(This issue brief draws on a longer report by Jane Waldfogel and Emma Liebman, “Paid Family Care Leave: A missing piece in the U.S. social insurance system.”)

Overview

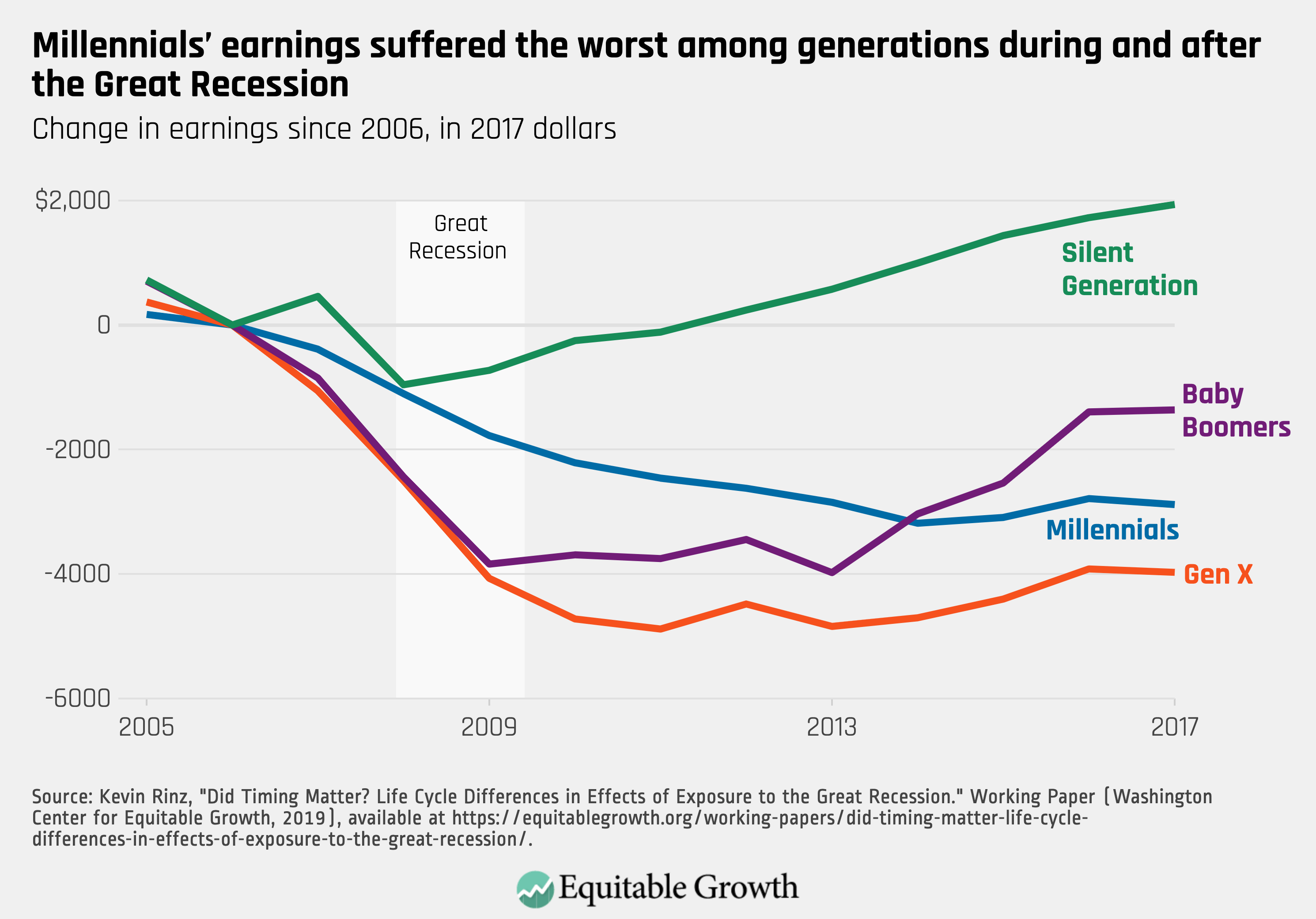

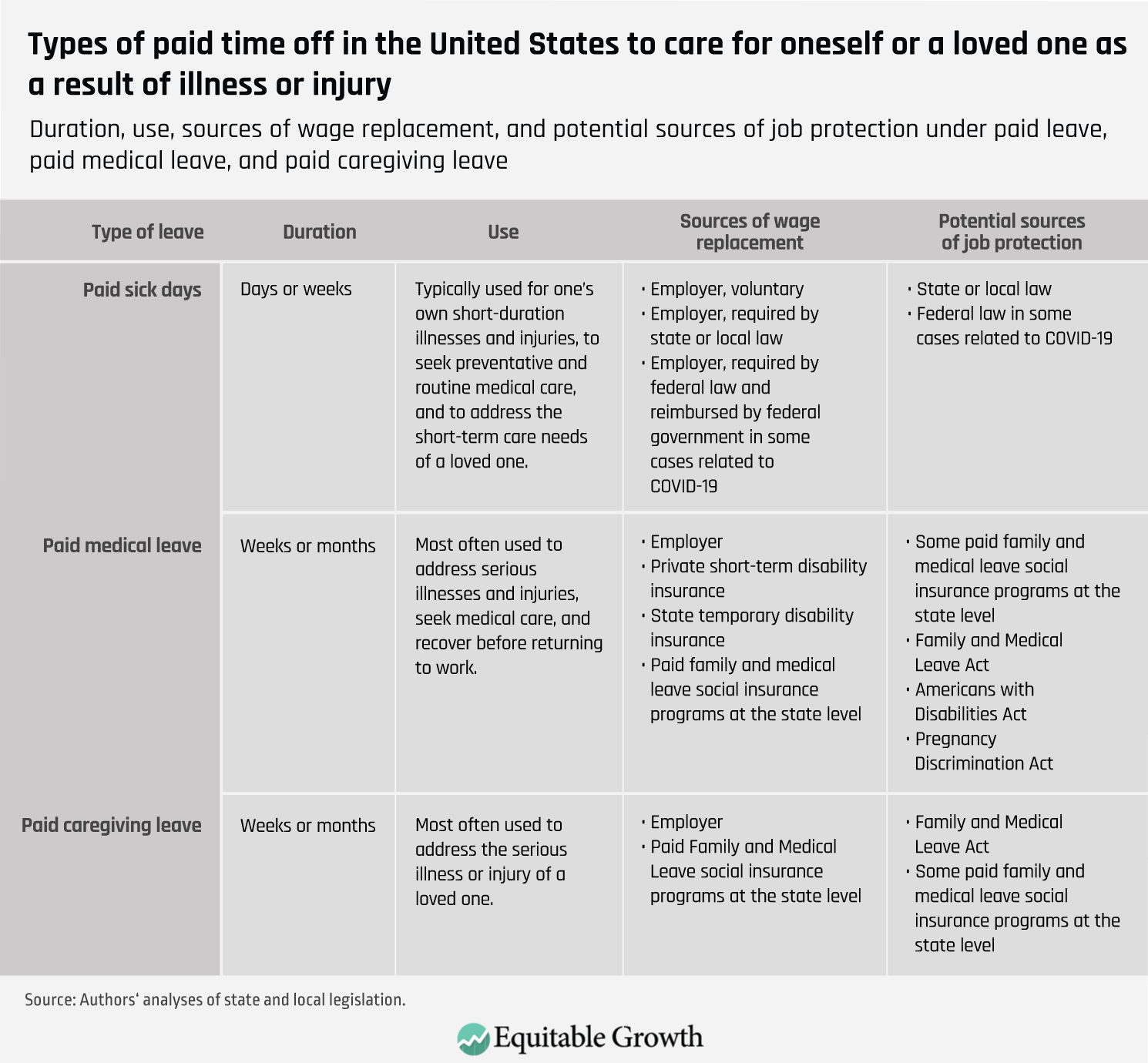

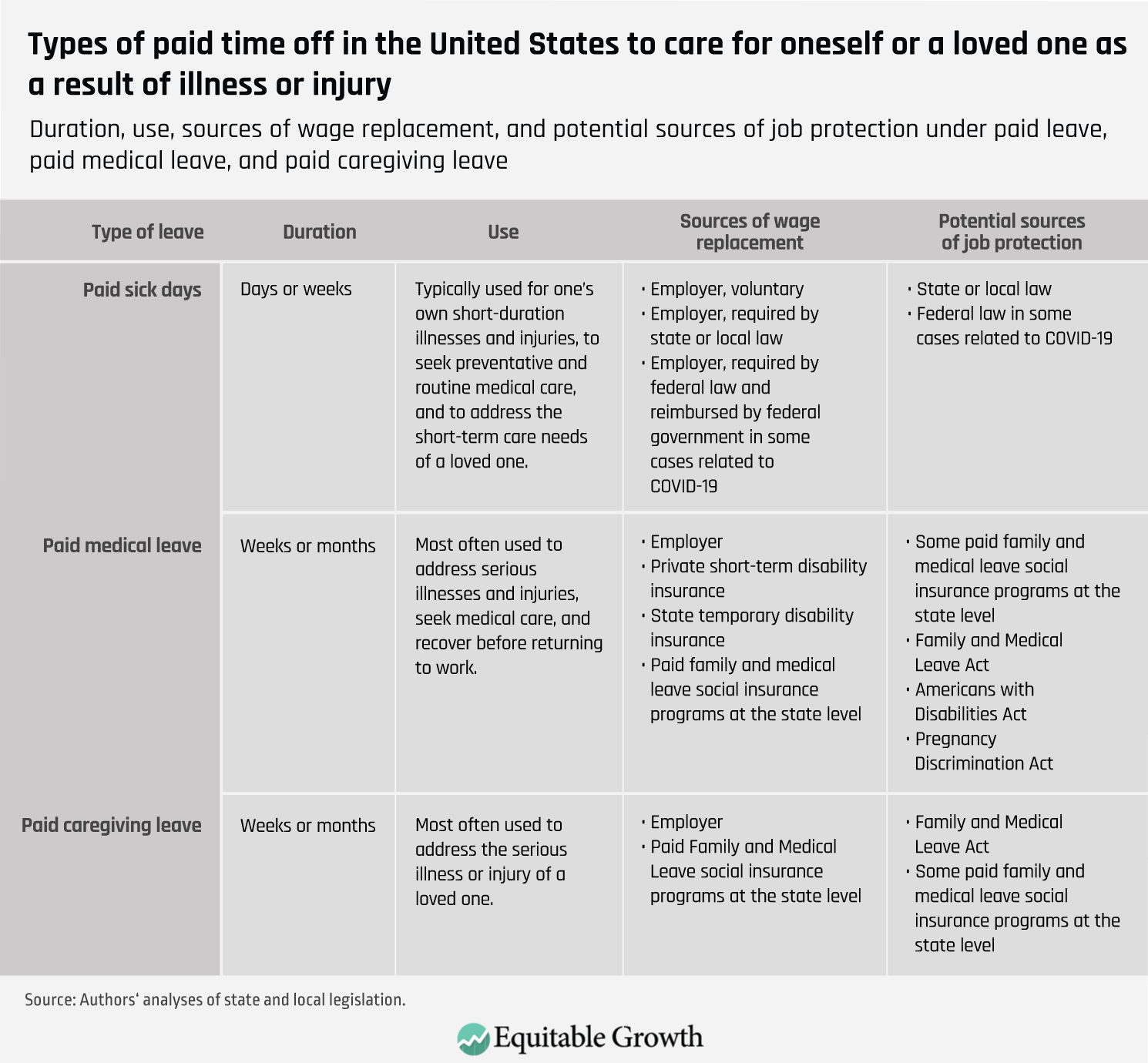

In response to the new coronavirus health crisis, workers across the United States need paid time off to deal with their health needs and the health needs of loved ones. At the state level, three main types of paid time away from work are provided to meet these needs: paid sick days, paid medical leave, and paid caregiving leave. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

The traditional mechanics of paid sick days in the United States are perhaps the most familiar to most people. As a worker amasses more hours on the job, she accrues time off at her full rate of pay to cover a few days of absence from work to attend to short-term medical needs. People use paid sick days to attend doctor’s appointments, recover from short-term illnesses such as colds, and to care for family members with short-term ailments. Paid sick days are offered voluntarily by many employers, and laws in many states and municipalities guarantee workers the right to earn paid sick days. Recently passed federal law gives some workers access to paid sick days for needs related to COVID-19, the scientific name for the disease caused by the new coronavirus, if they work for a qualifying employer.

