The national debate on economic policy recently turned along generational lines, with the popularization of the sarcastic phrase “OK, Boomer.” The premise is that prototypical baby boomers are misguided in their critique of structural economic policies that many millennials argue would create a U.S. economy where gains of growth are shared by a broader swath of people.

The reasons for this generational division may be borne out by the evidence. New research from Kevin Rinz of the U.S. Census Bureau follows the employment and earnings trajectories of workers before, during, and after the Great Recession of 2007—2009. Rinz finds that younger workers in the millennial generation lost out on the gains of the economic recovery since 2009 while workers in other age groups largely recovered.

These variations are due to structural factors in the U.S. economy that contribute to lower earnings, such as interfirm wage inequality and increasing employer concentration, as well as the impact of economic downturns on individuals’ investments in human capital. Bearing the brunt of these trends is sparking these younger millennial workers to call for structural changes that would alter the negative consequences of economic inequality that they face.

As Rinz notes in his new Equitable Growth working paper, much of the analysis of the labor market effects of the Great Recession are focused on workers who were in their prime working years, commonly ages 25 to 44 (across generations prior to the boomers) and who have the strongest labor force attachment, particularly men. But the question remains for younger workers, most of whom were not yet in their prime working years when the recession began: How does exposure to an economic downturn affect workers as they make decisions about investing in their own human capital through higher education and begin their careers in the labor market?

To investigate this, Rinz follows a modified approach of research by Equitable Growth grantee Danny Yagan at the University of California, Berkeley by estimating the employment and earnings effects by generational cohort on individuals resulting from local unemployment shocks between 2007 and 2009. Using a 2 percent sample of the 2018 Census Numident file linked to W-2 earnings data from 2005 to 2017, Rinz is able to connect self-identified key features of individuals, such as their birth year and other demographic data, to administrative data on their employment and earnings histories. He then estimates the impact of unemployment shocks in different commuting zones, following the method used in Yagan’s research, on both employment and earnings in the years following.

