Paid sick time and paid family and medical leave support workers in different ways and are both good for the broader U.S. economy

Workers often need paid time away from their jobs, whether they are experiencing a short-term flu, undergoing a surgery and recovery that will last a few weeks, caring for an ill family member, or welcoming a new child to their family. In the United States, two distinct types of paid time off can be used to address family and health needs—paid sick time and family and medical leave—though there is no federal guarantee for either one, meaning some workers do not have access to them.

Paid sick time allows workers to address short-term needs, such as going to a doctor’s appointment or recovering from the flu. Paid family and medical leave allows workers to address longer-term needs, from caring for a new child or a sick family member to addressing one’s own serious medical need, such as cancer. This issue brief describes both types of paid time off and their impacts on the broader U.S. economy. It then provides information about which workers can access paid sick time and paid family leave through their employers as well as the federal legislation that has been proposed to broaden access.

What is paid sick time, and how does it affect economic growth?

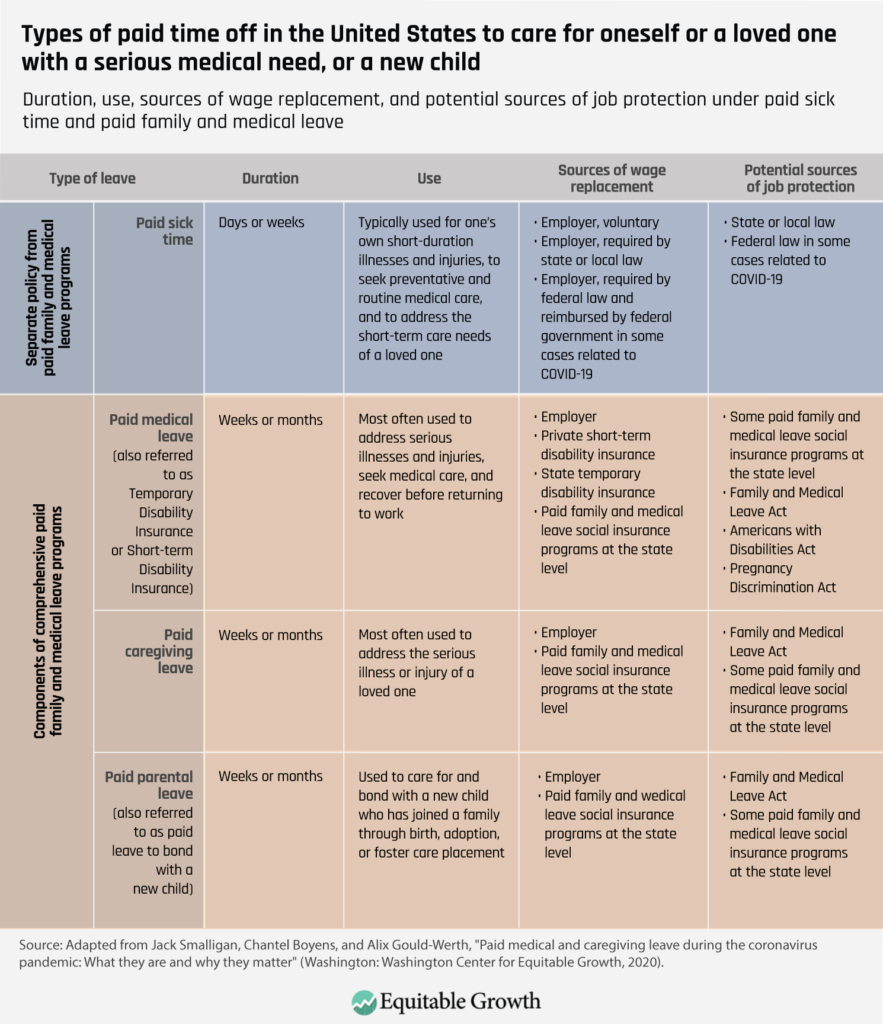

Paid sick time, also commonly referred to as paid sick days or paid sick leave, typically lasts for days or weeks, and can even be taken by the hour. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Paid sick time is typically used when a worker experiences an illness or injury that lasts a short time or when a worker needs to address a short-term care need of a loved one. It may also be used during preventative medical care appointments. Some employers voluntarily offer paid sick time to their workers, and currently 36 states and localities require that employers provide paid sick time, though workers have no federal right to paid sick time.

When employers choose to offer paid sick time, or are required to, their workers usually accrue that time as they work. For instance, an employer may offer 1 hour of paid sick time for every 30 hours that an employee works. When an employee has worked for 240 hours, they will have accrued 8 hours of paid time off to use when a health need arises. Additionally, some state and local paid sick time laws have a feature called “job protection,” which means that it is illegal for an employer to terminate an employee for using their paid sick time.

