When U.S. workers fall ill, it can be challenging to balance medical needs and job responsibilities. For short sicknesses, such as a cold or the flu, several days of rest at home might be all that is needed. With more significant illnesses or injuries, however, it may be impossible for a worker to return to the job for several weeks or even months. These workers face a significant dilemma. How can they take time to focus on their health without facing financial hardship? Even in times of illness, bills and expenses continue to add up. For these individuals, paid sick days are not enough to cover needed time off. Paid medical leave provides partial wage replacement to workers who need recovery periods longer than a few days.

Download FileWhat is paid medical leave and how does it support U.S. workers’ health and the U.S. economy?

Currently, there is no federal paid medical leave program. Congress has failed to provide permanent paid medical leave under the false perception that costs to business outweigh benefits to individuals, families, and the U.S. economy as a whole. This factsheet reviews how paid medical leave differs from sick leave and what the research says about its likely impact on health and economic outcomes.

How paid medical leave differs from paid sick leave

Paid medical leave is defined as leave to care for one’s own physical illness or injury over a period of weeks or months. This type of leave is valuable for workers who need extra time away from their job but expect to return to the workforce after recovering. This is distinct from shorter-term leave, known as paid sick leave or sick days, and disability programs for people who are unable to return to the workforce. Specifically:

- Paid medical leave is used to address serious illnesses and injuries, seek medical care, and recover before returning to work. Workers may access paid medical leave through private and public insurance programs, including state-level paid family and medical leave programs, private employer benefits, and private short-term disability insurance. Eight states and the District of Columbia have passed laws establishing social insurance programs that provide paid medical leave. Leave length ranges from 2 weeks to 52 weeks.1 Workers accessing paid leave through these sources are entitled to partial wage replacement. Some state programs provide job protection for those on leave. In other states, workers may be eligible for job protection under a patchwork of federal and state laws.

- Some workers can take paid sick days for leaves of shorter duration. Paid sick days are offered voluntarily by many employers, and laws in many states and municipalities guarantee workers the right to earn paid sick days. Paid sick days are more common than paid medical leave, but many workers still do not have access. More than 70 percent of workers have access to paid sick leave, but many vulnerable workers do not.2 Less than half of part-time workers and low-wage, private-industry workers have access to this benefit.3 Workers with sick days typically receive their regular wage while at home and return to work in a handful of days.

How paid medical leave might improve health outcomes

Research on the impact of paid medical leave on health outcomes is still emerging. Evidence to date suggests there are several different mechanisms through which paid medical leave may have an effect on health outcomes. These include better health management, earlier treatment, greater healthcare utilization, reduced financial stress, and improved public health. Specifically:

- Employees who can take time away from work are better able to manage their health. One of the strongest signals that paid medical leave may impact health outcomes comes from research on paid sick days. Access to paid time off to care for one’s health is associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality across many conditions.4 When workers have access to paid sick days, they are more likely to seek preventative medicine and visit the emergency room less.5 Time away from work to manage one’s health can have long-term benefits and help workers avoid health shocks later in life.6 Those requiring paid medical leave already have a significant illness or injury, but access to paid leave allows them to focus on managing their conditions without the stress of work responsibilities or financial uncertainty.

- Wage replacement reduces financial stress and allows workers to focus on getting well. Taking time away from work to address a medical condition reduces an individual’s income, adding stress on workers who are already concerned with their health. Research on programs that reduce financial stress through monetary benefits suggest that they can lead to positive health outcomes. For example, increases in Social Security Disability Insurance, or SSDI, payments among low-income individuals was associated with a decreased annual mortality rate of 0.1 to 0.25 percentage points.7 Increasing Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, benefits has been linked to better maternal health, which researchers partly credit to reductions in stress.8 To the extent that paid medical leave also reduces financial stress through wage replacement, it could lead to improved health for workers.

- Access to paid time off reduces the spread of disease and improves public health. Research on local and state sick leave mandates in the United States found a significant reduction in the general flu rate after the mandates were implemented.9 When workers have access to paid sick leave, they are less likely to show up to work while sick and risk the spread of an illness to their co-workers. As a result, their co-workers stay healthy and productive. It is possible that paid medical leave could have similar impacts for public health. During a public health crisis, paid medical leave helps workers take time off to recover and remain in isolation to slow the spread of the virus.

