Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Michael Kades has authored this contribution.

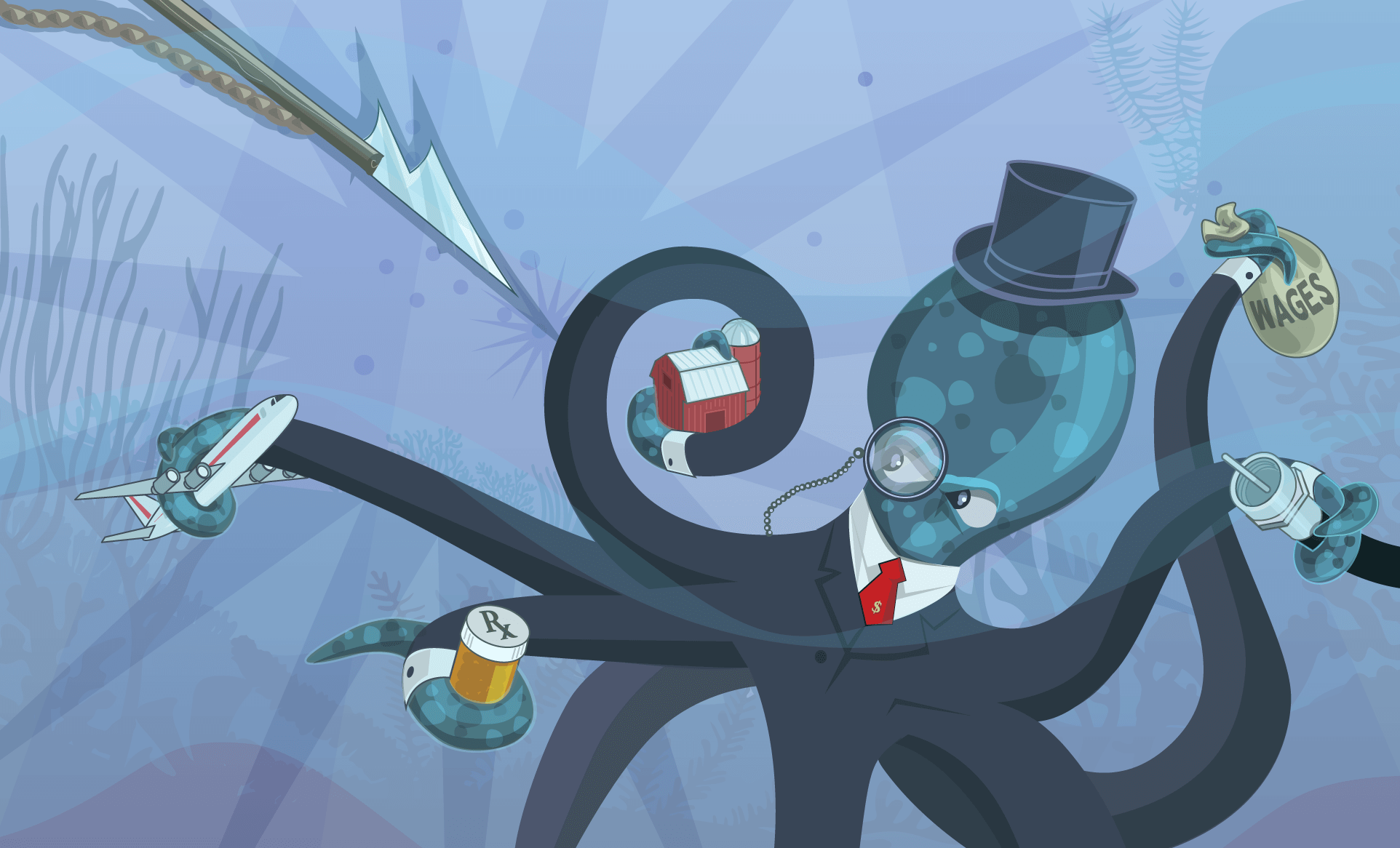

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

Market power and its abuse are far too prevalent in the U.S. economy, increasing the prices consumers pay, suppressing wage growth, limiting entrepreneurship, and exacerbating inequality. Equitable Growth’s 2020 antitrust transition report identifies a lack of deterrence as a key problem: “Antitrust enforcement faces a serious deterrence problem, if not a crisis.”

