When the U.S. economy is cruising down the road in high gear, as it is these days, it can be hard to focus on the next engine failure. Having occurred seven times in the past 50 years, recessions—like death and taxes—are inevitable. And they are painful, with harsh short-term effects on families and businesses and potentially deep long-term ill effects on the economy and society. But policymakers can ameliorate some of the next recession’s worst effects and minimize its long-term costs if they adopt smart policies now that will be triggered when the first warning signs of the downturn appear.

What are the best policies to put in place today? Policymakers need a guide, and Equitable Growth has joined forces with The Hamilton Project to advance a set of specific, evidence-based policy ideas for shortening and easing the impacts of the next recession. In a new book, Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy, experts from academia and the policy community propose six big ideas, including two entirely new initiatives and four significant improvements to existing programs, all to be triggered when the economy shows clear, proven signs of heading into a recession.

Recession Ready was edited by Equitable Growth Executive Director Heather Boushey, Ryan Nunn, a fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution and policy director for The Hamilton Project, and Jay Shambaugh, director of The Hamilton Project, senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, and professor of economics and international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University.

Automatic stabilizers for the economy are anything but a new concept. When a recession hits, the tax system and a number of key programs, from Unemployment Insurance to Medicaid, already cushion its effects by giving families suffering from unemployment or underemployment greater resources to cushion the blow or, in the case of the tax system, taking less (or nothing) in taxes. These results are important not only for families but also for the overall economy, which desperately needs the injection of greater resources. But as we have seen in most recessions, the existing automatic stabilizers are not nearly enough.

