When U.S. policymakers seek to restore the U.S. economy in the wake of the coronavirus recession, what will constitute success? Returning the economy to its prepandemic state is not sufficient. It’s not even desirable. Yes, unemployment was low, and job growth was strong. But that economy was also characterized by pervasive economic inequality, low productivity, and inflated asset prices. That economy was being kept afloat mainly by the Federal Reserve’s policy of maintaining a historically low rate of interest.

The Fed was forced into keeping interest rates low by years of misguided fiscal policy. When it was convenient, the need to control budget deficits was made the highest priority and used as an argument against the kind of investments that build a strong economy. Yet the deficit became irrelevant when tax cuts, especially tax cuts for the wealthy, were on the table. As policymakers seek ways to recover from the coronavirus recession, we will need to do more than just provide healthcare and replace lost incomes until the economy is “back.” The focus of fiscal policy during this recovery should be to invest—and invest a lot—in human capital, infrastructure, and scientific research.

When the coronavirus hit the U.S. economy hard in March, conventional wisdom had it that the economy was as strong as it had been in generations, with low unemployment and a thriving stock market, and that it took a global pandemic to bring it down. Some leaders, and too often the media, use the stock market as a proxy for the strength of the economy. But that is a symptom of what was wrong with our economy and economic policymaking before the new coronavirus hit our shores, spreading the COVID-19 disease in its wake—and what we need to avoid in policymaking going forward.

The new U.S. economy that policymakers should aim for also should feature low unemployment, achieved through higher productivity created by public and private investments powering broad-based growth. The new economy should create well-paying jobs with strong benefits for the many, not the few. The gap in benefits such as paid sick days and family leave is clearly evident amid this continuing public health crisis. The new economy should be stronger and more resilient than anything we saw in the decades leading up to this crisis, providing policymakers understand their past mistakes and do things differently going forward.

What, specifically, do policymakers need to do to achieve this new economy? First, some context.

The Federal Reserve lowered interest rates at the onset of the Great Recession and has kept rates near zero for most of the time since. In fact, the Fed discount rate has not been this low for a sustained period in about 70 years. This is partly due to market trends and partly a result of explicit monetary policy. Keeping in mind that interest rates are essentially the price of borrowing money, downward pressure on rates was a result of slow productivity growth, which reduces the demand among businesses for credit so they can invest, and an aging population, which increases the supply of saving. These two factors have a number of important implications, including:

- The Fed’s traditional weapon for combatting recessions—lowering interest rates by several points—is depleted. Practically speaking, you can’t lower interest rates much below zero.

- The return to risk-free saving was reduced. This affected individual savers seeking to secure their retirement savings, as well as institutional investor funds that support guaranteed pension benefits and other forms of annuities. These investors were forced to take greater risks to get positive financial returns or save even more, both of which pose challenges to the economy.

- Lower interest rates reduced borrowing costs for corporations, and they took on excessive debt, including to enrich their shareholders by buying back corporate stock. Stock prices (and other asset values) were overvalued using conventional measures such as the Buffet Ratio, and thus were highly vulnerable to shocks.

While financial markets exerted downward pressure on interest rates, the Fed was forced, before the coronavirus recession, to accommodate that downward pressure to keep the economic recovery on course. And the reason was wrongheaded U.S. fiscal policy. Better fiscal policy, emphasizing federal investment over tax cuts, would have led to higher productivity and a stronger economy. This would have made it possible for the Fed to conduct better monetary policy, meaning the Fed could achieve full employment and stable inflation—the U.S. central bank’s “dual mandate”—without the inherent financial market valuation issues and instability associated with artificially low interest rates.

Since the 1980s, the narrative that has governed U. S. fiscal policy has been that budget deficits are bad for the economy, and they are caused by excessive spending. Tax cuts are always good for the economy. And what about the deficits they create? Deficits caused by tax cuts are okay, and anyway, tax cuts pay for themselves—or so goes the supply-side argument. As we know, the latter argument has been disproven time and time again.

