Reconsidering progress this Juneteenth: Eight graphics that underscore the economic racial inequality Black Americans face in the United States

While Juneteenth marks a day of resilience, endurance, and emancipation for Black Americans, this year’s anniversary is also a harsh reminder of the delayed freedom granted in 1865. For many, there is a renewed interest in the day traditionally meant to celebrate freedom, as the country grapples with two viruses eating away at the nation—COVID-19 and White supremacy—both of which underscore the nation’s longstanding history of institutional racism and racial inequality.

This year’s 155th anniversary comes at a time marked by global unrest and protests against systemic racism and police brutality that led to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, and countless other Black Americans. This same level of disparate impact can be seen in national coronavirus data, which show Black Americans losing their jobs and dying at nearly three times the rate of White Americans.

The economic disparities between Black and White Americans are prolonged and profound. In observance of Juneteenth, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth is reflecting on the perceived progress made in the lives of Black Americans and highlighting evidenced-backed policy solutions needed to reduce economic racial inequality.

Eight graphics on wages, wealth, and health

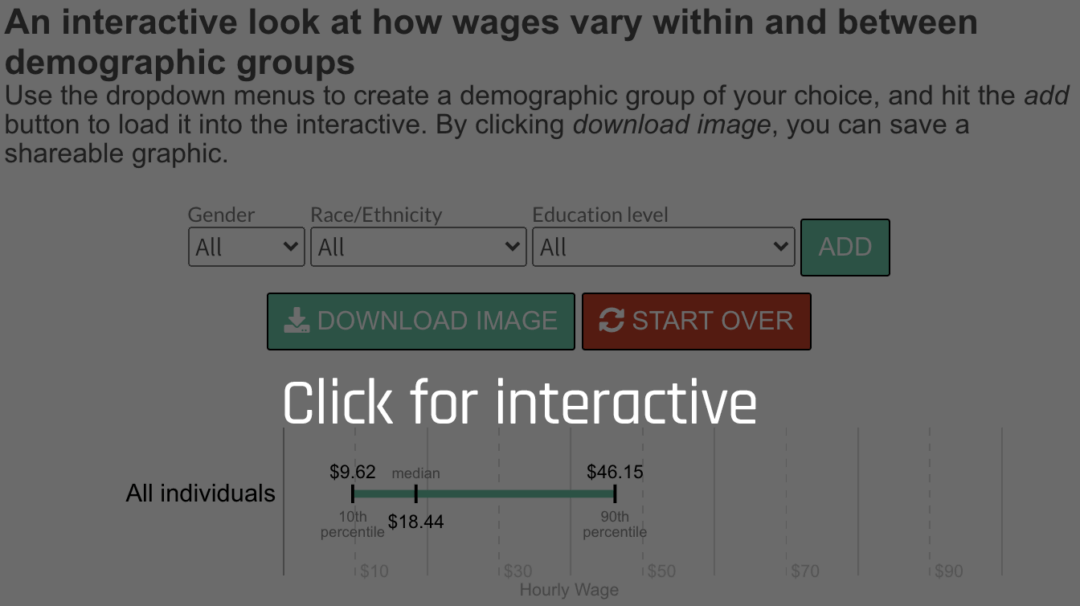

Black workers, especially Black female workers, have lower salaries than White workers with similar levels of education. While the median White male worker with a college degree earns $31.25 an hour, the median Black male worker with a college degree only earns only $23.08. This is only $5 more than a White male worker with a high school degree. Some of this wage gap is due to occupational segregation, but the majority of it is “unexplained” and is attributed to discrimination. (See Interactive.)

