The Washington Center for Equitable Growth today announced a set of 14 research grants to scholars seeking evidence on key issues related to economic inequality and growth. The research, chosen in a competitive process with vetting by outside academics and approved by our Steering Committee, will be conducted by faculty members at leading U.S. colleges and universities.

Download File2019-grantee-announcement

Equitable Growth also announced 13 research grants to doctoral students, as well as two resident scholar positions to doctoral students. A total of $1.064 million in grants was awarded.

The topics of the funded research are central to addressing the challenges faced by U.S. workers and their families. They range from how firms set wages and the power workers have in demanding fair pay, to the economic effects of antitrust enforcement and mergers. This is our sixth class of grantees. Since our founding in 2013, we have funded nearly $5 million to nearly 200 scholars.

Equitable Growth supports research to better understand the channels through which inequality affects growth and to provide evidence for policies that can address inequality and ensure strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth. We’re dedicated to bridging the gap between academia and policy by making sure research is relevant to today’s policy debates, and by informing policymakers of cutting-edge research.

Equitable Growth funds research in four categories, which the organization explained in its recent Request for Proposals:

- Human capital: How does economic inequality affect the development of human capital, and to what extent do aggregate trends in human capital explain inequality dynamics?

- Macroeconomic policy: What are the implications of inequality for the long-term stability of our economy and its growth potential?

- Market structure: Are markets becoming less competitive and, if so, why, and what are the implications for productivity, investment, labor markets, labor power, and economic growth?

- Labor market: How does the labor market affect equitable growth? How do inequality and productivity affect the labor market?

Following are the researchers and the research Equitable Growth has awarded grants to this year.

