A new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research compares intergenerational mobility within and between the United States and Canada to yield new insights into the impact of public policy, race, and inequality in influencing children’s economic outcomes. The paper, by Université du Québec à Montréal economists Marie Connolly and Catherine Haeck and City University of New York economist Miles Corak recreates for Canada Harvard University economist Raj Chetty’s analysis of how intergenerational mobility varies dramatically by geography in the United States, allowing for a better understanding of how intergenerational mobility varies both within and between the two countries.

The paper, released last month, finds that while mobility also varies greatly by geography within Canada, overall a parent’s income north of the border is less strongly related to a child’s adult income than in the United States. This finding echoes previous research showing that intergenerational mobility is lower in the United States than in other developed economies.

In the United States, privilege and disadvantage persist more than they do in Canada. The three authors find, for example, that “a child raised by top percentile parents in the United States will rank about 31 to 34 percentiles higher in the income distribution than a bottom percentile child, but in Canada this difference, at 21 to 23 percentiles, [is] a full decile lower.” At the bottom end of the distribution, while a Canadian child raised by parents in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution will likely grow up to have an income that puts her around the 40th percentile of the income distribution, an American child would have to start out at the 30th percentile to achieve the same adult economic outcome.

This “stickiness at the ends” of U.S. mobility has been observed by other researchers previously, and the steeper climb to ascend the income ladder in the United States means that, “The U.S. ‘middle class’ is within easier reach for lower income Canadian children, than it is for low income Americans,” the authors write.

