In the United States, Labor Day, which falls on the first Monday of September, is when we honor the history of the U.S. labor movement in striving for benefits and empowerment of workers across the economy. Strikes play an important role in empowering workers vis-à-vis their employers. By withdrawing their labor power, workers are able to balance the scales against the owners of capital, who rely on workers for production and providing services. Strikes have declined in frequency, popularity, and success over the past four decades, yet today, amid rising economic inequality, they are once again becoming an important tool in exercising worker power to ensure that the gains of profitability and economic growth can be broadly shared.

The history of strikes in the United States

Washington University in St. Louis sociologist Jake Rosenfeld examines the role of work stoppages in his recent book What Unions No Longer Do, and finds that strikes at large firms began declining in the mid-1970s, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Work Stoppages file. Rosenfeld then digs deeper to estimate the trends of strikes at firms both large and small by calculating a broader measure using data from the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service from 1984 to 2002. He finds a peak in strikes in the late 1980s and then a stark decline after.

The decline of strikes is a result of a variety of factors. One is the increased use of replacement hires, especially after the PATCO strike of 1981, when President Ronald Reagan summarily fired 11,000 air traffic controllers who were striking for higher pay and a reduced work week. President Reagan quickly replaced those striking workers with 4,000 air traffic control supervisors and Army members, sending a powerful message to U.S. workers about the use of strikes in labor disputes.

But even before this historic turning point, the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947 limited the ability of workers to strike. This included restrictions on secondary boycotts and picketing, both of which make striking especially difficult in today’s increasingly fissured workplace, where you cannot strike against the corporation that is at least partly responsible for your workplace conditions but not technically your direct employer. For example, workers at the franchises of McDonald’s Corporation who attempt to unionize are not protected by the Fair Labor Standards Act when picketing against McDonald’s because they are, most commonly, the employees of a franchisor, rather than of the main corporation.

These factors, along with a general increasing business hostility toward unions and lack of enforcement of labor protections, have ultimately made strikes less effective as a tool for collective bargaining in the United States.

Increasing interest in unions among U.S. workers today

At the same time, there is an increasing consensus today that unions are a positive force for increasing worker power and balancing against economic inequality. In polling of support for unions and specific aspects of collective bargaining, Equitable Growth grantee Alex Hertel-Fernandez of Columbia University, along with William Kimball and Thomas Kochan of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, find that support for unions has grown overall, with nearly half of U.S. workers in 2018 saying they would vote for a union if given the opportunity. This is a significant increase from one-third of workers supporting unionization in 1995. According to their research, workers primarily value unions’ role in collective bargaining and ensuring access to benefits such as healthcare, retirement, and unemployment insurance.

Strikes have historically been one of the strongest tools used by unions to ensure they have power to engage in collective bargaining. But striking was viewed as a negative attribute in the survey done by Hertel-Fernandez, Kimball, and Kochan. Yet, when they presented workers with the hypothetical choice of a union exercising strike power with other attributes of unions, such as collective bargaining, support increased.

