Category: Coronavirus Recession

How the coronavirus recession is impacting part-time U.S. workers

The coronavirus recession continues to highlight and deepen the structural inequities that have long made the U.S. economy so fragile.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Employment Situation Summary—also known at the Jobs Report—the unemployment rate fell from 14.7 percent in April to 13.3 percent in May and the economy recovered 2.5 million nonfarm payroll jobs. After prime-age employment experienced the steepest decline in history in April, the share of the population aged 25 to 54 that has a job rose to 71.4 percent in May.

But the Jobs Report also shows that May’s decline in joblessness was mostly driven by White workers, whose unemployment rate went from 14.2 percent in April to 12.4 percent in May. The unemployment rate of Hispanic workers also fell, albeit less so and still standing at unprecedented levels, going from 18.9 percent to 17.6 percent. Meanwhile, the joblessness rate for Black workers actually climbed from to 16.7 percent in April to 16.8 percent in May.

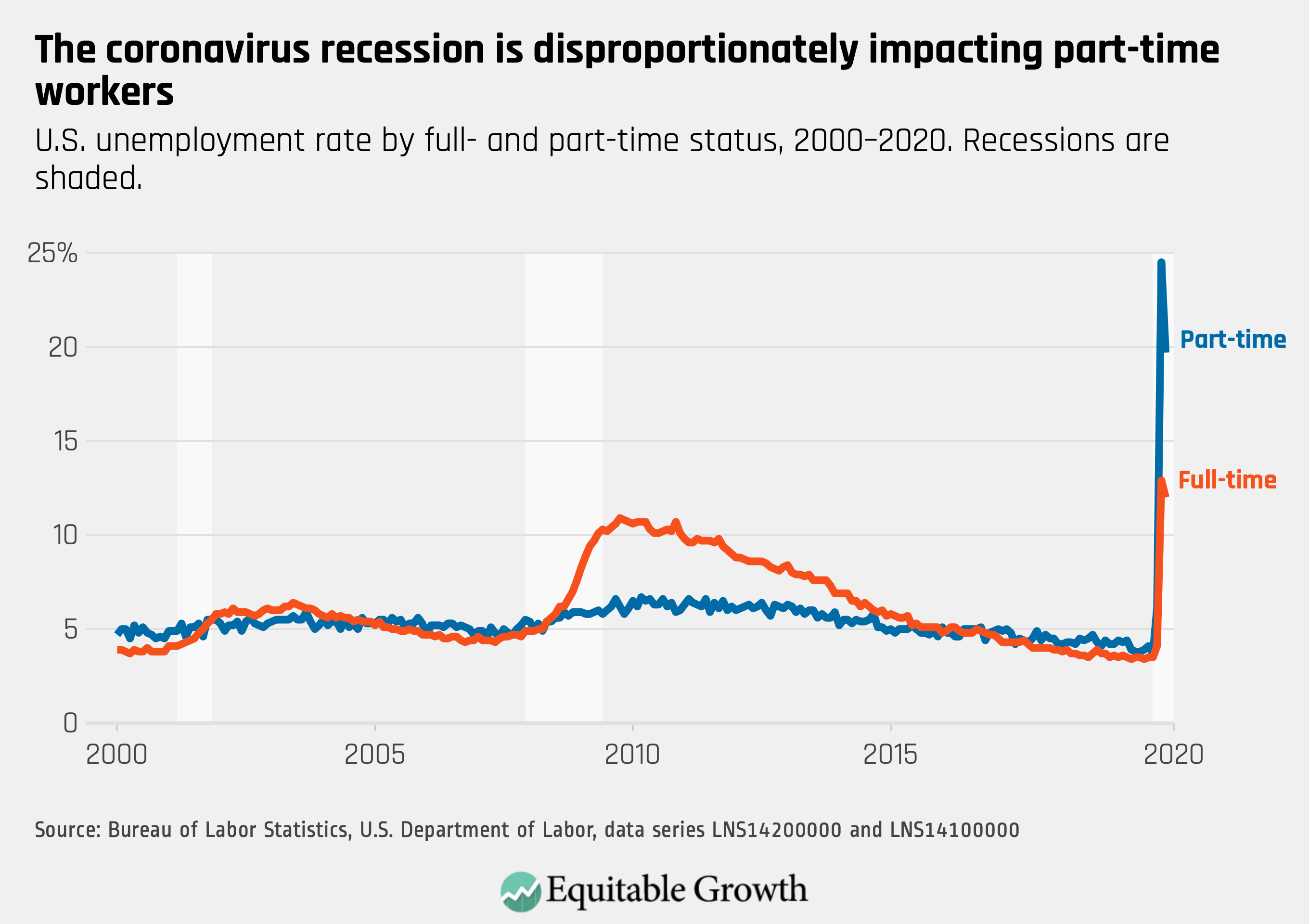

Part-time workers are also among the hardest hit by the coronavirus recession. They have accounted for almost one-third of the decline in employment since pre-pandemic February, despite making up less than one-sixth of the U.S. workforce. Between February and May, the unemployment rate of part time workers surged from 3.7 percent to 19.7 percent. The unemployment rate for full-time workers has increased at a much slower pace, going from 3.5 percent to 12 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Even before the current economic downturn, part-time workers—those working less than 35 hours per week—were already an especially vulnerable segment of the workforce. Part-time workers are disproportionately women of color, are much more likely to experience financial strain, and are much less likely to receive benefits such as paid holidays, health benefits, and family leave. For instance, even though more than 70 percent of U.S. workers have access to paid sick leave, less than half of part-time workers do.

Young workers and those 65 and older—groups that have consistently been among the hardest hit by recessions—are also overrepresented among those doing part-time jobs. This means some of the workers most affected by the current downturn are also among the least likely to have the financial resources to ride out the recession.

Even though it is not surprising that part-time workers have smaller annual and weekly earnings than their full-time peers, a new study by Lonnie Golden of Penn State University advances previous research that shows they experience an hourly wage penalty, with part-timers making 20 percent less per hour than workers with comparable levels of education, demographic characteristics, and working jobs in the same industry and occupation. This penalty is especially burdensome for Black and Hispanic women, who are also overrepresented among those who would like to work more hours but are not able to because of slack labor market conditions or because they could only find part-time jobs.

The massive 7.7 percentage point unemployment gap between part-time workers and their full-time counterparts also points to how the coronavirus recession is different from the previous downturn. In the worst months of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, full-time workers faced an unemployment rate that almost doubled that of their part-time peers. That the opposite is now true is, in part, explained by part-time workers’ overrepresentation in the service occupations being the hardest hit by the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession. Similarly, this occupational composition helps explain why part-time workers experienced a bigger decline in joblessness this month, with the leisure and hospitality industry gaining 1.2 million jobs—almost half of the employment gains between mid-April and mid-May.

Part-time workers’ unemployment toll is particularly concerning in the context of the current crisis. Many of them are taking on new caregiving responsibilities and may need positions that demand fewer hours. What’s more, part-time workers are experiencing delays and barriers to access unemployment benefits, much like what is happening to independent contractors and the self-employed. Increasing unemployment insurance through proposals included in the Heroes Act, which just passed the U.S. House of Representatives, would work as a mechanism for macroeconomic stabilization, making this recession shorter and less severe. It also would represent a step forward in alleviating long-standing disparities that have prevented many workers, and especially Black workers, from receiving benefits.

Policymakers should also help part-time workers by ensuring these positions are well-paid and secure by expanding access to basic benefits such as paid family leave and paid sick leave—benefits to which Black workers, who are also particularly impacted by recessions and left behind by recoveries, have less access to than their White peers. There should also be increased federal support for the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which has helped leveling the playing field by providing important support to families of color. In this way, the care responsibilities of many part-time workers would be more stable and sustainable.

Moving from Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation to a job losers’ stimulus program amid the coronavirus recession

Overview

The coronavirus recession is shattering businesses and dramatically increasing unemployment, which hit 14.7 percent in April 2020, the highest level since 1948.1 So far, the federal government has delivered a one-time cash stimulus to most households and increased the amount of unemployment benefits for workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own through a program called Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation. But individuals and households affected by the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession will continue to need support even after it is safe for businesses to reopen. The federal government should therefore consider allowing people who have lost their jobs to keep their expanded unemployment benefits when they go back to work for as long as they could have collected these benefits by staying unemployed.

My proposed policy, the job losers’ stimulus program, is a cash stimulus for workers who have lost their jobs regardless of whether they remain unemployed or find new employment. Compared to only providing higher unemployment benefits to the unemployed, the job losers’ stimulus program boasts the twin benefits of providing greater support to workers who have been most affected by pandemic-related job losses while also modestly increasing overall employment. The exact size of the impact of this new stimulus program is difficult to predict, but a simple policy simulation shows that it could increase the amount of stimulus by 34 percent and allow an additional 6 percent of workers to exit unemployment and return to work within 4 months of losing their jobs.

