Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, December 13–19, 2018

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

- Patent publication turns out to be a very valuable societal institution indeed, viewed as a way of disseminating knowledge, write Deepak Hegde, Kyle Herkenhoff, and Chenqi Zhu in “Patent Publication and Technology Spillovers”: “[I]nvention disclosure through patents (i) increases technology spillovers at the extensive and intensive margins; (ii) increases overlap between distant but related patents and decreases overlap between similar patents; (iii) lowers average inventive step, originality, and scope of new patents; (iv) decreases patent abandonments; and (v) increases patenting…”

- Workers—but only high-paid workers—capture about 30 cents of every extra dollar in revenue generated by the monopoly power conferred by a patent. This is another piece of evidence that workers—but again, only high-paid workers—are, to a substantial but not overwhelming extent, effective equity holders in American businesses. See “Who Profits from Patents? Rent-Sharing at Innovative Firms,” by Patrick Kline, Neviana Petkova, Heidi Williams, and Owen Zidar: “Comparing firms whose patent applications were initially allowed to those whose patent applications were initially rejected … patent allowances lead firms to increase employment, but entry wages and workforce composition are insensitive to patent decisions. … Workers capture roughly 30 cents of every dollar of patent-induced surplus in higher earnings. … These earnings effects are concentrated among men and workers in the top half of the earnings distribution, and are paired with corresponding improvements in worker retention among these groups…”

- Equitable Growth Steering Committee Member Karen Dynan, in a video conversation with Jay Shambaugh and Eduardo Porter about whether the U.S. government is properly prepared to fight the next recession, makes clear that the answer is no, in “What Tools Does the U.S. Have to Combat the Next Recession?” To paraphrase: Today’s lower equilibrium interest rates make it more likely that monetary policy would need to make use of unconventional tools to spur the economy. On the fiscal front, we have a much larger level of government debt relative to GDP than we did prior to the financial crisis. However, viewing this level of debt to GDP as a reason to restrain stimulus spending in case of a crisis could make the problem worse. Whether the government uses fiscal policy to stimulate the economy will depend more on political willingness, than on the actual limits on fiscal policy…

- An excellent interview with Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board Member Lisa Cook, “On invention gaps, hate-related violence, discrimination, and more,” where she says: “One of the first things I do [in Dakar, Senegal] is to buy a Bic pen. … Each one was 10 dollars! Ten dollars! This completely stunned me. I knew how poor most people were. I knew students had to have these pens to write in their blue books. It just started this whole train of thought…”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

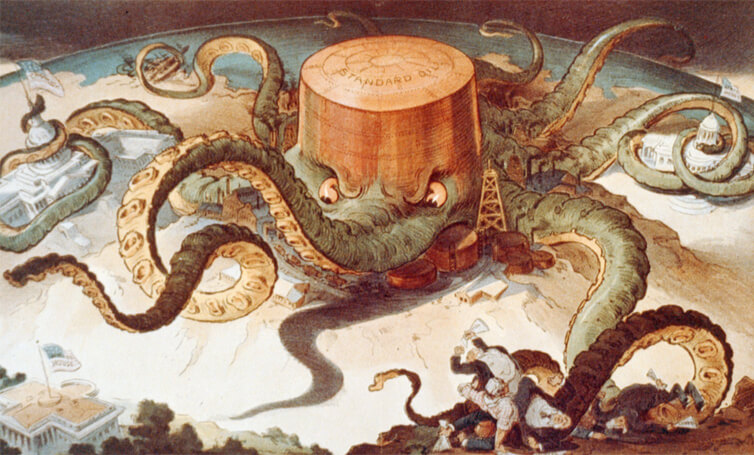

- Scale economies are not growing in the American economy. But monopoly power is, writes Jonathan Baker in “Market Power or Just Scale Economies?”: “Growing market power provides a better explanation for higher price-cost margins and rising concentration in many industries, declining economic dynamism, and other contemporary U.S. trends, than the most plausible benign alternative: increased scale economies and temporary returns to the first firms to adopt new information technologies (IT) in competitive markets. The benign alternative has an initial plausibility. … Yet six of the nine reasons I gave for thinking market power is substantial and widening in the U.S. in my testimony cannot be reconciled with the benign alternative. … None of the reasons is individually decisive: There are ways to question or push back against each. But their weaknesses are different, so, taken collectively, they paint a compelling picture of substantial and widening market power over the late 20th century and early 21st century…”

- Brink Lindsey, Will Wilkinson, Steven Teles, and Samuel Hammond write, in “The Center Can Hold: Public Policy for an Age of Extremes”: “We need both greater reliance on market competition and expanded, more robust, and better-crafted social insurance … government activism to enhance opportunity … less corrupt and more law-like governance … a new ideological lens: one that sees government and market not as either-or antagonists, but as necessary complements…”