The essay below by Senior Policy Advisor Liz Hipple was published today by New America as part of a collection of essays in its new book, “The Emerging Millennial Wealth Gap: Divergent Trajectories, Elusive Pathways to Progress, and Implications for Social Policy.” While the income of a typical Millennial is only slightly below levels predicted by the experience of past generations, young adults in the United States today are on a lower trajectory in their wealth accumulation than their predecessors. Hipple connects this issue of the millennial wealth gap to the trend of downward intergenerational mobility, explaining how the two can interact to further exacerbate existing racial and economic inequalities as well as the consequences for the human capital development of the next generation.

A broad array of social science research—presented in this volume and elsewhere—presents a clear but troubling picture of the economic state of the Millennial generation. Young adults in America today have not achieved the same financial milestones as recent past generations. Whether measured in terms of income, assets, or net worth, Millennials are behind. If they were likely to catch up, public policy could perhaps stay agnostic. But given the combination of an economy characterized by depressed wages and shrinking benefits with a rising student debt burden, it seems more likely that their window for economic mobility is in danger of prematurely closing and public policy should respond.

The Millennial wealth gap should garner the increased attention of policymakers for a number of reasons, but especially because it is happening alongside trends of declining intergenerational mobility and rising economic inequality. These developments are interrelated and together have long-term consequences that will not only exacerbate existing racial and economic disparities but also limit the human capital development of future generations, which in turn has negative implications for future economic growth.

Recently, popular press attention has focused on the challenges Millennials face in the economy and their evolving relationship to the traditional markers of adulthood. For instance, marriage, child rearing, and homeownership rates among 25- to 34-year-olds today lag behind those of the previous generation. These are not merely the preferred reordering of life milestones established by their parents and grandparents. Rather, these are visible symptoms of the decline in intergenerational mobility, driven by the lack of financial resources among today’s young adults. Since today’s disadvantages accumulate over time and are passed down to future generations, it is essential for young families with children to be able to access economic resources to invest in their children’s development. The presence or absence of money in a household has huge implications for children’s later-in-life outcomes.

In a recent report, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?” my co-author, Elisabeth Jacobs, and I document the accumulating social science research that attests to the relationship between a family’s economic resources and a child’s subsequent outcomes. We further explore the role of parents’ economic resources in the development of children’s human capital, and how economic inequality is undermining not only the development of that potential, but also children’s ability to fully and effectively deploy that human potential, thereby depressing their future upward mobility. While the report presents a thorough analysis of research to date, our findings in each of these areas establish a strong foundation for a significant public policy response.

Intergenerational Mobility

It may be helpful to begin by reviewing recent findings about intergenerational mobility in America, as declining mobility is the backdrop against which the emerging generational wealth gap is playing out.