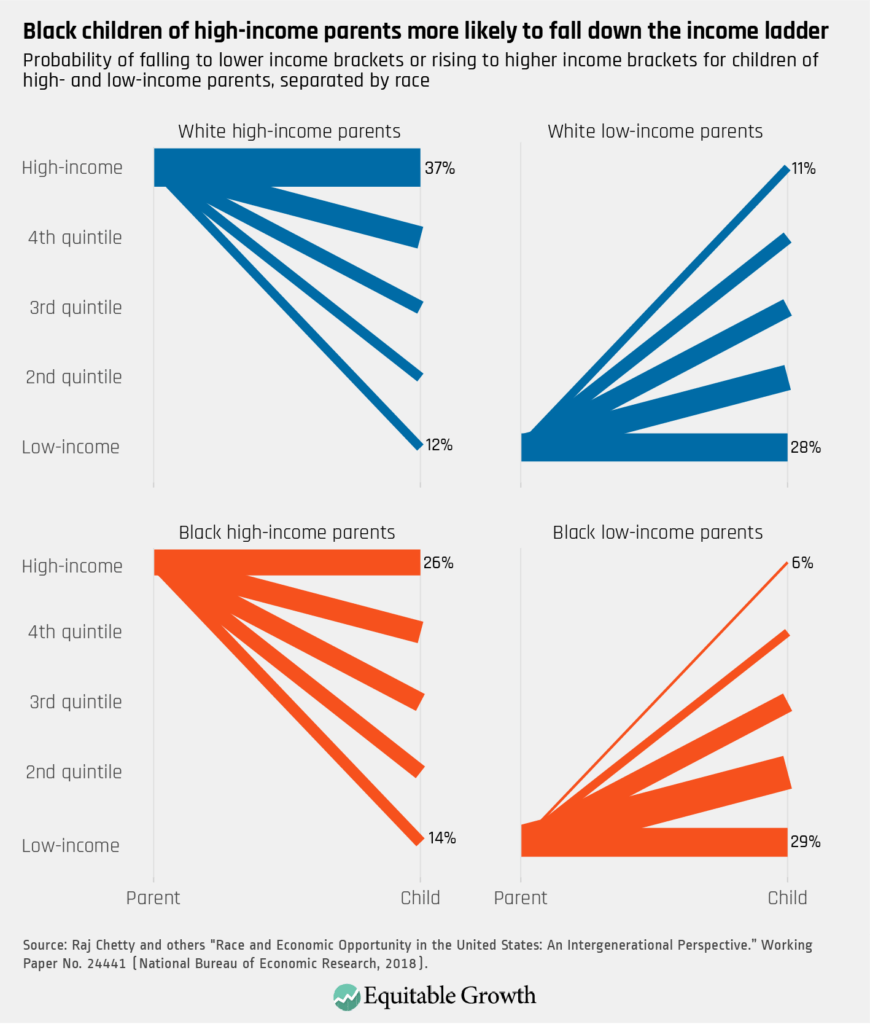

Black Americans also experience a disparity in intergenerational mobility, or the relationship between their income as an adult and their parents’ income at a similar age. While Latinx and Asian Americans have intergenerational mobility rates converging with those of White Americans, Black and Native Americans do not. One reason for this is that even when raised in high-income families, Black children are far more likely to experience downward mobility. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The role of the U.S. criminal justice system in driving downward mobility for Black Americans is strongly hinted at in this research. More research is clearly needed to further our understanding of the economic consequences of our racist criminal justice system.

