(This opinion piece first appeared in Morning Consult on July 9, 2019)

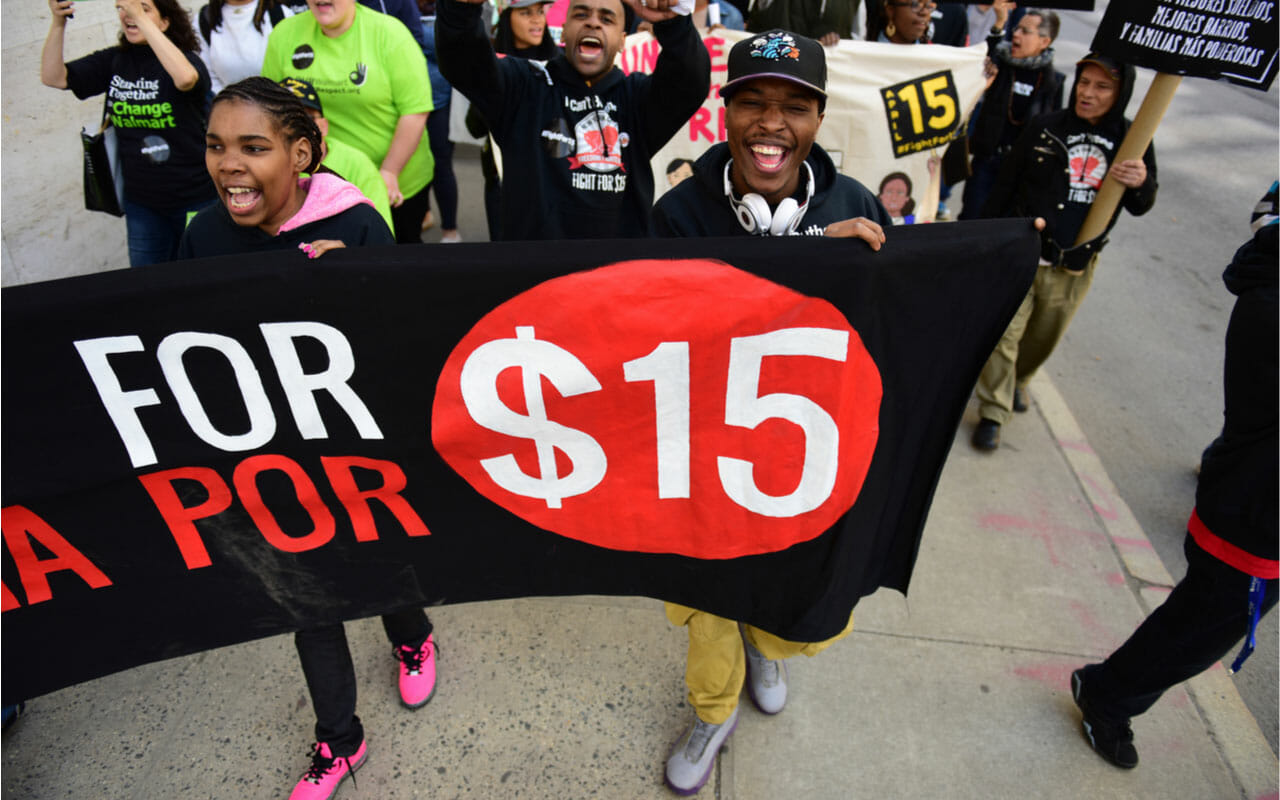

Policymakers opposed to raising the federal minimum wage above $7.25 per hour have long argued it would lead to significant job losses. Some of those same opponents will now likely use a new Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of the proposed minimum wage legislation currently before Congress to argue against passing it.

Their claims — and to a large degree, CBO’s analysis — are rooted in flawed theoretical foundations and outdated research. Sophisticated research methods from multiple studies show no job losses, or virtually none, result from raising the minimum wage. These studies also draw from previously unavailable empirical methods, which CBO did not fully account for in its own analysis.

How long has it been since we last increased the minimum wage? Nearly a decade, which is the longest interval without an increase since the minimum wage was created more than 80 years ago.