The job losers’ stimulus program would strengthen the fiscal stimulus at a critical time for economic recovery and would create jobs and raise Gross Domestic Product by increasing consumer demand.2 This is especially important as consumer demand is low during the pandemic, which already led to price decreases as of April 2020.3 Such price decreases can lead to a deflationary spiral in which businesses are cash-strapped and must lay off workers, leading to even lower consumer demand and further price decreases down the road. Beyond these macroeconomic effects, the job losers’ stimulus program also directly benefits job losers and their families: The literature shows that an unconditional cash transfer has many positive effects, in particular on children’s education and health outcomes.4

Download FileMoving from Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation to a job losers’ stimulus program amid the coronavirus recession

The job losers’ stimulus program would also have positive effects on the U.S. labor market, allowing workers to return to work when the economy can safely reopen without losing precious income. Typically, Unemployment Insurance benefits do not replace all of a worker’s lost income, but the federal move to expand benefits by $600 per week during the pandemic as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act means that some workers are receiving more in unemployment benefits than they earned while employed. Instead of taking away these important benefits from workers when the economic recovery is fragile, the job losers’ stimulus program would allow them to keep these benefits as they start working again and make more money overall than if they stayed unemployed.

Unemployment Insurance benefits are a powerful fiscal stimulus during times of low consumer demand

An increase in federal government spending during a recession can increase GDP by more than the value of that spending—in some cases, almost doubling the amount of the original stimulus. This multiplier effect occurs when consumer demand is low. In April of this year, for example, the price of clothing decreased by 4.7 percent because there was not enough demand.5 When it is safe to reopen, a cash stimulus can increase consumers’ demand for clothing and create jobs in the clothing retail industry. These extra jobs then lead to more people having higher incomes and spending on more clothes, as well as other goods and services, multiplying the impact of the original cash stimulus.

The multiplier effect for Unemployment Insurance is at least 1.7, meaning that a $100 increase in government spending leads to $70 additional GDP in the private sector.6 This 1.7 multiplier effect is based on the effect of fiscal stimulus during the Great Recession of 2007–2009. The expansion of Unemployment Insurance during the Great Recession had an even greater impact—about 1.9, which means that every $100 spent on Unemployment Insurance led to $90 additional GDP value.7

The job losers’ stimulus program would build on this success by giving additional cash to formerly unemployed workers after they find a new job or otherwise return to work. In doing so, the job losers’ stimulus increases the size of the stimulus at a time when it can have the greatest impact, and the effect of each additional dollar can be calculated using the fiscal multiplier.

Increasing Unemployment Insurance has little effect on overall employment levels during a deep recession

In a booming economy, when there are jobs to be had, increasing unemployment benefits can moderately increase the length of time workers remain unemployed. Overall, the literature shows that a 10 percent increase in benefits increases unemployment duration by 5 percent. This 0.5 elasticity is the average in the U.S. literature.8

Yet increasing unemployment benefits generally produces less of an effect on unemployment duration during a recession. The literature on Unemployment Insurance shows both theoretically and empirically that the impact of Unemployment Insurance on employment levels in a recession is smaller than in a boom.9 For instance, while more generous Unemployment Insurance can reduce job applications, this may not increase unemployment much if jobs are in short supply to begin with.10 A randomized controlled trial shows that increasing job search intensity in a depressed labor market has little effect on overall unemployment because job seekers engage in a rat race, where they are stealing jobs away from each other.11

But how small is the elasticity of unemployment with respect to unemployment benefits during the current recession? It is almost certainly smaller than the average elasticity estimated in the U.S. literature of about 0.5. Using data from the Great Recession, I have shown that the effects of Unemployment Insurance on aggregate unemployment are 40 percent smaller than the micro effects on individual behavior.12 If we apply this reduction to the 0.5 elasticity from the literature, we obtain an elasticity of 0.3.13

Because the coronavirus recession is particularly deep, the elasticity could be even less than 0.3—potentially close to zero. Indeed, a careful quasi-experimental identification strategy finds no statistically significant effect of benefit extensions on aggregate unemployment during the Great Recession.14

The job losers’ stimulus program would help newly employed workers while allowing those still unemployed to search for the right job

When Unemployment Insurance does increase the duration of unemployment, it does so for two main reasons. The first (and most commonly discussed) reason is what economists call “moral hazard,” where workers are less likely to return to work because doing so will make them lose their unemployment benefits. The other reason, called the “liquidity effect,” is that unemployment benefits give unemployed workers enough money to live on so that they can afford to wait for a reasonable job, instead of being so desperate that they must take the first job opportunity they find to avoid severe financial hardship. Research by Harvard University economist Raj Chetty shows that the effect of Unemployment Insurance on employment is about 60 percent due to the liquidity effect.15

Because the job losers’ stimulus program would ensure that workers continue to receive unemployment benefits after returning to work, it only has a liquidity effect. In other words, it removes any potential disincentive to return to work, neutralizing the moral hazard concern, but continues to support job searchers who are looking for an appropriate match.

What does this mean for the potential impact of the job losers’ stimulus? We know that the elasticity due to liquidity effects is only 60 percent of the overall elasticity of unemployment with respect to unemployment benefits. If the elasticity is 0.5 to begin with, then the liquidity effect elasticity is only 0.3, calculated as 0.50.6=0.3. If the elasticity is already only 0.3, as I argued is more realistic in this recession, then the liquidity effect elasticity is just 0.18, calculated as 0.30.6=0.18. Therefore, the effect of moving from the extra Unemployment Insurance benefit to the equivalent job losers’ stimulus removes the moral hazard effect and only maintains a liquidity effect, thereby lowering the elasticity from 0.3 to 0.18.

Putting it all together: Simulated policy impact

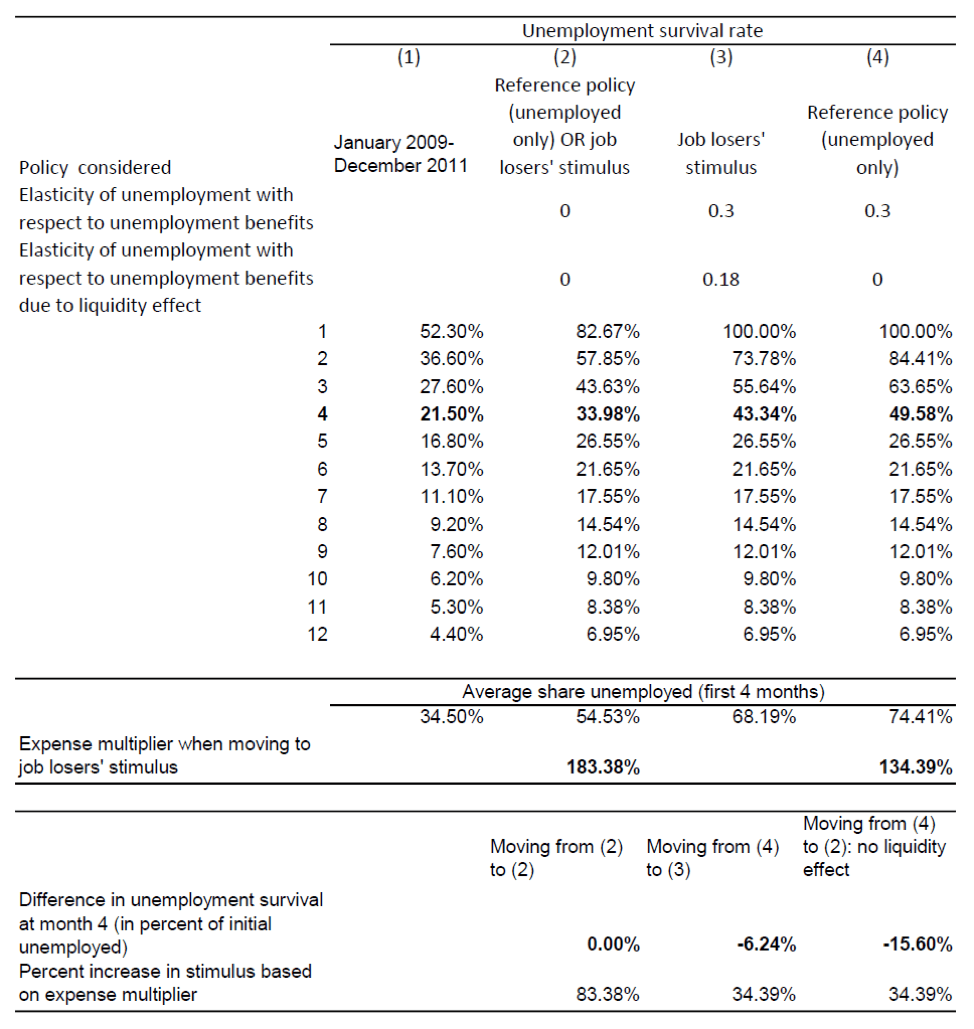

We can predict the likely impact of the job losers’ stimulus by calculating a simulation of the program if it were hypothetically implemented. To begin, we assume that the reference policy is to give a $600 weekly additional benefit to the insured unemployed only, and for up to 4 months starting at the beginning of the unemployment spell. The 4-month period was chosen because the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, or FPUC, program created by the CARES Act ends on July 31, 2020, which is 4 months after the act was passed.

To simulate the impact of the proposed job losers’ stimulus program, I examine the difference it makes relative to the reference policy I just described. The reference policy is different from the actual FPUC program because the reference policy is not limited in time; for my purposes, I will assume that a worker who loses his or her job in May can collect Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation for 4 months until September 2020 instead of having the benefit cut in July. In contrast, I assume that the job losers’ stimulus program allows all covered unemployed workers to receive $600 a week for 4 months, whether they remain unemployed or not.