As the report explains, “Rather than deter anticompetitive behavior, current legal standards do the opposite: They encourage it because such conduct is likely to escape condemnation, and the benefits of violating the law far exceed the potential penalties.” In the face of such warnings, it is a particularly bad time for the Supreme Court to unanimously reject 40 years of lower court rulings and conclude that the Federal Trade Commission can neither force companies to give up the profits they earned by violating the law nor compensate the victims of those violations. (The first remedy is called disgorgement, and the second remedy is called restitution.)

Whether the Supreme Court in April correctly interpreted the statute at issue in the case, AMG Capital Management LLC v. Federal Trade Commission, is less important than its implications. Professor Andy Gavil discusses a potential silver lining in the Supreme Court’s decision—the glass-half-full approach. He argues that if the Supreme Court faithfully applies its approach to statutory interpretation, then it could open the door to broader application of the antitrust laws.

I look at the direct impact of the decision—the glass-half-empty approach. I argue that the decision deprives the antitrust agency of a critical, albeit imperfect, weapon that has deterred anticompetitive conduct particularly in the pharmaceutical industry. Although it has used disgorgement in competition cases sparingly, those awards have deterred the entire industry from engaging in the challenged conduct.

Before the recent Supreme Court decision, the disgorgement awards in competition cases went far beyond the impact in a single case. The savings include benefits from the conduct that did not occur. If the commission cannot seek monetary remedies, then companies will keep the rewards of their illegal conduct. Perversely, the companies causing the greatest harm will benefit the most from April’s decision.

The impact reaches even further. Without the threat of a disgorgement award, companies are more likely to drag out litigation and tax the FTC’s limited resources. Because the commission will spend more resources on egregious cases to reach weaker results, it will have fewer resources to challenge anticompetitive conduct in other areas and, for example, could affect enforcement in merger cases or in the high-tech industry.

On the bright side, Congress can easily restore the FTC’s ability to seek monetary remedies, and the idea has some bipartisan support. The remainder of this piece discusses how disgorgement has been a successful tool in antitrust cases and what we can expect if Congress does not restore the FTC’s ability to seek broader and more equitable remedies, including monetary relief.

