The lagging wages of workers in the United States is one of the most significant economic trends of the past several decades. Even with some signs of revival, wages are still lower than they were a decade ago. It is increasingly clear that increasing market concentration (“monopsony power”) and reduced labor union clout have played key roles in this decline of worker bargaining power.

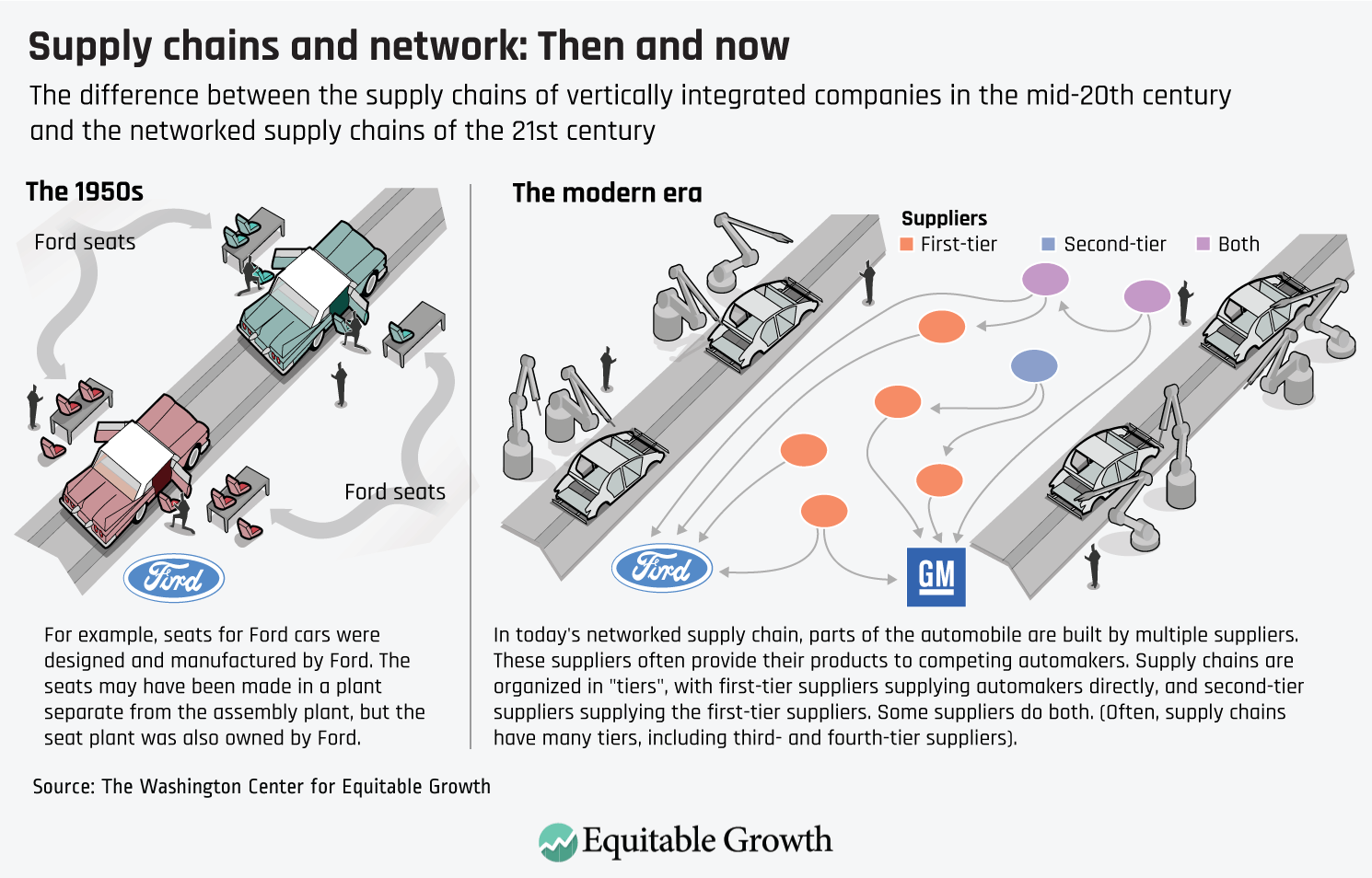

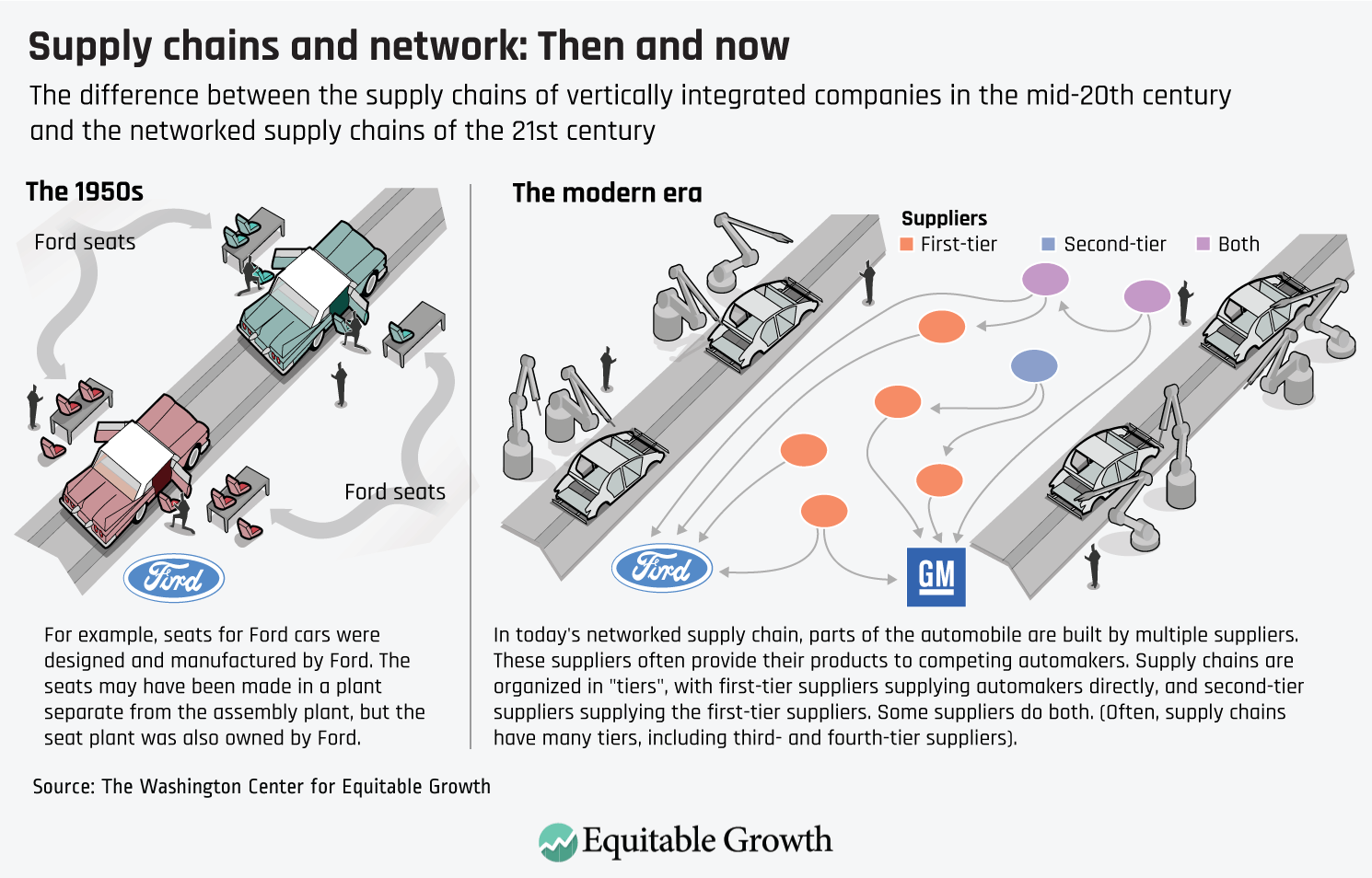

But another important reason for stagnating wages is the outsourcing of work during this same time period. Large firms shifted from doing many activities in-house to buying goods and services from a complex web of other companies. These outside suppliers manufacture components and provide services in areas such as logistics, cleaning, and information technology. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Some of this restructuring contributes to innovation. As final products have become more complex, it makes sense for large firms to purchase key components from firms that specialize in that technology or process. Supply networks based on product specialization do not necessarily reduce wages and could have the opposite effect.