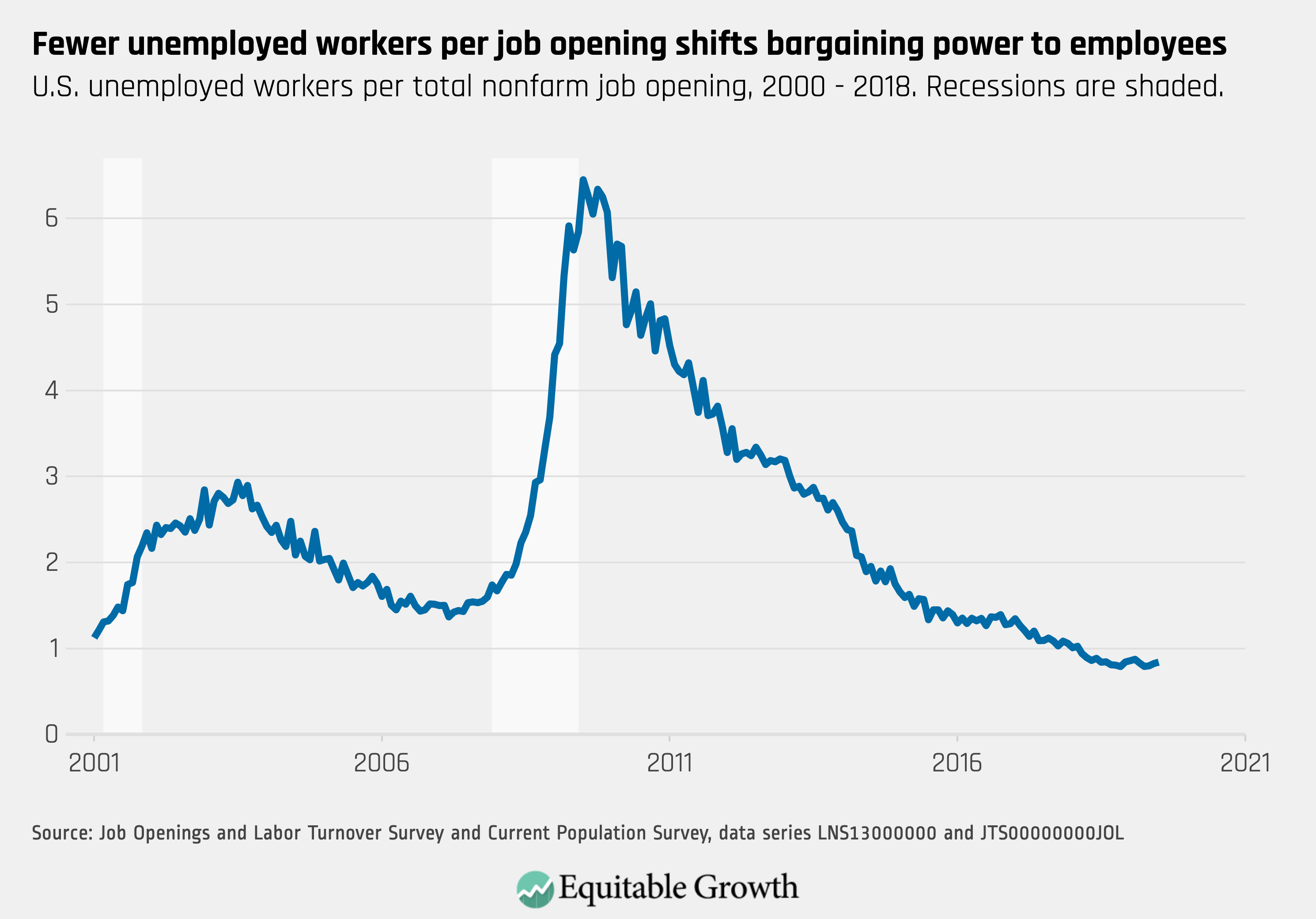

But strikes, of course, do not take place in a bubble. The wider climate of worker bargaining power and institutions that support labor organizing plays a role in making this historically crucial tool effective again. So, too, does the power of employers to resist these organizing efforts when the labor market lacks competition that would increase worker bargaining power.

The role of monopsony power in the U.S. labor market

Monopsony power is a situation in the labor market where individual employers exercise effective control over wage setting rather than wages being set by competitive forces (akin to monopoly power, where a limited number of firms exercise pricing power over their customers.) In a new Equitable Growth working paper by Mark Paul of New College of Florida and Mark Stelzner of Connecticut College, the role of collective action in offsetting employer monopsony power is examined in the context of institutional support for labor. Paul and Stelzner construct an abstract model with the assumption of monopsonistic markets and follow the originator of monopsony theory Joan Robinson’s insight that unions can serve as a countervailing power against employer power.