I start with the unemployment survival rate that would prevail in the absence of any extra $600 weekly FPUC benefit. This allows policymakers to know, after each month of unemployment, what percent of originally unemployed people are still unemployed. To predict how the extra $600 a week for the unemployed affects unemployment duration, I apply the elasticity of unemployment with respect to unemployment benefits to the survival function for each of the first 4 months of unemployment. For simplicity, I assume that from the fifth month on, the unemployment survival function converges back to what it would have been without the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation benefit.

Next, I examine how moving from the reference policy to the job losers’ stimulus program affects the amount of stimulus and unemployment. To figure out the extra amount of stimulus, I use the elasticity-adjusted survival function calculated in the prior step. (See the Table in the Appendix.) Taking the average over the first 4 months shows the share, out of the initial job losers, who are still unemployed and receive the job losers’ stimulus benefits over the first 4 months of the spell. One minus this average gives us the share of those who are no longer unemployed and receive benefits—this is the size of the extra stimulus because the benefits are expanded to those who are no longer unemployed.

Once the increase in stimulus is known, its effect on the economy can be calculated using the fiscal multiplier discussed above.

What about the effect of the job losers’ stimulus program on unemployment? The job losers’ stimulus only has a liquidity effect and no moral hazard effect. Therefore, it’s important to compare the unemployment survival rate in the first 4 months for the reference policy, which includes both a moral hazard and a liquidity effect, to the unemployment survival rate for the job losers’ stimulus, which includes only a liquidity effect. Because the liquidity elasticity is smaller than the overall elasticity, unemployment necessarily decreases with the job losers’ stimulus, and more people return to work.

Empirically, not all workers exiting unemployment return to work. Some people will leave the labor force entirely. But as these exits usually occur later on in the unemployment spell, policymakers can reasonably assume that all those who exit unemployment in the first 4 months do so because they are returning to work.

To implement this calculation, I first take the unemployment survival function during the Great Recession. Using the Current Population Survey gives me the survival function for unemployment spells for Unemployment Insurance-eligible workers in January 2009 to December 201116; I reproduce these numbers in column 1 of Table 1 in the Appendix. During that period, the unemployment rate was, on average, 9.3 percent, using the data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve.17 In April 2020, the unemployment rate was 14.7 percent, and this is before any effects of the extra $600 weekly benefit could have reasonably increased unemployment duration. I, therefore, inflate the unemployment survival rate by an amount proportional to the ratio of the unemployment rates between the two periods.18 I reproduce the inflated unemployment survival rate in column 2 in the upper panel of Table 1 in the Appendix. I then take this survival function to be the unemployment survival function in the absence of $600 a week extra unemployment benefits, or if the elasticity of unemployment with respect to benefit levels is zero.

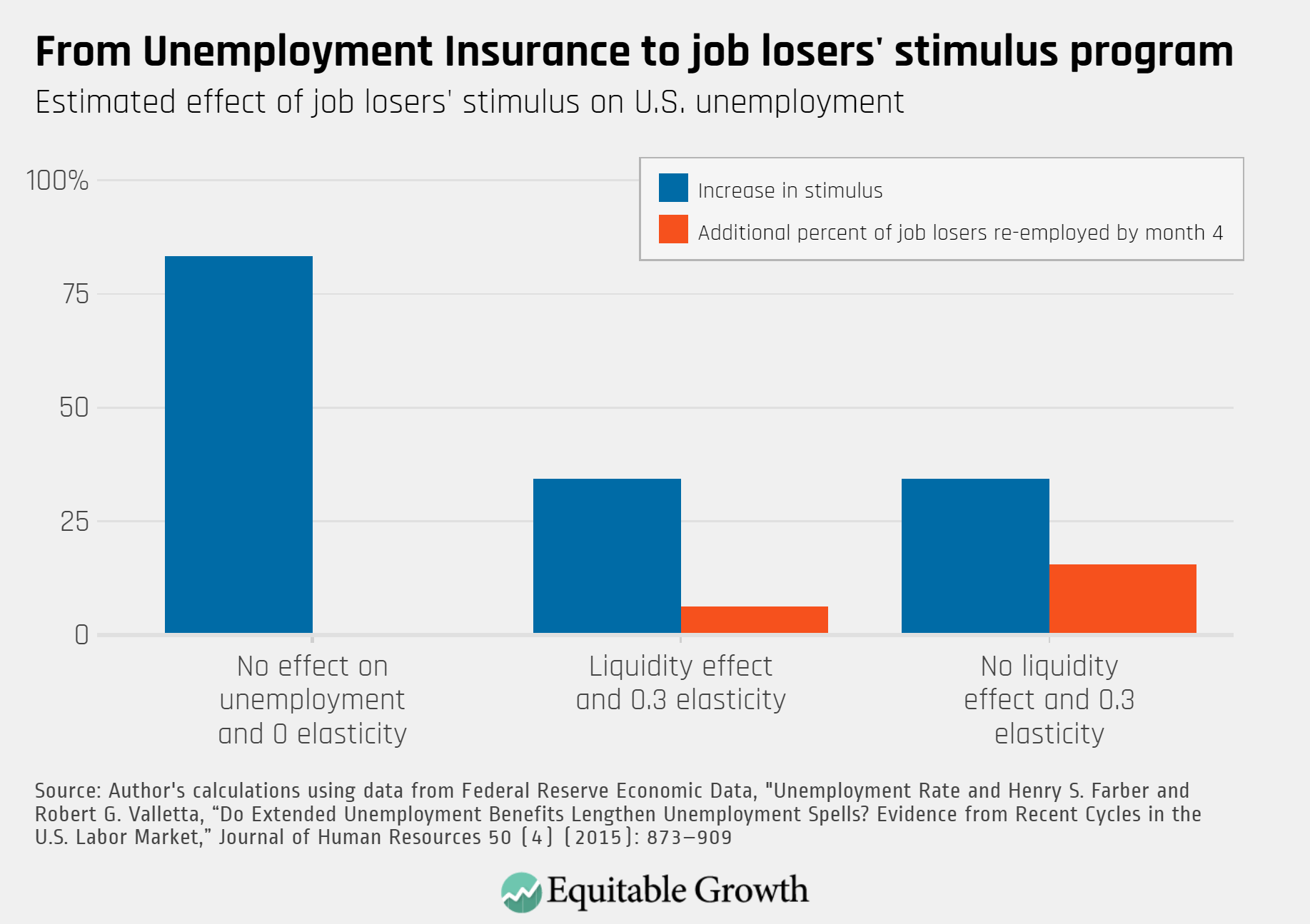

The exact size of the impact of the job losers’ stimulus is difficult to predict, but the relative size of each of these benefits follows a highly predictable pattern. If the effect of the job losers’ stimulus on unemployment is smaller, then the stimulus effect is larger, and vice versa. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Let’s look at the effect of the job losers’ stimulus through how it would affect a worker with the median annual wage of $40,000, according to Consumer Population Survey data for 2019. This median worker receives $393 in weekly unemployment benefits in a typical state such as Pennsylvania. Adding the $600 Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation benefit is an increase of 153 percent.

I then calculate the proportional increase in cash stimulus and the extra share of the initially unemployed who exit unemployment and return to work using the procedure outlined above. I consider three scenarios, summarized in Figure 1. The underlying full calculations are in Table 1 in the Appendix. Specifically:

- In the first scenario, the benefit increase has no effect on unemployment. In this case, the unemployment survival rate does not change (it stays as it is in column 2 in Table 1 in the Appendix), and the stimulus effect is maximum, with an 83 percent increase in the stimulus due to those job losers finding jobs within 4 months also receiving benefits.

- In the second scenario, the elasticity of unemployment duration with respect to benefit extensions is 0.3, and there is a liquidity effect: 60 percent of the elasticity is due to a liquidity effect, so the effective elasticity is 0.18, calculated as 0.3*0.6=0.18. In this case, the stimulus effect is lower, with a 34.39 percent increase in the stimulus. In contrast, now there is an effect on unemployment—an additional 6.24 percent of the initial job losers return to work within 4 months. (See the survival rate in month 4 in column 4 versus column 3 of Table 1 in the Appendix.)

- In the third scenario, the elasticity of unemployment duration with respect to benefit extensions is 0.3, and there is no liquidity effect—in other words, the whole of the elasticity is explained by moral hazard. In this case, the job losers’ stimulus—which removes moral hazard effects—has no effect at all, not even a liquidity effect, on unemployment duration. Therefore, the job losers’ stimulus now decreases unemployment more than in the second scenario—an additional 15.6 percent of job losers return to employment within 4 months. (See the survival rate in month 4 in column 4 versus column 2 of Table 1 in the Appendix.) The stimulus effect is the same as in scenario 2 above, a 34.39 percent increase in stimulus, because the stimulus effect only depends on the overall elasticity, not the liquidity effect.

Therefore, comparing column 2 and column 4 in Table 1 in the Appendix demonstrates that the higher the unemployment survival function is (meaning that unemployment duration is longer), the smaller the stimulus effect is because there are fewer people who are no longer unemployed and will also receive the benefits. For the same reason, a higher elasticity leads to a lower stimulus effect because a higher elasticity increases the unemployment survival rate, and so there are fewer re-employed people who can benefit.

