men in some STEM fields. In 2016, women received 53 percent of the doctoral degrees in biological science and 71 percent of doctoral degrees in psychology. In other STEM fields, they are barely present. In 2016, women received 23 percent of doctoral degrees in engineering, 17 percent to 18 percent of those in computer science and physics.

The recent literature on the gender and racial gaps related to participation in STEM fields attempts to identify the factors affecting these differences. In “The Math Gender Gap: The Role of Culture,” Natalia Nollenberger at the Instituto de Empress SL, Nuria Rodríguez-Planas at the City University of New York, and Almundena Sevilla at Univeristy College London analyze the math test scores of the children of immigrants to the United States. They find that immigrant girls whose parents come from more gender-equal countries perform better than those whose parents come from less gender-equal countries, showing the transmission of cultural beliefs on the role of women in society contributes to the math gender gap.

Economists Alexander Bell and Raj Chetty at Harvard University, Xavier Jaravel at the London School of Economics, Neviana Petkova at the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and John Van Reenen at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology present evidence in their 2019 paper “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation” that suggests that gender and race gaps in children’s chances of becoming an inventor in the United States may be primarily driven by differences in environment. They show that exposure to innovation as a child has a significant causal effect on whether the child becomes an inventor. The five co-authors suggest there are many “lost Einsteins” resulting from this lack of exposure to innovation in childhood.

Other recent papers attempt to identify other salient factors and outcomes associated with gender and racial differences in STEM participation, among them the impact of social norms and gender stereotypes, as well as professors’ gender, on test scores and college majors. In their 2018 paper “Nevertheless She Persisted? Peer Effects in Doctoral STEM Programs,” economists Valerie Bostwick and Bruce Weinberg at The Ohio State University focus on gender peer effects and attrition among women in STEM doctoral programs. They show that gender peer effects are the largest in programs that are typically male-dominated, finding that women entering cohorts with no female peers are less likely to graduate within 6 years and also more likely to leave after the first year of a Ph.D. program.

Other recent social science literature focuses on factors affecting participation in STEM education beyond the STEM doctoral pipeline in the form of supply constraints. For instance, Indiana University’s Elizabeth Canning, Katherine Muenks, Dorainne Green, and Mary Murphy show in their new paper that STEM faculty who believe ability is fixed are associated with higher racial achievement gaps among their students.

The practice of invention

STEM occupations have higher wages and stronger job growth than non-STEM occupations in the United States. The national average wage for all STEM occupations was $87,570, compared to the national average wage for non-STEM occupations of $45,700. Employment in STEM occupations grew by 10.5 percent between May 2009 and May 2015, compared to 5.2 percent in non-STEM occupations.

In the process of practicing invention and creating new knowledge or products, women and African Americans not only engage at generally lower rates than their counterparts but also earn less and are employed less than their counterparts. In 2015, the median salary for African Americans was only 79 percent of that for whites. While the median salary for men in the innovation economy in 2015 was $87,000, it was $62,000 for women, which was 71 percent of the median male salary. Among scientists and engineers, African American unemployment in 2017 was 4.3 percent, compared to 2.1 percent for whites.

While U.S. employment rates are increasing among women and underrepresented minority scientists and engineers, unemployment rates vary significantly by gender and racial and ethnic group. The unemployment rate for African American women is higher than the unemployment rate for all scientists and engineers, is nearly double that of all scientists and engineers, and is more than double that of white women scientists and engineers. Unemployment for underrepresented minority men, at just above 4 percent, is higher than for white and Asian men and higher than the average for all scientists and engineers.

The literature on gender and racial differences in the inventive process has evolved similar to the literature on STEM participation. The older literature focused on identifying the gaps, while the newer literature focuses on sources or correlates and outcomes. A few papers in the past decade have focused on the misallocation of talent among inventors and other high-skilled workers. One of the authors of this issue brief, Lisa Cook, and her co-author at Michigan State University, Chaleampong Kongcharoen, found that co-ed patent teams are more productive (at commercialization) than single-sex male or single-sex female patent teams.

