Overview

“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other academics to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

In this installment, Equitable Growth President and CEO Heather Boushey talks with Gabriel Zucman, professor in the Economics Department at the University of California, Berkeley. His research focuses on global wealth, inequality, and tax havens. Zucman also is co-director of the World Inequality Database, a database aiming at the provision of access to extensive data series on the world distribution of income and wealth.

In an in-depth conversation about his research and its implications for public policymaking, Boushey and Zucman discuss:

- The creation of distributional national accounts

- The importance of distributional national accounts

- The significance of rising income inequality in the United States

- How income inequality in the United States compares to other countries

- What new research needs to be done on measuring economic inequality

Heather Boushey: Gabriel, it’s lovely to see you. Thank you. I’m glad to have you in Washington here today.

Gabriel Zucman: Thanks for having me.

Creating distributional national accounts

Boushey: I want to ask you a few questions about your research. The first is about the development of what you all call distributional national accounts, which is a bit of a mouthful. First of all, explain to me how distributional national accounts help economists and policymakers learn about inequality in the United States and worldwide.

Zucman: There are two different conversations going on today. One is about macroeconomic growth, which relies on national accounts data: macroeconomic statistics of [Gross Domestic Product] growth, investment, consumption, etc. This is what macroeconomists talk about. Then you have a second conversation, which is about inequality. In academia, when scholars study inequality, they use tax data and survey data. The problem is that there is a big disconnect between what you see in tax and survey data and what you see in the national accounts data. As a result, there is a disconnect between these two conversations.

Generally, we either talk about growth or about inequality, but rarely about the two together. The distributional national accounts we’re constructing are an attempt at bridging the gap between macroeconomics, on the one hand, and inequality studies on the other hand. The way we try to do that is by distributing the totality of national income—a comprehensive measure of income that is very close to GDP. To have a comprehensive view of how all of GDP (or all of national income) is distributed in the United States, we combine survey data and tax data in a systematic way.

Boushey: And when you say income, you mean corporate and personal income?

Zucman: I mean total national income, which is GDP minus capital depreciation plus the net income that the United States receives from the rest of the world. That’s what I call income, and that’s our main focus.

What we want to do is simple. Whenever we learn that national income or GDP grows 2 percent a year, we want to be able to say what this means for each group of the population. At what rate is income growing for, say, the bottom 50 percent of the distribution, the middle 40 percent—which you could call the middle class—the top 10 percent, and the top 1 percent?

Of course, it’s not possible for incomes to grow for each group of the population more than GDP. Yet oftentimes, you see reports where that is being shown. Our goal in this project is to make sure that things add up—that income growth across the income pyramid adds up to national income growth. That’s the main goal, and it’s important because it yields new insights about what’s happening to inequality in the United States. For example, we can have a better sense now of the relative role played by labor income and capital income in the evolution of income inequality in the United States.

Up to the late 1990s, inequality was rising because labor income, meaning wages and salaries, were getting more concentrated. This corresponded to the emergence of the “working rich,” if you will. And then we discovered that since the beginning of the 21st century, income inequality has been rising not because of rising labor income concentration, but mainly because of rising capital income and wealth concentration. This means that at the top of the distribution of income, what’s booming these days is not really wages (which are high but not growing much faster than the economy), it’s dividends, capital gains, interest, rents, and business profits.

That’s important because the economic forces that shape the distribution of labor income are different than the economic forces that shape the distribution of capital income. For labor income, what matters is education, technology, union density, things like that. What matters to understand the distribution of capital income and wealth is saving rates, inheritance, rates of return to wealth, and so on. So, if you want to understand inequality, you need to have a clear view of what’s happening to labor income and capital income separately, so as to understand the deep economic forces that are shaping the distribution of income and its evolution.

Boushey: So, all this new data that you’re putting together allows you to look at those in the same dataset simultaneously?

Zucman: Exactly.

Boushey: And we haven’t been able to do that before?

Zucman: Not in a satisfactory way. Macroeconomists have been pointing out for some years now that the capital share of income is rising and the labor share is falling. But when you talk to people who study inequality, they don’t really see that because in their data—survey data—you don’t see a lot of capital income. In order to observe capital income, you need to reach out to wealthy individuals in survey data, which is hard to do in the context of surveys.

Boushey: And so you use tax data?