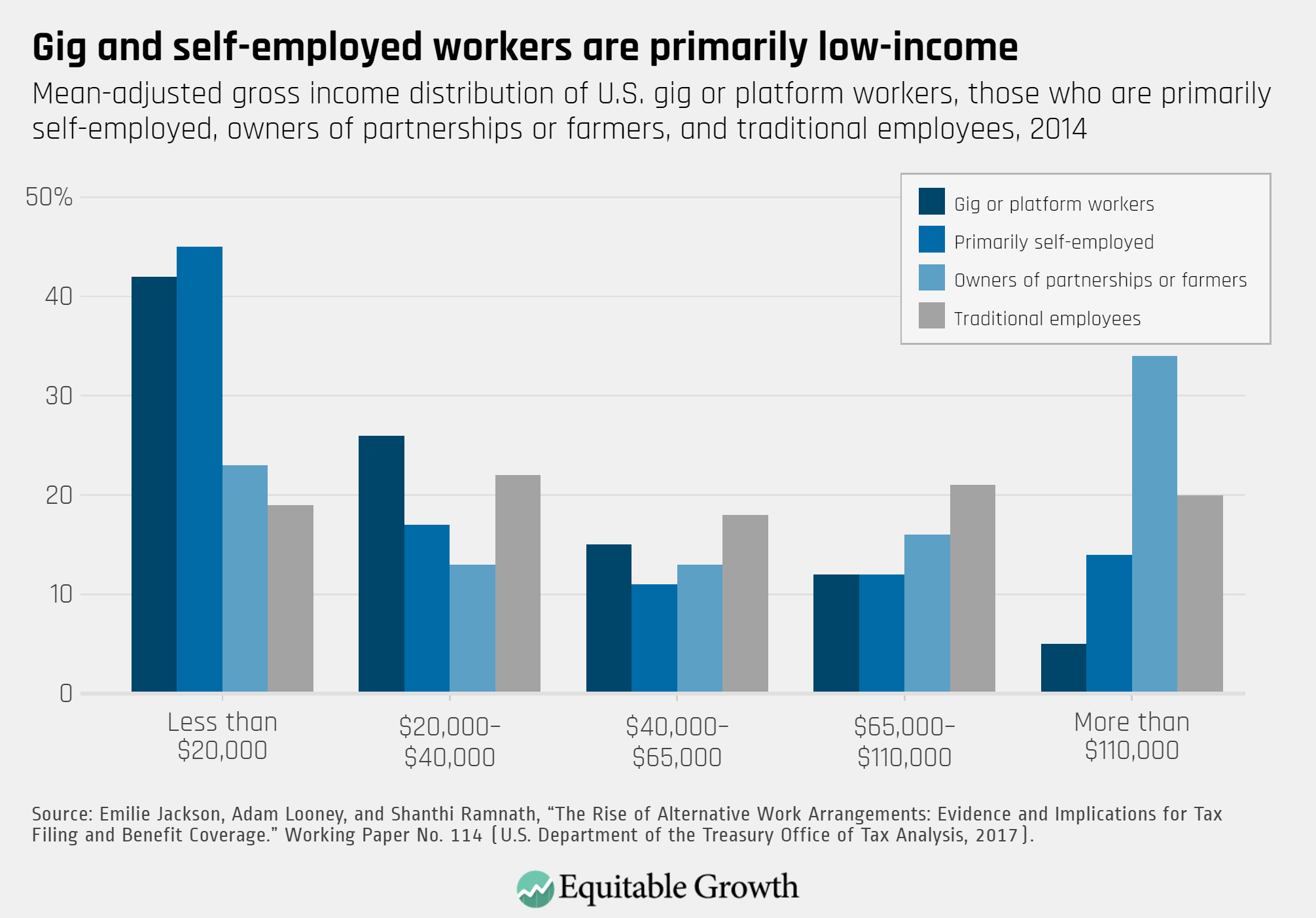

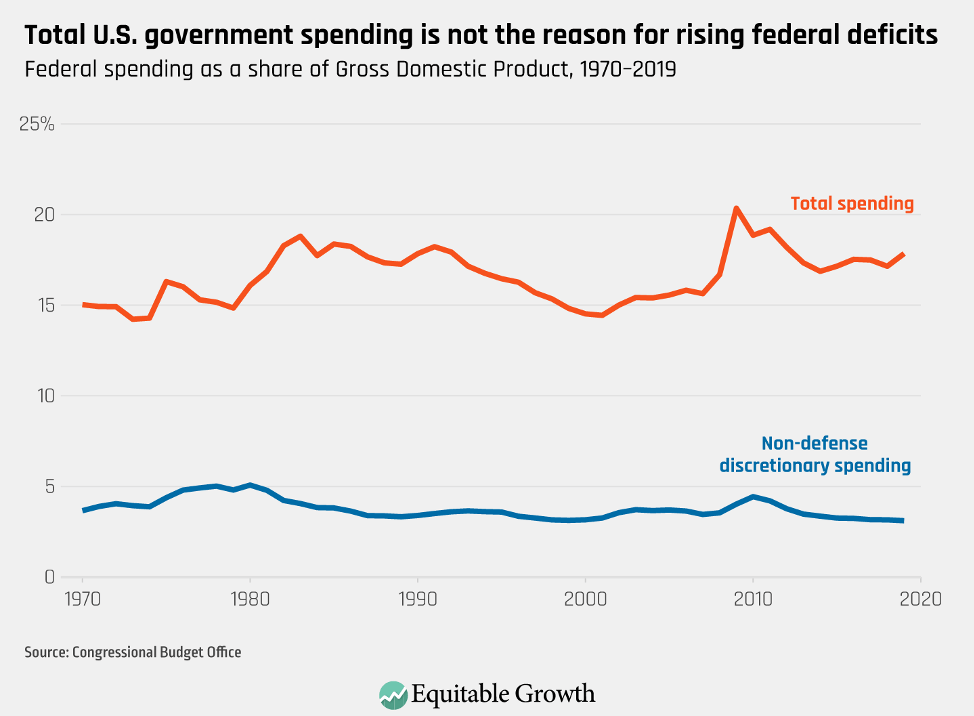

Indeed, examining the composition of federal spending and the composition of federal revenues relative to Gross Domestic Product over the past few decades provides a high-level, evidence-based perspective on this mistaken supply-side narrative. The data clearly reject that narrative that increased government spending is the primary reason for rising government deficits in recent years. Total spending, at about 20 percent of GDP in 2019, is close to its 50-year average. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