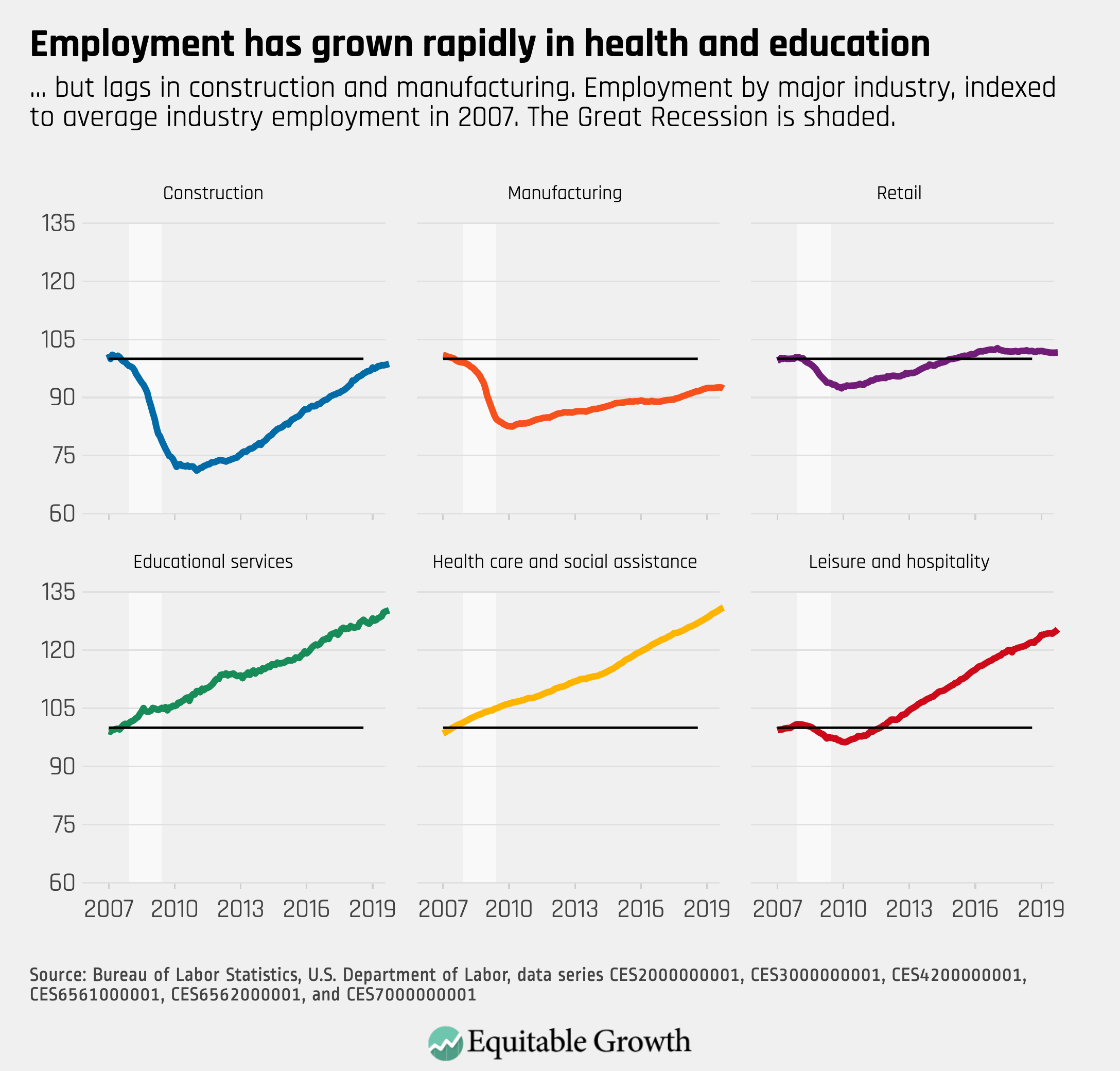

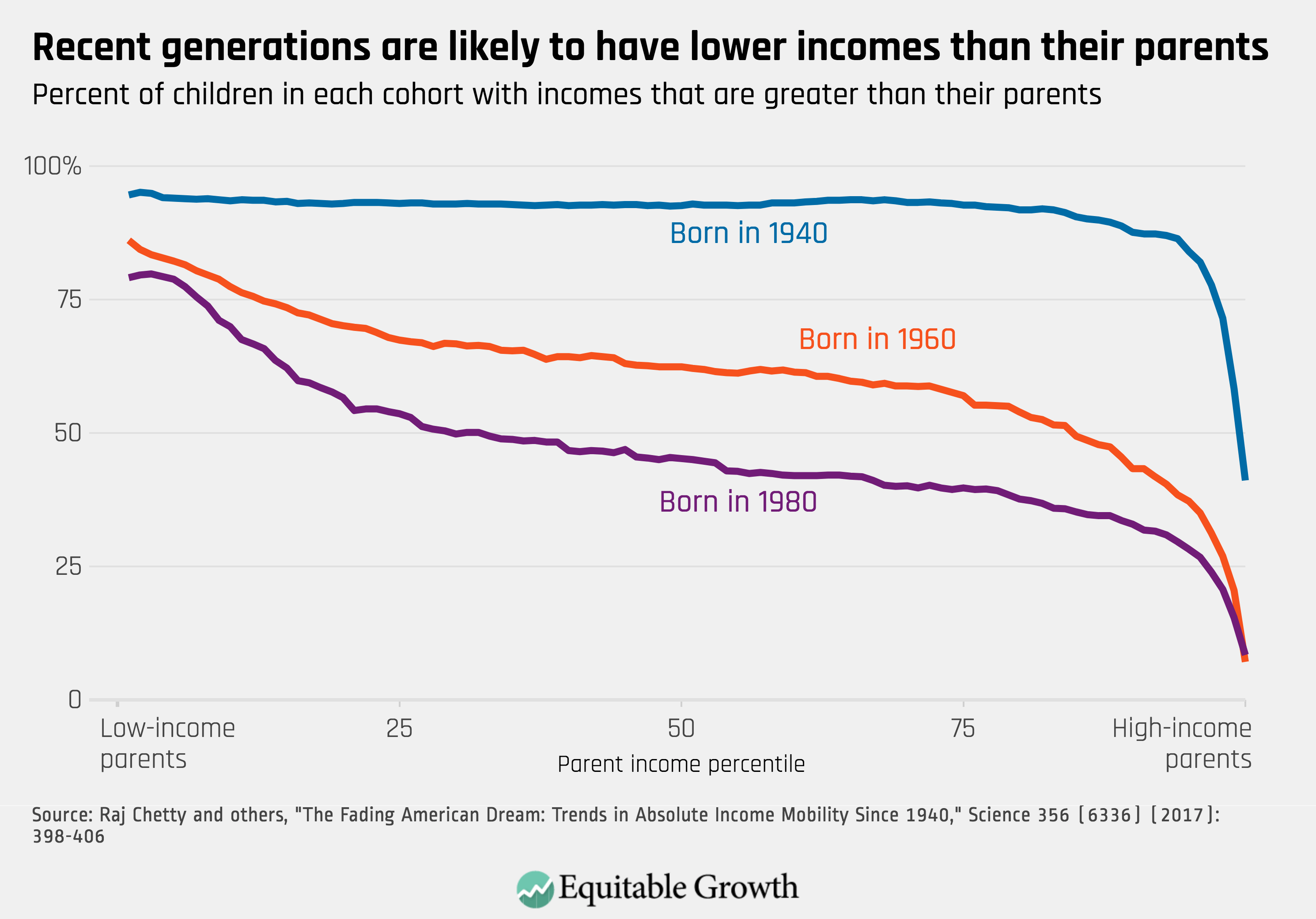

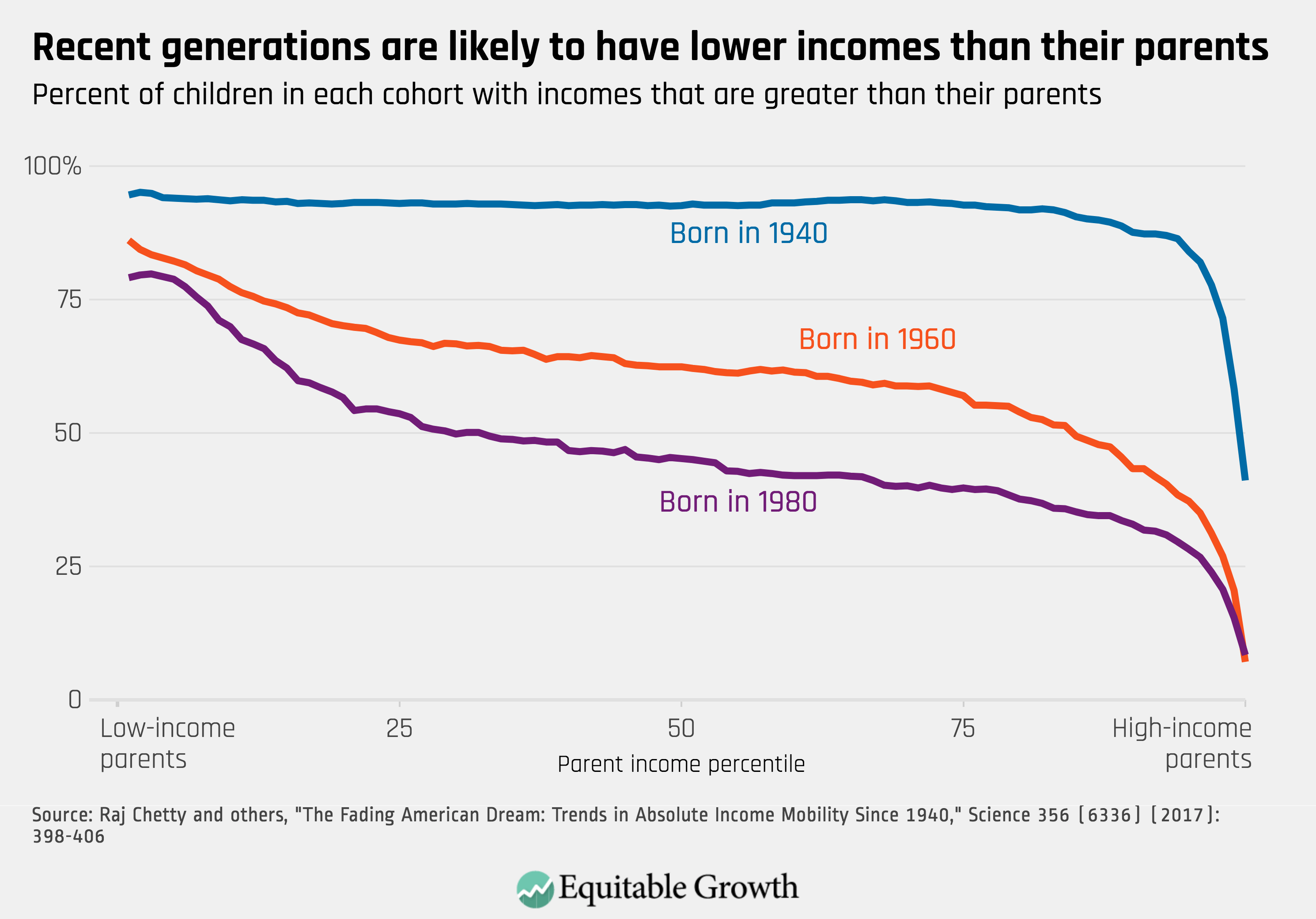

Intergenerational mobility is the relationship between a parent’s and a child’s economic position. It’s an important metric of economic well-being because it indicates whether economic outcomes reflect individual merit and hard work, or whether parental advantage (or disadvantage) dictates outcomes. It’s also a meaningful indicator of whether or not there’s been economic growth, and if that growth has been equitably distributed. If growth has been stagnant, it can tell us if any gains have accrued disproportionately to a small