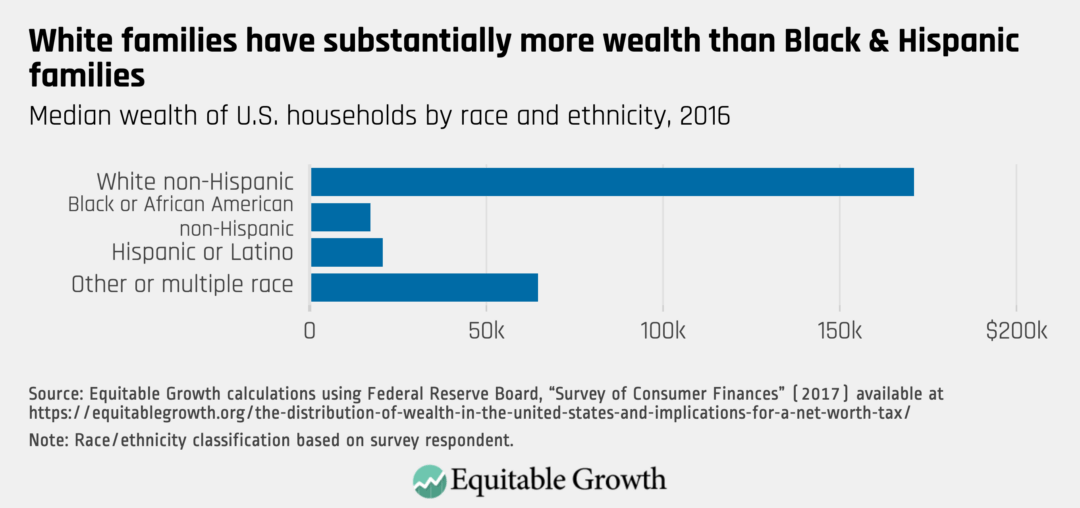

The Black-White racial wealth divide is even larger than the Black-White income gap. White families have median wealth of $171,000 while Black families have median wealth of only $17,600. Differences in income or education cannot explain this wealth divide between White and Black American families—the net worth of Black families in the top income quintile is only $262,800, which is barely more than half that of White families in the top income quintile. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

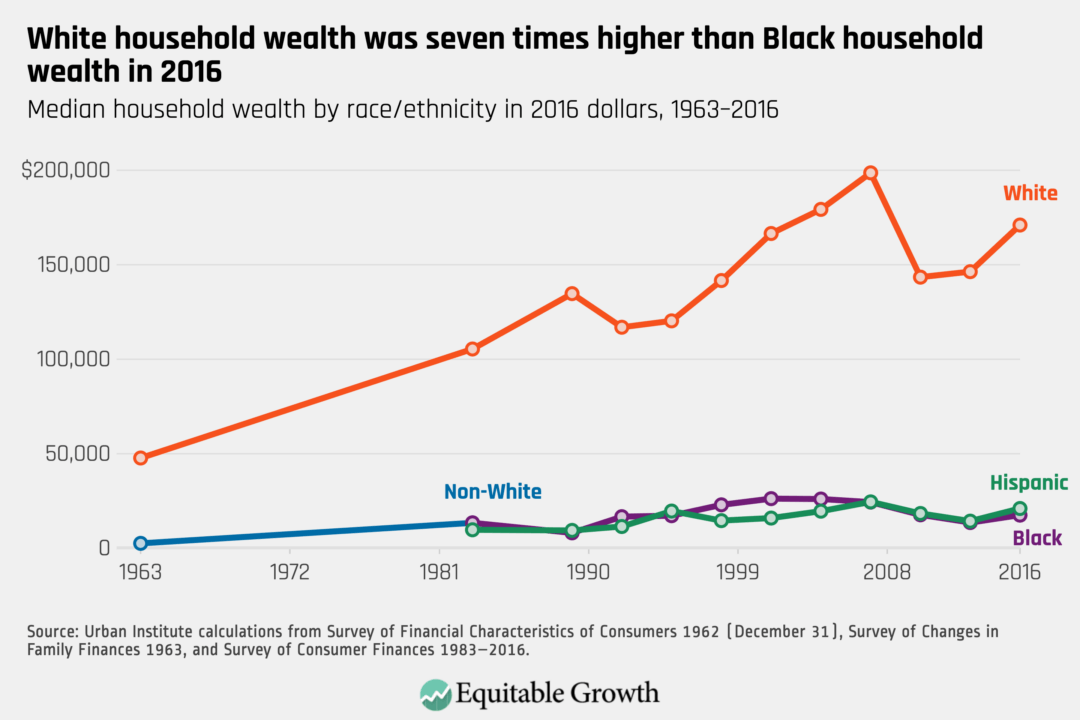

The Black-White racial wealth divide has not decreased over time, despite Black Americans’ education and income levels improving over time. This again belies arguments that the economic racial inequality that Black Americans experience is due to differences in skills rewarded by the marketplace. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