But in other cases, firms outsource so as to offload production onto firms with weak bargaining power. These firms have little ability to compete except by aggressively holding down wages. David Weil has called this kind of separation of product markets and labor markets “fissuring.” This “low-road” model for the U.S. economy has weakened innovation and suppressed wages, and is contributing to the erosion of U.S. workers’ standard of living.

Decisions about how to structure supply chains matter greatly for working Americans, yet this topic rarely takes a front seat in discussions of policies to address income inequality. To remedy this oversight and stimulate equitable growth, policymakers must understand how the economic pie is created—not just how it is divided. Because of the size and importance of supply chains to the U.S. economy, their structure and governance are key determinants of the viability of efforts to improve job quality.

Overall, domestic U.S. firms purchase intermediate inputs equal to about 50 percent of their overall output, while intermediate outputs comprise 75 percent of the output of U.S.-based multinationals. Because of deregulation, market failures, and corporate policies, the providers of these intermediate goods are often small, weak firms that compete by cutting corners on existing products and processes and thus innovate less and pay less.

Low-road outsourcing is found in services such as payroll, janitorial work, and security, and now includes “employment activities that could be regarded as core to the company: housekeeping in hotels; cooking in restaurants; loading and unloading in retail distribution centers; even basic legal research in law firms,” as Weil has written. Some of these workers are in “alternative” forms of employment, such as independent contractors (whose work is often, in fact, overseen in quite a lot of detail by the employing firm, as at the giant shipping firm FedEx Corp.), temporary help, or other forms of gig work. A related phenomenon occurs when franchisors (for example, the fast food giants) use their market power to impose restrictions on their franchisees that result in suppression of wages. But much of the employment is in full-time, year-round employment—just at low wages and low benefits.