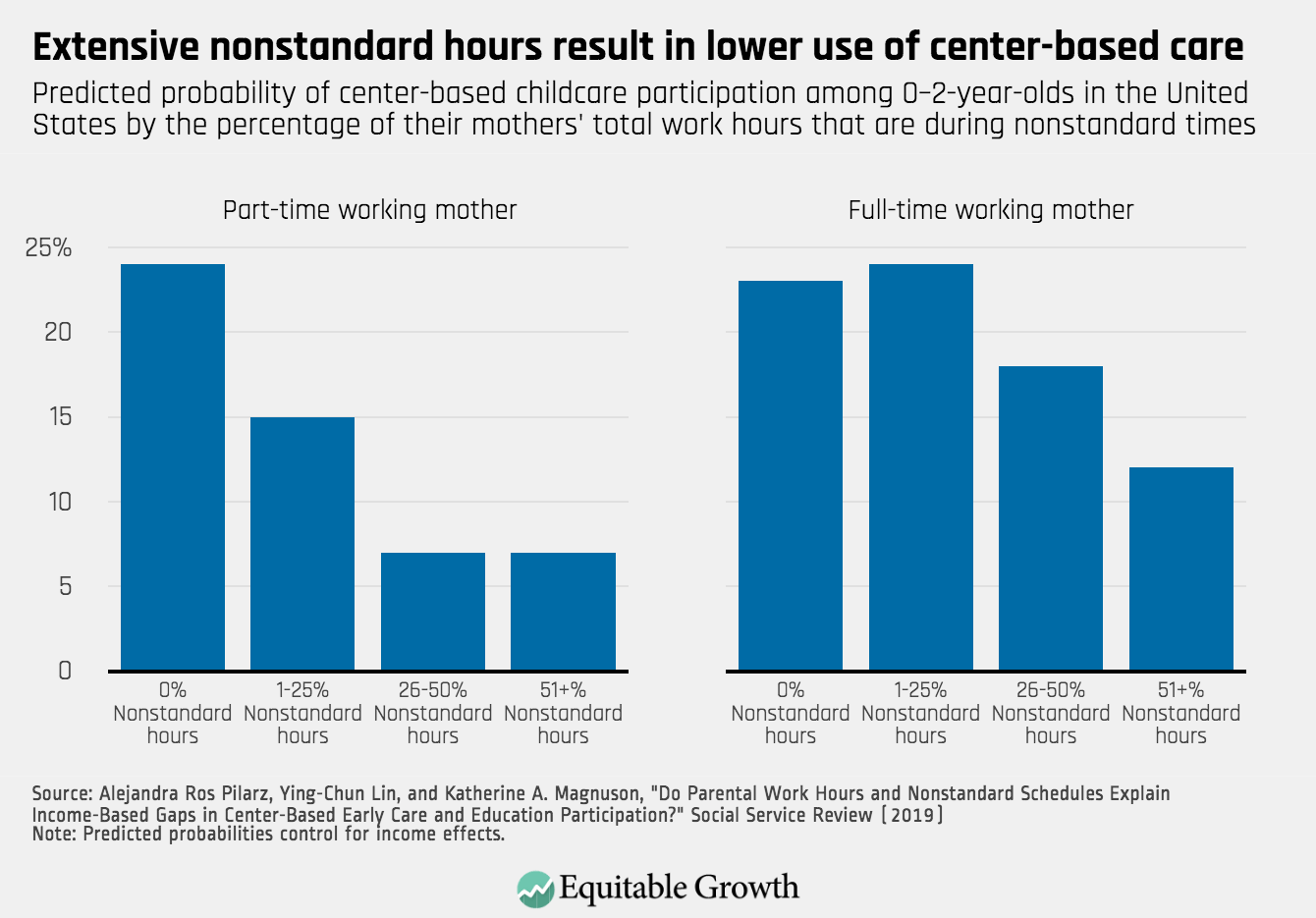

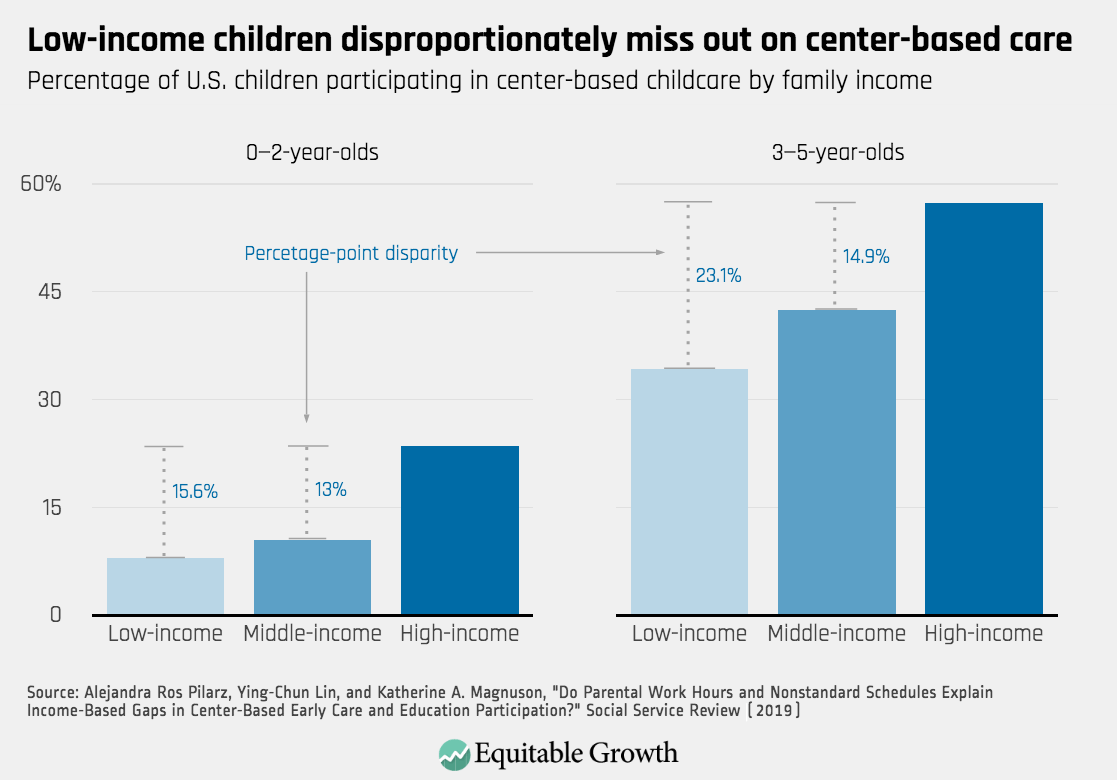

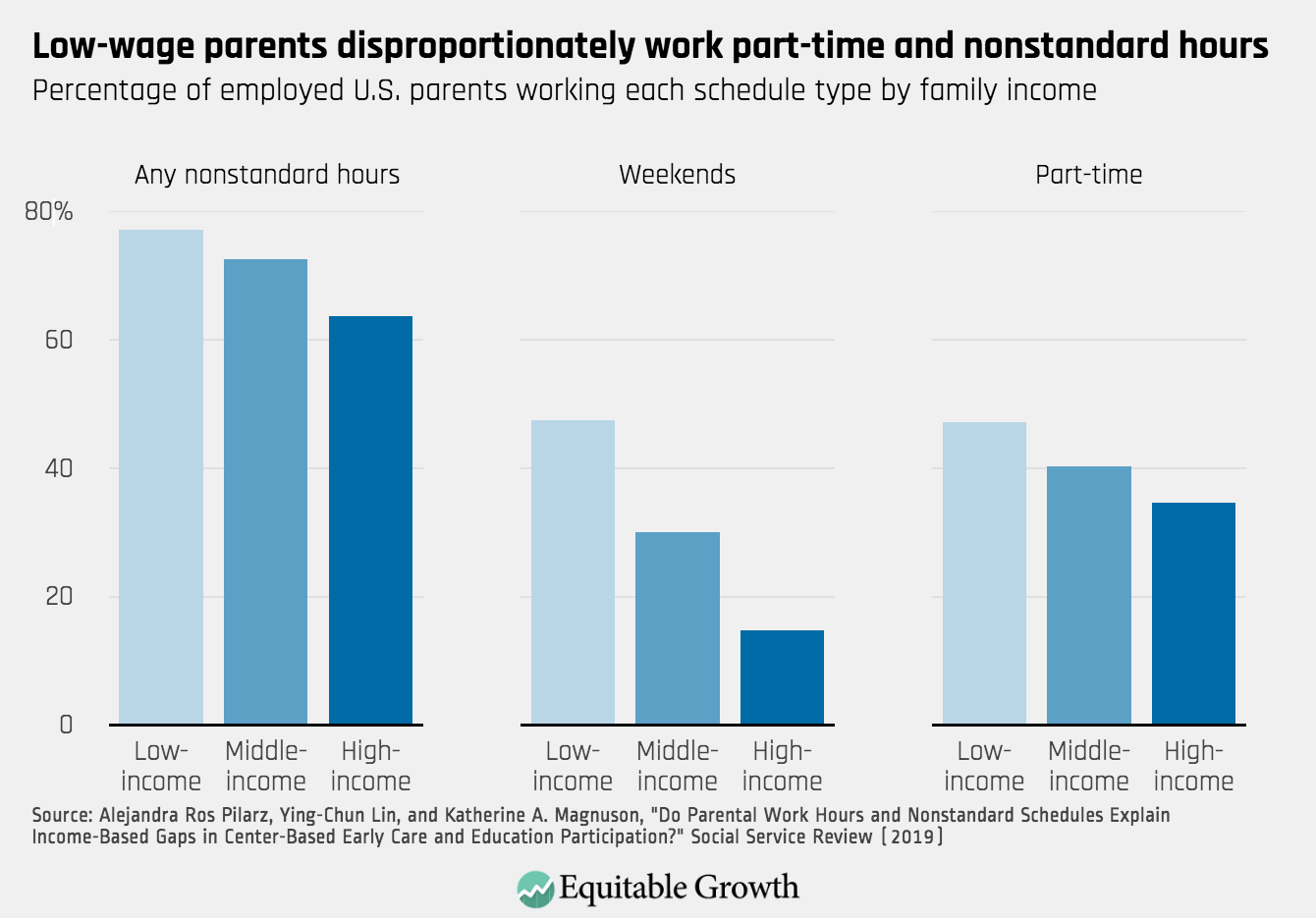

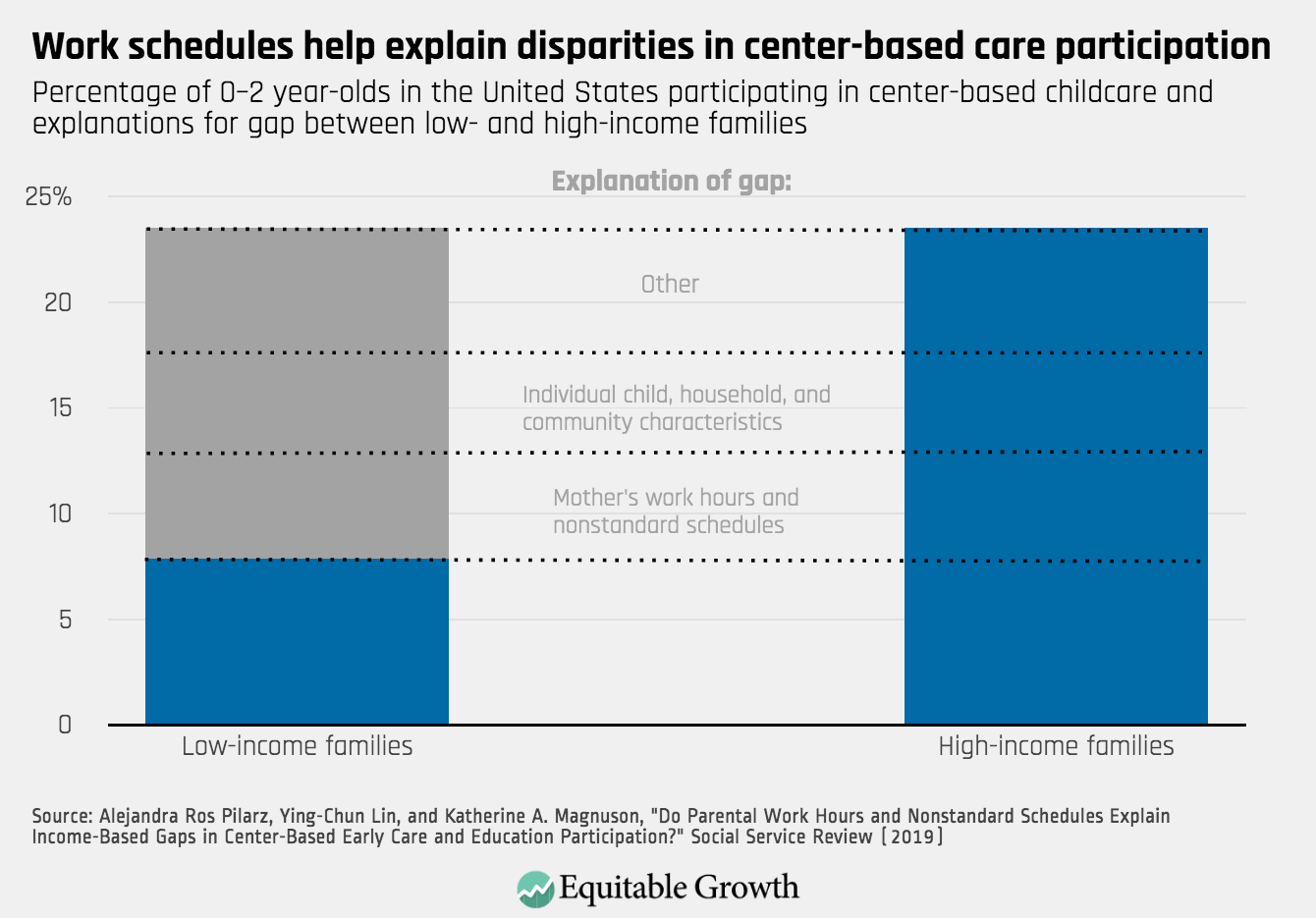

Two projects were funded on the subject of schedule stability for workers, an area that is gaining increasing attention for its impact not only on the lives of workers and their families, but also on the well-being of the companies that rely on those workers. The work will build on existing research that Equitable Growth has funded in this area.