Similarly, in “Why Don’t Women Patent,” Rutgers’ Hunt and her co-authors investigate the gender gap for commercialized patents. Using the 2003 National Survey of College Graduates, they show the gender gap among science and engineering degree holders is due primarily to women’s underrepresentation in patent-intensive fields and patent-intensive job tasks. They also show that women with a degree in science and engineering file patents little more than women with other degrees, meaning that an increase in the share of women with science and engineering degrees will not substantially close this gender gap. They conclude that women’s underrepresentation in engineering and in jobs involving development and design explain much of the patent gap.

Closing this gap could increase U.S. GDP per capita by 2.7 percent. Research by Cook and Yang executes a similar exercise using more recent data, finding that GDP per capita would be 0.6 percent to 4.4 percent higher if more women and African Americans received STEM training and worked in related jobs.

Commercialization of invention

In the final stage of commercializing invention, outcomes are starkly different. This is the stage where incomes can be high, and wealth generated can be substantial. This is immediately apparent when considering the prominence of tech firms in the most valuable public firms and the relative size of these firms. The trillion-dollar valuations of some tech firms—among them Amazon.com Inc., Apple, Inc., and Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit—put them roughly on par with the Gross National Product of the Netherlands, Mexico, or Australia. Five of the top 10 wealthiest people in the world derive their wealth primarily from the innovation economy, according to Forbes’ global wealth rankings. And nine technology firms with initial public offerings in the United States last year were valued at roughly $37.5 billion, with the most valuable one, Snap Inc., valued at more than $20 billion.

The number of tech billionaires also is growing. Daniel Ek, the 35-year-old co-founder and CEO of music streaming company Spotify Technology S.A. taught himself to write code in his early teens and started his first business when he was 14. In April 2018, when Spotify went public, the Swede became the tech industry’s newest billionaire. On the close of the first day of trading, the company was valued at more than $26 billion, with Ek’s share worth nearly $2.5 billion. Tech entrepreneurs continue to dominate the list of the world’s billionaires. In the first half of 2018, 11 new tech entrepreneurs became billionaires when companies they founded went public, were acquired, or had new funding.

This is also the stage of the innovation process where the outcomes are most unequal by gender and race. Women are only 8 percent of new hires at venture capital firms. Female CEOs receive only 2.7 percent of all venture funding, while women of color get virtually none: 0.2 percent. Women and African Americans are often found in legal and marketing departments but are largely missing in technical positions and among executives and boards.

In 2014, Fortune ranked several large tech firms based on recently released demographic data. With respect to women executives, one firm was ranked highest, with women constituting 43 percent of leadership roles, and two firms were ranked lowest, with women filling 19 percent of these roles. Women constituted just 18.7 percent of boards of companies in the Standard & Poors 500 in 2014, which was up from 16.3 percent in 2011. In 2015, 11 percent of venture capitalists were women, and 2 percent were African American.

This is the stage where gender and racial gaps have been covered the least in the academic literature. Cook and Kongchareon’s 2010 research and Cook and Yang’s 2018 paper include systematic analyses of commercialization of invention by race and gender, but, case studies in the business literature notwithstanding, this is typically not the focus of academic inquiry.