Let’s take scenario 2 as an example to see how we can calculate the dollar amount for the stimulus effect and the number of job losers who return to work within 4 months based on our estimates. In scenario 2, the stimulus increases by 34.39 percent. The Congressional Budget Office currently projects that the extra $600 a week will cost $176 billion.19 If I take this number as the baseline, then the increase in stimulus is $61.42 billion.20 With a fiscal multiplier of 1.9, this would create an additional $55.28 billion in economic activity.21 At the same time, an additional 6.24 percent of the insured unemployed now find a job within 4 months.

Given that there were 18.9 million insured unemployed on April 18, and most of those entered unemployment in April, then an estimated 1.18 million job losers would return to work within 4 months due to the job losers’ stimulus.22

Conclusion

Overall, then, moving from the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation to the job losers’ stimulus program would provide more income to workers who lost their jobs during the coronavirus recession. It would strengthen the much-needed stimulus to the economy while also allowing more unemployed workers to return to work when it is safe to do so.

—Ioana Marinescu is an assistant professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Appendix

Table 1

Notes: In the upper panel, the unemployment survival rate in column 1 is from (Farber and Valletta 2015), Table 3. In column 2, the survival rate is multiplied by 14.7/9.3 to account for the fact that the unemployment rate was 14.7% in April 2020 vs. 9.3% in January 2009-January 2011. In column 3, the survival rate from column 2 for months 1-4 is multiplied by the elasticity 0.18 and by 153%, which is the increase in weekly benefit levels; in month 1, the survival rate is slightly above 100%, so I truncate it to 100%. In column 4, the survival rate from column 2 for months 1-4 is multiplied by the elasticity 0.3 and by 153%, which is the increase in weekly benefit levels; in month 1, the survival rate is slightly above 100%, so I truncate it to 100%.

In the middle panel, the average share unemployed in the first 4 months is the simple average of the survival rate in months 1-4. The expense multiplier when moving to job losers’ stimulus is the inverse of the average survival rate in months 1/4.

In the bottom panel, we can calculate the effect of moving from unemployment benefits to job losers’ stimulus under different assumptions as described by column headings. The 34.39% in column 3 is not a mistake but represents the fact that moving to job losers’ stimulus allows job seekers who would have been reemployed under unemployment insurance (in col. 4) to also receive the job losers’ benefit.

One year later: Recession Ready and the coronavirus recession

Proposals put forth can help support communities, stabilize the economy amid coronavirus recession

One year ago, long before the risks of the new coronavirus and the ensuing recession enveloped our nation, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, in partnership with The Hamilton Project, released Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy. This book advanced a set of evidence-based policy ideas for shortening and easing the adverse consequences of the next recession with the use of triggers that would increase aid to households and states during an economic crisis and only recede when economic conditions warranted. Experts from academia and the policy community proposed six big ideas, including two new initiatives and four improvements to existing programs.

Since the book was released, 1 in 4 Americans have lost their jobs amid the coronavirus recession, inflicting significant harm on families at a time when many are coping with the loss of friends and loved ones among the more than 100,000 who have died in just 3 months. As the new coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease spread by the virus, continue to threaten lives and our economic stability, Equitable Growth and The Hamilton Project will co-host an anniversary event on June 8 featuring:

- Heather Boushey, president & CEO of Equitable Growth

- Jason Furman of The Hamilton Project, the Harvard Kennedy School of Government, and Equitable Growth Steering Committee member

- U.S. Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA)

- Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter

- Jay Shambaugh, director of The Hamilton Project and a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution

They will discuss the significance of the policies laid out in Recession Ready and why providing aid to state and local governments is absolutely critical.

With state and local general fund revenues in freefall due to needed increases in spending on healthcare and related spending amid plummeting tax revenue, these governments’ budgets are on the precipice. State budget shortfalls could total more than $500 billion in a single year, nearly double what it was estimated states missed out on in the entire decade following the Great Recession. Fiscal requirements that states balance their budgets are already forcing governors to propose cuts in spending that will harm already struggling communities.

During the previous recession, these budget cuts proved seriously harmful to the economy. Shrinking state and local government budgets during the Great Recession reduced Gross Domestic Product by more than three times the size of the cuts themselves, according to estimates.

The proposals offered in Recession Ready are designed to help policymakers mitigate economic harm precisely at moments such as today. Though the policy proposals are focused on the federal government, which is the only entity that can deficit spend at a time of crisis, the policies themselves are designed to help individuals and families by providing support to state and local communities. They include:

- Increasing federal support for state Medicaid programs and Children’s Health Insurance Programs during economic downturns: This increased federal support would offset approximately two-thirds of state budget shortfalls. When a state’s unemployment rate exceeds a threshold level, the matching rate for these two programs would increase by 4.8 percentage points for every percentage point the state’s unemployment rate exceeded the threshold. Automatic increases in the state matching rate would reduce pressure on state budgets, reduce incentives to cut health spending when the need is large, and diminish the severity of economic downturns. As a state’s economy recovers, its matching rate would gradually and automatically phase down. A version of this trigger was proposed in Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi’s (D-CA) alternative to the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act.

- Increasing Unemployment Insurance and macroeconomic stabilization during economic downturns: Increasing Unemployment Insurance participation and payments during downturns, as well as strengthening extended unemployment benefits, would provide a backstop for workers who lost their jobs through no fault of their own and are searching for new work. Unemployment Insurance, a joint state-federal program that is administered by states, acts as a macroeconomic stabilizer during recessions by supporting the consumer expenditures of those who experience unexpected drops in income during spells of involuntary unemployment, helping pump money back into state and local economies that would otherwise be lost. Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO) released a recent proposal that would codify many of the recommendations made in this proposal, as did our upcoming event’s featured speaker Rep. Beyer, through the introduction of the Worker Relief and Security Act. The HEROES Act, which recently passed in the House, would extend the extra $600 of weekly federal unemployment benefits, which is set to expire in July, through January 2021, and includes protections for immigrants, gig workers, independent contractors, part-time workers, and self-employed people.

- Strengthening the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program as an automatic stabilizer during economic downturns: Limiting or eliminating SNAP work requirements, as well as increasing SNAP benefits by 15 percent, would increase resources available to individuals and localities in recessions. Increasing SNAP accessibility also would reduce the need for other state and local government-funded supports such as food banks. Sen. Bennet recently announced a plan drawing from this proposal, and the HEROES Act included an amendment that would increase SNAP benefits by 15 percent through September 2021.

- Providing direct stimulus payments to individuals during economic downturns: Providing direct payments that are automatically distributed when the unemployment rate increases rapidly would boost consumer spending that could help keep struggling businesses afloat. It would ease the burden on local social services as an increasing number of families struggle to afford rent and food. These direct payments would offset about half of the slowdown in consumer spending that occurs in a typical recession. A group of senators called for a similar proposal recently that would include an immediate $2,000 cash payment for every adult and child, which would decrease in amount and phase out over time as economic conditions improve. The HEROES Act proposes another round of a one-time $1,200 payment for individuals, with families of five receiving up to $6,000.

- Improving the countercyclicality of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program during economic downturns: Expanding federal support for basic assistance and creating an ongoing job subsidy program would help to reduce employment losses in state and local communities. These triggers would come with the assistance of a federal match rate in coordination with states and counties that administer the TANF program, including cash vouchers and emergency assistance to meet the basic needs of families during recessions and cover part of the cost of employers hiring and employing workers who would have not otherwise been hired into positions that would have not otherwise existed.

- Providing an automatic infrastructure investment program during economic downturns: Funding transportation projects at the state and local level through expanding the U.S. Department of Transportation’s BUILD funding would create new jobs in local communities through federal funding that typically constitutes a sizable share of state and local government spending, providing a valuable, long-lived benefit for firms and households alike.

Policymakers have already enacted more than $3 trillion in rescue measures designed to bolster public health and stabilize the economy, but more must be done. Absent further policy action, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office projects that by December 2021, the national unemployment rate will remain elevated at 8.6 percent, presenting a stunningly high cost to both individuals and families and state and local budgets. The policies outlined in Recession Ready are the best set of ideas to help policymakers avoid this devastation.

Please join the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the Hamilton Project at our joint June 8 event to hear from Boushey, Furman, Rep. Beyer, Mayor Nutter, and Shambaugh to learn more about how these proposals are essential to ensuring an equitable and broadly shared recovery.

Policy options for building resilient U.S. medical supply networks

Overview

U.S. policymakers in Congress across the political spectrum, from Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) to Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-MI) to Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), all agree that the United States is woefully underinvested in the resilience of our supply networks, especially for medical products.23 This underinvestment in the past left our nation in 2020 particularly vulnerable to the new coronavirus pandemic.

To cope with the still-rolling coronavirus public health crisis and accompanying economic recession, and then to prepare the eventual economic recovery, U.S. policymakers need to plan to rebuild the U.S. production of key medical products. They then need to act on these plans to be fully prepared for the next pandemic or other public health crises. Our recommendations are in three broad categories:

- Identify and assure stable long-term U.S. demand for key medical products, including equipment, pharmaceuticals, and the key ingredients in these products’ supply chains

- Rebuild U.S. supply capabilities by investing in new equipment, the U.S. workers who need to be trained, and the supply networks that need to be built

- Promote productive investment and good jobs in medical supply chains by empowering the agencies in charge of procuring medical supplies to protect our public health with maintaining not just stockpiles but also the resiliency of the U.S. supply chains themselves

We present a range of policy ideas in each of these broad categories that we think could work to make our medical supplies network more resilient, with emblematic examples when appropriate. We also include examples of other global manufacturing supply chains that exhibit similar strains in relation to the needs of U.S. manufacturing, as well as examples of where these fragile supply chains have become more resilient due to concerted government action.