group. Unfortunately, recent and compelling research has found that mobility in the U.S. has been declining. While more than 90 percent of children born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents did at age 30, the same could be said at the same age for only about 50 percent of children born in 1984, according to economist Raj Chetty and his co-authors, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intergenerational Mobility.

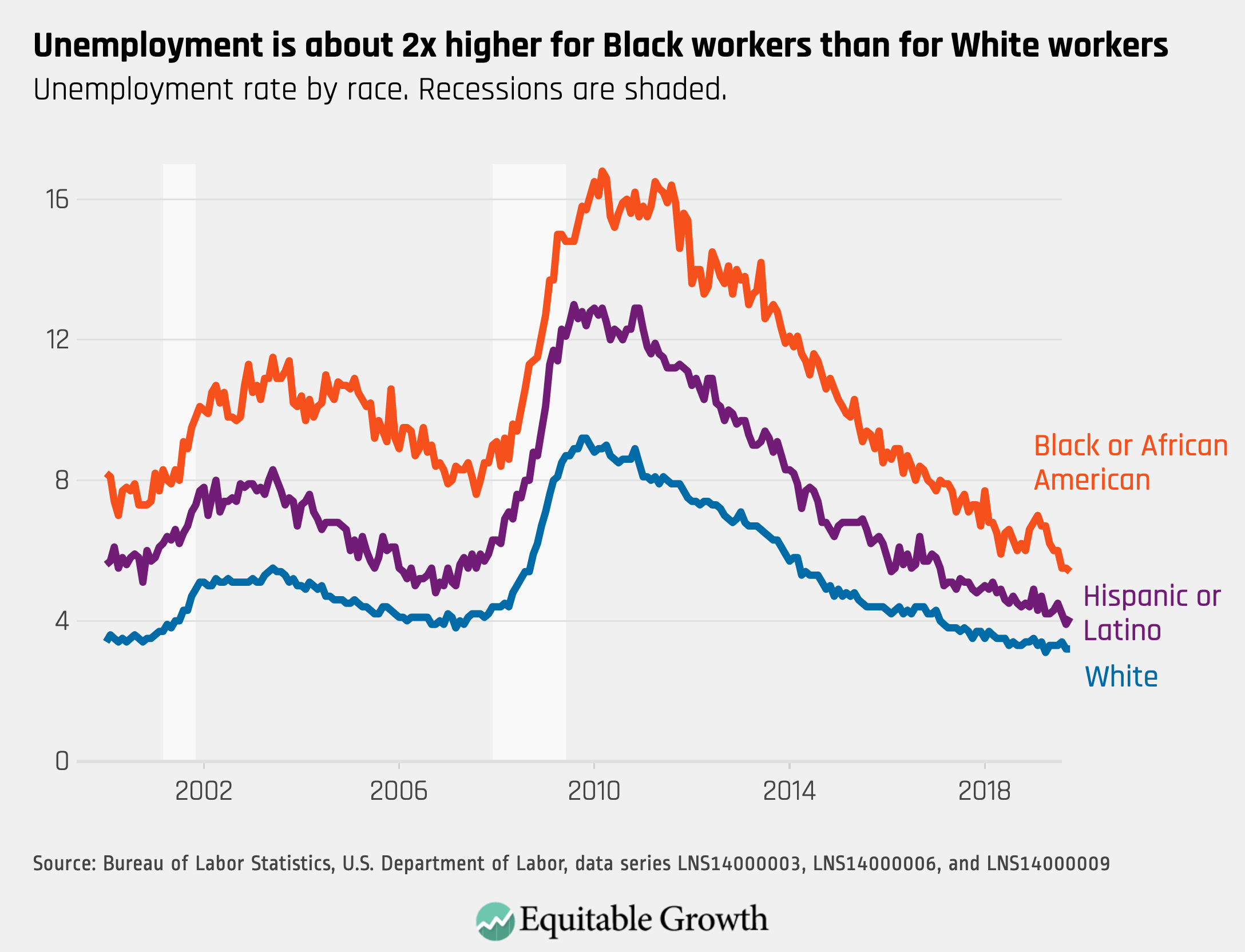

Furthermore, mobility differs significantly between different racial and ethnic groups in the United States, with black Americans in particular experiencing unusually high rates of downward mobility and low rates of upward mobility. For example, black children born into the bottom household income quintile (the lowest 20 percent ranked by income) have a 2.5 percent chance of going on to be in the top income quintile as adults, whereas white children of the same economic status have a 10.6 percent chance. And while white children born into the top income quintile are almost five times as likely to still be in the top income quintile as adults as they are to fall to the bottom, black children born to parents in the top income quintile are just as likely to fall to the very bottom as they are to stay at the top.