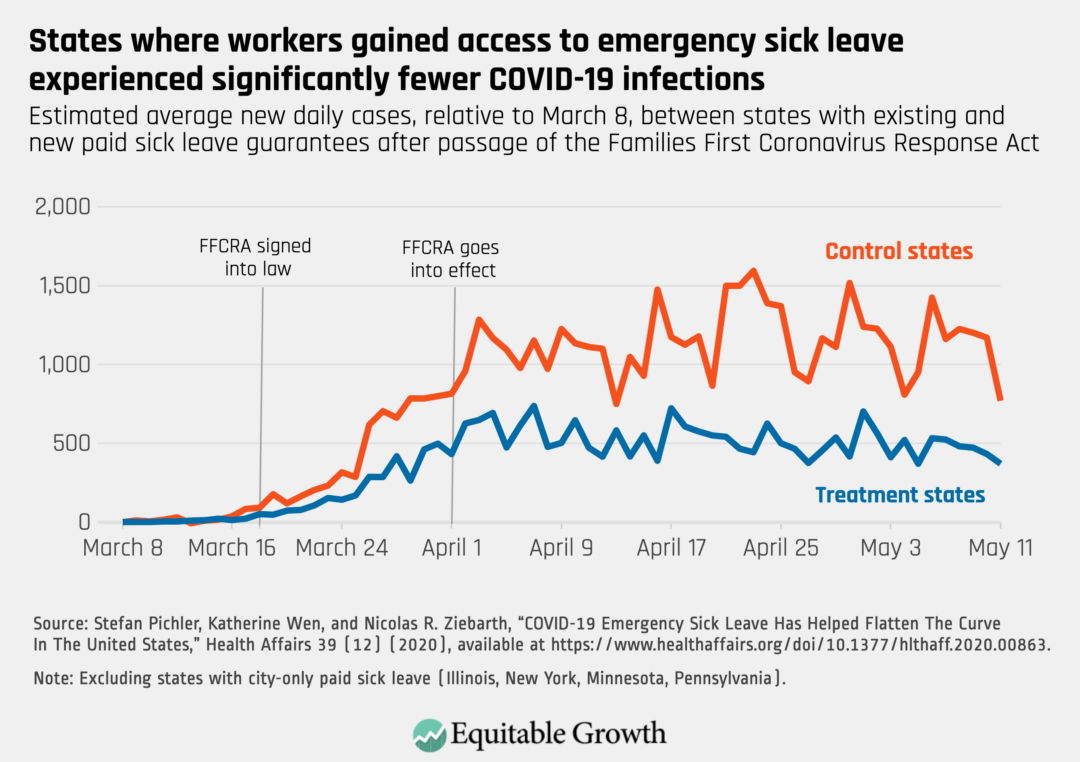

While the primary purpose of paid sick time is to allow workers to address short-term medical needs without suffering economic hardship, it also leads to broad economic and public health benefits because paid sick time is associated with decreases in the spread of communicable diseases. Local paid sick time laws, for example, have been found to reduce influenza-like infections by 30 percent to 40 percent. Similarly, when the federal government enacted a temporary, coronavirus-specific paid sick time policy in 2020 through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, states where workers gained new access to the emergency paid sick leave program saw COVID-19 cases drop by 56 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

As we have seen during the coronavirus pandemic, controlling communicable disease is essential to ensuring that workers are able to produce goods and services and that consumers will purchase those goods and services—in other words, to ensuring that large parts of the economy can function normally. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic was accompanied by an unprecedented drop in Gross Domestic Product precisely because the spread of infection hindered workers’ ability to work and consumers’ ability to consume.

Paid sick time policies also have been shown to reduce rates of worker turnover, which leads to productivity gains for businesses. When paid sick time policies are implemented, research shows that businesses do not cut other employer-provided benefits and are thus likely to be able to absorb the average cost of providing the benefits—2.7 cents per worker per hour, according to one study—with relatively little trouble.

What is paid family and medical leave, and how does it affect economic growth?

Paid sick time is important, but it is not well-suited to cover longer absences. When workers need weeks or months away from work to care for a new child or address a serious medical condition that they or a family member face, they turn to paid family and medical leave.

As seen above, in Table 1, there are three major components to paid family and medical leave:

- Paid medical leave to address one’s own serious medical condition, also known as temporary disability insurance

- Paid caregiving leave to care for a loved one with a serious medical condition

- Paid parental leave to care for and bond with a new child who has joined a family through birth, adoption, or foster care placement

Employers may choose to offer just one or two types of paid leave, but most of the states with paid leave programs offer comprehensive paid family and medical leave: all three types.

Pay for family and medical leave can be offered voluntarily by employers, who provide benefits directly or through third parties, such as private temporary disability insurance providers. Additionally, in 9 states and the District of Columbia, workers can access state paid leave programs, which offer workers partial wage replacement during their time away from work. Some state programs also offer job protection, so that workers can be confident that they can return to their jobs following their time off.