Download File

Paid medical and caregiving leave during the coronavirus pandemic: What they are and why they matter

Paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave may be less familiar concepts. The term “paid family and medical leave” often conjures the image of leave to care for a new child. Yet paid leave encompasses much more. Paid family and medical leave programs at the state level typically cover four types of paid time off:

- Leave to bond with a new child

- Leave related to a spouse’s active duty military service

- Leave to deal with one’s own serious medical issue

- Leave to care for a loved one with a serious medical condition

Though some employers provide paid medical leave through private Temporary Disability Insurance providers, paid caregiving leave is not widely provided by employers. Large swaths of the U.S. workforce have no access to paid medical leave, nor to paid caregiving leave.

Over the past two decades, eight states and the District of Columbia have sought to extend coverage to more workers, passing laws that provide the workforce with both paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave. There is wide variation in leave length, but typical state policies allow for 6 weeks to 26 weeks of leave with partial wage replacement.

These programs are funded using a social insurance model, such as the Social Security program and the Unemployment Insurance program. A small payroll tax is collected to fund benefits for eligible workers who need time off with wage replacement when a qualifying event occurs. Some state paid leave programs provide job protection—the right to return to your job when your leave finishes—and some do not.

There are other legal protections at the federal level that give workers the right to unpaid leave that is job protected: the Family Medical Leave Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. If a worker’s state paid leave program does not offer job protection, then, as a work-around, she can take job-protected unpaid leave through the Family Medical Leave Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, or the Pregnancy Discrimination Act simultaneously with unprotected paid leave. Not all workers qualify for these federal protections, so some must take paid leave without a guarantee that their job will be available when they return.

When a personal medical need, family caretaking need, or public health crisis emerges, paid time away from work is critical for individuals, families, public health, and the broader economy. For decades prior to the new coronavirus crisis and looming coronavirus recession, Congress failed to establish a social insurance program providing wage replacement during personal medical leave and caregiving leave. Perhaps one reason that Congress has failed to act is a shortage of information on what precisely paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave are and what benefits they bring to individuals, family members, businesses, and the economy as a whole. Below, we discuss paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave in turn. We cover the evidence base on how medical leave and caregiving leave affect both health and economic outcomes.

Paid medical leave

To best draw conclusions on how paid medical leave affects people’s health and finances, we would look to causal inference studies that evaluate the effects of social insurance programs that provide paid medical leave. However, researchers rely on policy variation to draw conclusions about the effects of programs, and for paid medical leave, policy variation has been poorly timed. Rhode Island, California, New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, and Hawaii all launched programs prior to 1970—when data quality was limited—and their programs have remained relatively unchanged over time. The next paid medical leave program to be implemented was in Washington state, in 2020, and not enough time has passed to evaluate that program.

As a result, very few studies have been conducted on paid medical leave specifically. Yet by looking at the literature on private Temporary Disability Insurance and paid sick days, we can gather important information on how paid medical leave is likely to affect the health and economic outcomes of those who take it.

Health outcomes

Research on the impact of paid medical leave on health outcomes is still emerging. Evidence to date suggests there are several different mechanisms through which paid medical leave may have an effect. These include improved health management, reduced financial stress, and improved public health. Let’s examine each in turn.

Health management

One of the strongest signals that paid medical leave may impact health outcomes comes from research on paid sick days. Broadly speaking, having access to paid sick days is associated with a significantly lower risk of mortality across a wide range of conditions. The nature of this relationship is still being studied, but evidence suggests access to paid sick days better enables workers to manage a new health condition, for instance by seeking preventative care and earlier treatment of conditions.

Data from the National Health Interview Survey appears to support this idea. One study found that workers with access to paid sick days were significantly more likely to seek preventive medical care, such as mammograms, pap tests, and endoscopies, than other workers after controlling for other factors. Studies have also found that when workers have access to sick leave, they take more time off work for health-related reasons. Studies also find workers visit emergency rooms less. This suggests that workers with paid leave may be better able to schedule medical appointments, thereby avoiding the use of emergency rooms for less-urgent conditions.

Conversely, workers without access to paid sick days are significantly less likely to receive preventive health screenings, even when they are aware that they face higher medical risks. These findings are also important because early treatment of a health condition has been found to reduce the severity and duration of the condition.