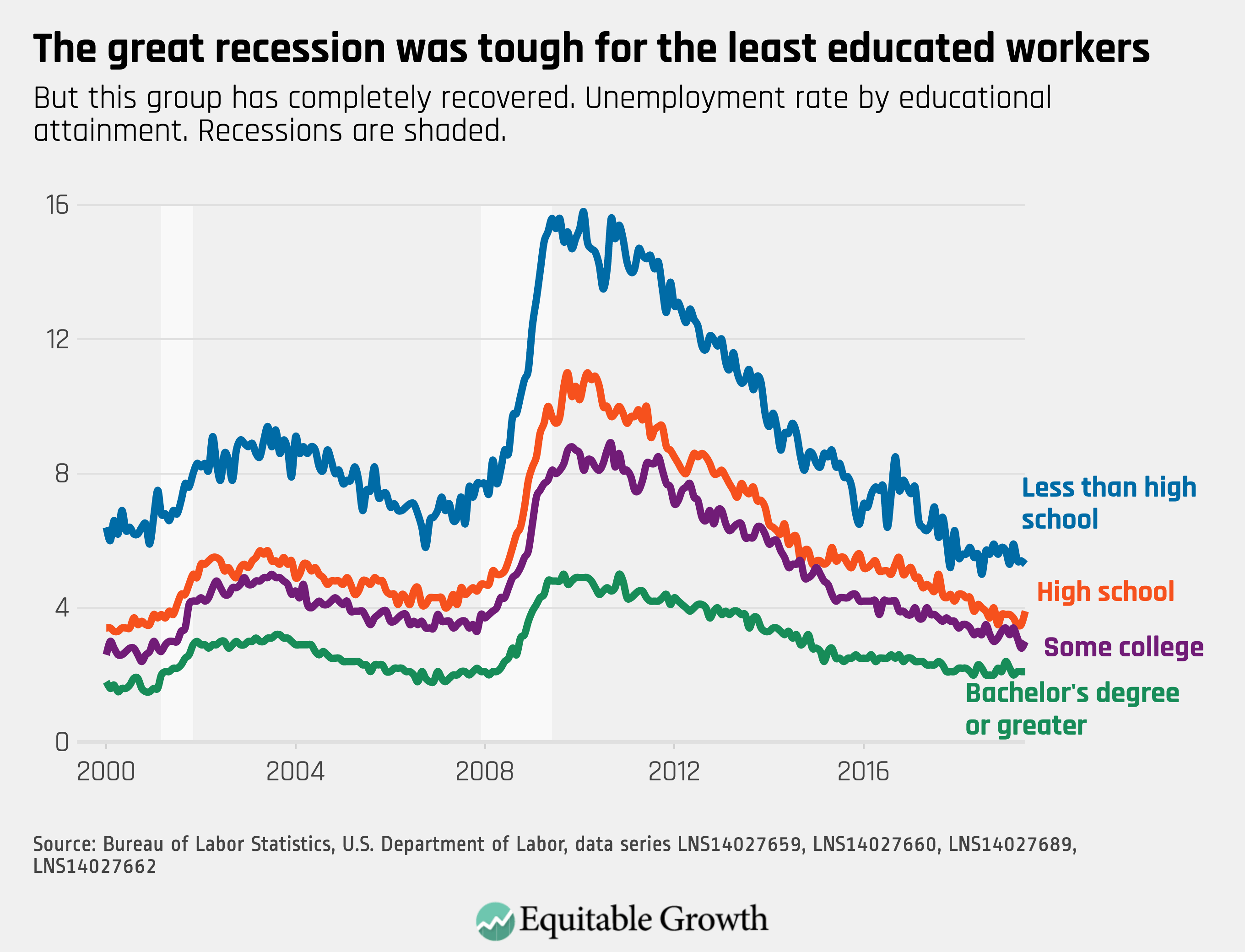

Despite Congress’ inaction, 24 states and the District of Columbia have increased their minimum wage since 2009, when the last federal increase occurred. This has provided an opportunity for researchers to conduct modern, sophisticated empirical analyses to determine the specific impact of these increases on wages, incomes over time and employment. Specifically, researchers have compared individuals over time in states, cities and counties that have increased their minimum wage to those who have not been exposed to a minimum wage increase. Now we can move past guesses about how individuals or businesses might react to policy changes and observe how they actually behave.