Duke University researcher Anna Gassman-Pines and Columbia University researcher Elizabeth Ananat will identify the consequences of scheduling regulation on workers with young children. Using daily diaries compiled by workers (a more accurate tool than survey questions), they will evaluate the impact of the Philadelphia Fair Workweek Standard, which was enacted in 2018 and will take effect in 2020.

Erin Kelly, Hazhir Rahmandad, and Alex Kowalski, all of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, will collaborate with a warehousing firm to study the impacts on both workers and the firm of unpredictable scheduling. They will document the risks of certain schedules for workers’ health and well-being, as well as the relationships between schedules and worker turnover, absenteeism, and productivity. They will also develop an experiment that provides workers with greater control over their schedules and measure the effects on worker well-being and firm productivity.

Another two grants focus on minimum wages.

The University of Michigan’s Nirupama Rao and Max Risch will study how firms accommodate increases in the minimum wage, with a focus on changes in employment and income. They will examine which kinds of workers, if any, lose or gain employment following increases in the minimum wage and how the incomes of covered and uncovered workers, as well as those of firm owners, are affected.

Jennifer Romich, Scott Allard, Mark Long, and Heather Hill, all of the University of Washington, will develop a database by linking state administrative data that will enable researchers to analyze the impact of minimum wage increases and other policy changes in the state of Washington on household income and participation in government programs.