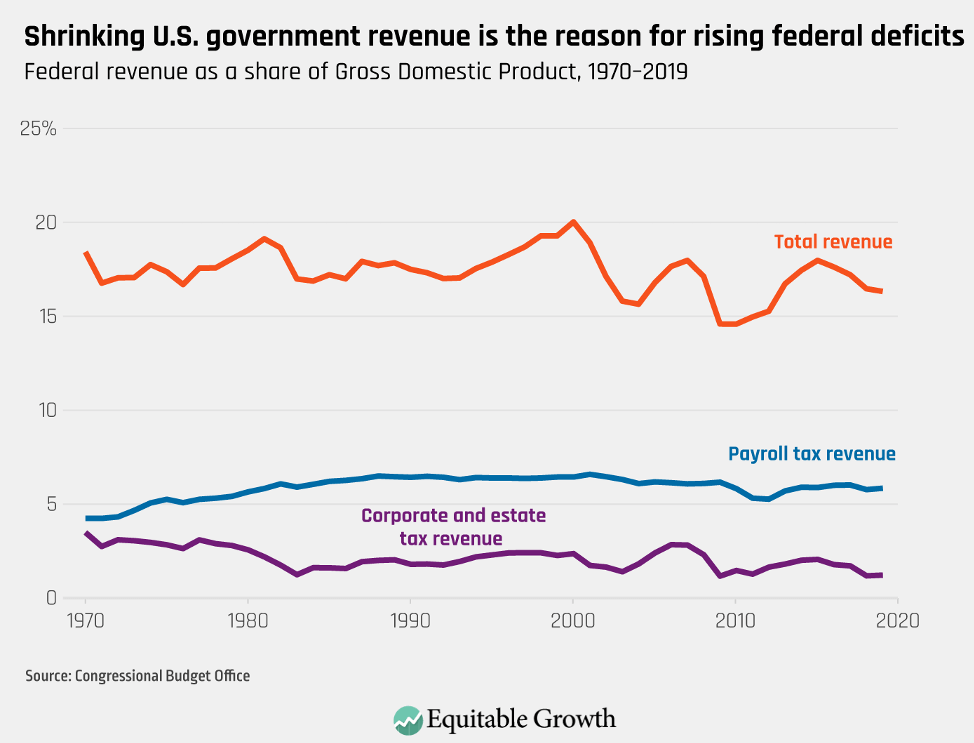

In contrast, total federal revenue relative to GDP, at 16.5 percent in 2019, is historically low. The previous time the economy was comparable to what we experienced in 2019, at the end of the 1990s, revenues were 20 percent of GDP. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

A closer look at the composition of spending in Figure 1 cuts further against the mistaken narrative about rising government spending. The component of spending associated with direct government intervention in the real economy—nondefense discretionary spending—has fallen as a share of GDP in recent decades. The fastest growing categories of outlays are for programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, all of which are generally financed by payroll taxes on the same low- and moderate-wage earners who are the primary beneficiaries.

The increase in payroll taxes used to fund these programs is evident in Figure 2. Thus, another crucial takeaway from this high-level perspective is that the overall decline in total revenues relative to GDP is because corporate, estate, gift, and income taxes have fallen even more than payroll taxes have increased. Deficits are primarily the result of the wealthy and corporations paying less in taxes, not due to workers receiving social insurance benefits for which they are not paying.

Most analysis of fiscal policy focuses on the economic effect of deficits, without regard for why the deficits were created. The trends in the composition of U.S. spending and revenue shown above suggest that all deficits are not created equal. A deficit created by increased nondefense discretionary spending focused on investments in human capital, scientific research, and infrastructure has positive effects on aggregate demand and boosts productivity. Such policies have the potential to reverse the downward pressure on interest rates.

A deficit generated by reducing taxes on capital incomes, in contrast, has only short-run effects on aggregate demand, mostly through increased asset prices. Indeed, the effect of such fiscal policies is to reinforce a low-interest-rate equilibrium because the after-tax return from owning stock is higher. Yet experience with those sorts of policies over the past two decades shows they do not lead to the sorts of investments that will make the U.S. economy grow and help alleviate the downward pressure on interest rates.

Most of the policy discussion about taxes in the United States involves the negative consequences of taxing some positive outcomes, but policymakers need to remember that those positive outcomes are sometimes, in large part, the payoff on public investments. Our federal tax system is increasingly allowing those who have benefitted the most from public investments in science and technology to pay less in taxes. Simply restoring the tax system to where it was a little more than two decades ago, as proposed by Owen Zidar of Princeton University and Eric Zwick of the University of Chicago, would allow us to make the sorts of investments we need to make without deficits.

