Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

- The aging of America and the provision of illness-care workers is no longer a within-family matter, posing great problems that policymakers have not done nearly enough to think about. Read Jane Waldfogel and Emma Liebman, “Paid Family Care Leave,” in which they write: “The unmet need for leave to care for a family member with a serious illness is actually more widespread and more frequent than it is for the other types of family leave. This is why its relative neglect in research and its uneven treatment by policymakers is all the more striking. For these reasons, this paper focuses on reviewing what we know and do not know about family care leave. In particular, this paper contributes to an understanding of the need for paid leave to care for a seriously ill family member and the current state of policy and research. In doing so, we draw on the best available research on family care leave where available, but because such research is often lacking, we also draw on evidence about family and medical leave more generally when necessary.”

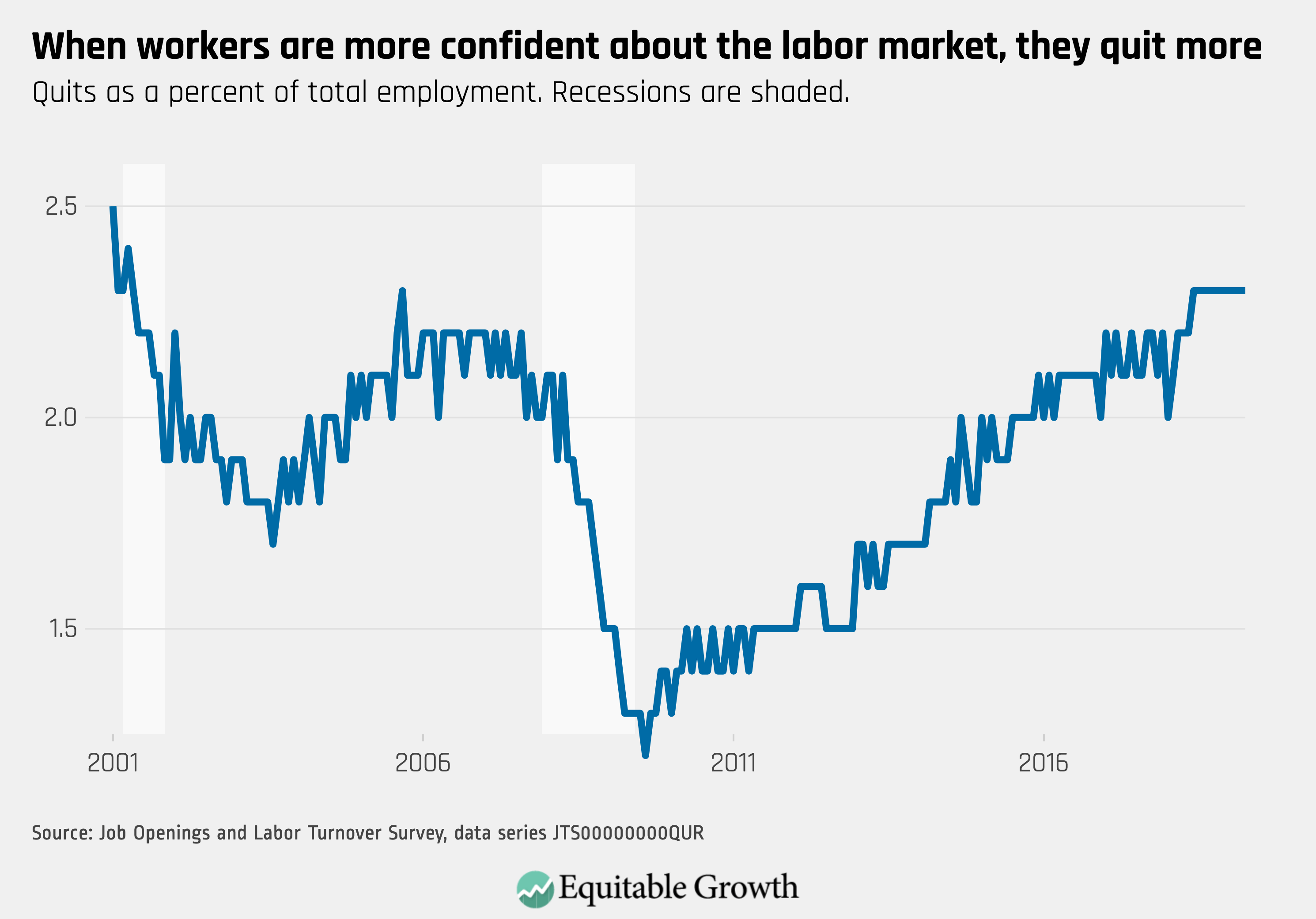

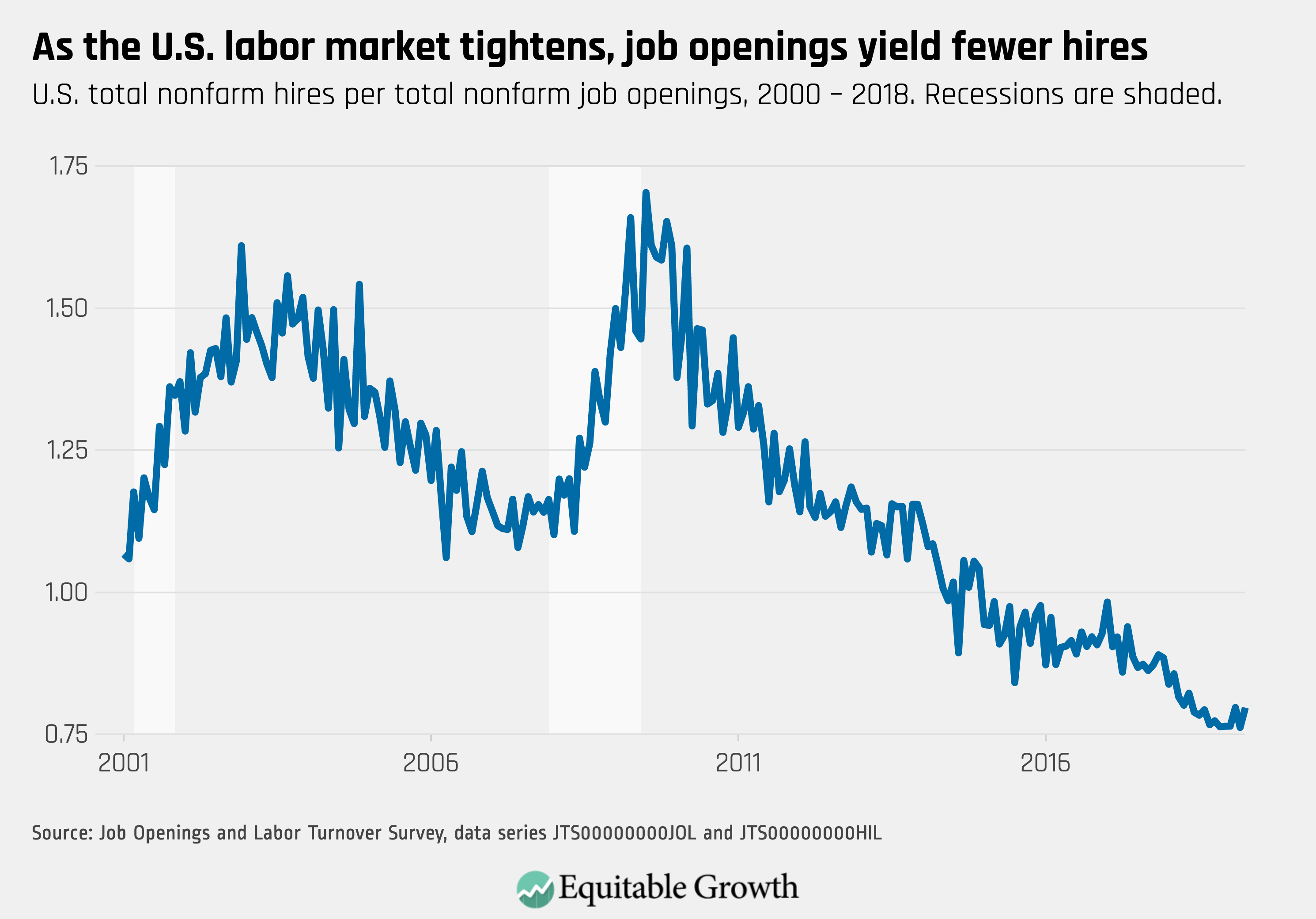