Despite the prevalence of explanations for these differences that emphasize factors that supposedly represent individual choices or hard work—such as marriage patterns or educational attainment—Chetty and his co-authors find that differences in family characteristics, including wealth, explain very little of this gap in intergenerational mobility for black and white Americans. In other words, all else equal, these findings of mobility outcomes indicate that racial discrimination clearly plays a role in explaining why these differences persist.

In our full paper, Jacobs and I explore more of the facts and statistics on intergenerational mobility in the United States, including how it has changed over time and manifests in different places and geographies. For the purposes of this discussion, though, the key takeaways to keep in mind are that the decline in mobility from the 1940 to the 1980 cohort means that young adults today are entering adulthood with lower earnings than previous generations. Consequently, they have less to save from. Additionally, the opportunity to save and build wealth in America is distributed differentially depending on your race and ethnicity. This should be the context for any policy discussion of the Millennial wealth gap.

Economic Inequality and Wealth Gaps Limits the Development and the Deployment of Human Potential

A large body of research indicates that in the U.S. the extent of economic resources at a family’s disposal impacts their children’s economic outcomes later in life. To give just one example, research has found that even just $1,000 in additional income from the EITC increases a host of positive indicators, including higher reading and math scores; increased probability of high school graduation, college completion, and employment; and increased earnings. While this example uses income, rather than wealth, as the measured financial resource, it demonstrates the importance of financial resources today on outcomes tomorrow.

To understand the connection between parental economic resources and children’s adult outcomes—and how economic inequality could be intermediating that relationship—Jacobs and I developed a framework for making sense of the channels linking the two concepts. One of those channels is the development of human potential. On a fundamental level, every individual is born with a certain amount of human potential, but the opportunity to develop that potential to its fullest varies dramatically based on the circumstances of family, community, institutional factors, and myriad other structural constraints. These inequalities of opportunity are often compounded across multiple realms, with major lines of research demonstrating the links between inequality and access to health, parental investments of time and money in their children, and the quality of early childhood education, as well primary and secondary schooling—all of which are critical pathways for the development of the human potential necessary for upward mobility.

As families have fewer resources to invest in their children today, the consequences of the Millennial wealth gap will extend into the generations of tomorrow. This dynamic has already been apparent in the relationship between wealth, educational opportunities, and the realization of long-term human potential. A case in point is the unfortunate reality that in the United States, buying a home in a “good” school district is often the single biggest way a parent invests in their child’s human capital development. In this process, it is wealth, rather than income, that is the means through which the home is purchased, making it especially consequential in determining the future outcomes of the next generation.

This dynamic reflects how the Millennial wealth gap risks exacerbating existing economic and racial inequalities. If, as explained in the chapter by William Emmons, Ana Kent, and Lowell Ricketts, Millennials have lower than expected wealth by a certain age, then it will be more difficult to self-finance a first home purchase. Those who can tap down payment assistance from their parents are at a distinct advantage. Winning the birth lottery takes on a whole new significance, as only those lucky enough to be born into families with enough wealth to be able to pass it along can get their own start in the wealth accumulation process.

It also means that policies that have historically and systemically blocked black Americans from building wealth continue to have consequences that reverberate today for black Millennials. For example, federal redlining denied black Americans access to traditional mortgages and therefore forced them into contract buying, which did not build equity. This means that racist policies that prevented the purchase of a house by grandparents or parents 50 years ago continue to have an impact. Not only is there less wealth to transfer directly, there is less wealth to invest in their children’s human capital development, whether it is through supporting education or jump-starting wealth building through the purchase of a home. Indeed, while 34 percent of white adult children receive financial support from their parents for higher education and 12 percent for homeownership, the same is true for only 14 percent and 2 percent of black adult children, respectively. Discrimination in the past, reflected in the racial wealth gap, continues to reverberate today and into the future.