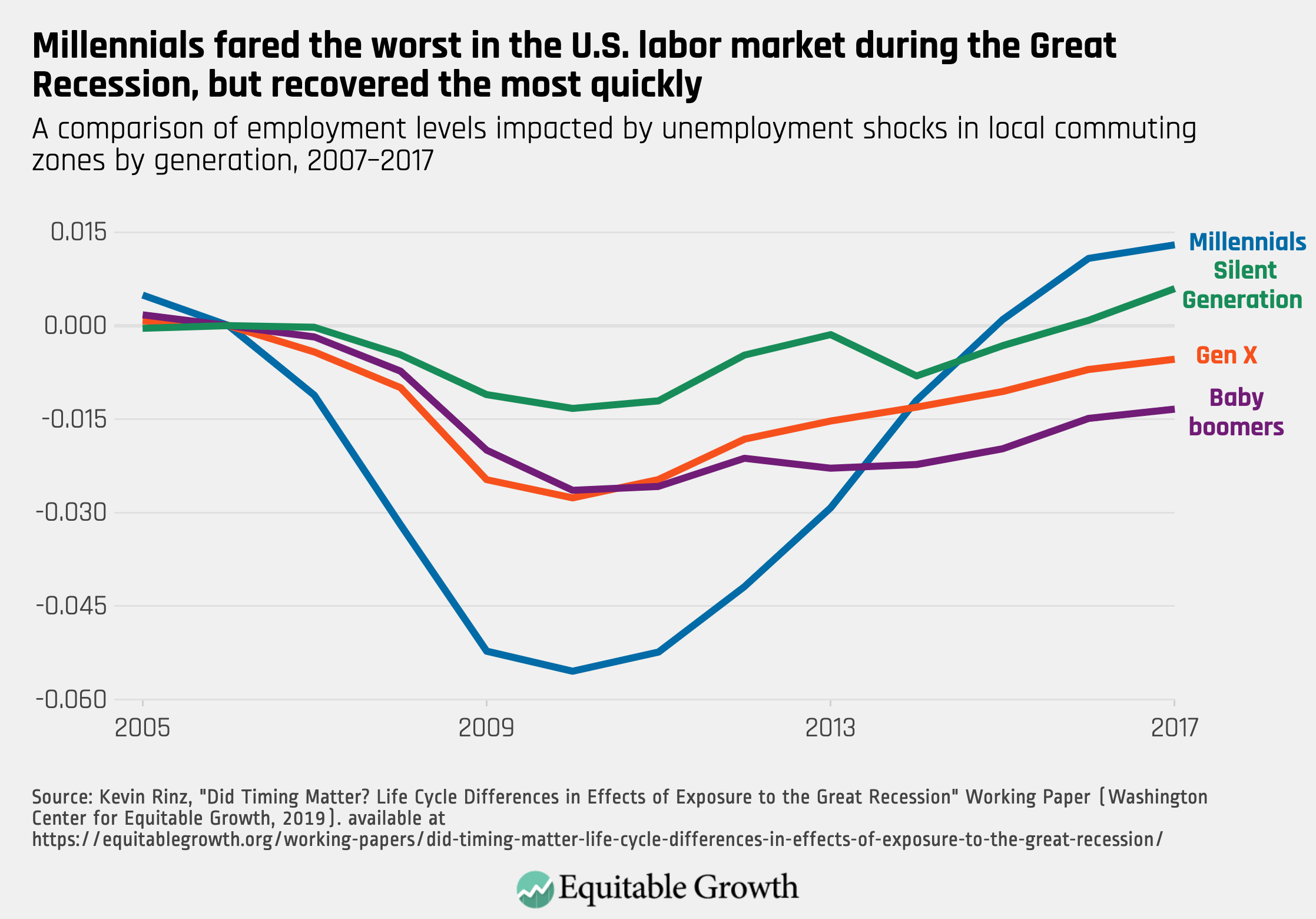

Rinz finds that average local unemployment shocks had a negative impact on the employment of all age cohorts, but that millennials (born in 1980—1994) were the most negatively affected, with the greatest decline in employment compared to Generation X (1965—1979), baby boomers (1944—1964), and the Silent Generation (1928—1945). Rinz also finds that millennials’ employment levels recovered more quickly than the other generations. Interestingly, millennials who were exposed to greater unemployment shocks during the Great Recession were actually more likely to be employed by 2017, compared to millennials exposed to smaller unemployment shocks. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