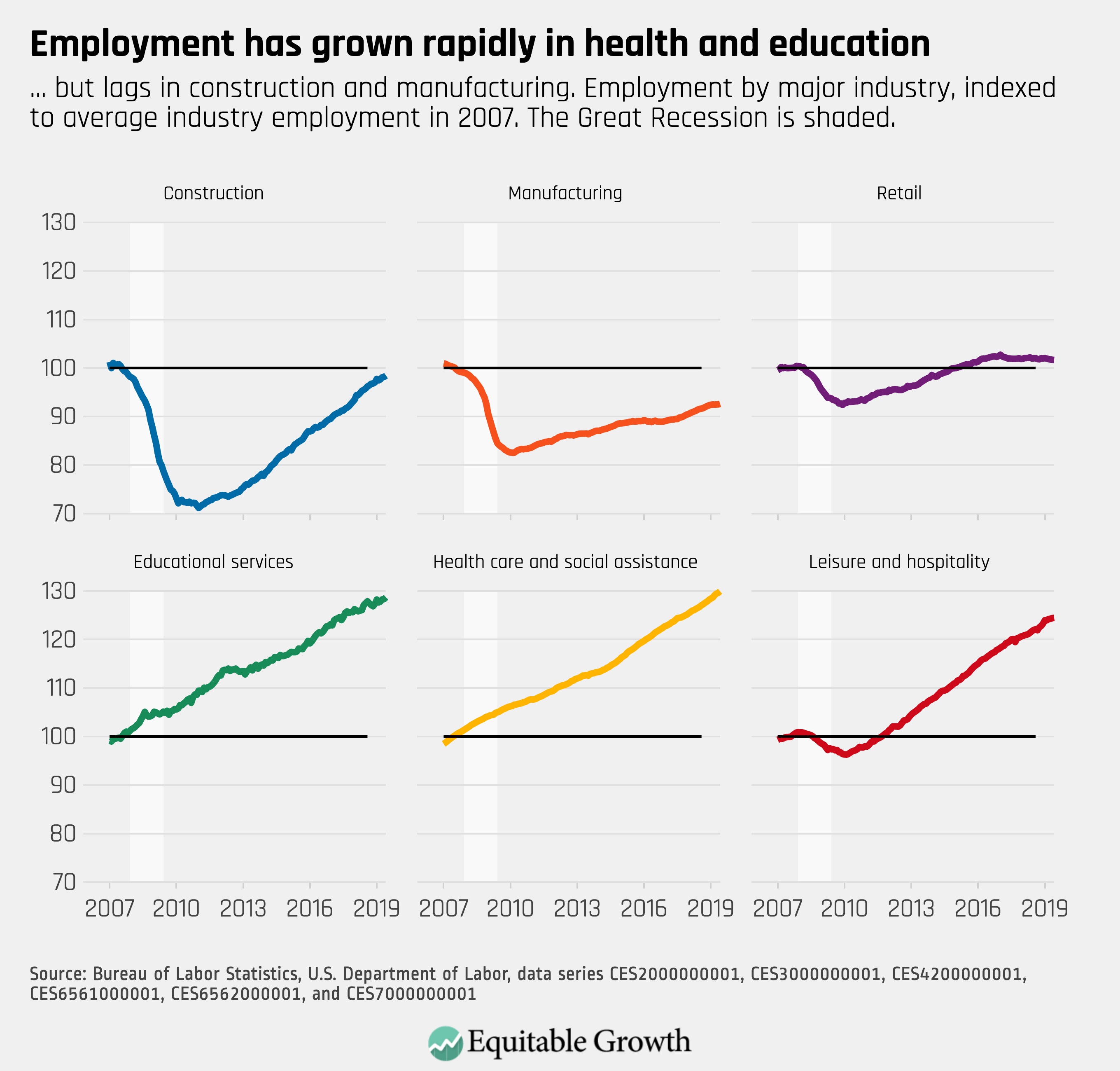

In the largest and perhaps most important recent study in 2018, researchers examined six U.S. cities, all of which have minimum wage levels above $10 per hour. The study, which focuses on the food industry because of its high proportion of minimum-wage or near-minimum wage workers, found that low-income workers’ earnings rose significantly following an increase in the minimum wage. In those cities, they observed between a 0.3 percent decrease to a 1.1 percent increase in food industry jobs. This stands in contrast to the CBO finding that raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour would cost 1.3 million jobs.

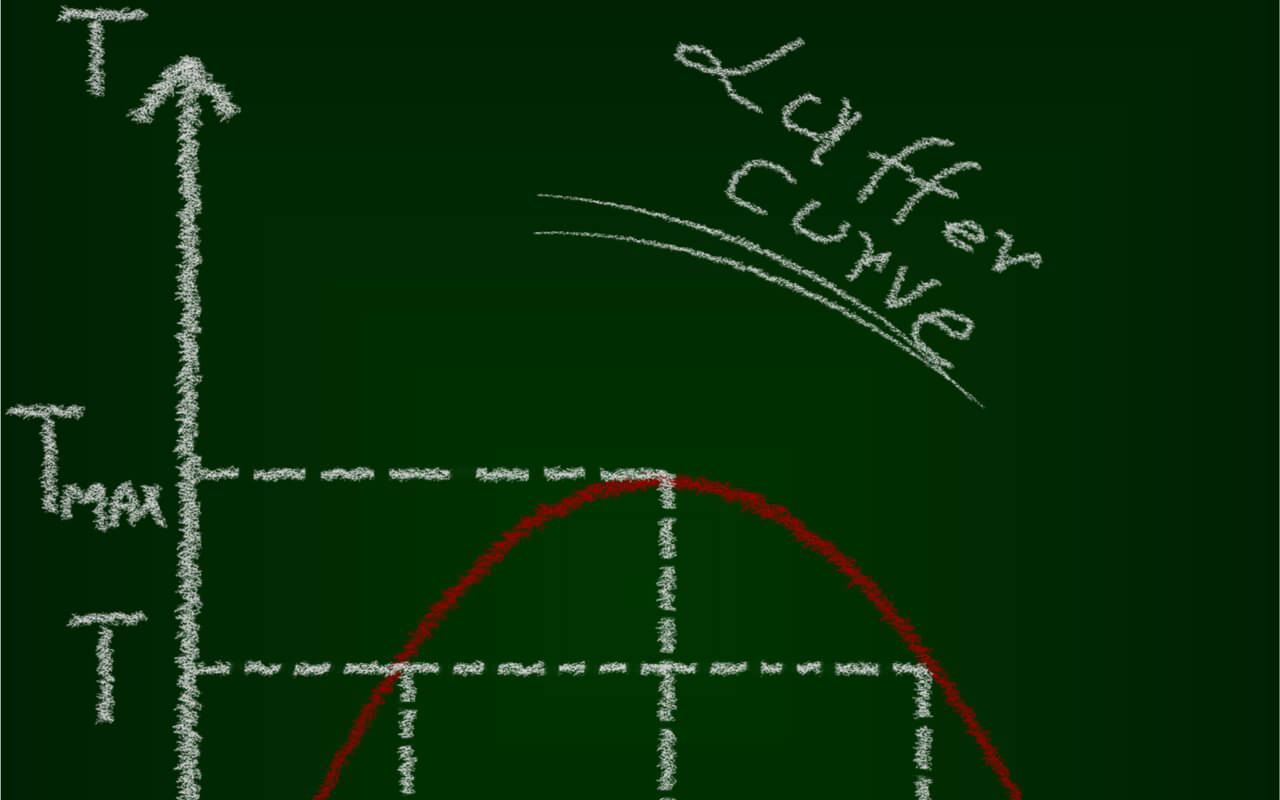

In other words, the research finds there is quite a bit of room for wages to rise without causing significant job losses. One reason for this may be monopsony power, where wages are suppressed to a lower level than the value workers contribute, and which employers are able to exploit throughout much of the U.S. economy. Perhaps in part because of this, workers over the past few decades have been receiving a smaller and smaller share of national income. In the case of monopsony, statutorily increased wages correct for a lack of competition.