Disgorgement as deterrence

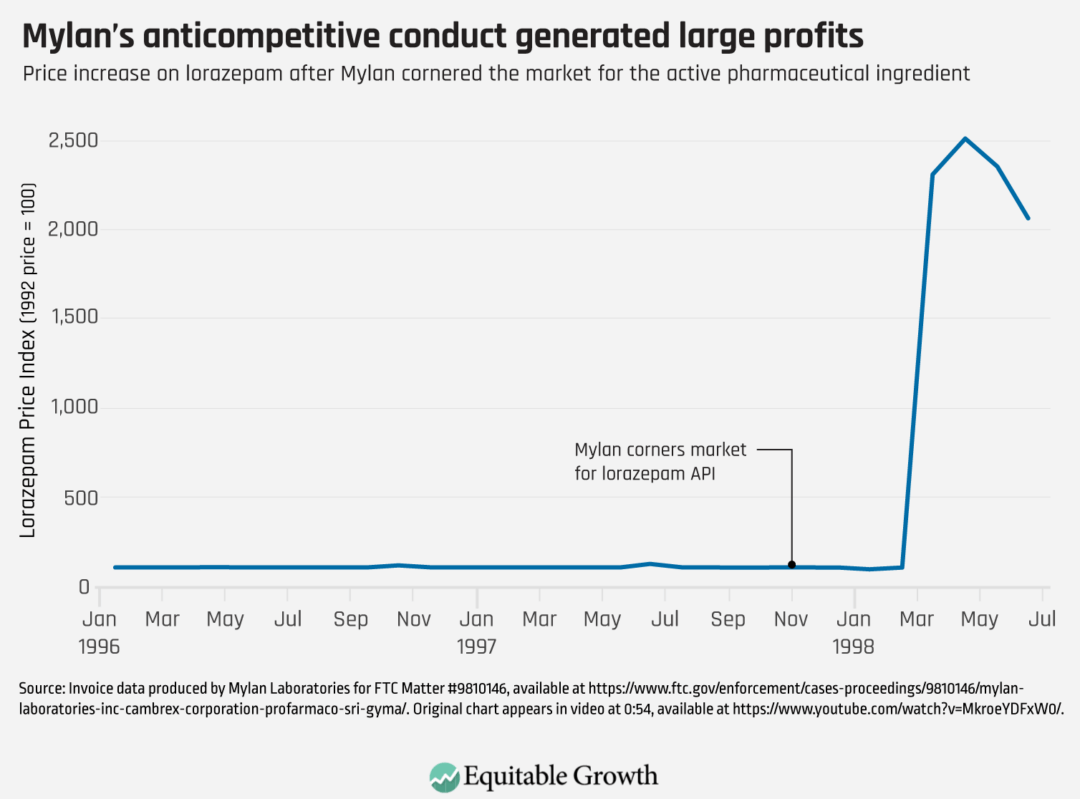

The story of the FTC’s monetary relief has come full circle. In 1998, the agency sued Mylan Laboratories Inc. to prevent it from continuing to corner the supply of a critical input (the active pharmaceutical ingredient) for a common tranquilizer, lorazepam. (I was one of the FTC attorneys on the case.) Mylan’s conduct forced its competitors to temporarily exit the market, and Mylan raised wholesale prices by 2,500 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Although Mylan’s competitors found new suppliers and reentered the generic market in a matter of months, Mylan had earned an additional $120 million in profit. The Federal Trade Commission and a group of state attorneys general sued, seeking to stop the conduct and to disgorge the profits Mylan earned. In settling the government actions, Mylan agreed to pay $100 million, which was distributed to consumers and state Medicaid plans that had paid the inflated prices.

Absent the monetary recovery, Mylan’s strategy would have been wildly successful, and others, seeing that success, could have repeated it in any market where there were few suppliers of an active pharmaceutical ingredient. Until recently, however, no pharmaceutical company appears to have tried Mylan’s strategy. By depriving Mylan of its illegal profits, the Federal Trade Commission sent the message to the industry that cornering supply was a game not worth the candle.

Some antitrust experts argue that the agency has no need for monetary remedies because private parties can obtain treble damages. Unfortunately, treble damages sound more effective than they are. A study by emeritus professor John M. Connor of Purdue University and Robert H. Lande, Venable professor of law at the University of Baltimore, found that, on average, private plaintiffs in cartel case settlements obtain just 19 percent of the actual, not trebled, damages.

Indeed, several factors limit the effectiveness of the treble-damage remedy. One is forced arbitration clauses. Another is specific procedural hurdles that private plaintiffs face that government enforcers do not. And a third factor is the limitations on who is a proper plaintiff. The FTC’s authority to seek monetary remedies was not duplicative of private actions but rather made antitrust enforcement more effective.

Disgorgement and the efficient resolution of litigation

Private actions, even if they were sufficient to deter anticompetitive conduct, would not address the other problem the Federal Trade Commission will face without a monetary remedy. When the agency is challenging an ongoing activity, the longer the defendants can delay resolution, the longer they can earn their ill-gotten profits. When the conduct yields hundreds of millions of dollars in profits, legal fees of millions or even tens of millions of dollars look like a good investment.

Now, in the wake of the recent Supreme Court ruling, imagine the Federal Trade Commission trying to stop the conduct, and even if it wins, the company gets to keep everything it earned. Under that scenario, defendants have every reason to string out litigation. Further, the commission will be in a weaker position to negotiate settlements.