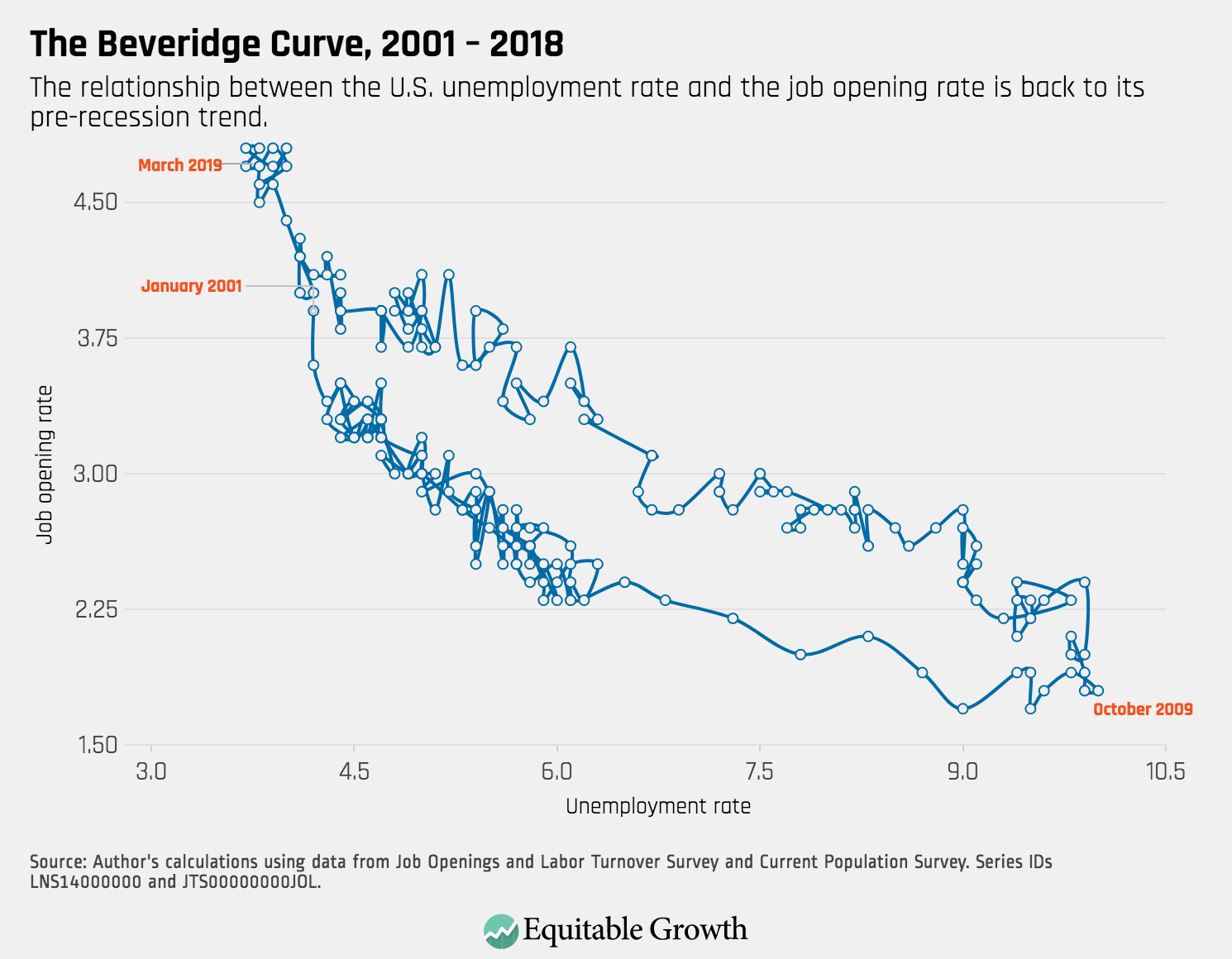

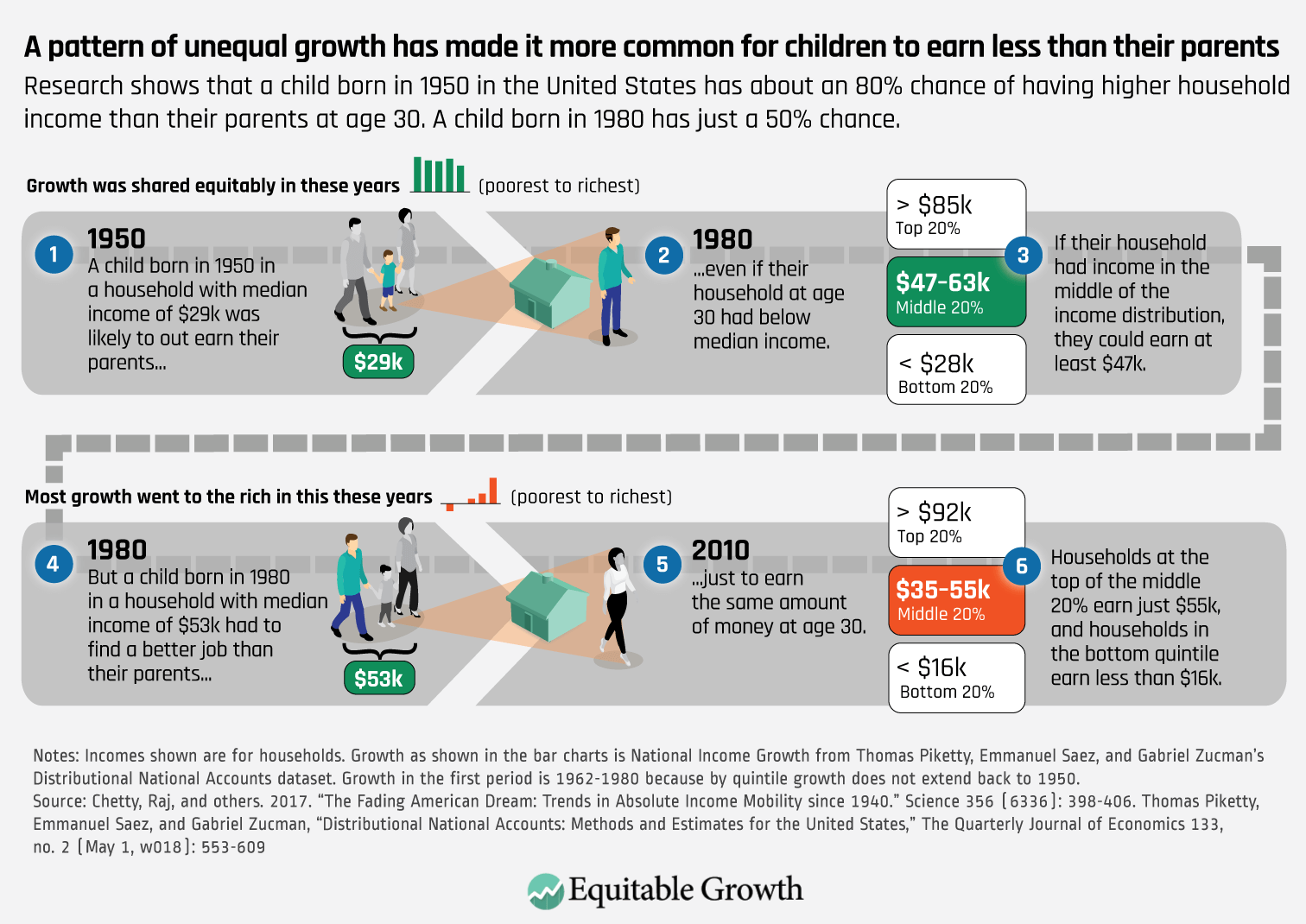

Recessions have victims. Millions of workers can lose their jobs. A generation of young people seeking to enter the workforce may find it daunting or even impossible. Families must contend with depleted savings and making painful choices among life’s necessities. And thriving businesses, especially small businesses, can be brought to their knees, hurting employers and employees. What’s worse, the most vulnerable are disproportionately affected. Numbers from the most recent downturn, while a severe example—it’s called the Great Recession for a reason—give an idea of the potential damage. The unemployment rate doubled to 10 percent and took 7 years to get back to its pre-recession level, 8.7 million jobs disappeared, and more than 5 million additional people were thrown into poverty—a number that would have been far greater in the absence of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. There is evidence that these losses will have a long-term impact on careers and earnings, especially for those who entered the job market during the recession.

The new Hamilton Project-Equitable Growth book provides background on past recessions, establishes the need for action ahead of the next recession, and contains a chapter on each of the six concrete ideas. The four proposals for strengthening existing programs are:

- When workers lose their jobs, the Unemployment Insurance system is a first line of defense for them and their families. It is also a critical automatic stabilizer in recessions, because spending ramps up substantially as unemployment mounts. Fewer workers, however, use the system than one might expect, and some are excluded by the program’s rules. The Extended Benefits program, which kicks in during periods of high unemployment, has not been effective in providing economic stimulus. Gabriel Chodorow-Reich of Harvard University and Equitable Growth grantee John Coglianese, now of the Federal Reserve Board, propose to expand eligibility for Unemployment Insurance and encourage take-up of its regular benefits. They also propose to strengthen the Extended Benefits program by several means, including making it fully federally financed.

- It falls on the federal government to counter recessions, as most states are prevented from doing so by balanced-budget requirements. Indeed, these requirements sometimes force states to reduce benefits and cut spending generally in the wake of lost revenues. Healthcare is the largest single category of state funding and therefore critical to state governments’ response to a recession. A proposal by Matthew Fiedler of the Brookings Institution, Equitable Growth Steering Committee Member Jason Furman, and Wilson Powell III of Harvard University aims to reduce state budget shortfalls during recessions by about two-thirds and avoid state budget cuts during these periods by increasing the federal matching rate for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program during economic downturns.