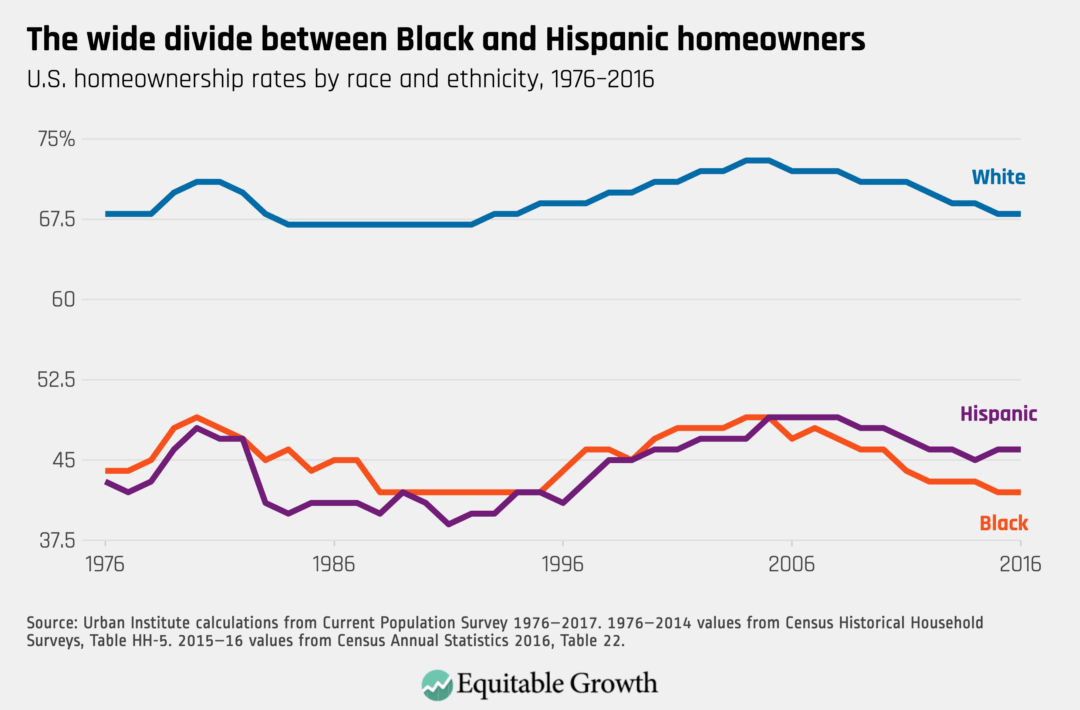

One major contributor to the Black-White racial wealth divide is the systemic policy support for White homeownership and systematic barring of Black homeownership through federal policies that created redlining and the modern mortgage market in the 1930s. These policies have had lingering effects for decades, and despite the Fair Housing Act of 1968 legally barring discrimination in housing, Black homeownership rates have not meaningfully changed. They were further worsened during the mid-2000s housing bubble, when banks gave Black borrowers subprime mortgages even when they had better credit scores than White borrowers. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