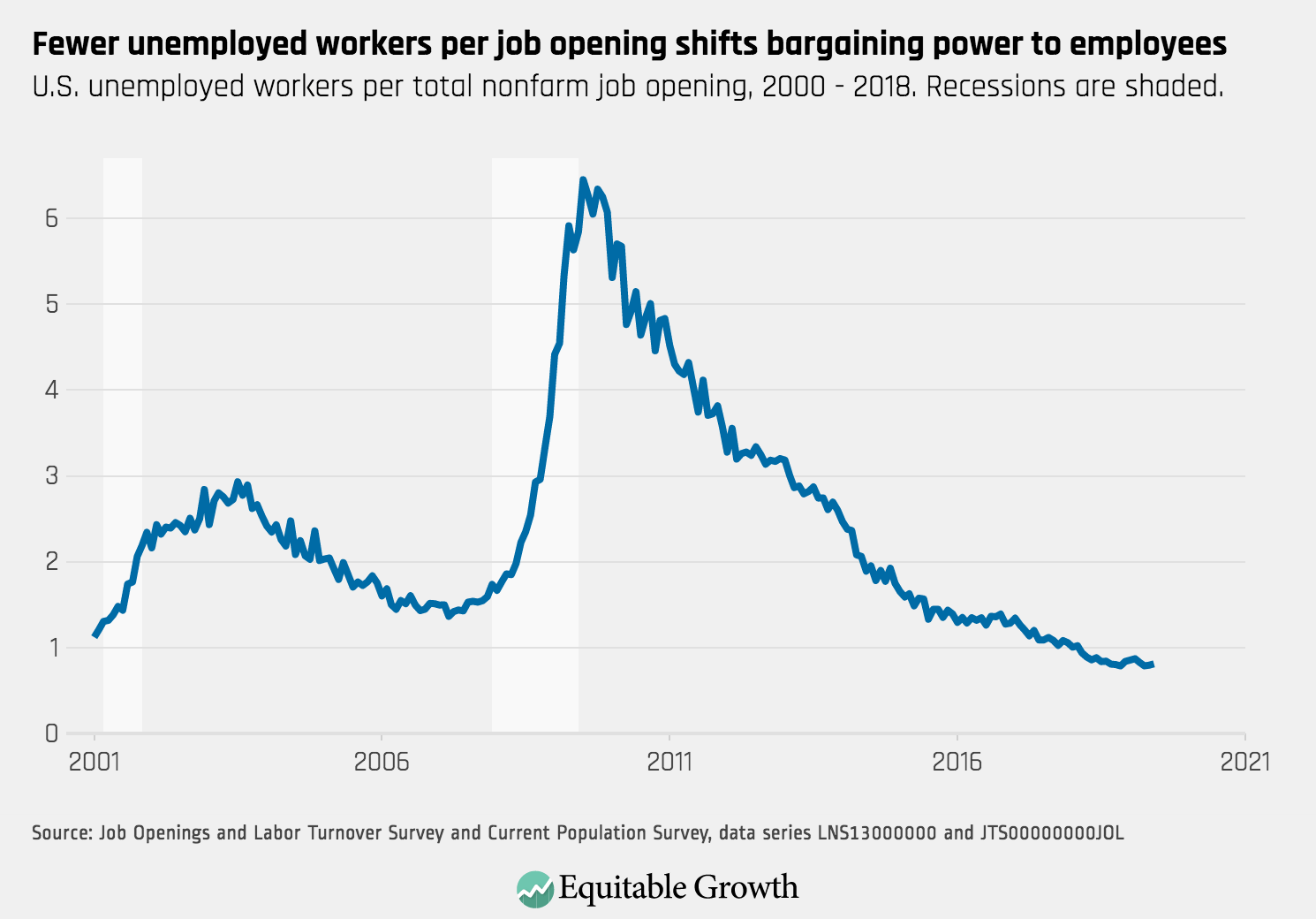

In addition to minimum wage laws, previous research tells us how important firms are in determining worker pay. A number of grants will explore the determinants of worker wages.

In a study of how firms set wages, David Weil of Brandeis University and Ellora Derenoncourt of Princeton University will examine the degree to which broad wage increases by large employers affect the wage-setting practices of smaller businesses. They will look at the impacts of such actions as minimum wage increases by Amazon.com Inc. and Walmart Inc. and an executive order issued by President Barack Obama that raised the minimum wage paid by federal contractors.

MIT’s Simon Jäger and Benjamin Schoefer of the University of California, Berkeley, will study the impact of shared corporate governance—workers participating in the management of the companies where they work. This is not so common in the United States but is the law in some other countries, including Germany. Their project will use reforms in the German law to analyze the effects of shared governance on such outcomes as wages, distribution of profits, and pay equity within firms.

David Berger of Duke University, Kyle Herkenhoff of the University of Minnesota, and Simon Mongey of the University of Chicago will use government data to help determine the extent to which corporate mergers might have a monopsonistic effect on competition in the U.S. labor market—that is, whether mergers have given firms, rather than markets, the power to set wage levels. They will look at the effects on compensation and numbers of jobs for low- and high-wage workers and more broadly at labor’s share of business income. They will also study long-term effects on earnings for those who lose their jobs in the wake of a merger.

Finally, MIT’s Nathan Wilmers will seek to improve understanding of job mobility by using data sources to distinguish between those who move to a new job within their current employer and those who take a job with a new employer. The project may help to explain whether or not increased within-organization job mobility is disproportionately benefiting high-income/high-skill workers and therefore contributing to inequality in the labor market.