Their model shows that institutional support for unions, such as legislation protecting the right to organize, is necessary for this dynamic process of balancing employers’ monopsony power. In an accompanying column, the two researchers write that they “find that a lack of institutional support will devastate unions’ ability to function as a balance to firms’ monopsony power, potentially with major consequences … In turn, labor market outcomes will be less socially efficient.”

In short, policies and enforcement that support collective action such as strikes not only creates benefits for workers directly but also addresses a larger problem of concentrated market power.

The return of strikes in the U.S. labor market

Within the past few years, strikes have been revived as a bargaining tool. “Red for Ed” became the name referring to teachers strikes that took place across traditionally conservative right-to-work states. Beginning with the closure of all schools in West Virginia in 2018 following 20,000 teachers across the state walking out, this movement spread to Oklahoma, Kentucky, Arizona, and Colorado, among other places. These strikes were led by rank-and-file union members, rather than by union leadership, rendering them illegal under the Taft-Hartley Act, which prohibits so-called wildcat strikes. These strikes led to significant gains for these public-sector workers through organizing against policymakers rather than direct management.

Before Red for Ed, the “Fight for Fifteen” movement starting in 2012 and “OUR Walmart” starting in 2010 exemplified labor organizing in new mediums by conducting worker-led actions against large corporations that directly employ or control the employment (as in the franchisor-franchisee model) of low-wage workers. The efforts of Fight for Fifteen directly impacted New York state’s minimum wage increase to $15 per hour and has paved the way for a national movement for a higher minimum wage. OUR Walmart led walkouts and Black Friday protests in the years leading up to Walmart’s decision to increase wages.

Many structural changes, such as the fissuring of the workplace, have reduced the ability of private-sector unions to make gains against employers, yet these strikes and labor actions represent an opportunity for growth. With the U.S. labor market increasingly dominated by the services sector, these strikes were conducted by workers whose jobs cannot move elsewhere and whose work we interact with in our daily lives. Ruth Milkman of the City University of New York describes these labor actions as similar to those that existed before the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 protected the right strike (before these rights were subsequently chipped away by the Taft-Hartley Act 20 years later) in order to unionize.

With popular and successful strikes in unexpected places, what will the role of strikes be in the future? Will workers continue recognize the strength of the strike and other labor actions, and will policymakers and enforcers make it a successful tool for increasing worker bargaining power? Research by Alex Hertel-Fernandez, Suresh Naidu, and Adam Reich of Columbia University looked at the response to strikes following the Red for Ed movement in conservative states and found that residents of areas affected by the teacher walkouts broadly supported the strikes, with 39 percent saying they strongly supported the walkouts and another 27 percent somewhat in support of the walkouts, including half of self-identified Republicans supporting the strikes.

What’s more, the three researchers found that families that learned about them from their teachers or directly from the union had even stronger support for the strikes, compared to those who learned about them from other sources, such as talk radio. First-hand knowledge of strikes increases support for them.

In addition to Hertel-Fernandez’s work showing broad support for unions generally and increasing support for bold labor actions, more policymakers and advocates are providing much-needed proposals on how to foster a robust U.S. labor market and strengthen institutions that would make collective action more successful. Emblematic of this is Harvard Law’s Labor and Worklife Program’s Clean Slate Project, led by Sharon Block and Ben Sachs of Harvard University, which gathers academic experts and labor organizers to develop strong proposals that would increase worker bargaining power. Multiple 2020 presidential campaigns have followed suit, with new proposals to boost unions.

Conclusion

Unions in the United States are at their lowest level of density since they became legal around 80 years ago, with 6.4 percent of private-sector workers in unions today. Yet there is increasing energy for bringing back this crucial force to balance the power of capital and ensure the fruits of economic growth are more broadly shared among everyone who creates it. Strikes are a compelling tool for dealing with rising U.S. income and wealth inequality—just as they were in an earlier era of economic inequality, when unions first gained their legal stature in the U.S. labor market.