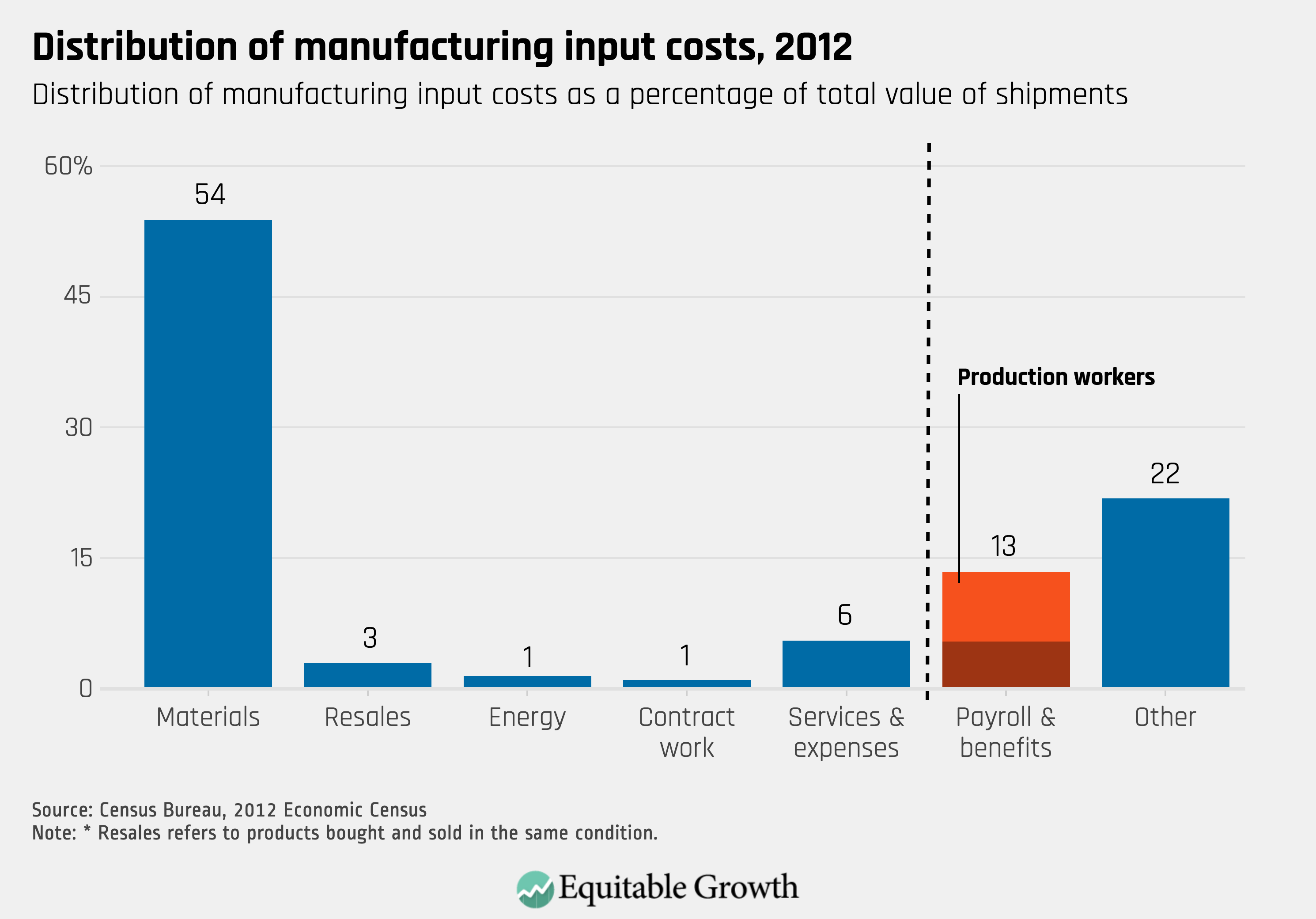

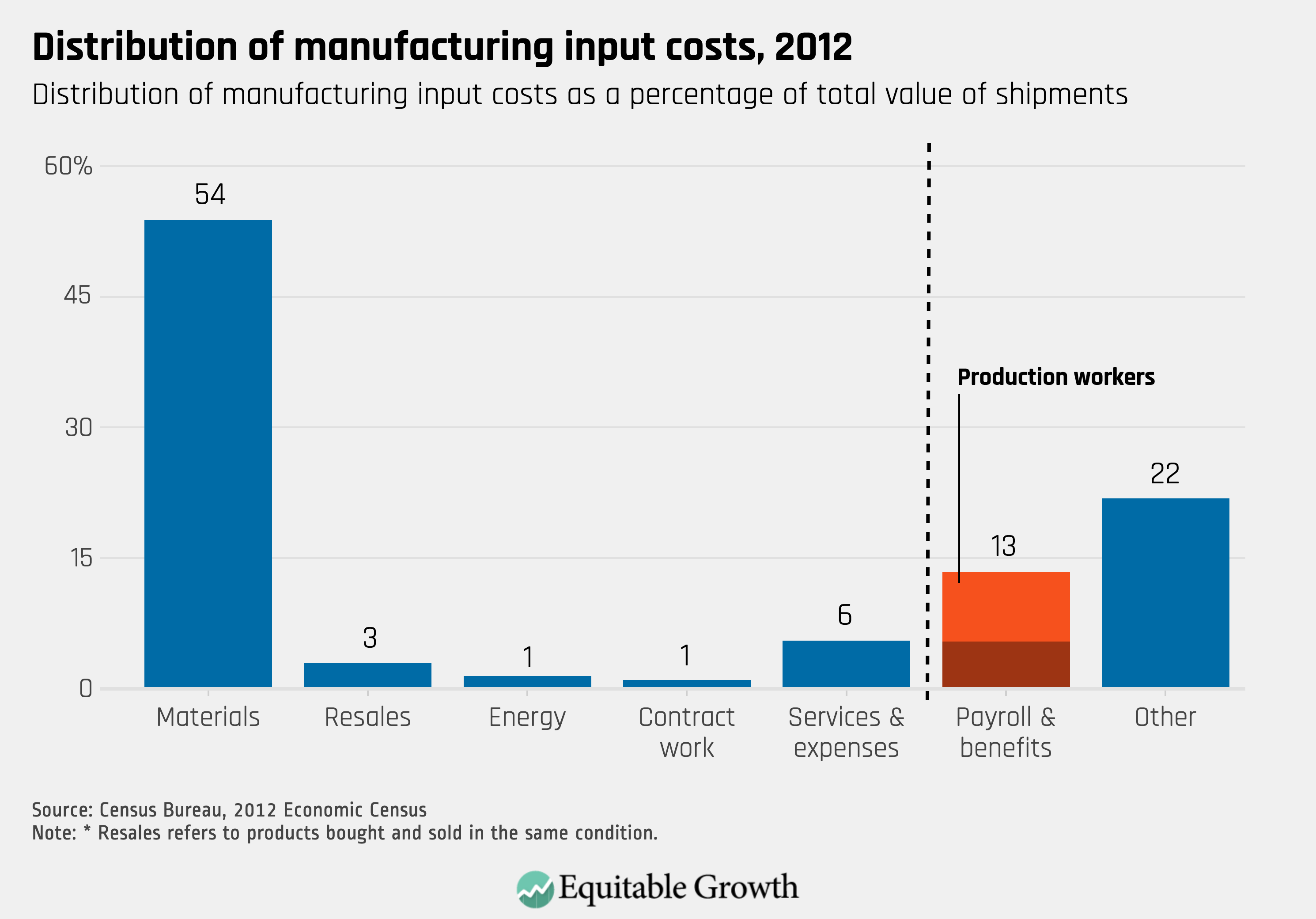

In manufacturing, supply chains made up of independent firms are now the largest driver of manufacturers’ costs, as detailed in Figure 2. Firms with fewer than 500 employees are an increasing share of manufacturing employment, accounting for 42 percent of such workers in 2012. These small firms struggle at each phase of the innovation process. They are only 15 percent as likely to conduct research and development as large firms. Small firms also struggle to obtain financing and a first customer to help them commercialize a new product or process. Finally, small manufacturers have trouble adopting new products or processes developed by others, due to difficulty in learning about and financing new technology. As a result, small manufacturers are only 60 percent as productive as large firms. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

These forms of outsourcing of employment, especially as carried out in the United States, typically create undesirable outcomes for workers in areas such as wages, benefits, job security, and safety. Job quality is typically lower at suppliers than at lead firms because of the barriers to innovation discussed above, which reduce productivity; the absence of pressures to reduce wage differentials within a firm due to norms of fairness; and greater pressure on wages at outside suppliers, which are more easily replaced than are internal divisions.

If purchasing firms focus only on price per unit, one of the few profit-making strategies available to firms lower down the chain is to keep wages as low as possible. Even though investments might yield productivity improvements, such firms often don’t make them because they lack the capability to do so or would not capture much of the benefit due to fierce competition. Their customers are often unwilling to help because some of the profits from implementing those processes might accrue to the supplier’s other customers, including competitors. This keeps workers in low-skill, low-wage positions and, because this model prevails through much of the U.S. economy, contributes to lagging wages nationally.

A different kind of outsourcing is possible—“high-road” supply networks that benefit firms, workers, and consumers. Under this model, there is greater collaboration between management and workers and along the length of the supply chain, sharing of skills and ideas, new and innovative processes, and, ultimately, better products that can deliver higher profits to firms and higher wages to workers.