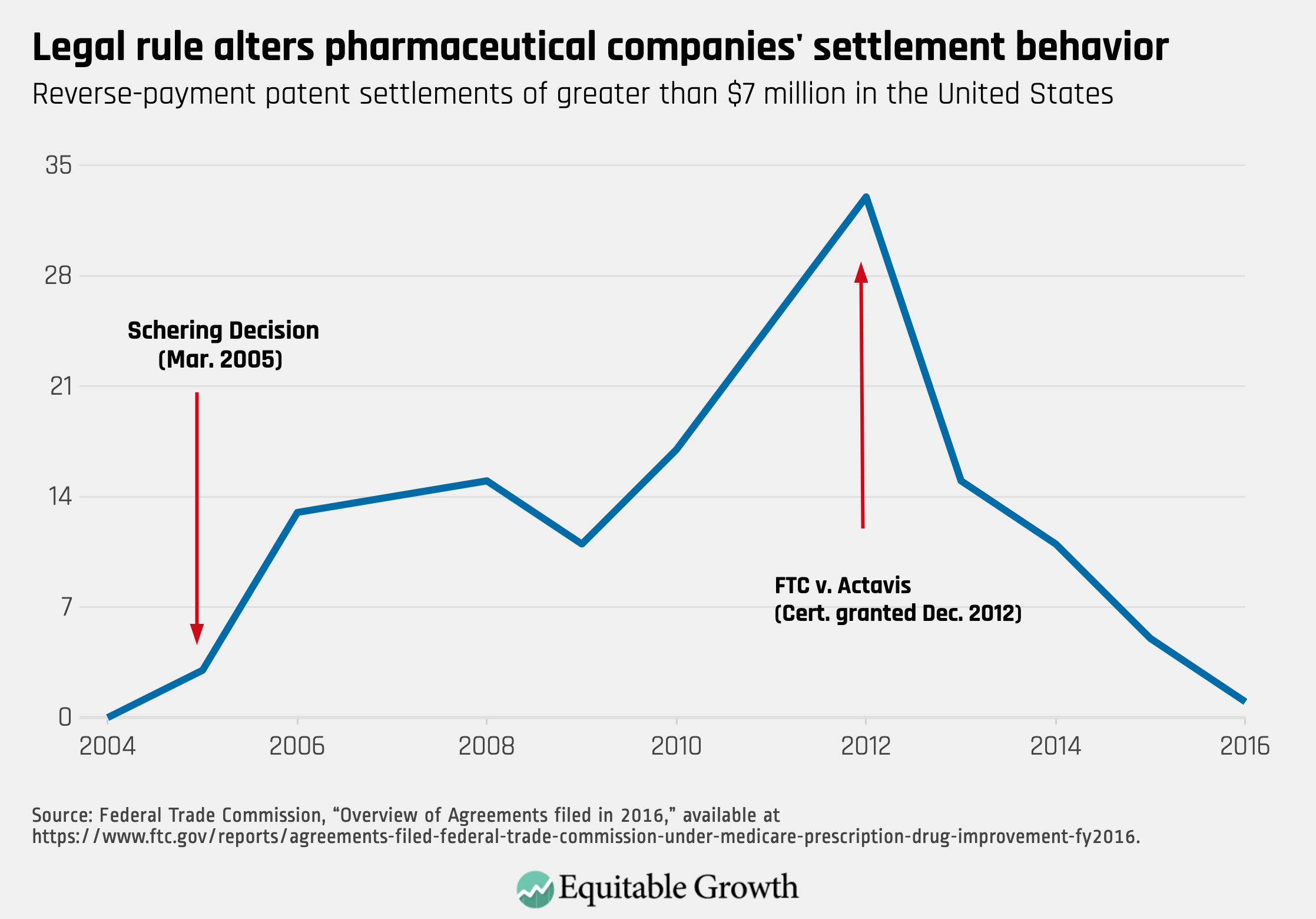

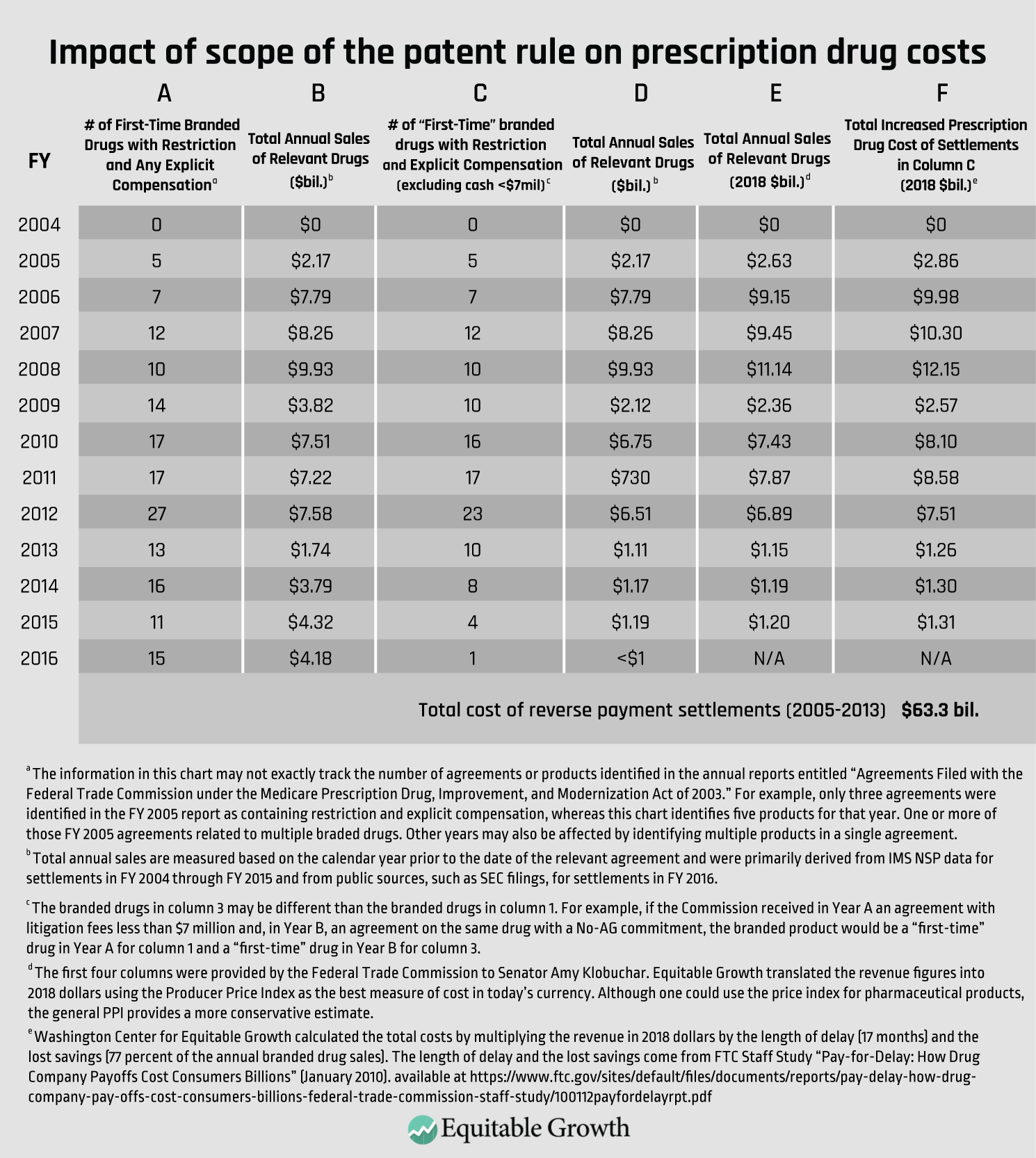

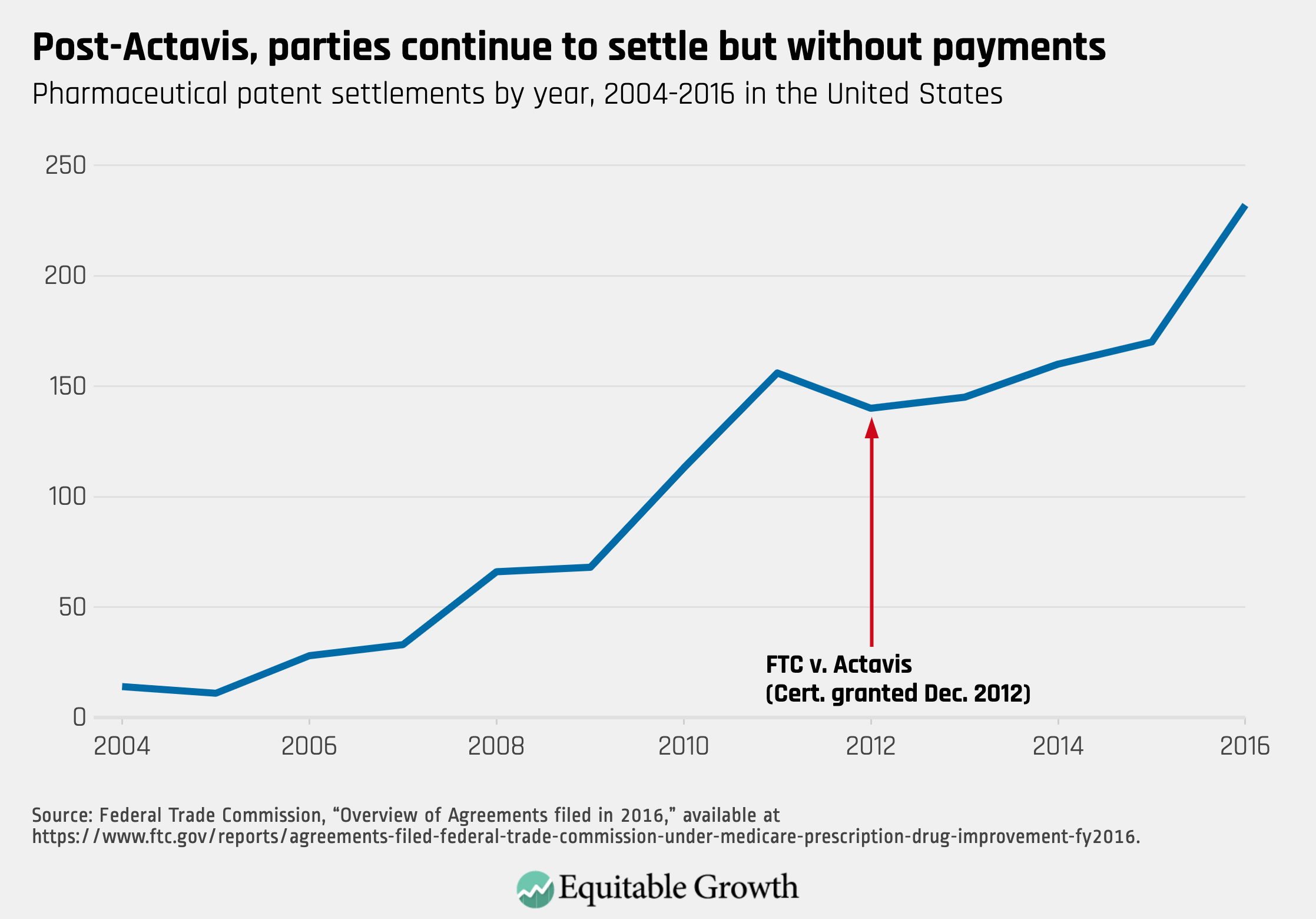

This scenario is not imaginary. In June 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis Inc. that patent settlements in which a branded pharmaceutical company paid a potential generic not to compete, known as pay-for-delay or reverse-payment agreements, could violate the antitrust laws. At the time, the agency had two active pay-for-delay cases, the Actavis case itself and Federal Trade Commission v. Cephalon Inc. (I worked on both.) In the Actavis case, the commission had relinquished its disgorgement claim, but it had not in the Cephalon case. In less than 2 years, it settled the Cephalon case, obtaining $1.2 billion in disgorgement and the company’s agreement not to enter future pay-for-delay agreements.

In contrast, in the case against Actavis, there was no threat of disgorgement and so it dragged on for more than 5 years before a settlement was reached—and it ended up being a weakerorder with no monetary remedy. The result was worse: longer time to resolution, more resources expended, and a weaker remedy.

Without a disgorgement remedy in antitrust cases, particularly in pharmaceutical ones, the more profitable the conduct, the less incentive the defendants will have to settle—even when they are likely to lose on the merits. In turn, the Federal Trade Commission will have to use more resources on easy cases and have fewer resources for more complex matters.

If you are concerned about monopolization in digital platform markets, consolidation in hospital markets, or any other anticompetitive activity, the impact of the Supreme Court’s AMG decision should bother you. Without the ability to obtain disgorgement, anticompetitive conduct will be more likely, and the commission will face more demands on its already-insufficient budget.