Policy efforts underway

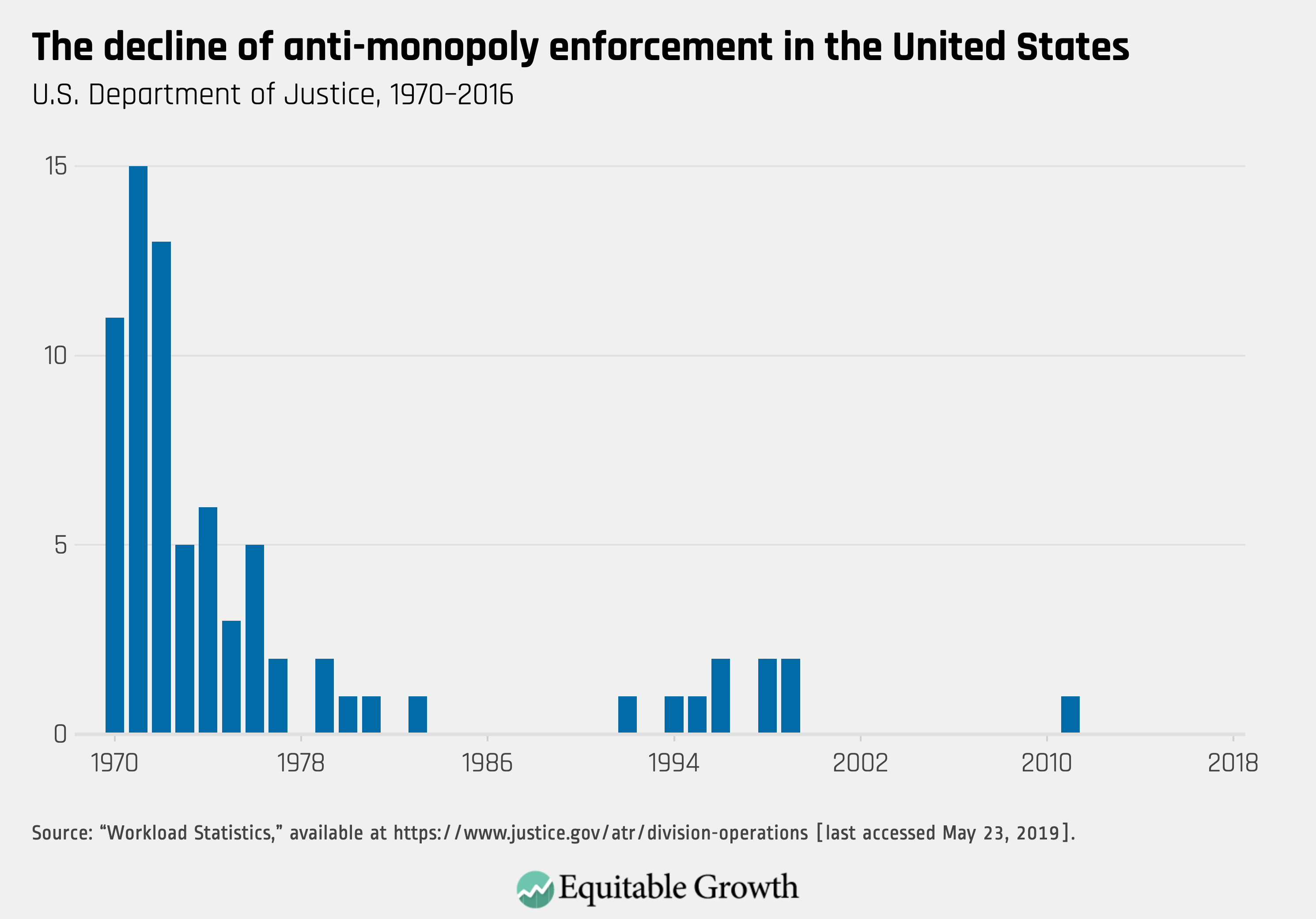

The potential losses to individuals and to the U.S. economy as a whole due to these gender and racial gaps in the innovative process will not close any time soon. The patent gap, for example, is estimated to close only by 2092. Not surprisingly, then, economists and policymakers are increasingly expressing concern about improving the participation of women and underrepresented minorities in the innovation economy.

In the current session of Congress, the SUCCESS Act was introduced in the House of Representatives (H.R.6758) by Rep. Steve Chabot (R-OH) and the Senate by unanimous consent and became law after President Donald Trump signed it into law on October 31, 2018. The objective of the bill is to obtain information from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office about the ability of the agency to measure the dimensions of this patenting problem and figure out how best to identify women and underrepresented minorities in the data. In February 2019, the Patent Office released a report on the history and status of women receiving patents. Over the past few decades, the share of patent inventors who are women has increased, yet key differences between female and male inventors persist.