Zucman: We use a combination of survey data and tax data. In the tax data, the good thing is that we can see rich people because all rich people have to file an income tax return. But even tax data are not enough because there are many forms of capital income that are tax-exempt such as corporate retained earnings—the fraction of corporate profits that is not distributed to shareholders. That form of capital income remains within companies. It’s not taxable at the individual level and so you don’t see it in individual income-tax data. It turns out that this form of income has been growing fast since the beginning of 21st century.

Corporate retained earnings were completely ignored by the inequality literature because you don’t see them in traditional datasets. Many of these undistributed corporate earnings are in the Cayman Islands, in Bermuda, and in other offshore tax havens. Corporate retained earnings have increased from almost zero in the late 1990s to as much as 5 percent of GDP in recent years. Corporations are making a lot of profits and are saving a lot. If you just look at the dividends that people receive, it falls short of capturing the true scale of capital income in the United States today.

Understanding the importance of distributional national accounts

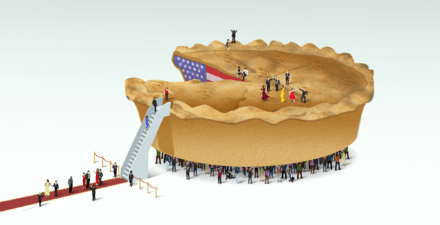

Boushey: Understanding capital income is super important, but another thing that you are able to show is when the U.S. economy grows by, say, 2 percent, who gains from that? One of the things that we hear a lot about in policy circles is that the U.S. economy is growing and it seems like everything is fine. So, why are people out there in America seeming so frustrated or seeming like their economic circumstances aren’t doing so well?

I think what’s exciting for me about this work is that you’re connecting those dots, so we can actually see that the economy is growing at the national level or in a particular state but this income is going to only a few folks or it’s going to these other forms of income that aren’t benefiting the middle class. I think that’s a real step forward for being able to understand the concerns of people that live in this country.

Zucman: Indeed, it’s important. For a long time, many people felt that it was enough to look at macroeconomic growth, which would indeed be the case if you have equitable economic growth. If income is growing at the same rate for everybody, then we don’t really need distributional national accounts. That was more or less the case in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But since then things have changed.

Growth has not been very high in the United States since 1980, with average income per adult growing by 1.4 percent a year on average only. That’s mediocre growth performance.

But what’s striking is that even this mediocre growth performance is much more than what’s been experienced by most of the population. Almost 90 percent of the population has seen its income grow by less than that. And for half of the U.S. population—about 120 million adults today—there’s been zero growth in average pretax income since 1980. This means that in 1980, for the bottom 50 percent, average income before government intervention was $16,000 a year, adjusted for inflation. Today, it’s still $16,000 a year. That’s a generation-long stagnation in income for half of the population.

And at the other end of the income spectrum, you’ve had extremely high growth rates, but for a tiny elite—that is, the 1 percent. I wish things were different, but this is what the data show. It’s not that the top 20 percent, for instance, are pulling apart from the rest of the country; it’s not that the top 10 percent are doing so, or even the top 5 percent. It’s the top 1 percent and finer groups within the 1 percent which are experiencing really high growth rates: the top 0.1 percent, the top 0.01 percent, and so on. With the distributional national accounts that we now have, we can study these tiny groups that were hard to capture before.

The significance of rising income inequality in the United States

Boushey: Let me turn to a slightly different question here: Just how significant is this increase in inequality in the United States? We just discussed the numbers on rising income inequality that come from your work, but my understanding is that recently some researchers have challenged your findings and contend that the rise in inequality is much smaller than what you estimate.

I don’t want to go down too much of a rabbit hole here, but I do want to spend a few minutes on some of the technical details while we have you. I really want to hear you tell us why you think these disagreements exist. I think a lot of people might think, “Oh, these are just measurement issues, these are just economists kind of battling it out.” Tell us why this is important and why two scholars can measure the same thing and come to different results.

Zucman: It’s mainly because we don’t measure the same thing. What we measure is, I think, the relevant thing to measure, namely the distribution of total national income—the total flow of income that accrues to U.S. residents or, in other words, the market value of everything that’s produced in the United States plus the net flow of income that the United States receives from the rest of the world.

Other attempts to study inequality in the United States don’t capture 100 percent of national income. Sometimes they capture less. Traditional tax-based studies only capture 60 percent of national income, in particular, because they miss those big corporate retained earnings we talked about. Sometimes they capture more than 100 percent of national income—for instance, when people count current transfers as income but don’t deduct taxes. So, then they get more than 100 percent of national income, which is not good either.