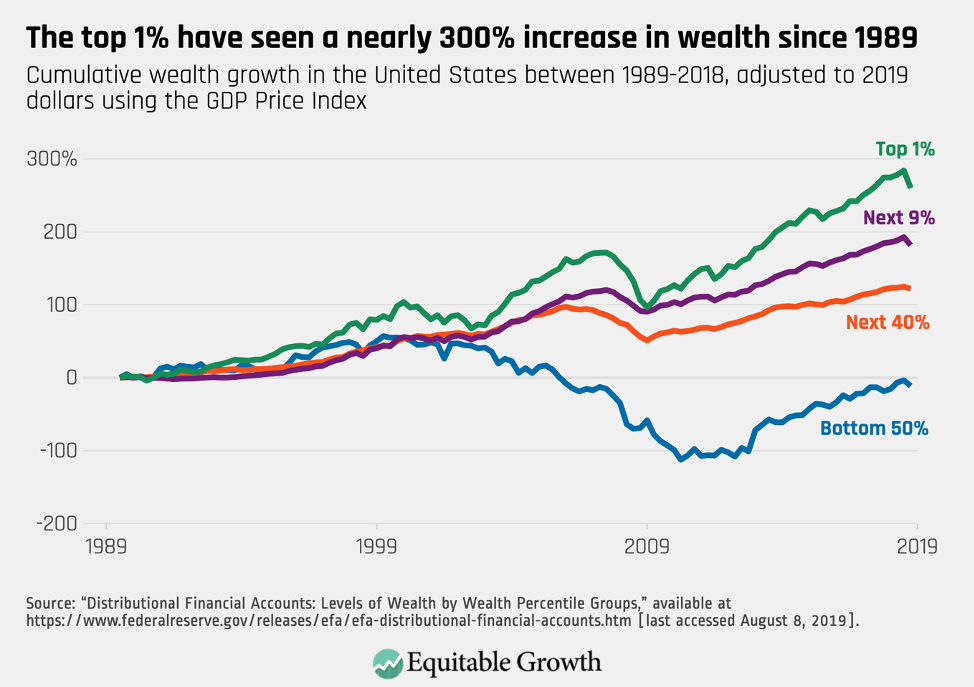

The recent history of U.S. fiscal and monetary policies suggests that bad fiscal policy and constrained monetary policy increasingly reinforced each other in recent decades. This mutual reinforcement contributed to a slowdown in overall U.S. economic growth before the coronavirus recession alongside rising income and wealth inequality and financial instability. Fiscal policymakers have abdicated their responsibility to make the investments in people, technology, and infrastructure that private investors cannot and will not make.

So, what now? When we restore the economy from the ravages caused by the coronavirus recession, we should be guided by the lessons we’ve learned in recent decades and build an economy characterized by strong, stable, and broad-based growth. If U.S. policymakers had been investing properly, for example, then right now there would be federally funded infrastructure projects in place for workers to get back to once the threat of COVID-19 diminishes. Instead, many of the infrastructure investments we might commit to now will take months or years to get underway. They’re still worth doing, but earlier investments could have supported a more speedy economic recovery now.

Today, policymakers need to focus on spending to support healthcare, maintain incomes, and keep businesses alive—and, as businesses start operating again, restore aggregate demand. But to get to the kind of strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth our nation needs, the federal government needs to invest. We need to invest in human capital—in quality childcare and early childhood education, in Kindergarten through 12th grade education, in vocational and higher education, and in programs to alleviate hunger and poverty.

We need to invest in infrastructure—in maintaining, repairing, and building our roads and bridges and mass transit systems, in enhancing the quality and security of our water systems, in preparing for and alleviating the baleful consequences of climate change, and, at long last, building rural broadband—the lack of which is freezing millions of rural Americans out of the modern economy.

And policymakers need to invest in fundamental scientific research, the lifeblood of our innovation economy and health advances. We need to invest in the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, and the other agencies supporting the basic research that has made possible everything from our smartphones to MRIs, from global positioning systems to the vaccine research we rely on today to fight the new coronavirus and COVID-19.

Tax cuts are decidedly not the answer. They double down on inequality. Most of the time, they favor the wealthy over everybody else. And the payroll tax cut now under discussion within the Trump administration and among conservative policymakers and pundits would likely just undermine Social Security finances without providing the direct infusion of funds workers and businesses need to survive the sharp economic downturn and then recover.

Although better U.S. fiscal policy is the key to better monetary policy, there are some monetary policy principles the Fed can and should embrace as it battles the coronavirus recession. Economic shocks generally involve both financial effects and real effects in the economy, with the wealthy experiencing declines in their net worth but the less wealthy experiencing job losses. In the past, the Fed has focused on propping up the financial system—for example, bailing out mortgage lenders but not mortgage borrowers during the Great Recession.

The Fed needs to expand its policy purview if the fiscal authorities won’t act in the interests of all the people. The U.S. central bank needs to make sure the next round of quantitative easing—Fed speak for the central bank’s purchase of financial securities in the marketplace to boost liquidity in the economy—or other extraordinary monetary policy action do not simply rescue the corporations whose past decisions created financial vulnerabilities.

U.S. policymakers need to enact and implement the fiscal and monetary policies tools needed to fight the coronavirus recession and prepare for a more equitable and thus more sustained economic recovery. They can and must build an economy that, unlike the one we just left behind, is built on strong, stable, and broad-based economic growth.