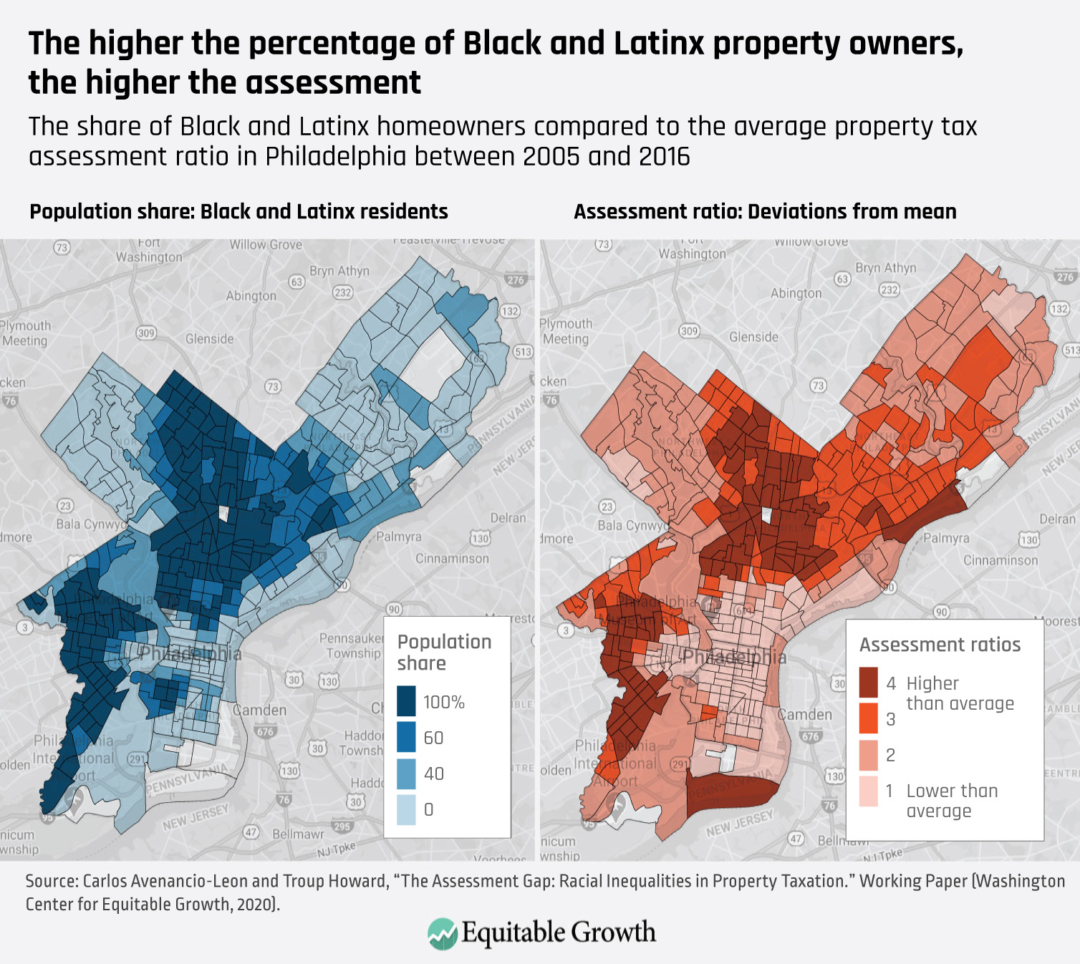

In addition, even when able to purchase homes, Black and Latinx homeowners face higher property tax burdens. New research from Carlos Avenancio-León of Indiana University Bloomington and Troup Howard of the University of California, Berkeley found that even within regions where every homeowner theoretically faces the same rate of taxation, Black and Latinx homeowners nonetheless end up paying a 10 percent to 13 percent higher tax rate, on average, within the same local property tax jurisdiction. (See Map.)