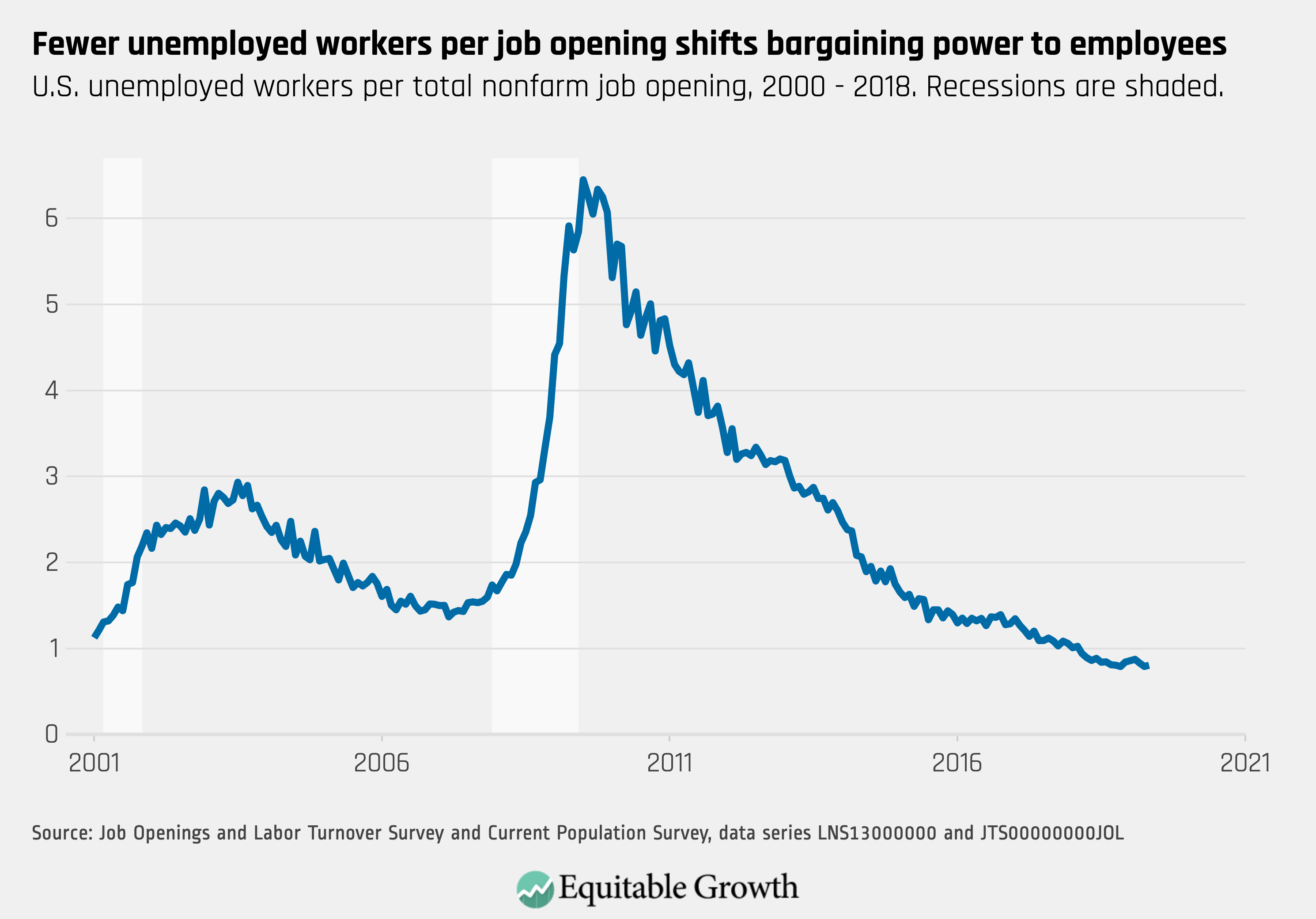

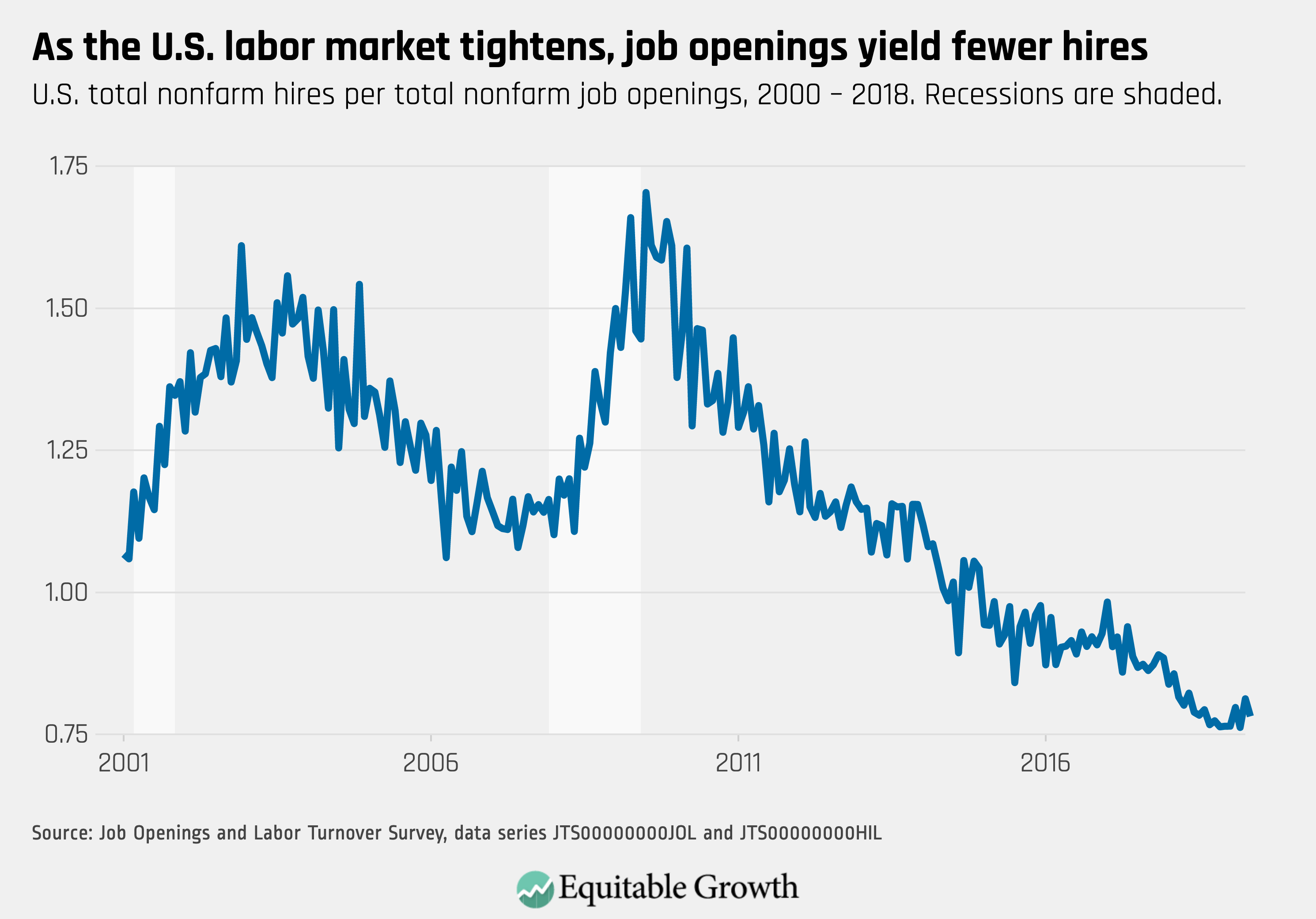

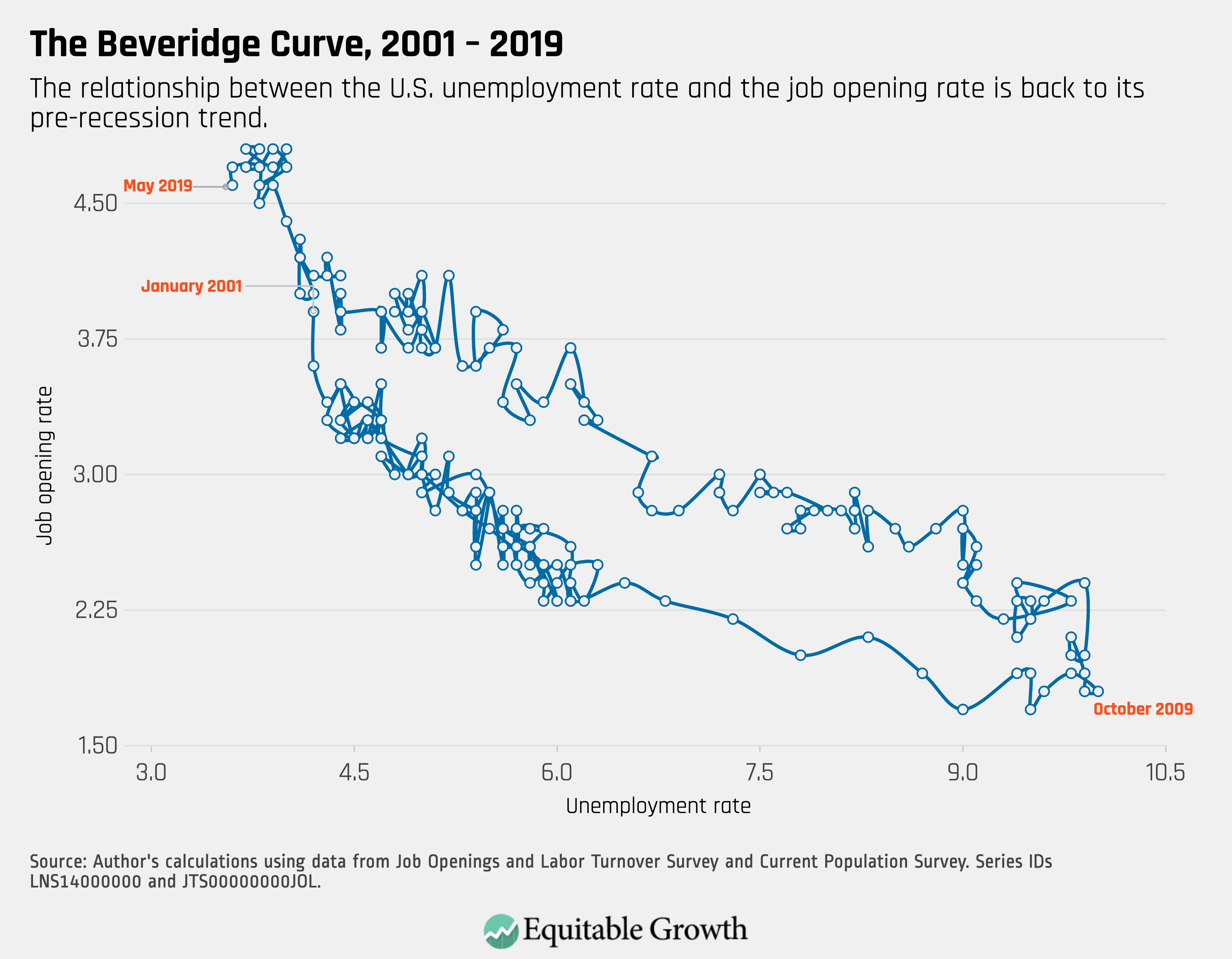