Firms could take a key step by themselves, since it could improve profits. Collaboration among firms along a supply chain can lead to greater productivity and innovation. Lead firms can raise the capabilities of supplier firms and their workers such that even routine operations can benefit from collaboration for continuous improvement. By breaking down the usual silos within and between firms, they can ensure that workers along the chain are exposed to ideas and training to the ultimate benefit of all. Companies can, on their own, offer suppliers assurance that they will receive a fair return on their investments in new technologies and in upgrading their capabilities. Firms also could promote information-sharing and make changes based on suppliers’ suggestions. And firms could use a total-cost-of-ownership approach in their own purchasing decisions, adopting a holistic perspective on supplier companies rather than relying on price-per-unit alone.

Yet a variety of market failures prevent many firms from fully adopting these and other policies on their own, which is why public policies are needed to realize this vision. Government policies and actions to promote supply chain structures would stimulate equitable growth—that is, these policies would both promote innovation and ensure that the gains from innovation are broadly shared. There are a number of potential solutions at the national, state, and local levels.

Start by using the convening power of the U.S. government

The U.S. government, for example, could convene a broad range of stakeholders to create and continuously update strategic roadmaps of capabilities needed to address climate change. Recent strategies haven’t been coordinated, which has undermined our ability to lead internationally on key industries. One big case in point: The United States is still weak in battery technology. The U.S. government has done better in the past, with coordinated roadmapping, innovation, and government purchasing policies that created innovative industries in sectors ranging from agriculture to semiconductors. These policies were not perfect, denying African Americans access to policies that promoted decent incomes for family farmers, for example. But they could be easily improved upon today. The convening power could also share best practices in thinking about hidden risks and problems with lowest-unit-cost sourcing, hidden benefits of higher wages for workers and quicker reimbursement of suppliers.