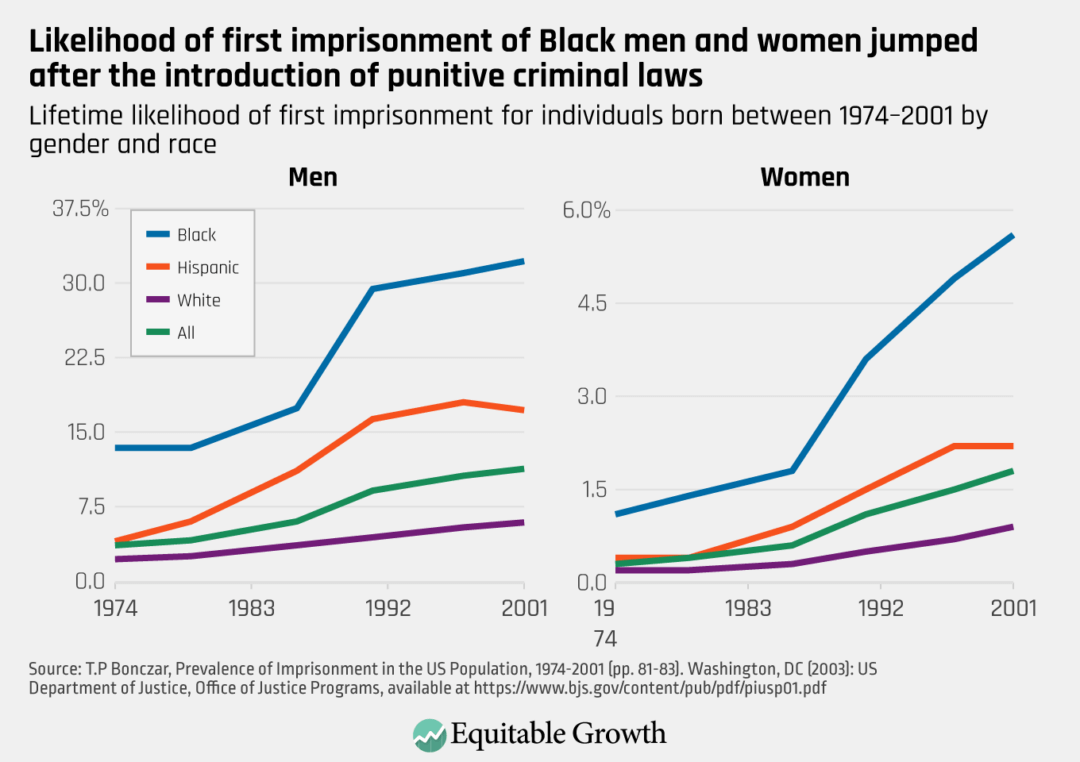

An issue in its own right, the disproportionate incarceration of Black people is also a contributing factor to economic racial inequality. Time served is time away from the labor market, detrimental to finding and keeping future employment, and penalizes even those found innocent through administrative fines and fees. The dramatic increase in incarceration over recent decades has not been driven by increases in crime but rather by a shift to more punitive sentencing regimes that disproportionately fall on Black and Latinx communities. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

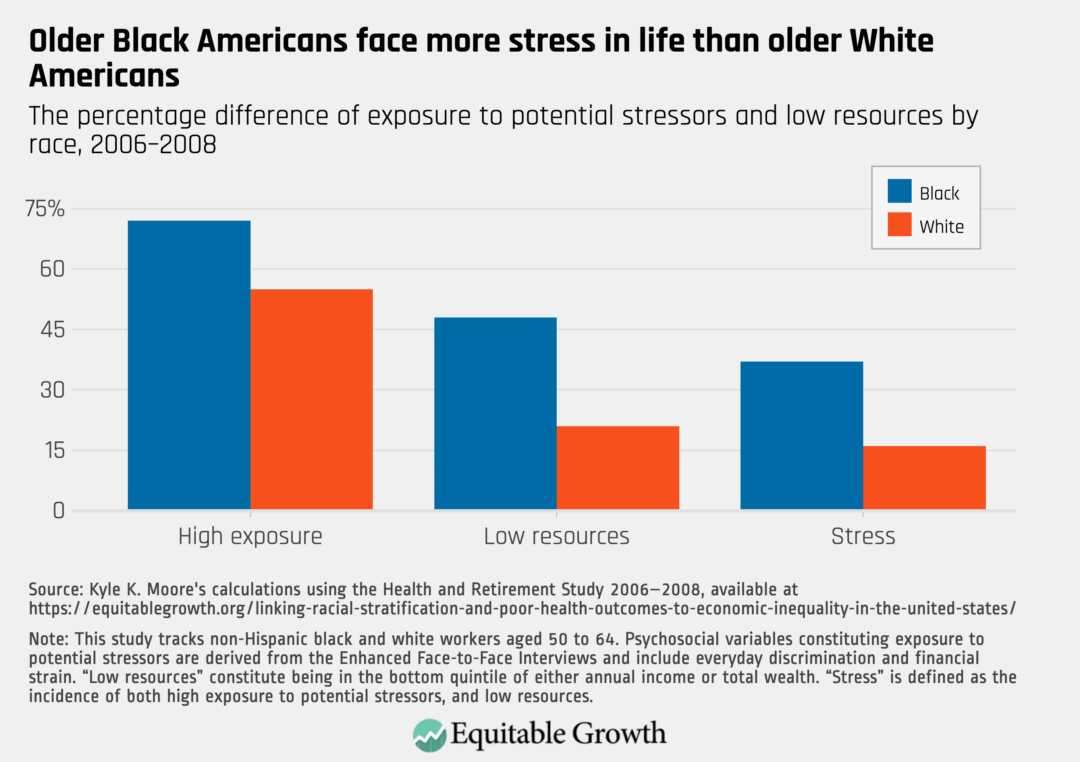

The health disparities that Black Americans experience in conditions such as hypertension and inflammation are an example of the limits of an economic framework for understanding racial disparities. Even at similar levels of income and education, Black Americans experience worse health outcomes. One reason is the discrimination and racism experienced daily by Black Americans, which exacts a physical toll that increases the incidence of these types of conditions. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Higher incidence of these types of conditions is already a matter of public health justice. But when paired with the novel coronavirus that turns these pre-existing conditions into acute vulnerabilities, it becomes especially so. Layer on top of this the disproportionate representation of Black workers in jobs where they’re exposed to the coronavirus, the housing they’re constrained to because of the ongoing legacy of redlining and other discriminatory mortgage lending practices, and other structural inequalities, and there now is a perfect storm for a global health pandemic to vastly disproportionately impact Black communities.