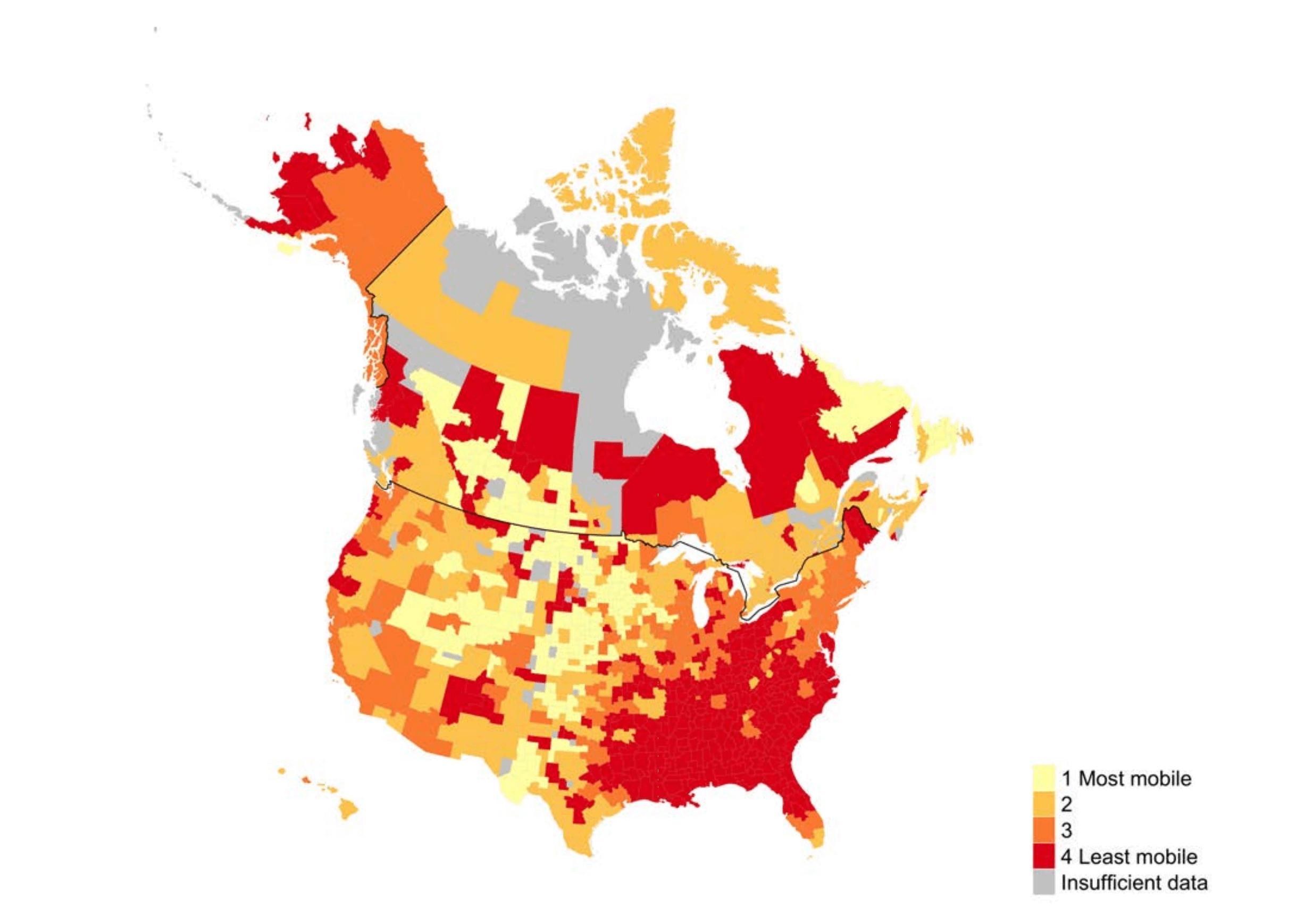

Overall mobility outcomes are better for Canadian children than American, but there are parts of Canada where mobility is just as low as the parts of the United States where mobility is extremely low, namely the American South. The parts of Canada with extremely low mobility are northern provinces that have large First Nation indigenous populations, but also are a small part of Canada’s overall population. In contrast, in the United States, the areas of low mobility account for a large bulk of the country’s population. “Most Americans live in regions of less mobility, with parental income ranks being more strongly related to child ranks, and the chances of escaping low income being lower,” Connolly and her co-authors note.

They also point out that these findings underscore the role of race in U.S. mobility outcomes: “To the extent that the communities we highlight as part of … the low mobility cluster dominated by the southern American states, have a higher black population, then this must be part of the explanation for the cross-country differences.” This point echoes findings by Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago economist Bhash Mazumder and Harvard economist Raj Chetty—that mobility for black Americans is far lower than that for white Americans—the latter of whom found this to be true for black men even after controlling for parents’ income, wealth, education, and neighborhood.

The interaction between race and public policy in explaining Americans’ lower mobility outcomes can also be seen in areas of the second-lowest mobility outcomes, which the authors refer to as Cluster 3 and are found almost exclusively on the U.S. side of the border. In offering an explanation for why Cluster 3 is an almost exclusively U.S. phenomenon, the authors highlight research by Ellora Derenoncourt—a postdoctoral research associate in economics at Princeton University and an Equitable Growth grantee—which found that northern cities where black Americans moved to from the South during the Great Migration of the mid-20th century changed in ways that hurt upward mobility for blacks. For example, enrollment of white children in private schools increased and public spending on policing increased. “Her results suggest that access to public goods and schooling became more restrictive, [with] ‘white flight’ depriving these migrants and their children of public investments that in turn had long-term negative consequences that continued across generations,” Connolly and her co-authors say of Derenoncourt’s research.

If this is the case, they write, then the areas of low mobility found in the United States in the Deep South and Industrial North represent the interrelated intermediating role race and public policy responses play in mobility outcomes in the United States. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

U.S. and Canadian rates of economic mobility

A cluster map of mobility rates shows that while there are areas of low mobility in both Canada and the United States, areas of low mobility are more widespread in the United States

Source: Marie Connolly, Miles Corak, and Catherine Haeck, “Intergenerational Mobility between and within Canada and the United States.” Working Paper No. 25735 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019), available at LINK.

Connolly, Corak, and Haeck argue that their comparison of intergenerational mobility within and between Canada and the United States is particularly apt because of similarities between the two countries—namely, their physical size, their heterogenous populations, and very similar conceptualizations of what the “American” or “Canadian” Dream is. “Sixty percent of American respondents ranked being able to succeed regardless of family background eight or higher on a ten point scale, while 59 percent of Canadians did so,” they note. Despite the many similarities between the two countries, the differences in children’s outcomes between the two illustrate the role that race and public policy play in influencing children’s economic outcomes.