Our first key point is that our supply chain policies work best with “high-road” investment and workforce policies that strengthen our domestic supply chains, encourage innovation in production capacity alongside the development of new technologies and drugs, train a well-paid production workforce, and ensure labor, environmental, and corporate reforms strengthen rather than weaken our domestic supply chains.

Our second key point is that a concerted national effort is required to overhaul our medical supply chains to better protect U.S. public health. To ensure the three broad steps listed above and detailed below are taken by the federal government, we propose that Congress empower the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to establish these proposed reforms to secure our medical supplies. And we suggest that the U.S. Department of Commerce take the lead in helping foster a business environment conducive to the reshoring of these key parts of these supply chains.

With these broad objectives in mind, and with this broad outline of where in the federal government these comprehensive objectives should be implemented, let’s examine each of the three categories in turn.

Download FilePolicy options for building resilient U.S. medical supply networks

Identify and assure stable long-term demand

Without stable long-term demand, no company will invest in building up production capacity and workers, managers and investors will not invest in the necessary skills. To achieve long-term rebuilding of our production capabilities all economic actors need to know that an elevated level of demand for domestically produced products and components is here to stay. In the medical supplies arena, the federal government should be the core provider of stable long-term demand as a public health priority.

Without this stable demand, government funding to build up supply will not be effective in maintaining resilient U.S. supply chains. Indeed, many new technologies invented in the United States using federal funding are alas no longer manufactured here in any great quantities. These include storage drives, lithium-ion batteries, liquid crystal displays, and many medical goods.24 That’s why government purchasing at the federal, state, and local level should have a “Made in America” component as part of a core national supply chain strategy. Here are several proposals to do so.

Coronavirus relief funding to medical supply companies and the Strategic National Stockpile

Companies involved in providing medical supplies to the U.S. healthcare industry that are given federal aid as part of the response to the coronavirus recession should be required to move a significant percentage of their sourcing and production back to the United States. This should be done in both outright procurement programs at all levels—local, state, and federal—as well as in authorizing reimbursement programs, such as Medicaid.

The Strategic National Stockpile could be another source of demand. Implementing “Made in America” requirements does not necessarily mean abrogating our obligations under World Trade Organization rules and regulations. The WTO Government Procurement Agreement prohibits local content requirements for certain negotiated types of procurement, but these prohibitions are merely “annexes” to the main accord, meaning that according to some interpretations, breaking them wouldn’t necessarily violate the main treaty itself.25

These contracts with “Made in America” clauses should be for several years. Otherwise, firms would invest in fixed costs to build capability but would not have a chance to amortize these investments over time. That is, these expenses would hit their bottom line immediately, leading to a negative profit and loss without sparking long-term investments. Accordingly, without secured long-term contracts, it wouldn’t make financial sense for any company to make the needed capital investment.

Rebuild supply capabilities

Just expanding demand by itself will not instantly create a domestic supply. Firms need to invest in new equipment, workers need to be trained, and supply networks need to be built. There are many market failures in this process, and government should assist in solving them. Here are some policy ideas to spur this process.

Disclose supply network sources

It is hard to prevent vulnerabilities without knowing where they are. There are several ways that policymakers could encourage or require companies to do this. For critical medical products, Congress could require companies to disclose their supply chains, as proposed in the Strengthening America’s Supply Chain and National Security Act.26 This proposed law is tightly focused on pharmaceutical products. Congress should consider expanding the requirement to other products critical for domestic security as revealed by the current coronavirus pandemic, from medical devices to information technology, material science, and natural resources.

Congress then should tighten enforcement of “Buy American” executive orders and similar requirements, given the numerous waivers, exceptions, and loopholes that allow the federal, state, and local governments to purchase foreign goods without penalty. Currently, five big exceptions mean that the order is more declarative than actual.27 Better information can by itself be effective, as well as serve as a powerful peer-pressure mechanism—who wants to be known as the last CEO to reshore critical U.S. medical supplies? Companies are currently required to disclose any material threats to their businesses, but most have not interpreted pandemics as such a threat. That must change. Congress should mandate that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission require companies to publicly disclose their exposure to risks caused by public health events that the World Health Organization classifies as pandemics.

Build real options that allow production to surge

Experts and policymakers can be sure that there will be future crises, unfortunately, but they can’t know the exact future dimensions of any crisis. That’s why the federal government should stockpile some likely items in advance, such as personal protective equipment and ventilators. Concurrently, the federal government needs to mandate the building and maintenance of production capabilities flexible enough to provide what turns out to be needed. There are several ways to do this.

Increase surge capacity

Companies need incentives to maintain slack for use in an emergency since this capacity may seem to be inefficient during normal times. This slack includes buying more general equipment than companies otherwise might, planning for flexible instead of fixed production lines, maintaining the in-house capability to reprogram these production lines, and training workers more extensively so they can help design and carry out the new tasks that turn out to be necessary.28

To ensure this added production capacity is ready in a crisis, the federal government could reimburse companies for the extra expenses involved in buying and maintaining this equipment. And the appropriate federal agencies could conduct periodic drills to test compliance. An unintended benefit of the U.S. and Canadian rescue of their auto industries from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 was to maintain organizational capability. Even though personal protective equipment and ventilator production is quite different from automotive manufacturing, when General Motors Corp. and Ford Motor Company began producing PPE and ventilators to help combat the new coronavirus pandemic, they were able to use their engineering and supply chain capabilities to set up production lines and quickly identify suppliers of parts and equipment; their broadly trained production workers were quickly able to learn the new jobs.

Match demand and supply

Sometimes firms use foreign sources because they are not aware of domestic sources. Apple Inc., for example, abandoned its attempt to assemble the Mac Pro in Texas in part because it couldn’t find a reliable local manufacturer of a tiny screw needed for the Mac.29 If the company had looked beyond Texas—say, to the Midwest—it might have been able to find a domestic source for this component.

Government at the federal, state, and local levels can mitigate these deficiencies by helping firms locate domestic suppliers. Several small programs run by federal government agencies have helped firms locate domestic suppliers. The U.S. Departments of Energy and Transportation have teamed up with the Manufacturing Extension Partnership to find domestic suppliers for firms who had requested waivers from “Buy America” policies.30 Or take a page from the states of Mississippi and Pennsylvania: Each looked at detailed data on components imported from abroad into their states and then introduced the firms importing the components to domestic suppliers of similar products.31 These programs should be expanded.

Aggregate and stabilize demand

Another issue is aggregating and stablizing demand. A key issue in the Apple case mentioned above was that before Apple decided to reshore, U.S. suppliers responded to the dramatic decline in demand for their products by selling their high-volume manufacturing equipment to China. Governments at all levels in the United States also can help match supply and demand for specialized assets and skills by convening supply chain players to develop a roadmap for products ripe for reshoring. The federal government could help by supporting and funding supply chain mapping across the medical supplies network.

China, especially Guangdong province and its leading municipalities, are world leaders in those policy efforts, and we should do well to learn from them how to continuously map product supply networks, identify critical local gaps, and devise and implement actions to close them. In the uninterupted power supply, or UPS, industry in Guangdong’s Dongguan prefecture, for example, local township officials have worked hand in hand with the local industry to ensure that there are local suppliers for up to 90 percent of the components needed for a high-end UPS system. A leading official in one of Dongguan’s townships concisely described this development strategy:

The leading company is located here because of the complete production and supplier networks we have here. It is not that we have only the final UPS companies. We have all the specialized suppliers they need. For example, there is a coordinating supplier in Tangxia that supplies all three leading UPS manufacturers. So long as we have a complete industry set there is no reason more UPS manufacturers won’t come, and no reason for these that are here to move away.32

Eliminate hidden subsidies for offshoring

There are currently multiple hidden incentives for companies to offshore. Chief among them are companies engaging in regulatory arbitrage. One case in point in the pharmaceuticals industry is the current practice by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to preannounce foreign plant inspections, giving them a regulatory advantage over domestic plants, where inspections are unannounced. The FDA should have at least as rigorous an inspection program at foreign plants as it does at domestic plants.33

Another way to rebuild supply capabilities is to improve methods of purchasing medical supplies in the United States. Too often, firms and governments simply buy products that have the lowest unit costs, ignoring the possibility that the resulting supply chains might have hidden costs, such as lack of robustness or inability to innovate.34 The federal government should set up a Manufacturing USA Institute, perhaps hosted at the U.S. Department of Commerce, to research and improve methods of supply network sourcing and collaboration. These new methods could help ensure the diffusion of technologies developed at the other institutes, since these technologies are likely to be perceived as more expensive initially—unless prospective customers have methods to value the improved contribution these products will make.