In order to better understand obstacles to rejoining the labor market for formerly incarcerated individuals, as well as the benefits of job training programs, Peter Blair of Harvard University and Morris Kleiner of the University of Minnesota will examine how state laws governing the ability of ex-offenders to obtain an occupational license affect their employment prospects and wages over time. The researchers will create a publicly available database of statutory and administrative laws throughout the United States on the subject.

In addition to the need for higher wages and enhanced worker bargaining power, evidence points to the necessity of effective government programs that provide a strong safety net to support individuals and families in need and help unemployed workers while they seek new jobs. In order to provide evidence on what works, we have awarded a grant to Hilary Hoynes of the University of California, Berkeley to study the impact of different types of welfare reforms. She will examine the long-run results of a series of experiments with low-income workers and families conducted in the 1980s and 1990s by MRDC, a public policy research organization. The experiments included various forms of employment incentives and subsidies, job training and search assistance, time limits, and sanctions. Her research will analyze their effects on such outcomes as earnings and employment, marriage, mortality, and later participation in welfare programs by adults and, importantly, their children.

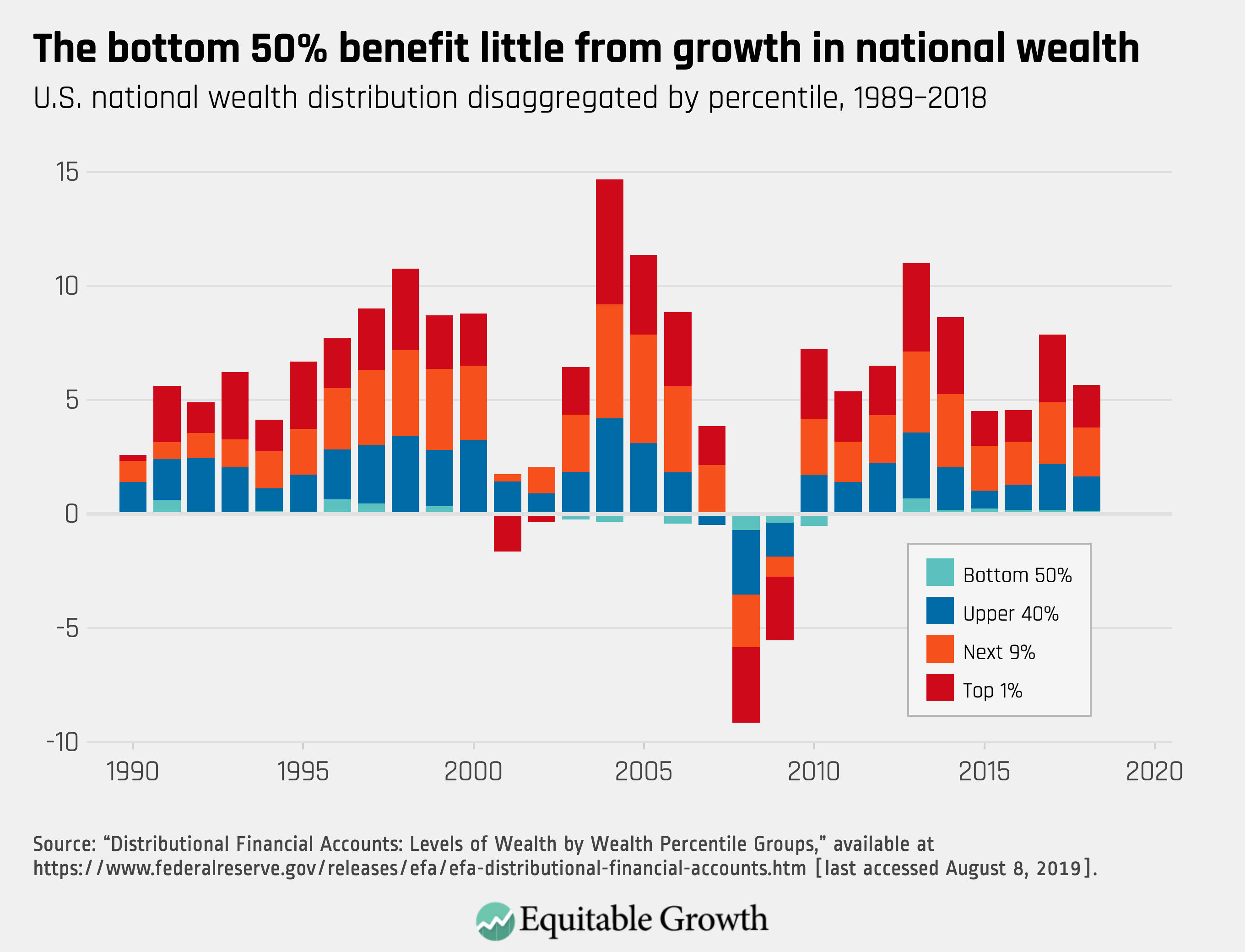

Equitable Growth is equally interested in how markets are functioning and the distribution of economic growth. Equitable Growth is therefore supporting research into markets and the returns of market gains.

Juan Carlos Suarez Serrato of Duke University, Mark Curtis of Wake Forest University, and Eric Ohrn of Grinnell College will explore the forces that determine whether business income goes to capital or to labor, and how that affects inequality. Building on previous research on the distribution of benefits from bonus depreciation, a business tax break that was significantly enhanced—temporarily—by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, they will address outcomes such as wage levels and jobs gained or lost for workers of various skill levels. Since this provision encourages mechanization, the research is also an opportunity to examine the impacts of technology on workers.

Constructing a comprehensive database of more than a century and a quarter of federal antitrust enforcement actions is the goal of University of Chicago colleagues Simcha Barkai (also affiliated with the London Business School) and Ezra Karger. They will link these data about Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission actions against firms and individuals between 1890 and 2017 to other government data to measure the effect of antitrust enforcement on economic output.