Delaying or forgoing leave while sick or injured can have serious health consequences. One longitudinal study of a cohort of British civil servants, known as the Whitehall II study, found that unhealthy men who took no sick leave were twice as likely to experience a serious coronary event, compared to unhealthy men who took moderate amounts of sick leave. Similarly, a study that linked responses to a survey of Danish workers with administrative data on social welfare payments found that respondents who went to work ill more than six times over the past year had a 53 percent higher risk of taking medical leave for at least two weeks and a 74 percent higher risk of taking leave for more than 2 months after adjusting for confounding factors.

But not all the evidence is clear or consistent. A doctoral dissertation using the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which provides a 2-year follow-up to the National Health Interview Survey, did not find clear patterns of a change in leave-taking when workers experienced a job change that makes them lose or gain access to paid sick days.

Stress reduction

Paid medical leave may also improve health outcomes for workers by reducing stress associated with a financial insecurity due to a health shock. Taking time away from work to address a medical condition is a common source of financial strain for workers and families, one that can also add stress on workers who are already concerned with their health. Stress, regardless of its source, has been shown to negatively impact physical and mental health. In addition, research from developed countries shows that income levels directly affect mortality. Research also finds that severe debt is correlated with poor health.

To the extent that paid medical leave reduces stress associated with financial strain, it could also lead to improved health for workers. Research on the impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit and disability benefits suggests income supports can have significant positive effects. A study of the impact of an increase in this tax credit in 1993 was associated with an improvement in maternal health. It is thought that a reduction in financial stress was an important factor.

Similarly, a study taking advantage of the discontinuities in the Social Security Disability Insurance benefit formula finds “that $1,000 in annual SSDI payments decreases the annual mortality rate of lower-income beneficiaries by approximately 0.1 to 0.25 percentage points.” Beneficiaries with higher past earnings and the largest disability benefits did not experience the same benefits.

Public health

The literature on paid sick days suggests paid time off to address certain illnesses may have important positive effects on public health by helping to reduce the spread of contagious diseases. This evidence could have implications for medical leave or show opportunities for new research.

An analysis of local and state sick leave mandates in the United States using Google Flu Trend data found a significant reduction in the general flu rate after the mandates were implemented. These public health benefits also have spillover benefits for employers through reduced absenteeism. One study using seven panels of the Medical Expenditure Panel Study—which surveys people, their employers, and their healthcare providers—concluded that paid sick days reduce overall absenteeism by reducing the spread of influenza-like illness. The study estimated that reduced absenteeism due to paid sick days could have saved employers $630 million to $1.88 billion per year in 2016 dollars. It is possible that paid medical leave could also impact public health, but to what extent is unclear. Paid medical leave could be important to people suffering from complications due to COVID-19.

Economic outcomes

Serious medical conditions that require time away from work can pose a threat to workers’ economic well-being. They can lead to an immediate reduction in income from wages while the worker is on leave, an increase in out-of-pocket expenses for medical care, and a heightened risk of job loss.

Employers and the broader economy are also affected when work-limiting medical conditions lead to worker absences, reductions in productivity, and the loss of skilled staff. Government programs and spending also are affected when workers lose wages and employment, and must turn to public assistance programs for support.

Paid medical leave could help address these challenges, but existing research on the direct effects of paid medical leave specifically is scant and is limited to specific medical conditions. But related research on sick leave, income security, occupational health, and disability programs suggests paid medical leave could affect economic outcomes by reducing income volatility, helping workers to return to employment after taking leave, reducing productivity loses due to presenteeism, and supporting greater labor supply and long-term labor force participation.

Income shocks

Work-limiting medical conditions that threaten a worker’s economic stability often arise suddenly. These health and income shocks can put many medium- and low-wage workers and their families at risk of hardship when a medical condition forces someone to stop working for a period of time. A 2015 study by The Pew Charitable Trusts found that 1 in 3 families report having no savings at all and that approximately 41 percent of families did not have enough emergency funding to cover an unexpected $2,000 expense. For these families, taking weeks of leave to address a health condition without wage replacement would be very difficult or even catastrophic. A median worker’s weekly earnings, for example, in the third quarter of 2019 was $360, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. For this median-wage worker, 12 weeks of unpaid medical leave would reduce gross take home pay by $4,320.

Income disruptions make families significantly more likely to face eviction and to miss payments for housing and utilities. Families dependent on a single wage earner are especially vulnerable. Research on savings and assets, however, shows that even small amounts of savings can help families weather income disruptions. While 21.1 percent of families with savings of $249 or less missed a housing payment, that percentage falls to 15.2 percent when families have savings of between $250 and $749. Similarly, the additional income available to workers through paid medical leave could boost family finances enough to improve their ability to weather health-related income disruptions.