But even if there were true equality of opportunity to fully develop one’s human potential, the development of human potential is insufficient on its own if individuals are not able to fully deploy their talents. And family economic resources—particularly wealth—also play a vital role in young adults’ ability to fully deploy their potential. For example, in addition to the relevance of parental resources for attendance and completion of postsecondary education, wealth can shape how an individual is able to get the most out of a college education and make use of that investment. Family wealth may provide an insurance function, allowing those with greater access to the cushion of family assets (and the absence of debt) to take risks that ultimately pay off with greater rewards. As sociologists Fabian Pfeffer of the University of Michigan and Martin Hällsten of Stockholm University explain:

[C]hildren who are able to fall back on their parents’ wealth when, for example, they drop out of college or experience a prolonged school-to-work transition period, or have early episodes of unemployment, are more likely to opt for long-term human capital investments, such as college attendance, or choose particularly competitive or protracted career paths that they may be able to sustain even in the face of early set-backs.

These findings show that wealth may shape the behavioral choices of the next generation, thereby shaping opportunity by providing some with a soft cushion for a slip down the economic ladder and others with no cushion at all. Indeed, economist Greg Kaplan finds that the ability to live with one’s parents allows young people to search longer for jobs that have better prospects for future earnings growth, increasing their chances of upward mobility and of successfully beginning to build wealth of their own.