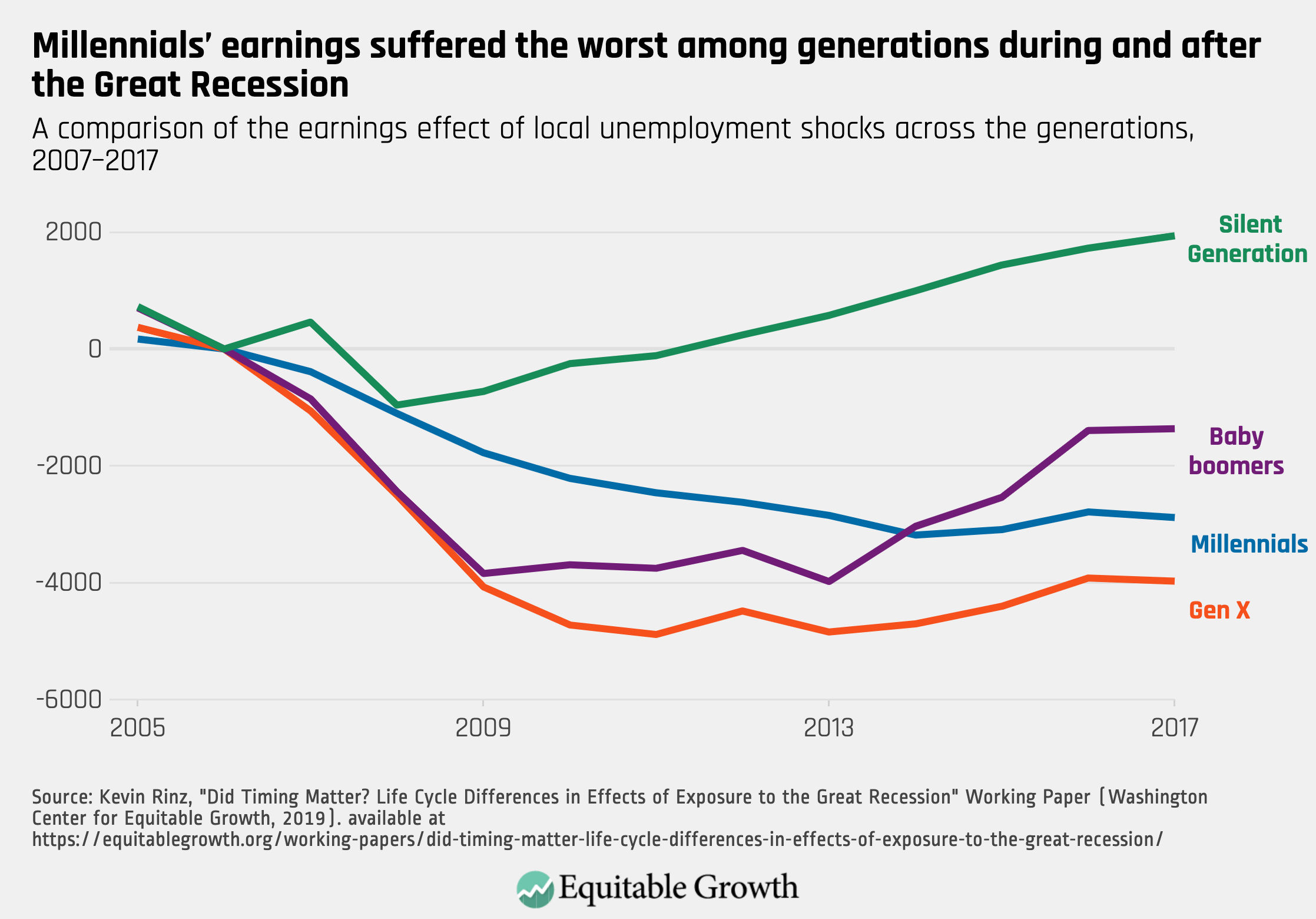

So, millennials’ employment opportunities recovered, but their earnings did not. Rinz finds that the average loss of earnings due to exposure to a local unemployment shock stabilized around $3,000 for all workers. But he also finds that from 2007 to 2017, millennials with more exposure to unemployment shocks lost 13 percent in cumulative earnings, compared to 9 percent for Generation X and 7 percent for baby boomers. Baby boomers also experienced more significant earnings recovery, with their earnings losses shrinking 65 percent by 2010. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

To investigate the reasons for these continued losses, Rinz examines the impact of education decisions, employer match (economic parlance for workers matching into jobs for which they are best suited), and labor market concentration. He finds that exposure to an economic downturn can have an ambiguous effect on education decisions by reducing the opportunity cost of leaving the labor force to pursue education but also reducing the resources available to invest in education.

Rinz finds that millennials in areas with unemployment shocks completed less education. If local labor market conditions forced millennials to leave school and take whatever job they could get, this would depress their earnings in the long run. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