How income inequality in the United States compares to other countries

Zucman: With my colleagues, we’ve spent a lot of time trying to come up with a meaningful way to distribute just 100 percent of national income (no more, no less). And this is still a work in progress—and it will be a work in progress for many more years! But this work has one advantage: National income is a meaningful income concept, one that is comparable over time and across countries. Other studies have other qualities, but they don’t do this exercise of forcing themselves to distribute a conceptually meaningful income concept—something that you’re going to be able to do all around the world and over time in a consistent way.

Our goal is to construct distributional national accounts all over the world, so as to be able to make apples-to-apples international comparisons of inequality, in much the same way that economists compare the macroeconomic performance of countries by comparing GDP per capita or GDP growth.

International comparisons of income inequality are powerful because they reveal how unique the United States is among developed countries. This phenomenon of complete stagnation of income for the bottom half of the distribution seems to be specific to the United States. We’ve done similar computations in France using similar concepts, similar methods, making sure that we compare apples to apples. And what we find is that in France, the average income for the bottom half of the distribution has been growing about as fast as the overall economy—not very fast to be sure, but it’s been growing, whereas in the United States, it has completely stagnated.

Boushey: Equitable growth.

Zucman: Somewhat equitable growth—income inequality has still increased in France, but not nearly as much as in the United States. The consequence is that in 1980, the bottom half of the income distribution was richer in the United States than in France, but now it’s the other way around: The average pretax income of the bottom 50 percent is higher in France than in the United States. And here we’re talking about pretax and transfer income, so it’s not because of the French welfare state, it’s market income that’s higher for the bottom half in France than in the United States today. And this is despite the fact that people work more in the United States than in France, in particular because standard working hours are higher in the United States than in France.

This is a particularly important finding because it sheds light on what can (and cannot) explain the rise of inequality in the United States. There is this widespread view that rising inequality is a mechanical consequence of globalization and technical change, spurred in large part by competition with China and the substitutions between workers and machines.

But, you know, France has computers too, and also trades with China—and generally trades more than the United States. So, it does not seem possible to explain the stagnation of U.S. working-class income by globalization and technical change. It’s more likely that this stagnation of income for the bottom half of the U.S. income distribution comes from policy changes. Things such as the collapse of the federal minimum wage, the declining power of unions, changes to taxation, to access to higher education, etc.

Boushey: One of the things about these distributional national accounts is that you can only really do them because you have government data, the tax data. And because nearly a century ago, so many countries started to all adopt these national income and product accounts, these consistent accounting systems are now spread worldwide. So, it feels, in some ways, that you’re trying to start that same kind of movement for the 21st century for governments to change what they’re measuring. Is there any country or set of countries where you’re seeing more of an appetite among policymakers to do this?

Zucman: I think there’s a growing demand from the public everywhere around the world for this type of distributional national accounts. People realize that it’s not enough to know how GDP is growing, they want to know how income is growing for people like them. And you’re right to say that what’s happening today is similar to the process that happened for the national accounts in the first place.

In the first half and middle of the 20th century, a number of economists—Simon Kuznets in the United States, James Meade in the United Kingdom, Dugé de Bernonville in France, etc.—developed GDP accounting and the national accounts. And Kuznets and others, in parallel, looked at tax data to study the distribution of income as reported on tax returns. But they never bridged the gap between GDP and national income on the one hand, and the distribution of taxable income on the other. So, what we tried to do is to complete the Kuznets agenda of studying jointly GDP growth and the distribution of income, by doing these two things in a common and consistent conceptual framework.

What new research needs to be done on measuring economic inequality

Boushey: I have one last question. Equitable Growth is a grant-making institution. We fund a lot of different scholars, and we’re always looking to know what are the most important questions that we should be asking, especially in order to advance our understanding of how we should be thinking about measuring inequality and growth. Do you have any suggestions for us?

Zucman: I think that we can learn a lot with careful case studies of what happens in various countries over certain periods of time. Even if you are ultimately interested in the United States, you want to study the rest of the world because it’s going to teach you a lot about what specifically has gone wrong in the United States and has caused the rise in inequality. So, I would encourage more international and historical research. Ultimately, you learn from data.

Boushey: Wonderful. Thank you so much, Gabriel.

Zucman: Thank you.

Related

Simplified distributional national accounts

Disaggregating growth

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!