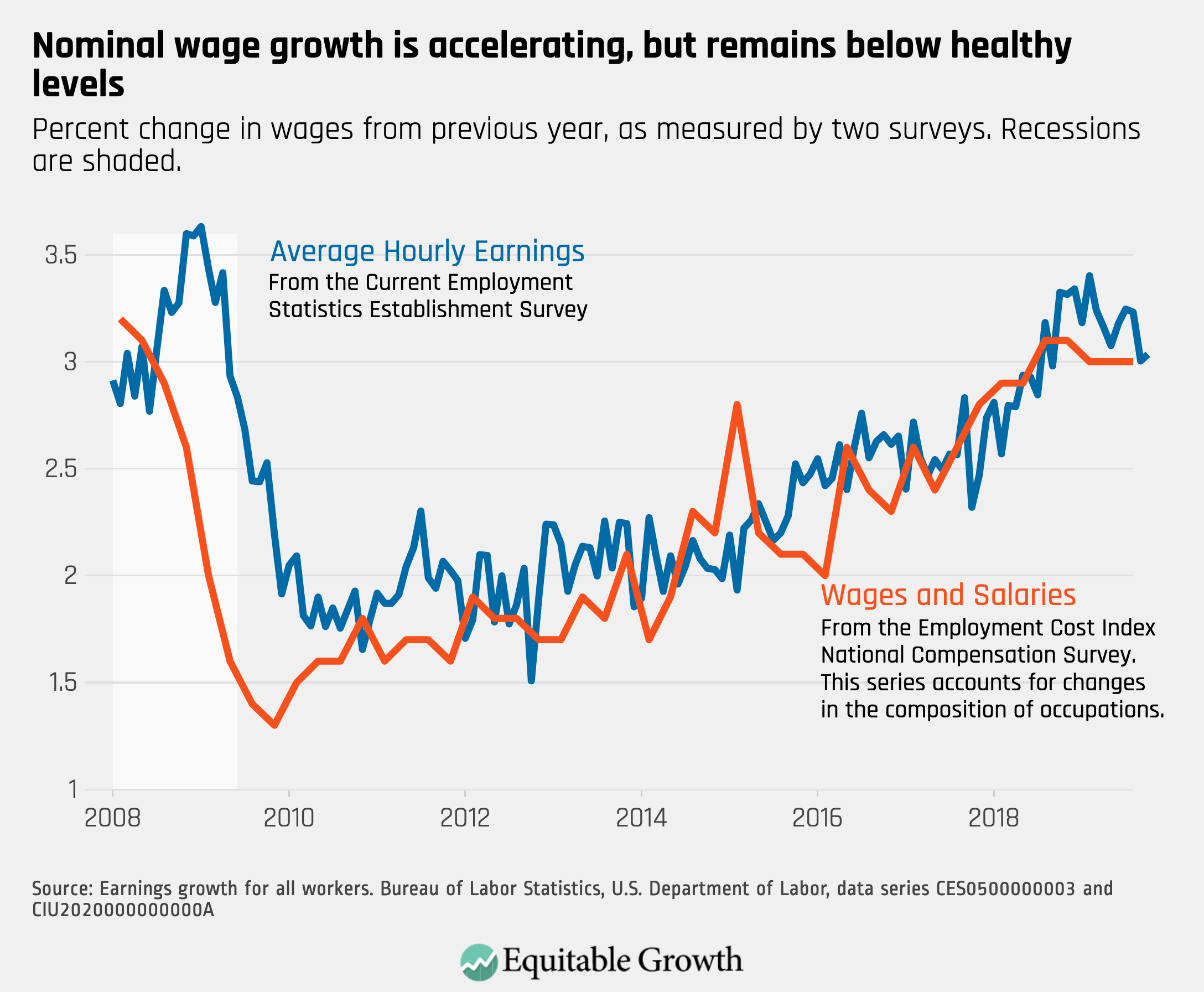

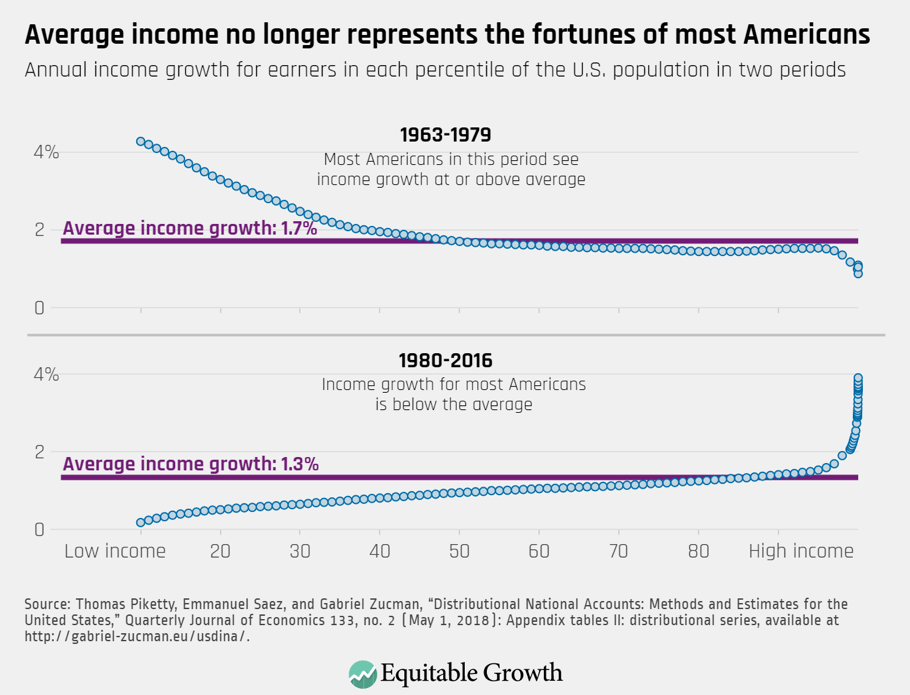

Another roadblock to Millennials’ ability to fully deploy their human potential is the structural changes in the labor market over the past 30 years, which have depressed wages and thereby delayed wealth building. For example, young adults who replicate their parents’ educational and occupational backgrounds and end up in the same type of work and in the same relative place in the economic distribution earn less in inflation-adjusted terms than their parents did a generation ago. There are a number of reasons for these changes, including the fissuring of the workplace and the decline in job ladders, which we consider in depth elsewhere. What is relevant here is that these structural changes, coupled with the fact that Millennials entered the labor market during the Great Recession, threaten to cause long-term and persistent negative effects for Millennials’ earning potential, which will further weaken their ability to build wealth down the road.