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is the largest program in the nation’s hunger safety net, reducing hunger and malnutrition for families and improving health, especially for infants and children. Because its benefits are spent quickly, it also boosts the economy, especially during a downturn. Yet current work requirements limit the program’s ability to help stabilize the economy during a recession, as finding work is an even greater challenge during economic downturns. Hilary Hoynes of the University of California, Berkeley and Equitable Growth grantee Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University propose to limit or eliminate work requirements for supplemental nutrition assistance during recessions or permanently and to automatically increase benefits by 15 percent during recessions.

- The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program is a source of cash support for low-income families with children. It is a core part of the nation’s economic security system. But because the federal contribution is a fixed block grant to the states, it reaches only a small share of very disadvantaged families with children, and it does not serve as a stabilizer during economic downturns. Indivar Dutta-Gupta of the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality proposes a countercyclical stabilization program through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program that would expand federal support for basic assistance during recessions and create a new, ongoing program to support state job subsidy efforts and provide a larger federal match of that state spending during economic downturns.

The two new automatic economic stabilizer programs in the Hamilton Project-Equitable Growth book are for infrastructure and direct payments to individuals:

- Infrastructure spending provides a fundamental underpinning for economic growth, supporting good-paying jobs during its expenditure and contributing to economic activity with long-lived capital goods—new roads, bridges, and buildings. But new projects can be slow to get off the ground during a recession, reducing their potential cumulative impact as an economic stabilizer. Andrew Haughwout of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York proposes an automatic infrastructure investment program. The federal government would help states develop and maintain a catalogue of potential infrastructure projects, with the work on projects triggered at signs of a coming recession. Under the proposal, funding for the Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development, or BUILD, program, run by the U.S. Department of Transportation, would automatically be expanded in a recession to get top projects underway relatively quickly.

- Research shows that significant, direct lump-sum stimulus payments to individuals in response to a recession are effective at boosting consumer spending quickly. Payments that are smaller or more spread out are not as effective. Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board Member Claudia Sahm of the Federal Reserve Board proposes to boost consumer spending during recessions by creating a system of direct stimulus payments to individuals that would be automatically triggered when rising unemployment signaled a coming recession. Additional annual payments would be triggered if the recession continued beyond the first year.