The Manufacturing Extension Partnership, an existing federal program, could be used to improve medical supply chain production capabilities. Most small manufacturers supply larger firms, yet many of them struggle to adopt innovative practices due both to lack of economies of scale and poor purchasing practices such as those mentioned above. The Manufacturing Extension Partnership could help by working with lead firms to upgrade their suppliers’ capabilities.35 The MEP program is effective but pitifully small. In fiscal year 2020 ending on September 30, Congress provided funding of only $146 million—and, at the urging of Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, the president has requested it receive zero funding for FY2021.36

Akin to this manufacturing program are the “defense manufacturing communities” organized by the U.S. Department of Defense to ensure domestic production of key defense products and technologies. These communities “make long-term investments in critical skills, facilities, research and development, and small business support in order to strengthen the national security innovation base by designing and supporting consortiums as defense manufacturing communities.” This blueprint could be applied to other products, including medical products manufacturing organized by the U.S. Economic Development Agency within the U.S. Department of Commerce.37 A new bipartisan bill, the Endless Frontiers Act, introduced by Sens. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Todd Young (R-IN), proposes to do just that.38

Protect U.S. infant industries and secure their supply chains in the country

The last, but by no means least, important recommendation is for policymakers to craft legislation to protect infant industries in the United States. The United States currently runs a large trade deficit in even its most advanced technologies because start-up companies invented within U.S. universities often move abroad almost as soon as they have viable prototypes of their new technologies.

This is especially critical in cases where both new production technologies and new products that are based on them are developed. Too many times, infant U.S. companies find that they are unable to perfect the new production technologies in the United States and instead “dumb down” their products, so they can be produced using the old technologies and, hence, offshored to China. An interesting, and sadly only too common, example is optoelectronics, where, between 2010 to 2013, due to the inability of financing fabrication facilities utilizing the new integrated production methods, the United States lost a 10-year lead to the Chinese.39

Policy reforms that would allow for the building of shared production assets could allow new inventions that include U.S. production upgrades to jump over this valley of death. Knowing the availability of infant industry protection measures, by itself, will change the investment and development rationale of entrepreneurs and their financiers.40 And once one company opens the first state-of-the-art production facility in the United States and develops a resilient supply chain with sufficient U.S. domestic sourcing, the costs for its followers will be significantly lower because of economies of scale, learning, and downward sloping cost curves.

Further, since the new facilities in the United States will be built to scale using the latest technology, their yield and productivity will be second to none. And with American ingenuity to follow, unit costs will continue to come down. One historical example of this strategy in action is the production of bombers in the United States during World War II, where one study finds that “every doubling of cumulative output gives rise to 27.9 percent decline in the unit direct labor hours.”41 A similar approach to the national security threats posed by the coronavirus pandemic could well yield similar results.

Promote productive investment and good jobs in medical supply chains

The proposals presented above would work best in partnership with firms organized around productive investment and skilled, well-paid workers. Uncertainty about future pandemics and other potential disasters makes even more valuable the ability to innovate and rapidly shift to new products in the United States. Firms that focus on long-term investments in their workers and in new equipment and ways of working offer a better return on taxpayers’ investment than do firms that focus on short-term financial metrics and rewarding top executives.42

Past U.S. policies unfortunately produced counterexamples, such as contracts to produce ventilators that did not yield ventilators available to U.S. hospitals, due to anticompetitive behavior by the largest corporations. Case in point: One small company, Newport Medical Instruments, which received a contract to manufacture ventilators, was bought by Covidien, and Covidien was bought, in turn, by Medtronic PLC, which made competing products and so stalled the U.S. government contract.43

Similarly, U.S. firms have spent so much on stock buybacks that they had little cushion to weather a crisis.44 By 2019, stock buybacks reached $1 trillion and have become so prevalent that there is no sector in which their size did not dwarf their productive investment. Thus, stock buybacks have now become a significant vulnerability and obstacle to reshoring U.S. production.45

On the labor side of the equation, too, there is need for reform. U.S. workers are nearly always left out of such key decision-making at corporations about the location of the production of medical products—and now, about the priority given to providing them access to personal protective equipment—in contrast to their European counterparts. Thus, it is germane to give workers a say in not just coronavirus-related decision-making at their companies, but also supply chain decisions through mandated works councils and elected health and safety committees.46

An effective way to deal with many of these issues is the one pioneered in Israel by the Israeli Innovation Authority (formerly the Office of the Chief Scientist). This agency stipulates that any intellectual property generated by the nation’s IIA grants, which are given to R&D projects aiming to come up with new exportable products in all sectors of the economy, is not allowed to leave the country without paying a hefty fine (six times the amount of the grant). This measure, in effect, ensures that production commences in Israel, even if the grantee is a fully owned subsidiary of a foreign multinational corporation.47

Corporate governance is another key area in need of reform to promote productive investments and jobs, not just in the medical supplies arena but across the broader U.S. economy too. Our ideas presented above would be much more effective if implemented along with some broader reforms. In the past, much taxpayer money has been siphoned off by shareholders and top management of firms rather than being used for productive investment or paying worker salaries. Thus, limits on the financialization of firms and measures to empower workers as productive stakeholders can ensure effective use of citizens’ dollars.

We would thus suggest policies such as these for firms that receive government aid to help improve the resiliency of their supply chains:

- Limits on stock buybacks and executive compensation

- Establishment of works councils in large firms and elected health and safety committees

- Renewed antitrust enforcement

- Pledges of neutrality in union elections at government contractors

- Requiring government contractors to obey laws, including labor laws

Conclusion

The still-deepening coronavirus recession brutally exposes our national weaknesses. The task in front of policymakers is difficult and will take years to bear fruit. Yet policymakers can help power an economic recovery and ensure that the next crisis will not find our nation so vulnerable. The federal government can do so by enacting policies that spark new sources of demand for medical supplies, create new domestic sources of supply for those medical supplies, launch workforce training to ensure well-trained workers are available, and enforce equitable labor, environmental, and corporate reforms. A national effort is needed.

Collective national action can make the difference because a crisis of this magnitude requires government action. It is time for the federal government to invest in American ingenuity and give U.S. workers the chance to show the world what its people are capable of making, innovating, and producing.

—David Adler is co-editor of the anthology “The Productivity Puzzle” published by the CFA Institute Research Foundation and the author of related works. Dan Breznitz is the Munk Chair of innovation studies and the co-director of the Innovation Policy Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs & Public Policy and Political Science at the University of Toronto. Susan Helper is is the Frank Tracy Carlton Professor of economics at the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University. Breznitz and Helper also are co-directors of Canada-based CIFAR’s Innovation Equity and the Future of Prosperity Program.

Coronavirus recession: How to get the U.S. economy back on track

Equitable Growth launches new lecture series with inaugural event featuring Claudia Sahm on the economic crisis

Amid our nation’s health and economic crises, government officials must do more. They must use research and evidence-based polices to support people today and strengthen our economic future. The Washington Center for Equitable Growth is dedicated to promoting research that elevates effective and inclusive policies. Our new lecture series will highlight the latest economic research in order to provide policymakers with evidence-backed solutions to advance sustainable, broad-based growth.

Our first lecture in the series on May 19 was online. Claudia Sahm, who joined Equitable Growth 6 months ago as the director of macroeconomic policy, inaugurated this lecture series. Heather Boushey, Equitable Growth’s president & CEO, highlighted Sahm’s experience as a macroeconomic forecaster and researcher at the Federal Reserve and an economic advisor for the Obama administration during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and the slow recovery that followed.

Sahm, a leading expert on macroeconomic policy who has consulted members of Congress on the response to the coronavirus recession, argued for additional economic relief to households during these unprecedented public health and economic crises. She began her talk with a sobering comparison of today with the Great Depression of the 1930s. Sahm also compared today’s recession to “a Category 5 hurricane that hit the entire United States for more than 2 months.” From her research during her tenure at the Fed, she knows the damage natural disasters cause for families, businesses, and communities. Today’s epidemic is no different.

Sahm urged policymakers to “listen to experts on health and safety.” It is the only way to save lives and stop the economic freefall. She argued that it would take years to recover from this downturn absent bold intervention from policymakers. The policy actions Congress and the administration take today could save us from the worst long-term costs.

In addition, her presentation highlighted the disproportionate harm that will be borne by our most vulnerable families, businesses, and municipalities, and its severe impact on groups that were already falling behind even before the coronavirus recession. Sahm stressed, on the policy outlook, that “We don’t fight recessions forever. There are structural inequalities in the economy that we should fight forever,” adding that relief efforts must be sustained as long as there’s high unemployment.

Her presentation referenced the wealth of research evidence in Recession Ready, which was published 1 year ago to promote automatic fiscal spending triggered by proven signs of an oncoming recession. The smart solutions championed in research sponsored by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the Hamilton Project focus on stabilizing the economy through financial support to families, small businesses, and communities. These approaches have made an impact, with policymakers increasingly consulting Recession Ready authors on the best structure of future fiscal support. The book features Sahm’s own proposal to boost consumer spending during recessions by creating a system of direct stimulus payments to individuals that would be automatically distributed when the unemployment rate increases rapidly. She also previewed forthcoming work with Joel Shapiro and Matthew Slemrod at the University of Michigan analyzing new data on the 2020 rebates.

Questions on the role of the Fed and deficit spending

The presentation was followed by a conversation with Boushey and a Q&A session with the audience, which largely centered on the proper role of fiscal policy and monetary policy in protecting workers and their families. Sahm expressed optimism that the Federal Reserve learned from the Great Recession that recovery efforts need to continue for a sustained period until the economy sufficiently rebounds, but seemed skeptical whether Congress internalized the same lesson. With that said, she cautioned on leveraging the Federal Reserve’s powers to intervene more directly to start “backstopping Main Street” and lending to discreet municipalities and businesses, at the risk of exceeding its lender-of-last-resort role as authorized by Congress.