Examining a more specific market, Randall Akee of the University of California, Los Angeles and Elton Mykerezi of the University of Minnesota will extend their prior work studying business dynamics on and near American Indian reservations. They will focus on how large casinos acting as anchor businesses affect the transportation, food services, retail operations, and lodging industries. The research will not only produce new data on American Indian reservations, which is severely lacking, but also shed light on what economic development policies might be successful in isolated rural areas.

Scott Kominers and Ravi Jagadeesan of Harvard University, Mohammad Akbarpour of Stanford University, and Piotr Dworczak of Northwestern University will carry out theoretical work on the design of markets for goods. Specifically, they will conduct three studies addressing various issues in the context of significant wealth inequality.

Equitable Growth is also awarding 13 research grants to doctoral students in order to build the pipeline of scholars doing research relevant to inequality and growth. Ph.D. students who will receive grants this year are:

Ratib Ali of Boston College, Peter Fugiel of the University of Chicago, Ingrid Haegele of UC Berkeley, Isaac Jabola-Carolus of The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, Maningbe Keita of Johns Hopkins University, Daniel Mangrum of Vanderbilt University, Jacob Orchard of the University of California, San Diego, Krista Ruffini of the UC Berkeley, Lauren Russell of Harvard University, Anna Stansbury (and co-investigator Gregor Schubert) of Harvard University, Conor Walsh of Yale University, Christian Wolf of Princeton University, and Samuel Young (and co-investigator Sean Wang) of MIT.

Two doctoral students will spend an academic year as resident scholars at Equitable Growth, where they will have an opportunity to pursue their research and gain experience in how research can inform the policy process. They are Angela Lee of Harvard University and Umberto Muratori of Georgetown University.

Equitable Growth’s academic program is a year-round process. Now that the 2019–20 grants have been announced, our staff and Steering Committee will get to work on the RFP for our next grant cycle. And going forward, we will publish new research from our grantees, make sure policymakers and the public see the results, and continue to build a bridge between those who make policy and those who can provide the evidence they need to do so in a way that supports an economy that works for all Americans.