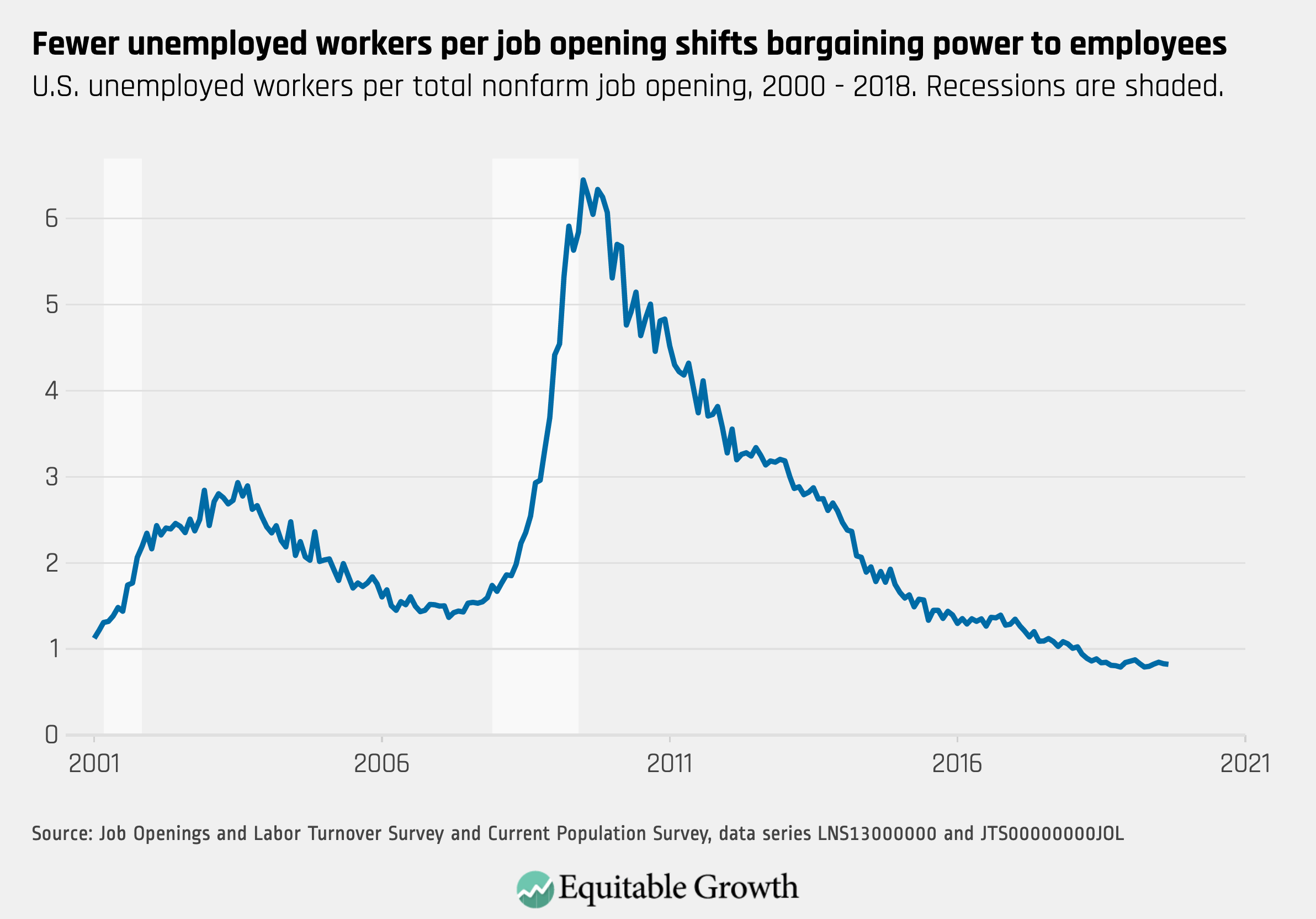

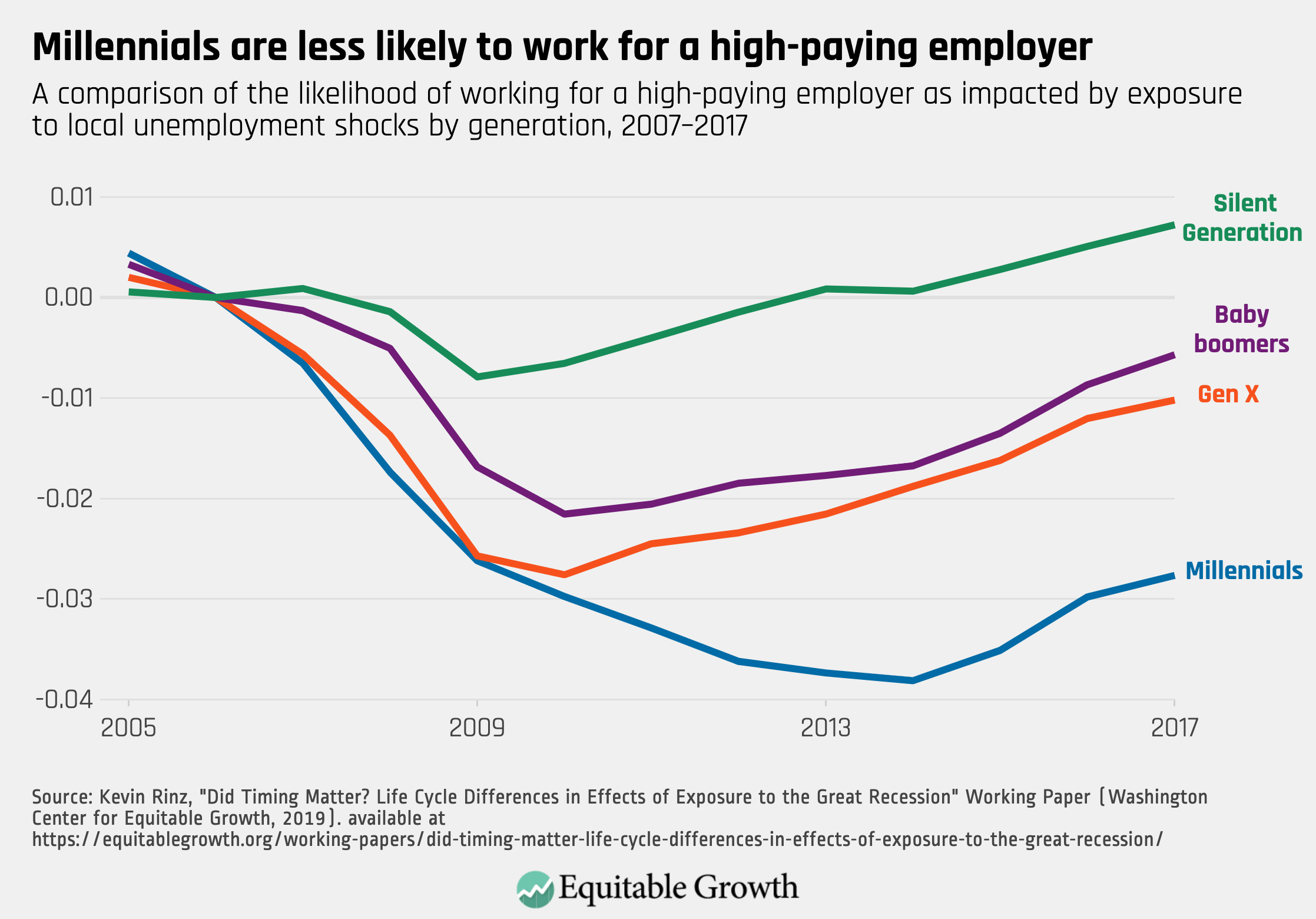

Rinz also finds that exposure to a local unemployment shock persistently made millennials less likely to work for high-paying employers into the future. Being part of a large reserve of individuals looking for work may reduce these workers’ bargaining power for commanding higher wages in the future, even once they are back at work, because millennials exposed to unemployment shocks had larger employment declines. On top of this, Rinz finds in his previous research that the impact of local labor market concentration has reduced the earnings for millennials, although this effect is smaller in magnitude than the impact of unemployment shocks.