In response to concerns about the deficit, Sahm also pushed back against calls for fiscal restraint, which she warned would only serve to prolong the recession. “Recessions are times when you spend,” Sahm declared, noting how runaway inflation and crowding out of private investment did not materialize, neither as a result of the government’s fiscal response to the Great Recession, nor from extraordinarily low interest rates that continue today.

The audience also inquired about how to balance concerns about targeting relief to the most vulnerable households and businesses versus providing universal economic relief. Sahm emphasized the size of relief to be commiserate to the gravity of the crisis. She also stressed the importance of thinking long term and honoring the dignity of work to make the case for public investment in critical infrastructure, particularly in areas of the country subject to historic disinvestment.

Research provides the roadmap to recovery

The driving ethos of our first lecture in this series was the essential role of strong research evidence in crafting sound economic policy. Equitable Growth continues to fund and elevate scholarship that seeks to understand the role of macroeconomic policies in the long-term stability of the economy and its growth potential.

This first lecture underscored how research is providing a roadmap for robust federal actions to address the underlying issues of economic inequality, which has made our economy more fragile in the face of the coronavirus shock. Sahm’s presentation made clear that the unprecedented scale and speed of this challenge necessitates rapid, sustained, and bold measures to fully address the health crisis for people and families, and move swiftly into economic stabilization, recovery, and long-term resiliency that creates the conditions for broad-based growth.

Green stimulus, not dirty bailouts, is the smart investment strategy during the coronavirus recession

Overview

In March, the federal government passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security bill, more commonly known as the CARES Act. The law aims to provide relief for businesses and Americans struggling due to the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting economic recession. It also had the potential to accelerate the fight against another crisis—climate change—by funding a green stimulus to accelerate the clean energy transition.

Download FileGreen stimulus, not dirty bailouts, is the smart investment strategy during the coronavirus recession

The coronavirus and climate change are, unfortunately, linked. Air pollution from dirty energy infrastructure makes people much more likely to die from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. And those dying in the United States are more likely to be people of color, perhaps in part because of environmental injustices that expose communities of color to much higher pollution levels.

We do not have to use dirty energy that damages peoples’ lungs to power our societies. The CARES Act could have helped protect Americans’ health during this pandemic by moving us away from polluting fossil fuels. Yet rather than supporting clean energy, the law is being used to bail out the dirty fossil fuel sector.

If we continue along this terrible path, the accelerating climate crisis will disrupt employment, cause property damage, and destabilize the financial system. Why use the rescue programs from the current crisis to subsidize the industry most likely to cause the next one?

This issue brief examines how the CARES Act was deliberately misapplied to the fossil fuel industry, which was already on the ropes before the coronavirus recession. We also examine how future stimulus funds could be targeted toward clean energy, which would create more and better-paying jobs to power our economic recovery. This approach would not just help us tackle the coronavirus recession, but the climate crisis as well.

The fossil fuel industry was in crisis before the coronavirus hit

Many fossil fuel companies were already struggling before this economic crisis. Since President Donald Trump entered the White House, 11 coal companies have declared bankruptcy. To try to buck this trend, the Trump administration has found creative new ways to distort power markets to advantage coal.

Similarly, shale gas and oil companies have been struggling under high debt levels and underperforming investments. The massive global petroleum glut has only added to their woes. These hard times led carbon-intensive companies to seek refuge in bailouts when the coronavirus recession hit.

Unfortunately, the CARES Act is funding corporate welfare for polluters. The law allows the Federal Reserve to lend money to companies. In theory, these companies should be doing well enough that they are able to pay the government back. But for oil and gas companies, this may not be the case. Given very low oil prices, these companies do not have a clear pathway toward profit. Many are highly leveraged and were already struggling with credit-rating downgrades by the end of 2019. This debt burden would have initially made many oil and gas companies ineligible to receive Federal Reserve loans.

Yet after taking comments, including from the fossil fuel industry, the Federal Reserve watered down their requirements for lending. Oil and gas companies, even with their pre-existing debt, have become newly eligible. In addition, the maximum lending amount was raised from $150 million to $200 million.

Notably, U.S. Secretary of Energy Dan Brouillette said in mid-April that lending would need to be “closer to $200 or $250” million to help the fossil fuel sector, after he met with representatives from the industry. While the Trump administration has been meeting regularly with fossil fuel groups, it has not done the same for the renewable energy industry.

Some commentators have called for federal government ownership or equity stakes to be a conditional requirement for lending to the oil and gas industry, even though the CARES Act prohibits the federal government from exercising any voting power if a government financial investment takes the form of an equity stake. This clause needs to be amended to enable the federal government to influence these corporations, ideally helping to put them on a path toward reducing their fossil fuel extraction and carbon emissions. The Trump administration, however, has clarified that it has no intention of taking ownership stakes in fossil fuel companies.

Instead, fossil fuel companies have been using the coronavirus recession to try to secure immunity against lawsuits for their decades promoting climate denial. In response, 60 members of the U.S. House of Representatives recently wrote a letter opposing liability relief. These disturbing developments are not just happening federally. Across the country, fossil fuel companies and state and local governments are using this crisis as an opportunity to weaken environmental regulations.

What’s more, publicly traded coal companies have received more than $31 million as part of the law’s Paycheck Protection Program, which is designed to go to small businesses, not publicly traded companies capable of other ways of raising cash. The coal industry was initially left out of the package but successfully persuaded the Trump administration to list it as essential. Similarly, Marathon Petroleum Corporation has received more than $400 million from the CARES Act.

Environmentalists have criticized these loans as throwing good money after bad because the coal industry was already struggling financially in recent years. They’re right. These are bad economic investments. Bailing out fossil fuel industries will not yield as many jobs as investing in clean energy would.

A green stimulus can lead an economic recovery

Every dollar spent propping up a dying industry is a dollar that can’t be invested into new careers, training, opportunity, and equitable growth in the clean energy sector. Increasingly, even banks recognize this, as more and more are pulling out of fossil fuel investments that are yielding poor returns.

According to recent research from Heidi Garrett-Peltier, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, for every $1 million invested in renewable energy or energy efficiency, almost three times as many jobs are created than if the same money were invested in fossil fuels. Investing more money in the fossil fuel industry will not address high and growing unemployment rates. Indeed, the Federal Reserve is not even requiring companies to keep workers as a condition for getting loans.

The seeds of an even more pernicious argument are already sprouting. Some conservative members of Congress are raising concerns about rising federal debt levels and threatening to stop further spending on relief amid the still-deepening recession. This would be the worst of both worlds. With $1.8 trillion in direct spending, the CARES Act is larger than Vice President Joe Biden’s 10-year climate plan. Clearly, the United States is able to spend more money addressing climate change if we treat it as the crisis it is.

We need green stimulus investments because it’s a smart way to spend money. Investments in the clean economy will provide significant returns. As Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argues, alongside other colleagues, renewable energy and energy efficiency investments typically have high multipliers, delivering even greater returns over time. They also create more jobs, including ones that can’t be taken offshore, such as those in home energy retrofits.

At the end of 2019, Congress had an opportunity to put extensions for basic supports of the green energy sector into place, among them the Investment Tax Credit and the Production Tax Credit, in the year-end budget bill. But Congress decided against it. Congress then could have put these extensions in the CARES Act, but both President Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) opposed it.

This lack of support immediately before and during the coronavirus recession leaves the the renewable energy sector struggling. This quarter, for example, residential solar installations are likely to fall by half. In March alone, the clean energy industry lost more than 100,000 jobs. In wind energy alone, $43 billion in investments are at risk. Despite the terrible state the industry finds itself in, Congress is doing very little to support clean energy jobs.

Conclusion

Despite a complete economic shutdown, global carbon pollution has only declined 5.5 percent so far this year. It may fall as much as 8 percent by year end, marking the largest annual decline on record. But to limit global warming to 1.5 °C (2.7°F), emissions must fall by that amount every year for the next decade. This will not happen without concerted government policy.

Instead, U.S. policymakers could power an economic rebound and prepare to meaningfully address climate change by investing stimulus funds in the renewable energy sector. If the Great Recession of 2007–2009 is any indication, temporary emissions reductions from economic contractions quickly reverse themselves. We should learn a lesson from the previous recession and the current one—ignoring a crisis does not make it go away, be it the coronavirus pandemic or the growing climate threat.

Leah C. Stokes is an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Her recent book, Short Circuiting Policy, examines the clean energy transition.

Matto Mildenberger is an assistant professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His recent book, Carbon Captured, examines carbon pricing and climate policy.

Data will provide accountability to ensure the U.S. economic recovery is shared broadly

The U.S. economy is a long way from experiencing a recovery from the coronavirus recession. But the actions Congress takes now will determine just how deep the recession gets and how difficult it will be to pull back from the brink once the health threat has passed. So, it’s not too early to start thinking about what the recovery should look like. As policymakers start to think about recovery policy, they should target those who were most hurt by the recession. This may seem like an obvious point, but it is often overlooked because there is not usually a careful accounting of who has been harmed in economic downturns.

That is poised to change with the release of a new data series from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis that divides up annual income growth to reflect the fortunes of low-, middle-, and high-income Americans. This new dataset lets policymakers see how previous economic expansions and contractions have treated these groups differently. It is an important step toward being able to craft policy responses to recessions that target weakened groups and help them recover to their pre-recession incomes. The proposed Measuring Real Income Growth Act of 2019 directs the agency to regularly produce these statistics and gives them the resources they need to do so.