Policy Implications

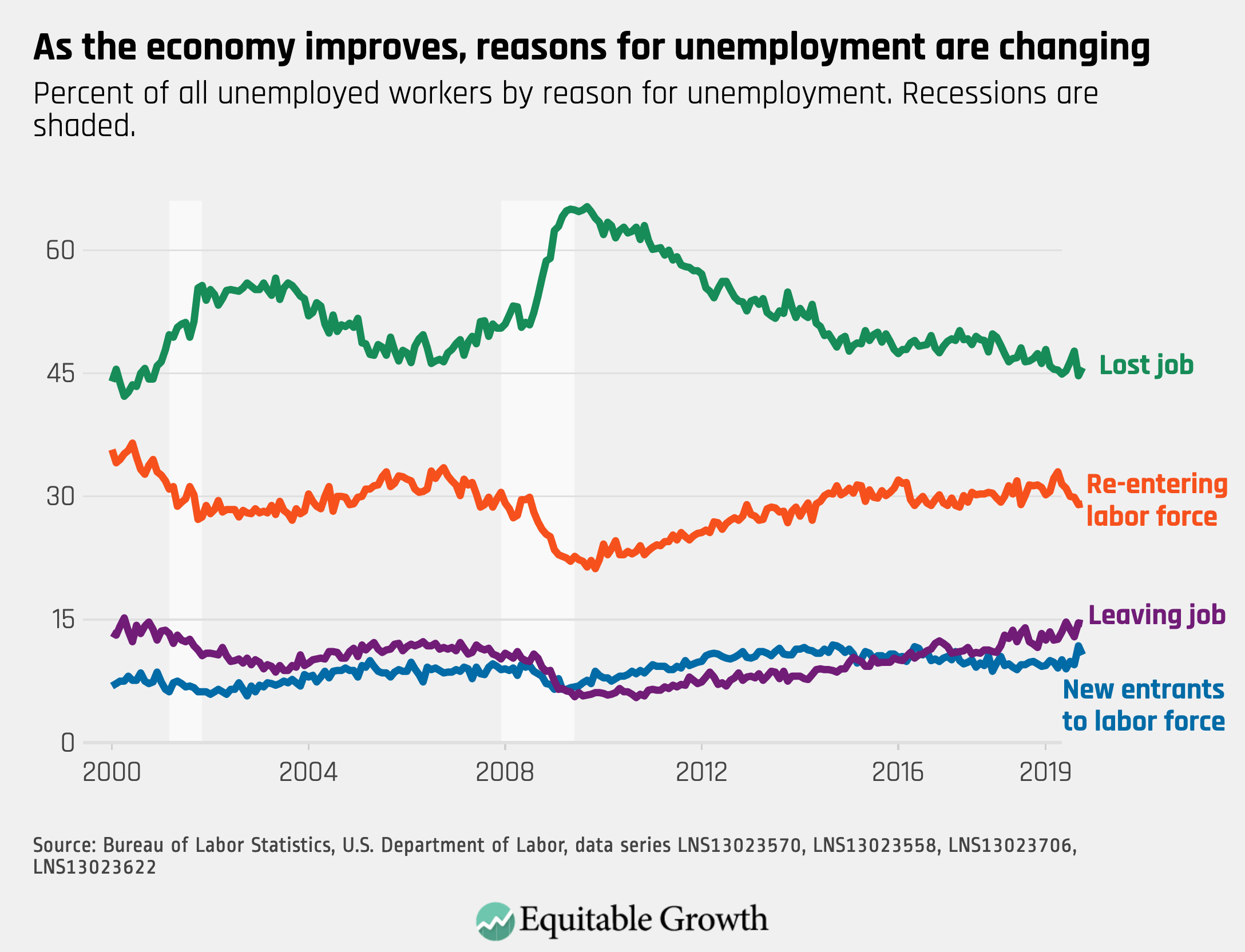

Policymakers need to take these structural changes into account—and acknowledge this history of discrimination—as they craft future public policies to promote wealth building. Traditionally, the pillars of wealth building in America have been grounded in being able to access education, skills, and training; secure steady employment; increase ownership of assets over time; and receive family gifts, transfers, and inheritances. We’ve seen how these pathways are not open to everyone, and how the current cohort of young adults is faring poorly. For Millennials, education and skills have increased, but steady employment has gotten more precarious, especially for those who graduated into the Great Recession, which limits the income with which to increase ownership of assets over time. This leaves the fourth pillar—the receipt of family transfers—to take on a larger and increasingly disproportionate role in future wealth accumulation.

It is a problem for our democracy and our economy if family wealth determines long-term child outcomes. If the cushion of family assets (and the absence of debt) allows young adults to disproportionately take risks that can ultimately pay off with greater rewards, then those without such assets are needlessly disadvantaged. This creates a feedback mechanism in which privilege begets privilege. To prevent such a scenario from gaining momentum, policymakers must work to level the playing field. In doing so, they should push beyond solutions that emphasize merely equalizing access to activities that support human capital development, such as education and skills attainment. As we have seen, the development of human potential is insufficient on its own to address the forces depressing economic mobility and opportunities for wealth accumulation. Rather, policymakers must grapple with ways to remove the roadblocks young adults face when they seek to deploy their potential in the economy.

A forward-looking policy agenda should be grounded in a recognition that the structure of the U.S. labor market has changed in ways that fundamentally thwart upward mobility. Wage stagnation, fissuring of the workplace, and a decline in job ladders depress workers’ earning power. Discrimination, particularly racial discrimination, persists in ways that run afoul of basic principles of equity, disempowering some workers and advantaging others. Growing inequalities in household balance sheets shape behavior and risk preferences, allowing those born into wealth to accumulate additional advantages over a lifetime while those who enter the labor market further down the economic ladder face limited pathways upward.

None of these dynamics are inherently natural. Many have the potential to be fundamentally reshaped by policy. Familial advantage—or disadvantage—can be passed along to children in multiple ways. While this might seem daunting to policymakers contemplating solutions, it also means that there are multiple angles from which to tackle the problem. There will be no silver bullet or quick fixes, but the emerging Millennial wealth gap is too large to ignore. Instead, there should be a concerted effort to develop and implement policies to ensure that access to opportunity is truly equitable. Our collective goal should be to ensure that all members of our society are able to fully deploy their potential. To do so requires that wealth is not passed along mechanically from generation to generation, but that our collective resources support an economy where the human capital, innovation, and dynamic economic growth are unleashed rather than left by the wayside.