How paid medical leave might improve economic outcomes

Serious medical conditions that require time away from work can pose a threat to workers’ economic well-being. They can lead to an immediate reduction in income, an increase in out-of-pocket expenses, and the risk of losing their jobs. Paid medical leave could help address these challenges, but existing research on the direct effects of paid medical leave specifically is scant. But related research on sick leave, income security, occupational health, and disability programs provide insights into how paid medical leave might positively affect economic outcomes. Specifically:

- Serious medical conditions can suddenly threaten economic stability. Unpaid time from work causes an immediate reduction in income that many families cannot afford. In addition to this income shock, workers who need medical leave may incur high out-of-pocket expenses. A survey of workers with temporary disability pay found that 22 percent of their healthcare expenses were out of pocket.10 Overall, one-fifth of adults have large and unexpected medical bills, often totaling between $1,000 to $4,000.11 Research shows that cancer patients without paid sick or medical leave report significantly higher financial burdens and are more likely to borrow money and leave their jobs.12

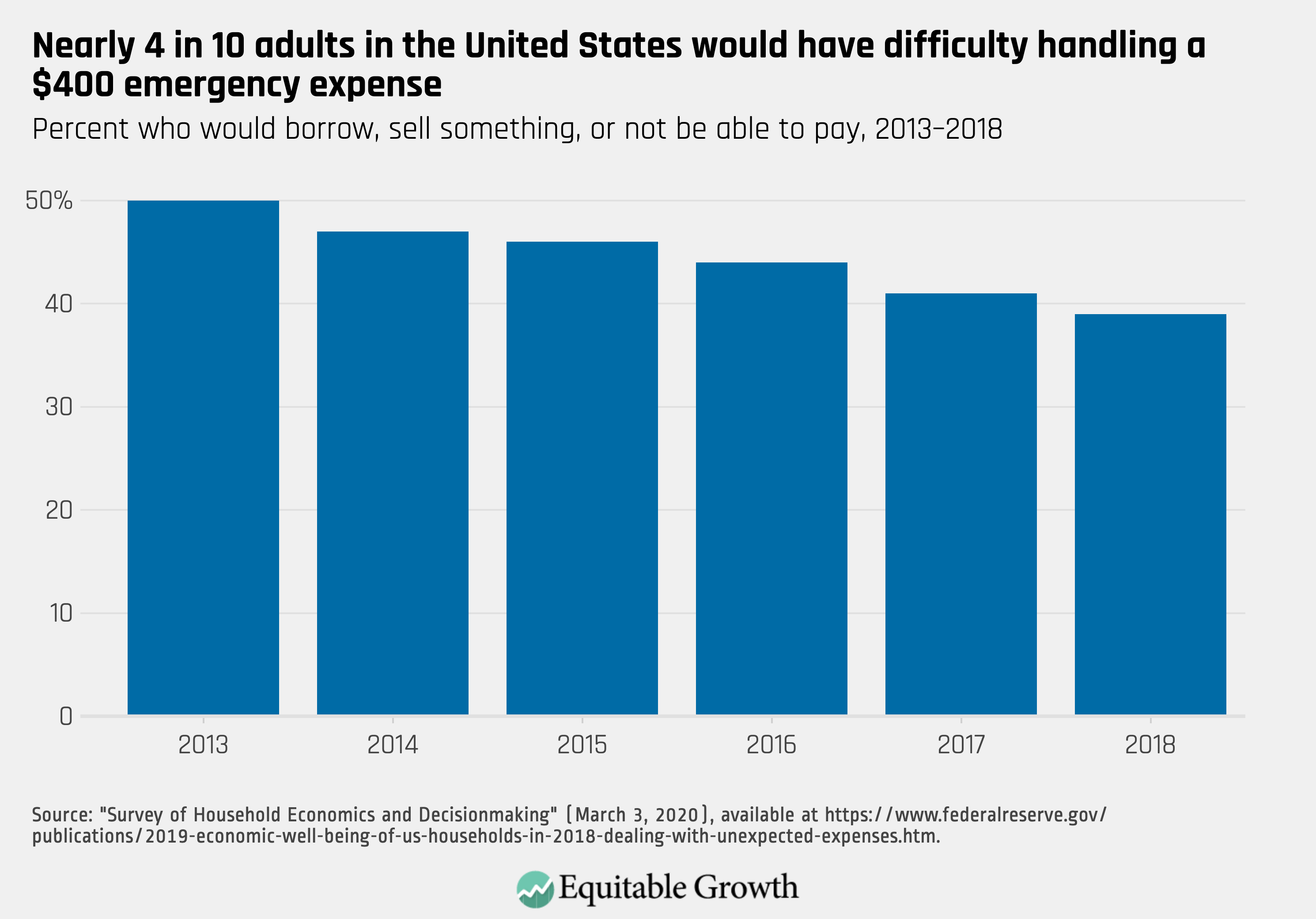

- Many families are unprepared for such expenses, but paid leave can ease the blow. One in three families have no personal savings, and 41 percent of families cannot afford a $2,000 unexpected expense.13 Families facing an income shock with little or no savings are at increased risk of eviction or missed house and utility payments. Even a small amount of financial support can help. While 21.1 percent of families with savings of $249 or less missed a housing payment, that percentage falls to 15.2 percent when families have savings of between $250 and $749.14 Wage replacement through paid medical leave may not erase the stress or pain of an illness, but it could provide the necessary boost to help families weather a health-related income shock.

- Access to paid medical leave may reduce the risk of job separations, at least in the short term. One study found that access to paid sick days decreases the probability of job separation by 25 percent, suggesting paid medical leave may have a similar effect.15 And paid medical leave could improve overall U.S. labor force participation.16 A study of nine cities and four states implementing paid sick leave benefits found no significant effects on employment or wages.17