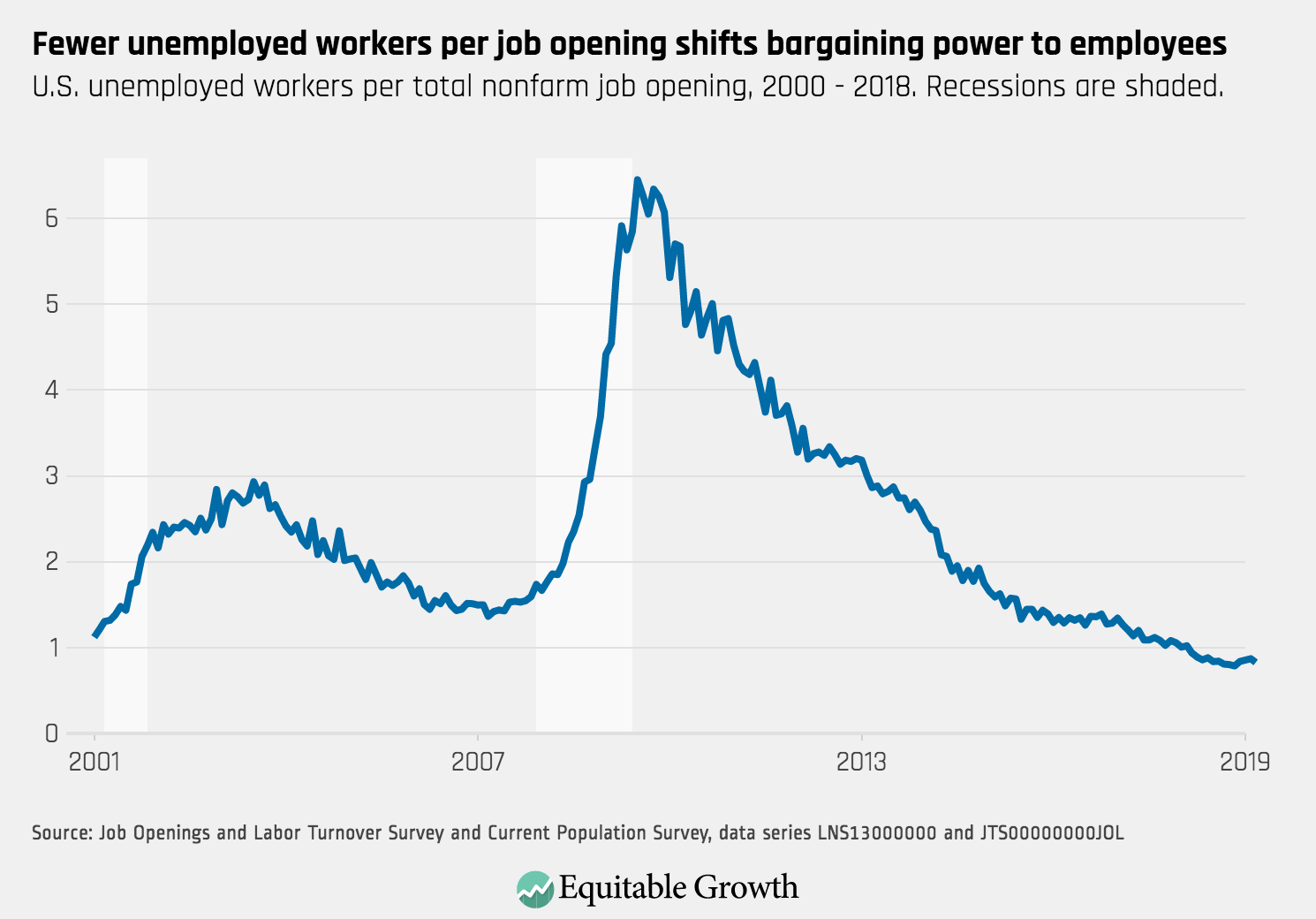

For the most part, these initiatives are countercyclical. As pointed out by the editors and Jimmy O’Donnell of The Hamilton Project in an early chapter, unemployment rates have reliably signaled the beginnings of recessions. These programs are to be triggered automatically by proven signs of a recession and expire when the economy is recovering. They inject funds into the economy to combat recession, and they withdraw those funds to avoid excessive stimulus during a recovery. Their activation would not prevent Congress and the administration from taking other measures to stabilize the economy during recessions and their aftermaths. But they would ensure significant, timely government action beyond the inadequate automatic spending that occurs under existing law. Because they affect different populations and have different implementation speeds, they are designed to be considered as a package in order to stimulate demand from individuals and families at all income levels and have a sustained impact. Congress should consider them now, because when the next recession appears on the horizon, it may be too late.