Weekend reading: “ Increasing public investment” edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

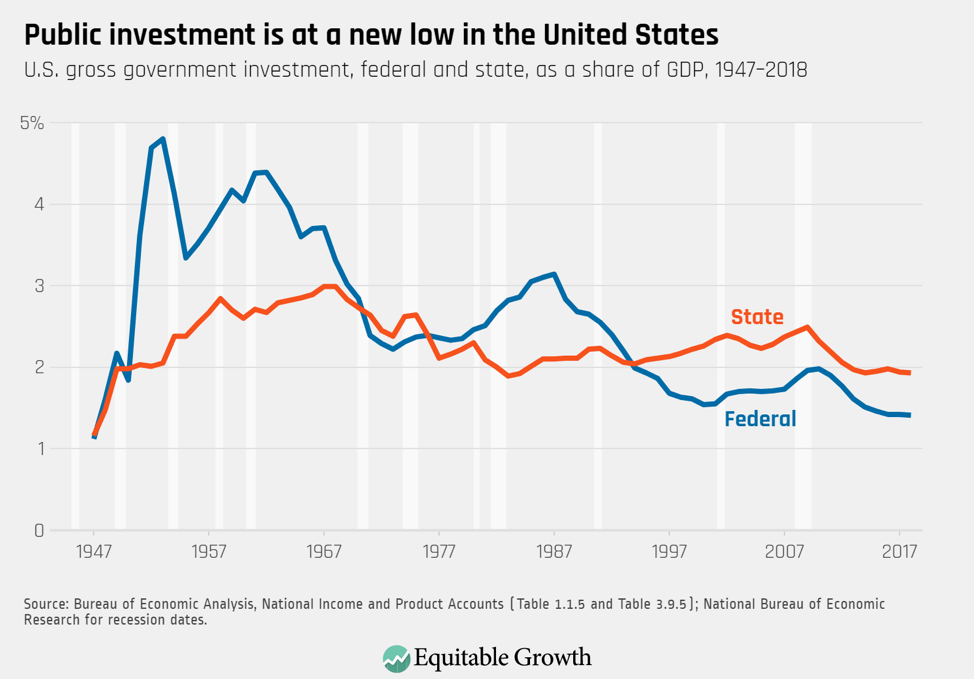

The evidence is clear: Public investment is an essential driver of productivity and economic growth. Sadly, the evidence also is clear that levels of U.S. public investment have now dropped to a point not seen in decades, at a time when it is most critical due to rapidly growing economic inequality. Policymakers can reverse this trend via two key pathways—investments in infrastructure and human capital—in order to boost private-sector spending in these areas as well, writes Somin Park. And, Park continues, given the current low interest-rate environment, the U.S. government should capitalize on this moment to deliver higher growth and lower inequality for everyone.

Is competition or a monopoly better at spurring innovation? The age-old question gets an answer—at least, in terms of the pharmaceutical industry—in a new working paper that looks at so-called killer acquisitions, in which an incumbent firm acquires a potentially competitive product while it’s in development and subsequently terminates the development of that product. This consolidation is probably stifling innovation, rather than boosting it, writes Raksha Kopparam in a blog post describing the working paper and its findings. Because killer acquisitions typically occur when the incumbent drug-maker has significant market power, the acquisitions are likely to prevent innovation and competition in the very markets where a new drug would have the most impact. Enforcers should be aware of this as they review these types of transactions, Kopparam concludes, to help patients access new and better products at lower costs.

Links from around the web

With Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) this week releasing his plan for taxing wealth, the idea of increasing taxes on the richest Americans appears to be catching on with candidates for the Democratic presidential nomination. Though Sen. Sanders’ proposal, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s (D-MA) before it, would face major political hurdles prior to a potential enactment, “these proposals represent the broadest rethinking of tax policy in decades,” write Nelson D. Schwartz and Guilbert Gates in The New York Times. But, they ask, how would the ideas with the most traction at the moment—implementing a wealth tax, raising the marginal tax rate, increasing the estate tax, and rethinking the capital gains tax—actually work?

Earlier this week, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) unveiled a package of bills aimed at cutting poverty in the United States by expanding access to federal benefits and updating the federal poverty line to include expenses such as childcare and internet access, as well as adjusting the poverty limit based on a person’s location. “If we can acknowledge how many Americans are actually in poverty, I think that we can start to address some of the more systemic issues in our economy,” Rep. Ocasio-Cortez told NPR’s Steve Inskeep this week. For the record, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates that approximately 40 million Americans live in poverty, including more than 13 million children.

The federal family and medical leave system in the United States has not changed since President Bill Clinton signed the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993—more than 26 years ago—and that law leaves much to be desired, writes Daria Dawson for Essence. For one thing, it only provides 12 weeks of unpaid leave to a very restricted group of workers. “Paid leave is not just a women’s issue. Nor just a white women’s issue. Nor just a family issue. It is a healthcare issue. It is an economic issue,” and, she continues, “paid leave is an issue that voters care very deeply about.” So, why is it that only 15 percent of American workers have access to a paid family leave program through their employers? As Dawson concludes, it’s time to give federal family and medical leave a 21st century makeover.

Under current law, the secretary of Health and Human Services is unable to negotiate directly on the costs of prescription drugs covered by Medicare, which leads to higher drug costs for patients because private insurers don’t have the same leverage that the federal government does in these negotiations. But a new bill proposed by House Democrats seeks to change this practice for up to 250 of the most expensive drugs without generic or biosimilar competition while also penalizing companies that refuse to negotiate with HHS. The bill comes amid increasing bipartisan momentum on the topic of prescription drug regulation, reports Li Zhou for Vox, largely due to voter pressure on lawmakers to act.

Noncompete agreements hinder millions of U.S. workers from accessing better jobs and lower the wages of these workers by reducing competition. A handful of states have banned noncompete agreements, including Oregon, which passed a law in 2008 to prevent the practice across the board—and a recent study shows that wages for workers no longer bound by noncompete clauses increased by as much as 21 percent as a result. “Put plainly,” writes The New York Times Editorial Board in a piece lamenting the broad use of noncompetes, “the old rule allowed employers to suppress their workers’ pay.”

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Public investment is crucial to strengthening U.S. economic growth and tackling inequality,” by Somin Park.