Policy solutions

The economic racial inequality facing Black Americans has not improved over time despite rising education levels and a growing national economy. That is because economic racial inequality is due to intentional public policies of discrimination, segregation, and incarceration. Therefore, only structural economic change will be sufficient to address economic racial inequality.

“There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair.”

Martin Luther King Jr.

One group of policy solutions to consider focus on wealth building. Policies that simply ensure workers are being paid fairly and equitably the money they earn is an easy place to start. Possible suggestions include sufficiently funding the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission so it can enforce existing anti-discrimination labor laws and prosecute wage theft, and eliminating the tipped minimum wage, which is racist in origin and was supported along starkly racial lines here in Washington, D.C.

Policies that address the racist differences in credit options—such as postal banking, as recommended by Washington Center for Equitable Growth board member and UC Irvine law professor Mehrsa Baradaran—and reforms to the Community Reinvestment Act are another group. Addressing student debt, which disproportionately burdens Black students as a consequence of the Black-White wealth divide, will also be necessary, either through a progressive approach or even outright cancellation. But, ultimately, centuries of enslavement, institutionalized violence, purposeful exclusion from the White wealth-building policies of the New Deal, and ongoing labor market discrimination—all of which have contributed to the Black-White wealth gap—call for a reparations program on a scale sufficient to address the problem.

Another group of policy solutions focused on addressing the racism of the U.S. criminal justice system would also serve to redirect taxpayer dollars toward public investments that improve economic growth and mobility for Black Americans. Defunding the police would redirect public funds from policing to education, social services, and other pro-social public goods that will boost intergenerational mobility. This would merely reverse the policy choices many cities made decades ago, as Black migrants from the South moved to northern cities as part of the Great Migration, with those cities responding by decreasing public expenditures—except on policing.

We need to enact policies that begin to eradicate economic racial inequality as soon as possible. While our nation made some progress toward making the U.S. economy and society much more equitable since enslaved Black Americans gained their freedom in 1865, the legacy of Jim Crow and the continuing economic racial discrimination so evident in the graphics above shows how much further we have to go. Downward mobility is on the rise, racist policies have not been eradicated, and the racial wealth divide is not only not closing but rather is increasing. It is abundantly clear that we still have much work to do.

A few suggestions on individual scholars to follow for in-depth reading on these issues:

Olubenga Ajilore, senior economist, Center for American Progress

Algernon Austin, senior researcher, NAACP Legal Defense Fund

Carlos Avenancio, assistant professor of finance, Indiana University Bloomington

Nina Banks, associate professor of economics, Bucknell University

Mehrsa Baradaran, professor of law, University of California, Irvine School of Law

Peter Blair, assistant professor of education, Harvard Graduate School of Education

Lisa Cook, professor, Michigan State University

Robynn Cox, assistant professor of social work, University of Southern California

William Darity, Jr., Samuel DuBois Cook professor of public policy, African and African American studies, and economics, and the director of the Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University

Ellora Derenoncourt, incoming assistant professor, University of California, Berkeley

Dania Francis, assistant professor of economics, University of Massachusetts, Boston

Darrick Hamilton, executive director of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, Ohio State University

Bradley Hardy, associate professor, American University

Kilolo Kijakazi, institute fellow, Urban Institute

Trevon Logan, Hazel C. Youngberg Trustees distinguished professor of economics, Ohio State University

Kyle Moore, senior policy analyst, U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee

Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, co-founder and CEO, the Sadie Collective

Mark Paul, assistant professor of economics, New College of Florida

William E. Spriggs, chief economist, AFL-CIO

Fanta Traore, co-Founder and COO, the Sadie Collective

Valerie Wilson, director, program on race, ethnicity, and the economy, Economic Policy Institute

Jhacova Williams, economist, Economic Policy Institute

Naomi Zewde, assistant professor, Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy, City University of New York (CUNY) Hunter College