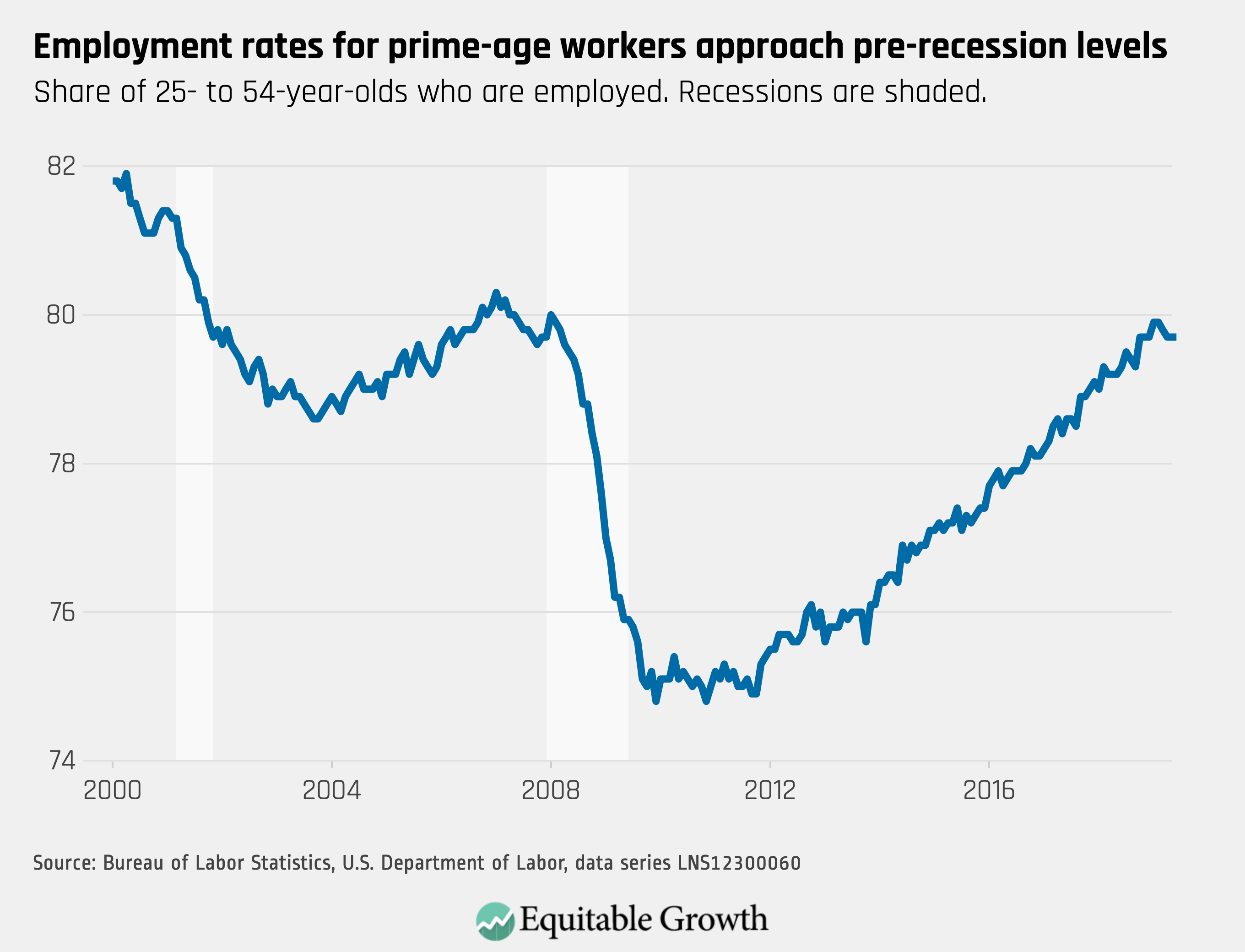

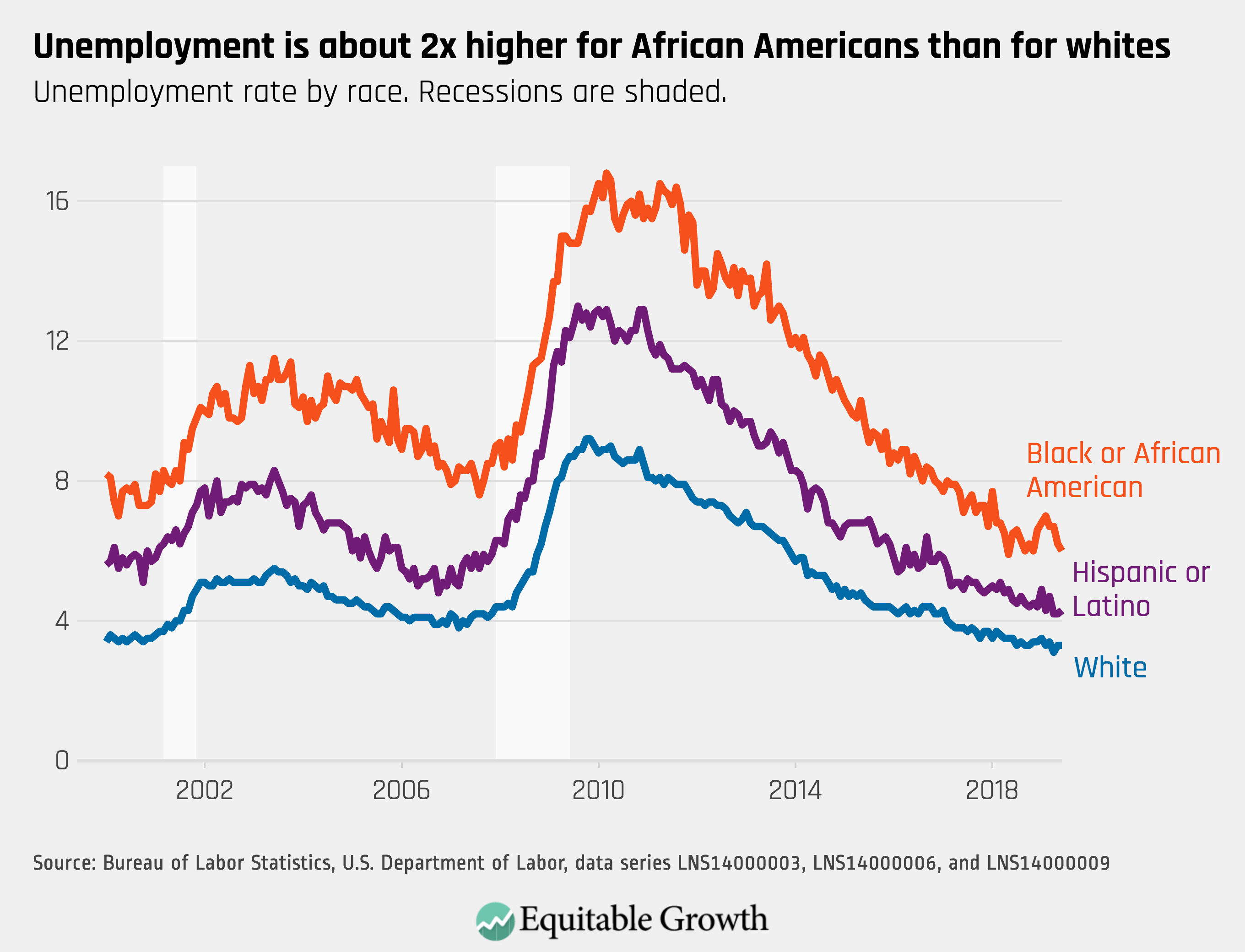

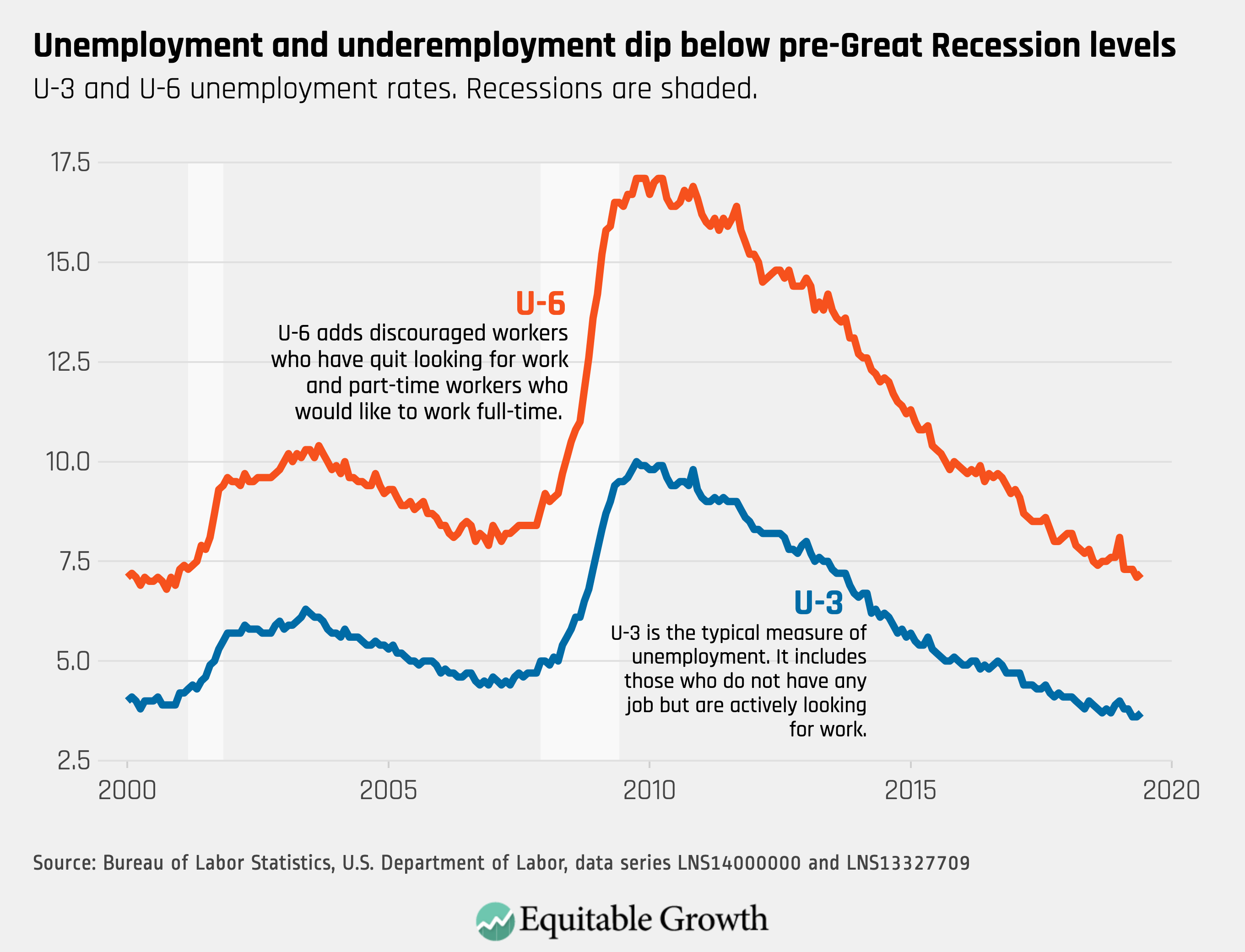

Another reason is the long economic recovery with the still-tightening labor market — though unemployment remains historically low and corporate profits are high, wages have not kept pace as economists would expect at this point in the recovery. One thing is clear: Businesses can well afford to pay their workers higher wages.