There is no federal program that provides paid family and medical leave to workers across the United States, though unpaid leave is available to some workers through the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Eligible workers can access job protection through these laws at the same time that they access pay from their employer or state paid leave program, where available.

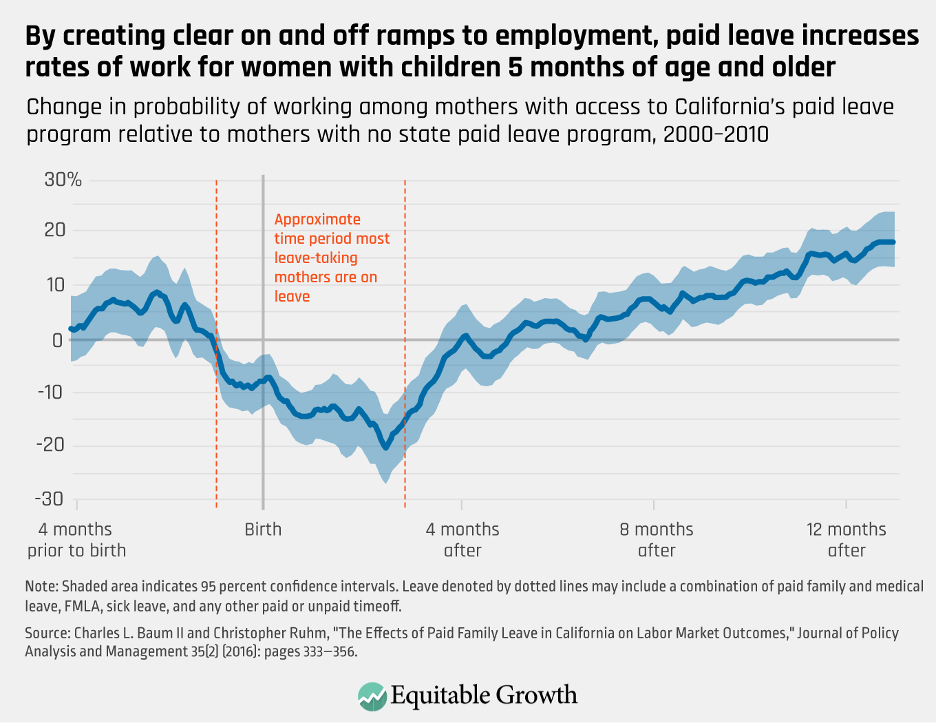

By allowing workers paid time off to address their family and medical needs, paid family and medical leave programs can contribute to macroeconomic growth. Paid leave programs, for example, can increase labor force participation, particularly among women, which is a key driver of economic growth. Evidence from California indicates that under the state’s paid leave law, new mothers are 18 percentage points more likely to be working a year after the birth of their child. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Other research finds that the availability of paid caregiving leave also affects work effort, either by increasing labor force participation or by increasing the number of hours worked among employed caregivers. Given these benefits, perhaps it comes as no surprise that research repeatedly shows that small businesses appreciate government paid family and medical leave programs.

Paid family and medical leave programs also strengthen the human capital of the next generation through improvements in child well-being, such as decreases in rates of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, obesity, and ear infections and the hearing problems they cause, along with increases in parents’ time helping children with reading and homework.

Who can access these types of leave, and what legislation might broaden access?

Despite the health and economic benefits of paid sick time and paid family and medical leave, many workers cannot access these types of paid time off.

Access to paid sick time is broad—but not universal—among the civilian workforce as a whole: Seventy-eight percent of workers can access paid sick time through their employer. But paid sick time is out of reach for the typical low-income worker. Only 4 in 10 workers in the lowest-paid jobs, who are disproportionately workers of color, have access to paid sick time.

Access to paid family and medical leave is even less common. Only 1 in 5 workers have access to paid family leave through their employers, and the figure drops to around 1 in 20 for the lowest-paid workers.

Federal legislation has been proposed to address these gaps in access. The Build Back Better Act, which was passed by the U.S. House of Representatives last year but remains stalled in the U.S. Senate, includes a proposal to establish a paid family and medical leave program, but does not include a paid sick time policy. Coronavirus-specific paid sick time was available until the end of 2020 through the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, and the Healthy Families Act would extend a broader guarantee of paid sick time.

Paid medical leave research

April 30, 2020

The economic evidence behind 10 policies in the Build Back Better Act

November 24, 2021

Conclusion

Because legislation that guarantees paid sick time and legislation that guarantees paid family and medical leave both allow workers to take needed time away from work without financial hardship, these policies are often conflated. Understanding the distinction between them, however, is important to conducting rigorous research and policy analysis—and ultimately to ensuring that policies are passed that ensure that workers can access leave to address whatever health issue they or a loved one faces, thus encouraging long-run economic growth and benefitting the overall U.S. economy.