The federal government could act as a high-road purchaser

Government can buy preferentially from companies that are innovative (as U.S. government purchasing jumpstarted the semiconductor industry). It can require its suppliers to pay “prevailing wages,” as is required in government-funded construction by the Davis-Bacon Act, a requirement that helps support the apprenticeships and training centers mentioned above. The Obama administration issued an executive order (which has now been overturned) blocking government purchases from companies with recent violations of labor laws. Government could also offer technical assistance to its own and others’ suppliers by expanding the Manufacturing Extension Partnership, which provides technical support for small and medium-sized manufacturers, and the Department of Energy’s Industrial Assessment Centers, which help firms redesign their operations to conserve energy.

Policymakers could nurture more productive ecosystems of firms, universities, communities, and unions

One reason for the struggles that small and medium-sized U.S. firms face is that they are “home alone,” with few institutions to help with innovation, training, and finance. For reasons of both equity and efficiency, these firms should not depend solely on their customers for strategic support. Germany’s Mittelstand (medium-sized firms) are the backbone of the German manufacturing sector due to the help they get from community banks, applied research institutes, and unions. In the United States, the unionized construction sector has developed structures that create good jobs and fast diffusion of new techniques, even though the industry remains characterized by small firms and work that is often intermittent.

Building-trades unions work with signatory employers to provide apprenticeships, continuing-education programs, and portable benefits. Other unions have begun similar efforts to create career ladders for workers in the hotel and hospital sectors. A century ago, the federal government created an innovative farming sector by funding land grant universities, which led not only to the creation of knowledge, but also created durable networks of researchers and practitioners through which such knowledge could quickly spread.

Higher wages and worker participation are key for high-road supply chains

Much research documents the ways that firms can utilize “high-road” policies or “good-jobs” strategies to tap the knowledge of all their workers to create innovative products and processes. High-road firms remain in business while paying higher wages than their competitors because their highly skilled workers help these firms achieve high rates of innovation, quality, and fast response to unexpected situations. The resulting high productivity allows these firms to pay high wages while still making profits that are acceptable to the firms’ owners.

Collaborative supply chain governance plays an important role in providing the stability needed to support these strategies, from which lead firms also benefit. To begin to restore wages and worker power, policymakers could raise minimum wages and make it easier for workers to choose a union. Knowing the need for supply chains always to be prepared to make “just-in-time” deliveries, the administration used that knowledge to make the threat of temporary shutdowns a more potent enforcement tool.

Policymakers should explore sectoral collective bargaining

Under the National Labor Relations Act, unions must negotiate with individual companies. Some have proposed amending the law to permit sectoral bargaining, in which negotiations between workers and employers cover an entire sector. This is how a number of European countries carry out collective bargaining, and it results in stronger union membership, greater worker influence over wages, conditions, and company operations, and less income inequality.

Policymakers could provide direct government services, as well as tax breaks

Simply taxing carbon isn’t sufficient to develop capabilities needed for a low-carbon economy. A coordinated approach is necessary to strengthen productive low-carbon ecosystems, simultaneously building both the demand for and the supply of assets needed for green operations such as trained workers, energy-conscious customers, capable suppliers, and producers with an understanding of energy-efficient production techniques. Similarly, simply taxing foreign producers via tariffs does not, by itself, revive supply chains that have been hollowed out over past decades.

One way of raising funds for government initiatives such as these detailed above would be to recoup the precious resources state and local governments spend seeking to attract firms to locate within their jurisdictions. Such subsidies amount to approximately $80 billion annually. A substantial portion of these expenditures goes to companies for doing something they would have done without the subsidies. Certainly, the country as a whole does not benefit when tax dollars are used to bribe private companies to locate in one U.S. location versus another. The federal government could discourage these competitions—and raise revenue—by subjecting the benefits companies receive to federal taxation. Between discouraging wasteful state and local expenditures and recouping some of the remaining expenditures, such a step could help government at all levels fund programs that genuinely support high-skill, high-wage employment.

The growth of low-road supply chains has contributed to lagging wages for U.S. workers. This decentralization of employers and processes, whether for services or products, is probably here to stay. When its purpose is to buttress quality and innovation through specialization, then this is a good thing. But policymakers at all levels of government can encourage companies, especially wise ones, with a combination of carrots and sticks, to ameliorate negative effects on innovation, profits, and, most importantly, wages, benefits, and other working conditions. These actions should be high on the list of actions taken in the next few years to strengthen the U.S. economy.