For many workers, a loss of wages due to medical leave is often further compounded by an increase in out-of-pocket medical expenditures, an important factor in analyzing the potential consequences for workers and families. A study of the 2007–2008 panel of the Medical Expenditure Panel Study found workers with a temporary disability pay approximately 22 percent of their healthcare expenditures out of pocket, or an average of $388. More broadly, the Federal Reserve found that “one-fifth of adults had major, unexpected medical bills to pay,” with these bills most often totaling between $1,000 and $4,999, and about 40 percent of those with bills had unpaid debt.

A Journal of the American Medical Association research letter summarized a survey of patients with stage III colorectal cancer that found respondents without paid sick or medical leave reported significantly higher personal financial burdens, including a higher rate of borrowing money and having difficulty making credit card payments, and a significantly greater likelihood of leaving their job. In addition, workers who lose their job may also lose access to employer-provided health insurance.

The consequences of unmitigated economic shocks due to medical problems extend across people’s financial lives and affect participation in social programs. The onset of poor health is a significant factor in early withdrawals of 401(k) retirement savings plans. Paid medical leave could help workers avoid or reduce the extent to which they tap retirement savings to deal with health shocks. For lower-income workers eligible for means-tested programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, taking unpaid medical leave could increase their benefits. Using National Health Interview Survey data and controlling for many factors, one study found that working-age adults without paid sick days are 1.41 times more likely to receive income from a state or county welfare program and 1.34 times more likely to receive Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits. When workers receive paid leave benefits, however, they contribute additional tax revenue based on those benefits. To the extent that paid medical leave supports labor force participation, it also leads to higher contributions to the Social Security trust funds, both strengthening the program’s finances and increasing their retirement benefits.

Labor force participation

Creating a new paid medical leave benefit could have implications for long-term labor force participation. Yet the nature of the relationship between such a benefit and labor supply is complex and not fully understood.

In the short term, access to paid medical leave may reduce the risk of job separations. One study using several panels of the Medical Expenditure Panel Study found that access to paid sick days reduced job separations, suggesting paid medical leave may have a similar effect. More specifically, the study found that, after controlling for many worker and job characteristics, “paid sick days decreases the probability of job separation by at least 2.5 percentage points, or 25 percent.” This effect is comparable to what has been found with employer-provided health insurance. In addition, some experts suggest that a medical leave or short-term disability benefit creates an opportunity for employers to provide supports and accommodations that could improve overall labor force participation.

Over the longer term, some research suggests that the provision of short-term disability benefits, which are typically offered for a duration of six months or longer can increase applications to long-term disability insurance by reducing the costs associated with the long waiting period for those benefits. However, studies are mixed on the extent to which this effect is seen in actual labor force participation.

Further, it is not clear whether or how these findings pertain to shorter-duration paid medical leave benefits, such as those that only last 12 weeks. One study that looked at a change in German law to reduce the generosity of benefits for sick leaves lasting longer than six weeks found no evidence that the duration of absences decreased, as would be expected if a significant moral hazard existed. The study also found, however, that lower-income and middle-aged subgroups may be more sensitive to these changes. Similarly, one study used the gradual phase-in of nine city-level and four state-level sick leave pay mandates on employers and found neither employment nor wage growth was significantly affected.

Paid caregiving leave

The first state to implement a social insurance program covering paid caregiving leave was California, in 2004. New Jersey followed in 2009, and then Rhode Island (2013), New York (2018), and Washington state (2020) followed suit. The evidence thus far suggests that the state programs are popular, though perhaps underused. Each of these states implemented paid leave to bond with a new child (often referred to as “parental leave”) simultaneously to their enactment of paid caregiving leave (leave to care for older children and other family members), and most of the research literature to date has focused on paid parental leave, which is more commonly used than paid caregiving leave.

This larger body of work on paid parental leave, however, is instructive in thinking about the likely health and economic effects of paid caregiving leave. Here’s what we know from the available evidence.

Health outcomes

Evidence from parental leave studies indicates that state paid leave programs improve caregiver and care recipient health, suggesting that time with pay to focus on caregiving responsibilities helps caregivers maintain their own health, as well as care for others. One study using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics to examine outcomes for parents of young children in California found that the introduction of paid family and medical leave improved the self-rated health of caregivers, as well as improving psychological health for mothers and reducing alcohol use for fathers.