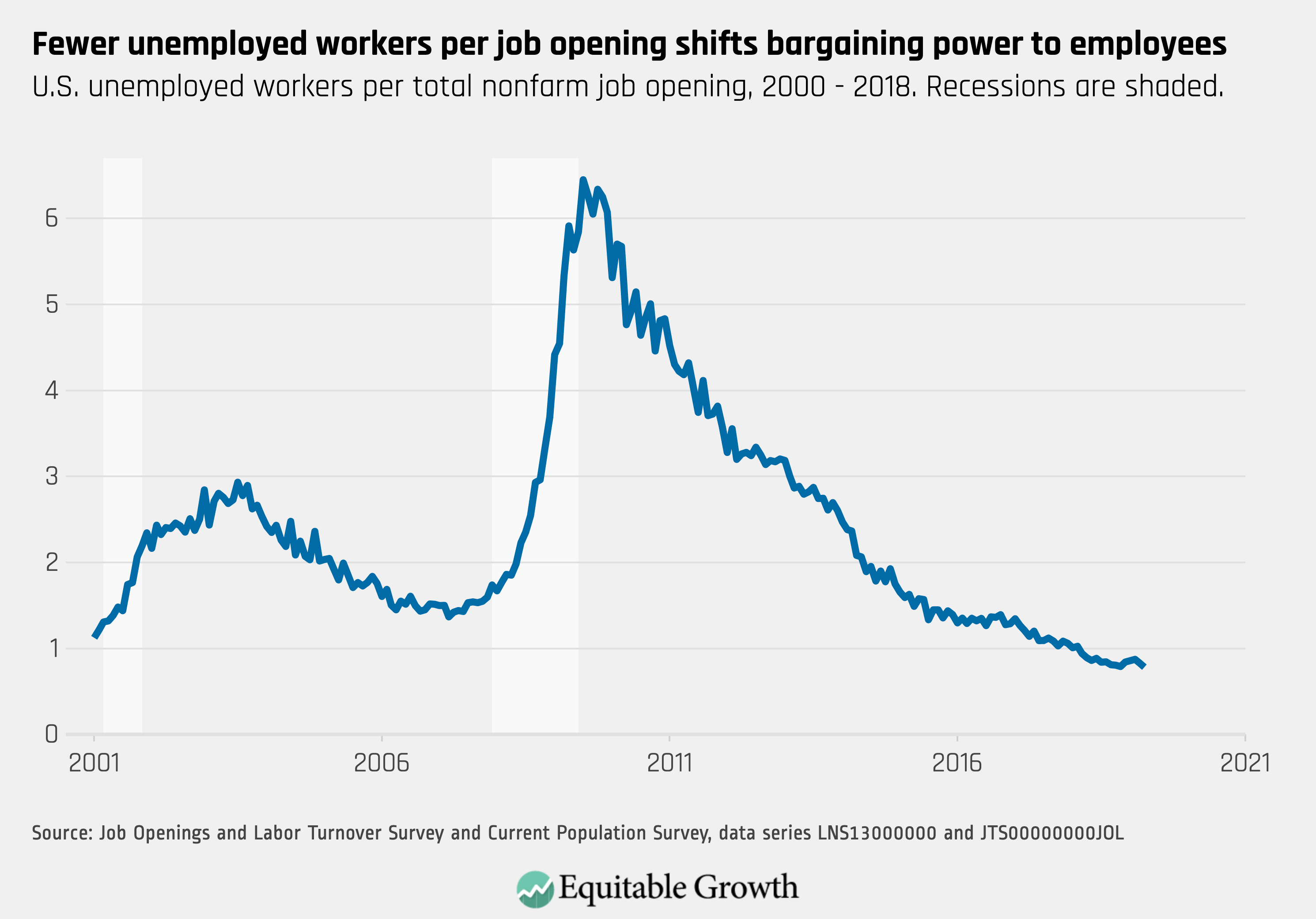

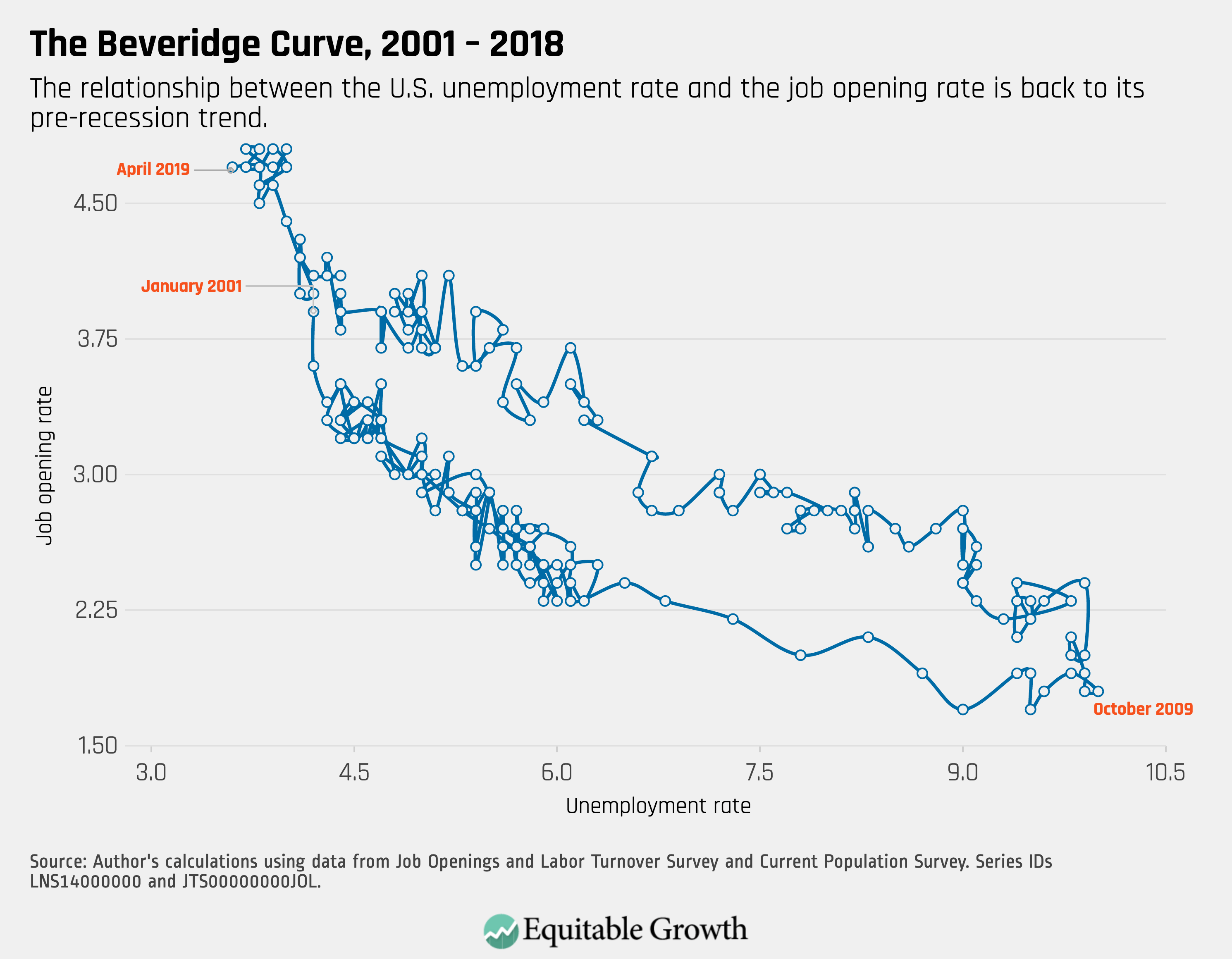

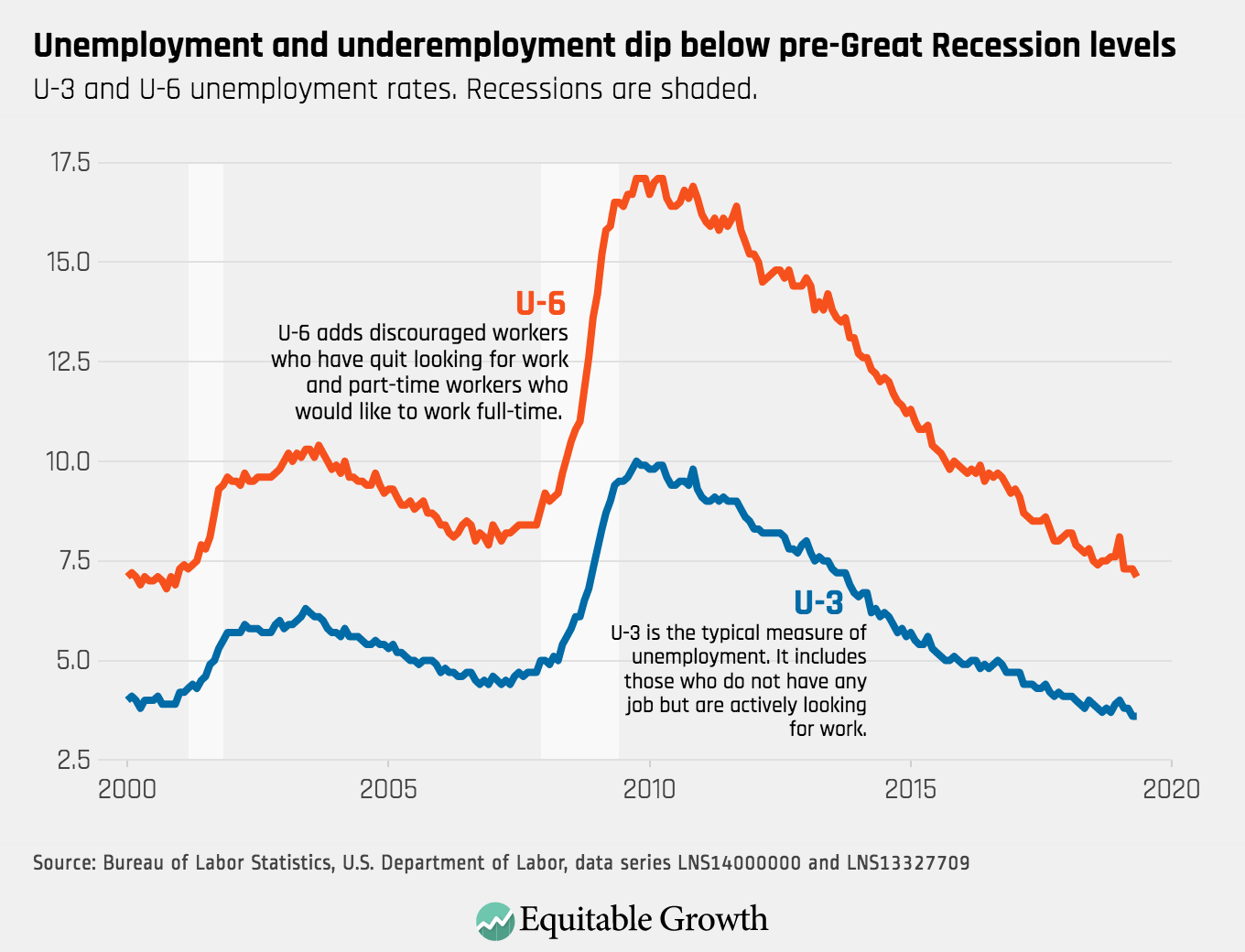

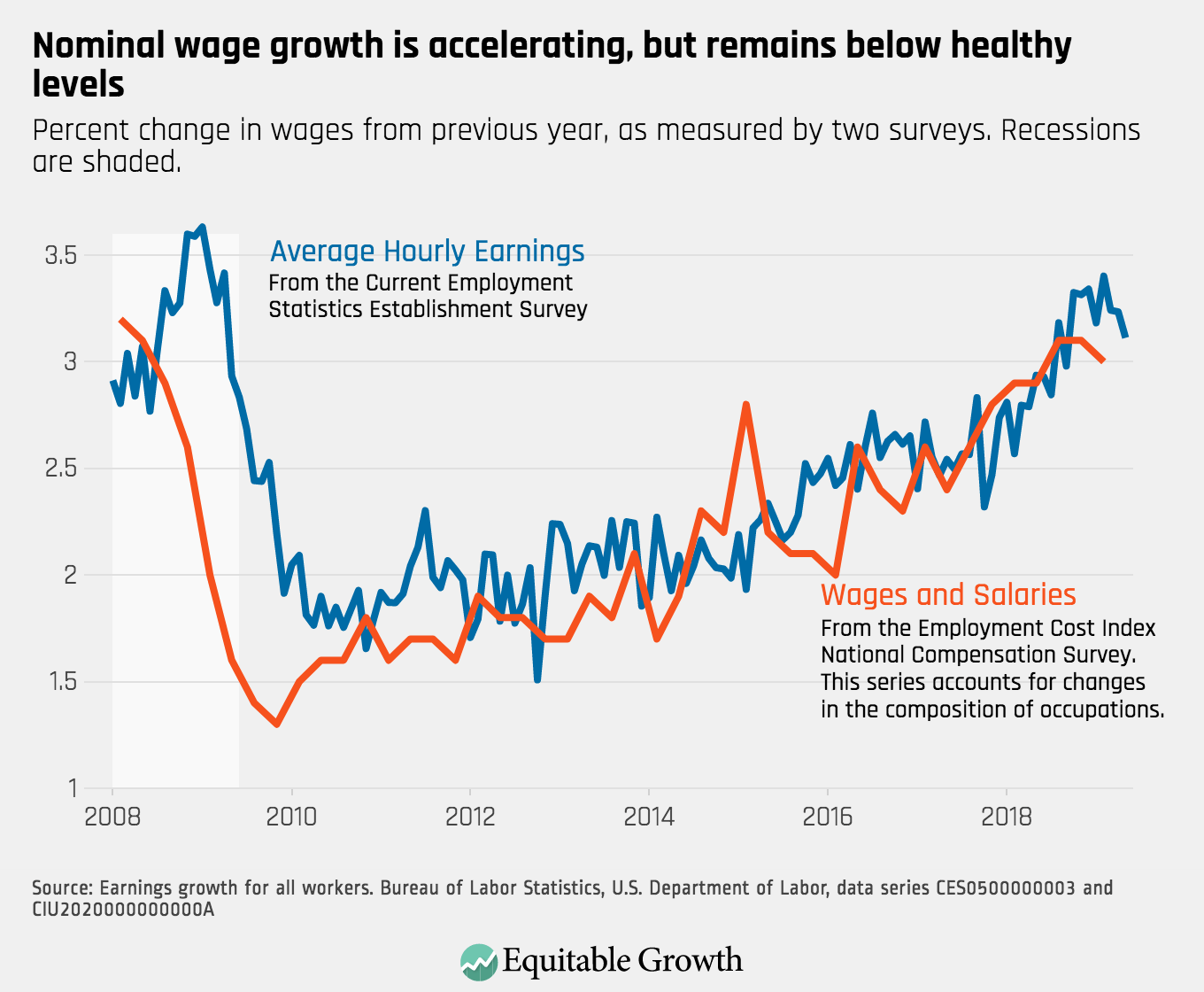

- On the eve of the 2001 recession, the ratio of unemployed workers to job openings was higher than it is now—and yet there is still next to no upward wage pressure now. This is a puzzle. Read Raksha Kopparam and Kate Bahn, “JOLTS Day Graphs: April 2019 Report Edition,” in which they write: “The ratio of unemployed workers to job openings hit a new low of 0.78, with fewer than one person looking for a job for each open position.”