Liability without consequences

If companies can keep the profits they earn by violating the law, then companies can engage in egregious behavior without fear of the consequences. Take the FTC’s recent case against AbbVie Inc. The commission proved that AbbVie had brought objectively baseless patent litigation, that the burden and length of the litigation (litigation process, not its outcome) delayed generic competition, and that that the company illegally increased its profits by $448 billion.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit upheld the liability but concluded that the Federal Trade Commission could not deprive AbbVie of its illegal profits. The AbbViedecision was decided before the Supreme Court’s AMG decision and interpreted a different part of the Federal Trade Commission Act. Nonetheless, the AbbViecase exemplifies the limited impact of even successful FTC antitrust enforcement if the agency cannot seek monetary remedies.

Coming full circle?

Six years ago, Martin Shkreli, the so-called pharma bro, brought his hedge fund experience to prescription drugs. He acquired Daraprim, a drug used to treat a serious parasitic infection that can be deadly to babies and those with compromised immune systems. He then promptly raised the price from $13.50 per tablet to $750. The event triggered public outcry and unwanted attention on Shkreli, who is now in jail for securities fraud.

In addition to raising prices, Shkreli’s company made it more difficult, if not impossible, for new competitors to enter the market. It prevented generic companies from being able to obtain approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration through sample blocking, an anticompetitive tactic that Washington Center for Equitable Growth has discussed often and which Congress addressed through the CREATES Act in 2019. And, like Mylan, nearly 25 years earlier, Shkreli’s firm allegedly locked up the active pharmaceutical ingredient for Daraprim, creating a further hurdle to competition.

In 2020, the Federal Trade Commission sued, alleging both strategies were anticompetitive. Unlike in the Mylan case, after the AMG decision, the commission cannot seek monetary remedies such as restitution and disgorgement. Unless Congress acts, Shkreli and his co-defendants have no fear of losing the profits they earned through any anticompetitive and illegal activity. Regardless of the result in the Shkreli case, it is unlikely to deter anticompetitive conduct as strongly as the Mylan case did.

Status of a legislative solution

The fix is simple. The Supreme Court neither endorsed the fraudulent conduct at issue in the case nor suggested there was a constitutional objection to providing the Federal Trade Commission the authority to seek disgorgement or restitution. Congress can restore the authority the commission has been using for years by clarifying the scope of the FTC’s power.

On the surface, there appears to be strong bipartisan support for doing so. Within days of the Supreme Court’s AMG ruling, all four FTC commissioners called for legislative action. Both the then-acting chairwoman and the ranking member of the Senate Commerce Committee voiced support for a legislative fix. Recent hearings, however, in both the Senate Commerce Committee and in the House Commerce Committee suggest areas of disagreement over the scope of the legislation. The House did pass legislation with two Republicans voting in support last week.

Reforming U.S. antitrust enforcement and competition policy

February 18, 2020

The state of U.S. federal antitrust enforcement

September 17, 2019

Conclusion

After the AMG decision, much of the focus has been on how the decision limits the FTC’s ability to compensate victims of fraud and other consumer protection violations, which is understandable. The commission seeks monetary relief far more often in consumer protection cases (49 in 2019 alone) than in competition matters (14 total since 2000).

The decision’s impact on antitrust enforcement, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, however, should be equally troubling. The antitrust enforcement scheme can address the market power problem and the harms it causes only if it deters anticompetitive conduct in the first place. With companies no longer facing the threat of the Federal Trade Commission seeking restitution or disgorgement, violating the antitrust laws will be far more profitable than the dangers of being prosecuted. Perversely, the biggest winners from these developments are the companies that cause the greatest harm.

By no means were the FTC’s monetary remedies sufficient to completely deter anticompetitive activity. There is a robust debate about other powers the commission may already have to hold companies accountable, and recently introduced bills would give the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission the power to seek civil penalties for antitrust violations.

Civil penalties can be much larger than disgorgement, which is limited to the defendant’s illegal profits, or restitution, which is limited to harms consumers suffered. Policymakers should be discussing those issues and whether stronger remedies are needed rather than uncontroversial propositions such as whether companies that violate the antitrust laws should be allowed to retain the profits they earned through unlawful conduct and whether victims should be left uncompensated.

Before the AMG decision, a monetary remedy was the knife the Federal Trade Commission brought to a gunfight with pharmaceutical companies. Unless Congress acts, the commission will now arrive at the gunfight with only its bare knuckles.