The CBO report confirms that an increase to $15 per hour would raise wages for 27 million workers. Even with the too-high estimate of job losses, the positive effect of boosting wages overpowers any negative effect from job losses for poor households. CBO confirms that families below the poverty line would see a 5.3 increase in income, lifting 1.3 million families out of poverty.

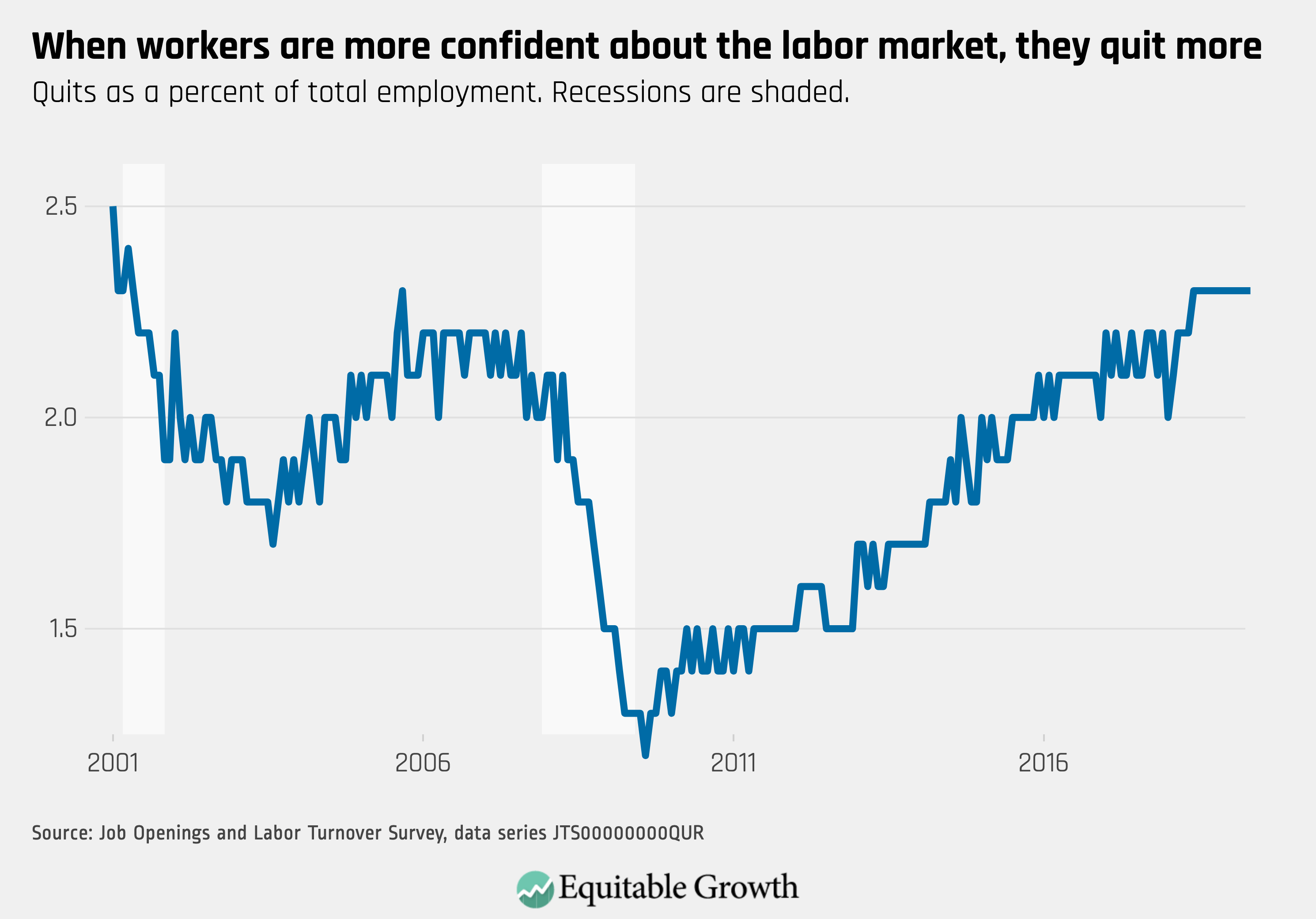

In general, the mere fact of job losses does not disqualify a minimum-wage increase from being a good policy for workers and the economy. Congress needs to balance the overall impact on earnings and family well-being against any effect on jobs. As economist David Howell has written, policymakers must consider all the benefits of a higher minimum wage — not only the increased income for workers and families, but also lower turnover, which leads to higher productivity, for example — with the possible costs. Especially in today’s tight labor market, there is a long way to go before any increase is likely to be accompanied by meaningful job losses.

Low-wage workers deserve to earn a living wage that enables them to support their families. Raising the federal minimum wage would not only help the economic recovery to continue, it would also help address systemic economic inequality at levels not seen since the 1920s. A significant minimum wage increase is past due.