- “Statement on the Passing of Our Founding Funder, Herb Sandler”: “The Washington Center for Equitable Growth … would not exist without the support and leadership of Herb and the Sandler Foundation … He was generous with the resources of the Sandler Foundation and equally demanding when it came to creating, developing, and implementing their mutual vision of a nonprofit grantmaking organization that would fund original academic research and convey the evidence and policy ideas that emerged … The sadness felt by all of us at Equitable Growth is leavened by the knowledge that Herb lived to see the organization walk and then break into a run.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- I confess I do not understand what is to be done here—these internet platforms are not utilities (the technology is not stable and investments are not large enough), so rate regulation would seem inappropriate. The economies of scale on the production side and the economies of scope on the consumption side are very large, so it would seem inappropriate to sacrifice them to generate competition at the core services of each platform. Consumer surplus appears to be very large, so reducing the profits to successful innovators seems a very bad idea. And there is the question of whether these firms are giving their customers what they need instead of what they think they want—but do recall that, in early generations, one socialist critique of the market was that the market economy was making people unfree by failing to force them to wear identical blue overalls, drive identical utilitarian black cars, and listen to properly uplifting music: Read Ben Thompson, “Tech and Antitrust,” in which he writes: “That is not to say that tech deserves no regulation: questions of privacy, for example, are something else entirely. Nor, for that matter, is antitrust irrelevant in the United States generally: concentration has increased dramatically throughout the economy. What is driving that concentration matters, though: at the end of the day tech companies are powerful because consumers like them, not because they are the only option. Consumer welfare still matters, both in a court of law and in the court of public opinion.”

- The bond market thinks a recession is likely. The National Bureau of Economic Research—if it still paid attention to anything but payroll—would now be wondering when it should call the peak. But we seem to have decided that a recession is not a recession of economic activity in general from a previous peak, but rather a sudden, sharp, significant, and asymmetric fall in employment. The key would then be found in the hearts and minds of businesses: Are things likely to be bad enough in the future that we need to start shedding labor now? Can we use the excuse of ‘hard times’ to break our implicit contracts with our workers without incurring heavy costs in terms of reduced worker morale? When the answers two those two questions become ‘yes,’ that is a recession. We are not yet there—and we have no good models of what would push us there. Read Menzie Chinn, “Recession Anxieties, June 2019,” in which he writes: “Different forward-looking models show increasing likelihood of a recession. Most recent readings of key series highlighted by the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee [or BCDC] suggest a peak, although the critical indicator—nonfarm payroll employment—continues to rise, albeit slowly.”

- A reminder that eliminating trade barriers and boosting trade through reducing tariffs, reducing quotas, and harmonizing regulations is one of the two things (along with deficit reduction at full employment when interest rates are high) we know how to do to materially and significantly boost prosperity in the medium run. Yes, it has an impact on income distribution. But everything has an impact on income distribution. Focusing your policies for equity on trade restrictions is counterproductive. Read Doug Irwin, “Does Trade Reform Promote Economic Growth? A Review of Recent Evidence,” in which he writes: “There appears to be a measurable economic payoff from more liberal trade policies … about 10–20 percent higher income after a decade … The gains in industry productivity from reducing tariffs on imported intermediate goods … show up time and again in country after country … As Estevadeordal and Taylor (2013, 1689) ask, ‘Is there any other single policy prescription of the past 20 years that can be argued to have contributed between 15 percent and 20 percent to developing country income?’”

- I am not sure whether what is needed is for economics to “go digital” as for economics to finally recognize what John Maynard Keynes called “the end of laissez-faire.” But since he wrote about the end of laissez-faire 94 years ago, I am not holding my breath for a better economics. Read Diane Coyle, “Why Economics Must Go Digital,” in which she writes: “Drug discovery is an information industry, and information is a nonrival public good which the private sector, not surprisingly, is under-supplying … Yet the idea of nationalizing part of the pharmaceutical industry is outlandish from the perspective of the prevailing economic-policy paradigm … Should data collection by digital firms be further regulated? … The standard economic framework of individual choices made independently of one another, with no externalities, and monetary exchange for the transfer of private property, offers no help.”