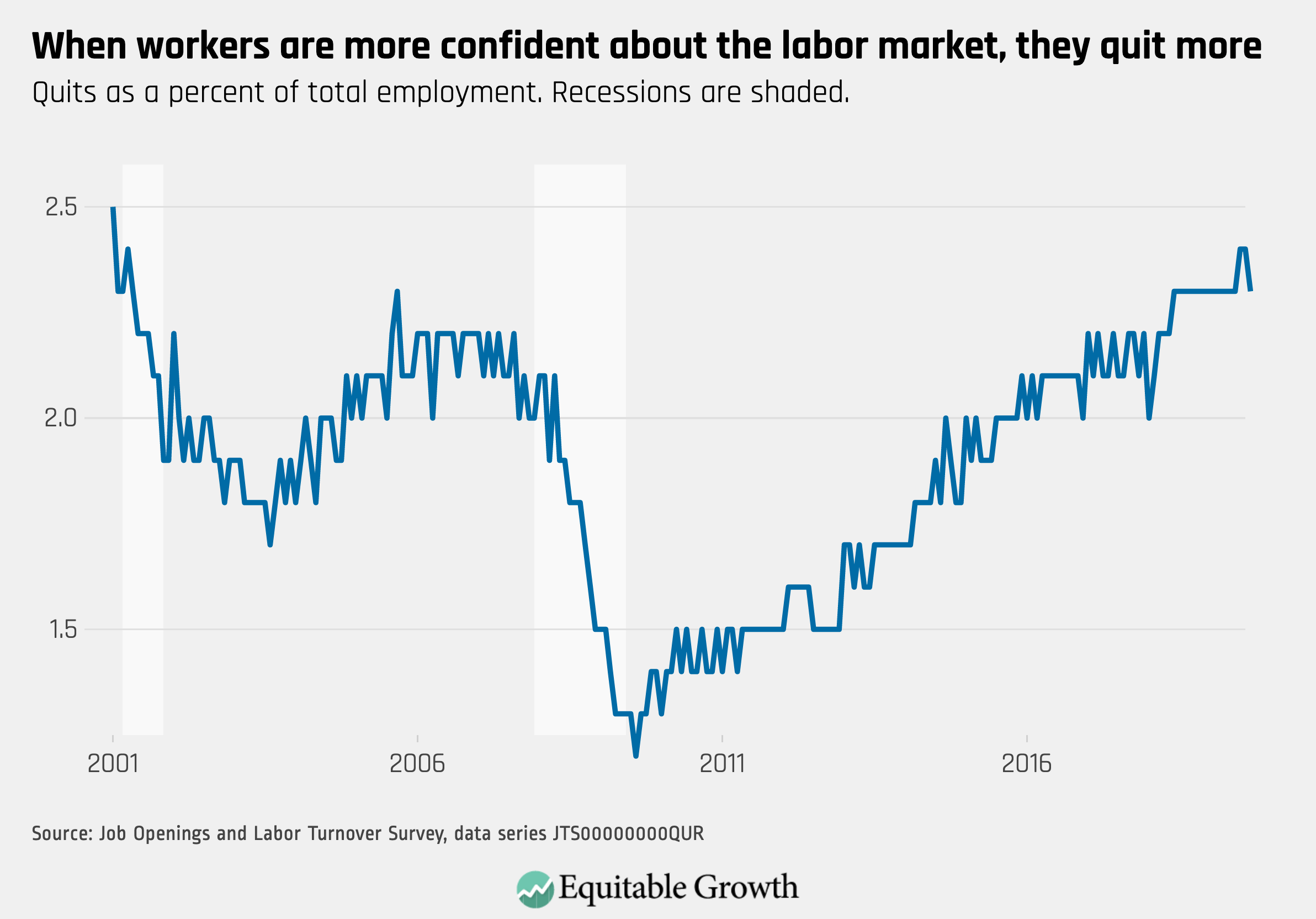

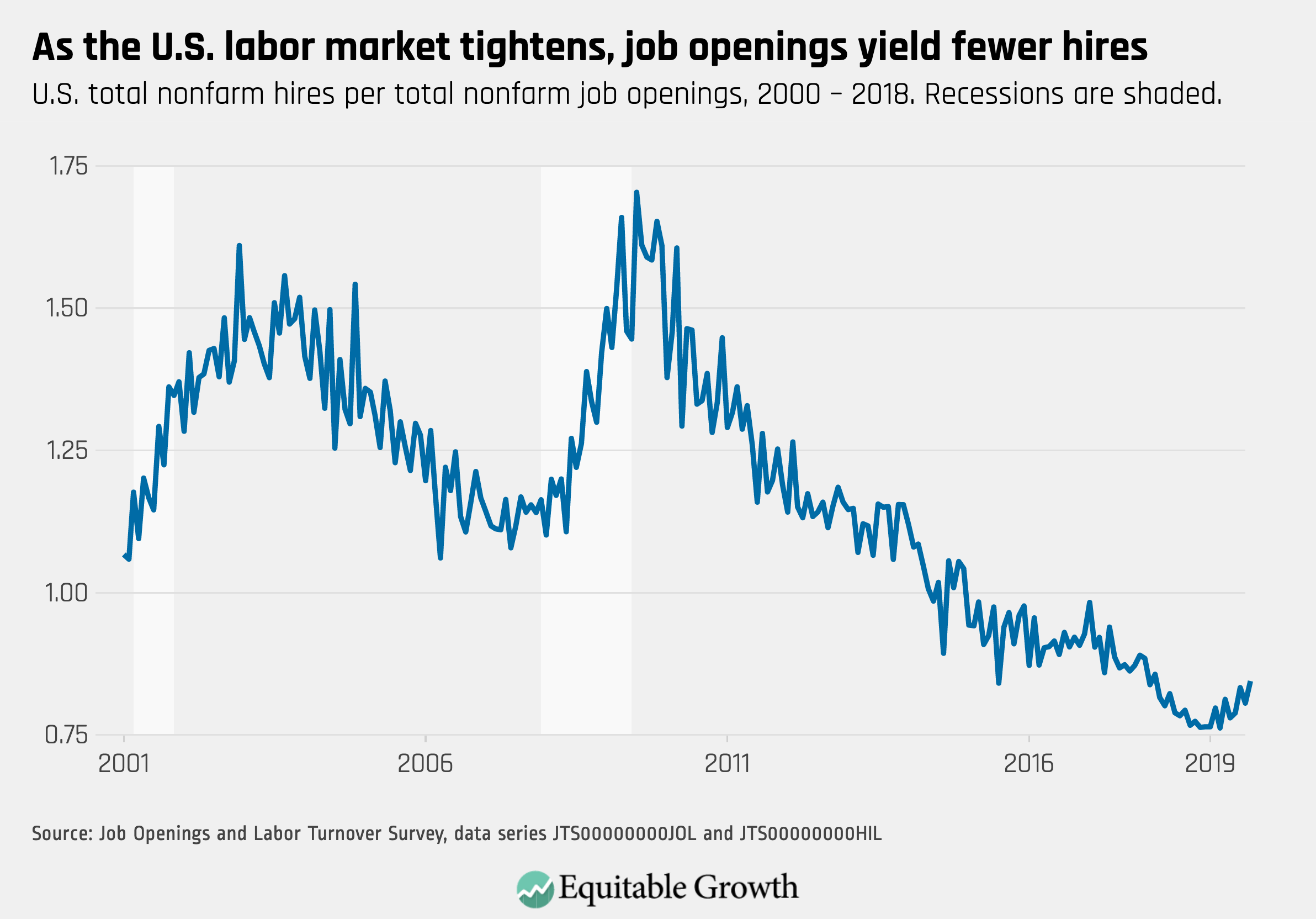

Persistent negative outcomes for younger workers demonstrate how inequality reduces economic opportunity for those who have less to start with in terms of jobs and earnings. This demonstrates how the competitive forces of a tight labor market—as measured by low overall unemployment during the now 10-year economic recovery since the end of the Great Recession—does not necessarily translate into better opportunities for all workers, such as higher wages for younger workers.

No wonder millennials, whose economic well-being continued to suffer after the Great Recession, roll their eyes when older generations, who lost less of their long-term earnings, claim that structural change is not necessary. These younger workers intuitively understand that structural change may be the only thing that allows for more broadly shared economic growth.