In 2019, a new companion bill, the Inventor Equality and Diversity Act of 2019, is being proposed by the House Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet of the House Committee on the Judiciary. This bill would provide mechanisms to collect demographic data during the patent application process. These data would be collected separately from other data related to the patent application and would be voluntarily submitted to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

If this bill passes, then its provisions would go a long way to improve how inventors are identified in the data. Currently, algorithms identify demographic characteristics based on probabilities, while the current bill would obtain more reliable and consistent data. Having better data could aid researchers in doing such analysis and aid economic policymakers in improving the living standards of all Americans.

Apart from comprehensive data collection by an independent federal agency, further efforts are needed to make the innovation economy inclusive. Such issues include mentoring, exposure to invention, blind patent review, and workplace climate. We briefly look at each of these features in turn below.

Mentoring

Mentoring has been broadly suggested as one tool to address the gender and race gap in STEM careers. As aforementioned, Harvard’s Chetty and his co-authors show that the income, race, and gender gap in invention is primarily due to environmental barriers in acquiring human capital, including a lack of mentoring and exposure to careers in science and innovation in childhood, and not due to differences in ability.

The American Economic Association launched a summer boot camp program in the 1970s to increase racial and ethnic diversity in the economics profession. Mentoring is a key component of this program. A 2014 research paper estimated the effectiveness of the AEA’s summer program, finding that program participants were more than 40 percentage points more likely to apply to and attend a Ph.D. program in economics, 26 percentage points more likely to complete a Ph.D., and about 15 percentage points more likely to work in an economics-related academic job. According to these estimates, the summer program may directly account for 17 percent to 21 percent of the Ph.D.s awarded to minorities in economics over the past 20 years.

The effectiveness of mentoring is recognized beyond academic papers and university programs, with programs designed to make a difference. US2020, an organization focused on programming that supports underserved and underrepresented primary and secondary school-age students, has a mission of changing the trajectory of STEM education in the United States by dramatically scaling the number of STEM professionals engaged in high-quality STEM mentoring with youth. US2020 is building a community of companies, organizations, schools, government agencies, and cities to participate in mentoring, encouraging our society to imagine 1 million science, technology, engineering, and math professionals mentoring students in Kindergarten through graduate school.

Encouraging invention at an early age

Exposing children to invention and innovation is becoming more recognized method of increasing participation. Just one case in point is Spark Lab at the Lemelson Center for Invention and Innovation at the Smithsonian Institution, which provides an activity space that allows children to create an invention and to help them think about making the invention useful. Targeting low-income, underrepresented minorities, and female children for such activities is recommended by authors Chetty and his co-authors, among others.

Blind patent review

A recent paper in Nature finds that, all else being equal, patent applications with women as lead inventors are rejected more often than those with men as lead inventors. An easy fix would be for the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to engage in the blind review of patent applications by patent examiners. Research by Princeton University economist Cecilia Rouse and Harvard University economist Claudia Goldin has demonstrated the success of blind reviews in increasing the representation of women in the context of symphony orchestras.

Workplace climate

Workplace issues for women and minorities go beyond the opportunity to participate in invention and innovation. Other issues have been brought into stark relief by recent events related to workplace climate, such as recent protests and discussions at Google and at Microsoft Corp. over an array of discrimination complaints. Among the issues identified in the case of these two firms—ones that have been reported about in similar workplaces elsewhere in U.S. technology industries—is the lack of transparency when dealing with these complaints (including forced arbitration for sexual harassment claims), discriminatory workplace cultures, and pay and promotion inequality.

Most patented invention occurs at firms. Therefore, at public companies, shareholders and the boards of directors need to hold CEOs more accountable for the workplace climate at their firms. The shareholders and boards of private companies should do the same. Congress could also play a role in bolstering the ability of the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to investigate such complaints and help to minimize the frequency and intensity of hostile workplaces for women and underrepresented minorities.

About the authors

Lisa D. Cook is an associate professor in the Department of Economics and in International Relations at James Madison College at Michigan State University. She is a member of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s Research Advisory Board.

Janet Gerson is a lecturer emerita of economics at the College of Literature, Science and the Arts at the University of Michigan.