Similarly, an Australian study found that the introduction of a national paid maternity leave program led to small improvements in both mental and physical health for mothers. And more research from California shows improvements in child health, as well as a 10 percent to 24 percent improvement in maternal mental health, suggesting that paid caregiving leave can yield dividends for the care recipient and caregiver alike.

Research on home-based care also offers suggestions about the health outcomes we might expect from caregiving leave. A 2019 study, for example, that used data from a demonstration project that randomly assigned cash allowances to Medicaid beneficiaries eligible for homecare, found that increased family involvement in home-based care improves health outcomes for the care recipient. The study found that recipients had a lower likelihood of emergency room use and lower incidences of bed sores and infections.

Taken together, these results are promising. Still, they are by no means exhaustive. More comprehensive research is needed to establish that state caregiving paid leave provisions improve health outcomes for leave-takers and care recipients across the board.

Economic outcomes

By providing workers with partial wage replacement during time away from work while caring for a loved one, paid caregiving leave has the potential to improve economic outcomes for workers and employers. The research literature suggests that caregiving leave is likely to boost labor force participation without harming employers.

Labor force participation

With the exception of a small number of studies, the bulk of the evidence suggests that paid leave for new parents increases labor force participation. The research suggests that paid parental leave in California, for example, increased the likelihood that a new mother was working a year after the birth of her child by 18 percentage points, and 2 years following the birth, mothers’ work hours and their weeks at work were 18 percentage points and 11 percentage points higher, respectively, than comparable mothers prior to the implementation of the paid leave policy. Perhaps these increases in labor force participation ameliorate poverty for the most vulnerable caregivers of new children. One study finds that the introduction of paid leave in California is tied to a 10.2 percent decrease in the risk of new mothers dropping below the poverty threshold and disproportionately helps women with lower levels of education and who are unmarried.

While the evidence base is comparatively thin with regard to caregiving leave, one study finds that following the implementation of paid leave in California, labor force participation of caregivers increased by 8 percent in the short run and even further (14 percent) in the long run. This effect was concentrated among women.

Employer responses

Employer responses to paid family leave programs in California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island have been predominantly neutral or positive. Although there had been some concerns before the laws went into effect about the potential costs associated with paid leave entitlements—such as increased administrative burdens or the need for firms to hire temporary replacements—the majority of employers across all states with operational paid leave programs and across all firm sizes have reported neutral or positive attitudes toward the laws. In a 2011 survey analyzing the California paid family leave program, 90 percent of employers reported that the program had a neutral or positive effect on profitability, and 8.8 percent reported that the paid family leave program had saved their firm money.

Similarly, a study of New Jersey’s paid family leave program found that 10 percent of employers felt that the program had a negative effect on the firm’s profitability, with 80 percent reporting neutral experiences and another 10 percent reporting that the program increased profitability. Research comparing employer responses before and after Rhode Island’s law went into effect found that the law had no overall impact on employers, and that two-thirds of employers were somewhat or very supportive of the law. A similar survey also found that two-thirds of employers in New Jersey were supportive of the law.

The lack of negative responses on the part of employers in California, New Jersey, and Rhode Island probably is because many employers are able to avoid hiring a new employee during the leave period of the absent employee and instead can distribute that leave-taker’s work to other employees. In addition, for employers who previously relied on their own paid leave provisions, paid leave programs could potentially decrease costs by allowing the state payroll tax to foot the bill rather than paying employees themselves.

Conclusion

As of the publication of this brief, Congress has failed to provide paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave to any workers in the United States, even those affected by COVID-19. The recently introduced PAID Leave Act would extend these benefits to workers affected by COVID-19 and a broader range of medical problems. The rise of COVID-19 shines a light on the need for permanent paid caregiving and medical leave enacted at the federal level.

People become seriously ill all the time. The research reviewed in this brief provides evidence that paid leave for the seriously ill and their caretakers over weeks and months can provide important health and economic benefits to individuals and to society broadly over months and years. Had a paid medical leave and paid caregiving leave social insurance program already been in place at the federal level when COVID-19 struck, the mechanics would have been in order to disburse funds to workers taking caregiving and medical leave as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.