House Democrats have wisely included this bill as part of their next coronavirus response legislation. Democrats are right to do so as part of their response to the economic crisis. Following the economic experiences of different groups of Americans provides important accountability to any legislation that is passed to lessen the impact of the recession or to help Americans recover more equitably in the wake of it.

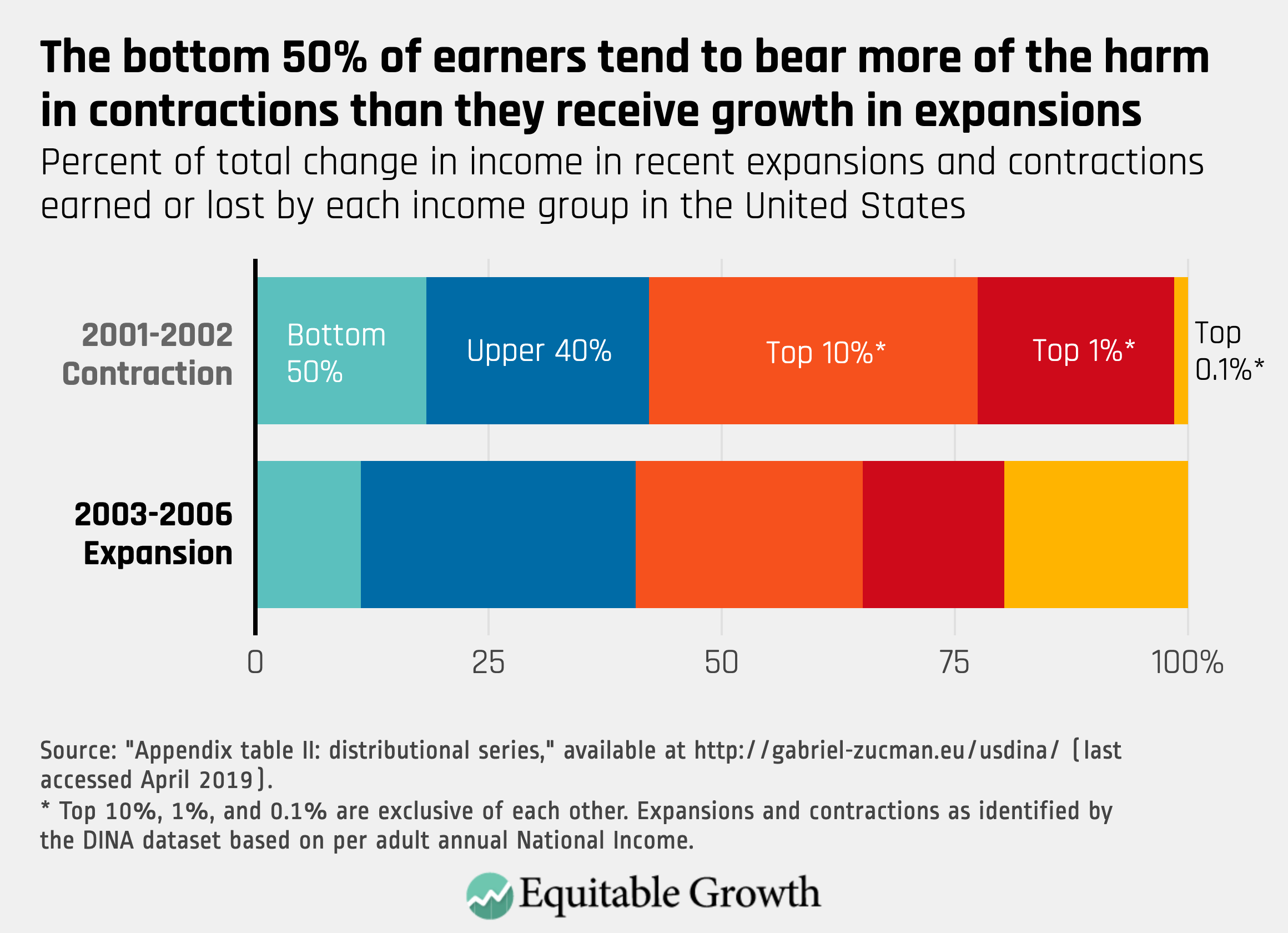

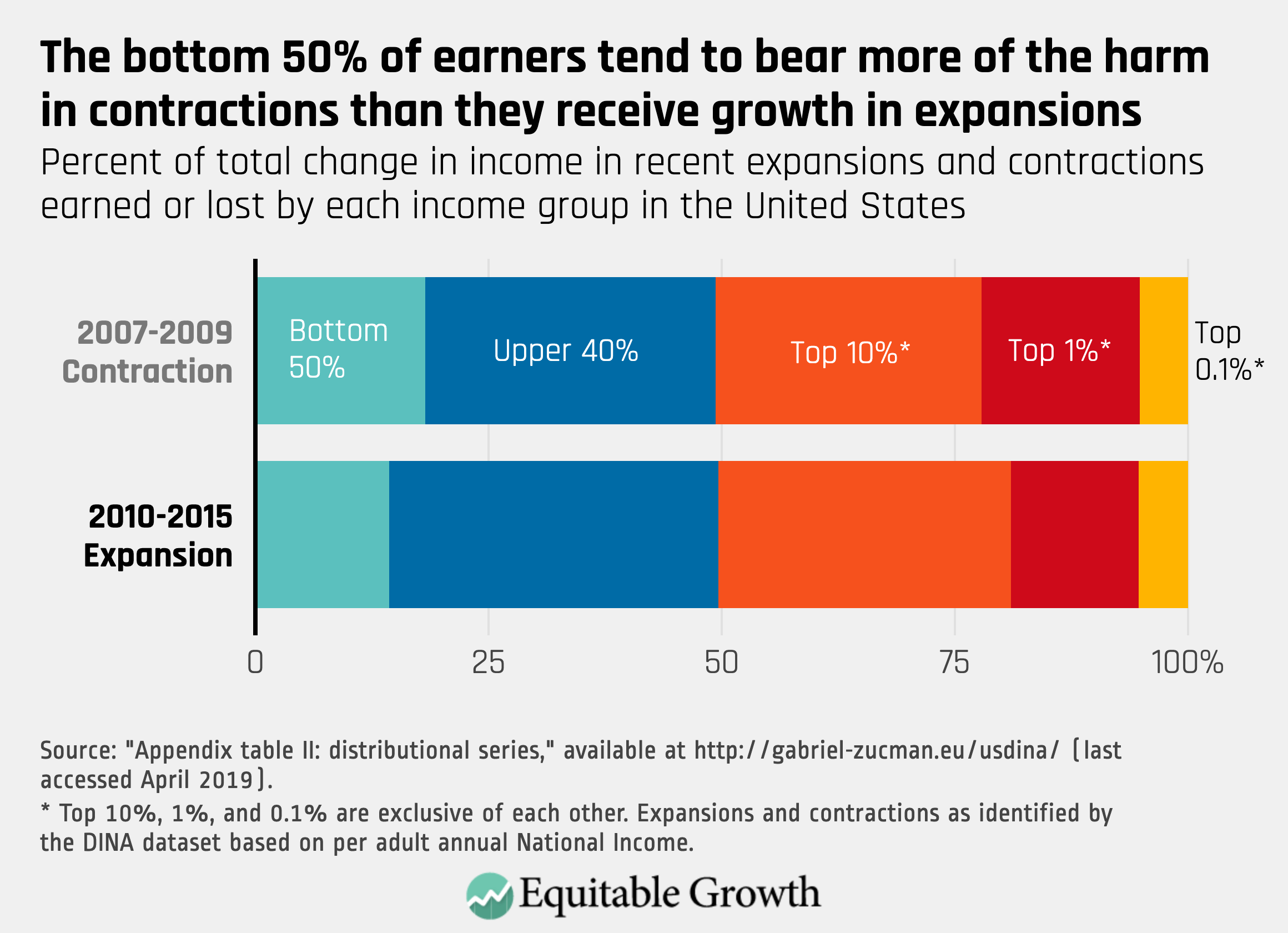

In previous economic cycles, those at the bottom have experienced far less of the gains during economic recoveries. Using the income data series created by Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley, we can see how people at different levels of income fared in the past two economic contractions and expansions. In the relatively mild contraction of the early 2000s, the bottom 50 percent of income earners bore about 18 percent of the decline in economic output. But in the ensuing expansion, from 2003 to 2006, they received only 11.3 percent of the expansion’s growth. Expansions and contractions are measured here by years of positive or negative growth according to per capita National Income, the measure favored by Saez and Zucman. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

At the same time, those at the top of the income distribution saw most of the declines during the recession but also more of the gains. Thus, when all is said and done, those at the top end up in a stronger position after a recession and recovery than they were in before. This was not only the case for the 2001 recession, but also for the Great Recession—and certainly is a concern now, especially as early indications are that those with the lowest wages have been laid off more frequently relative to higher-paid workers.

During the Great Recession, those in the bottom half of the U.S. economy had a similar, although slightly less dramatic, experience. About 18 percent of the decline in output was thanks to declines in income for the bottom 50 percent. In the following expansion, they captured about 14 percent of total income growth, through 2015, the last year of the data series. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

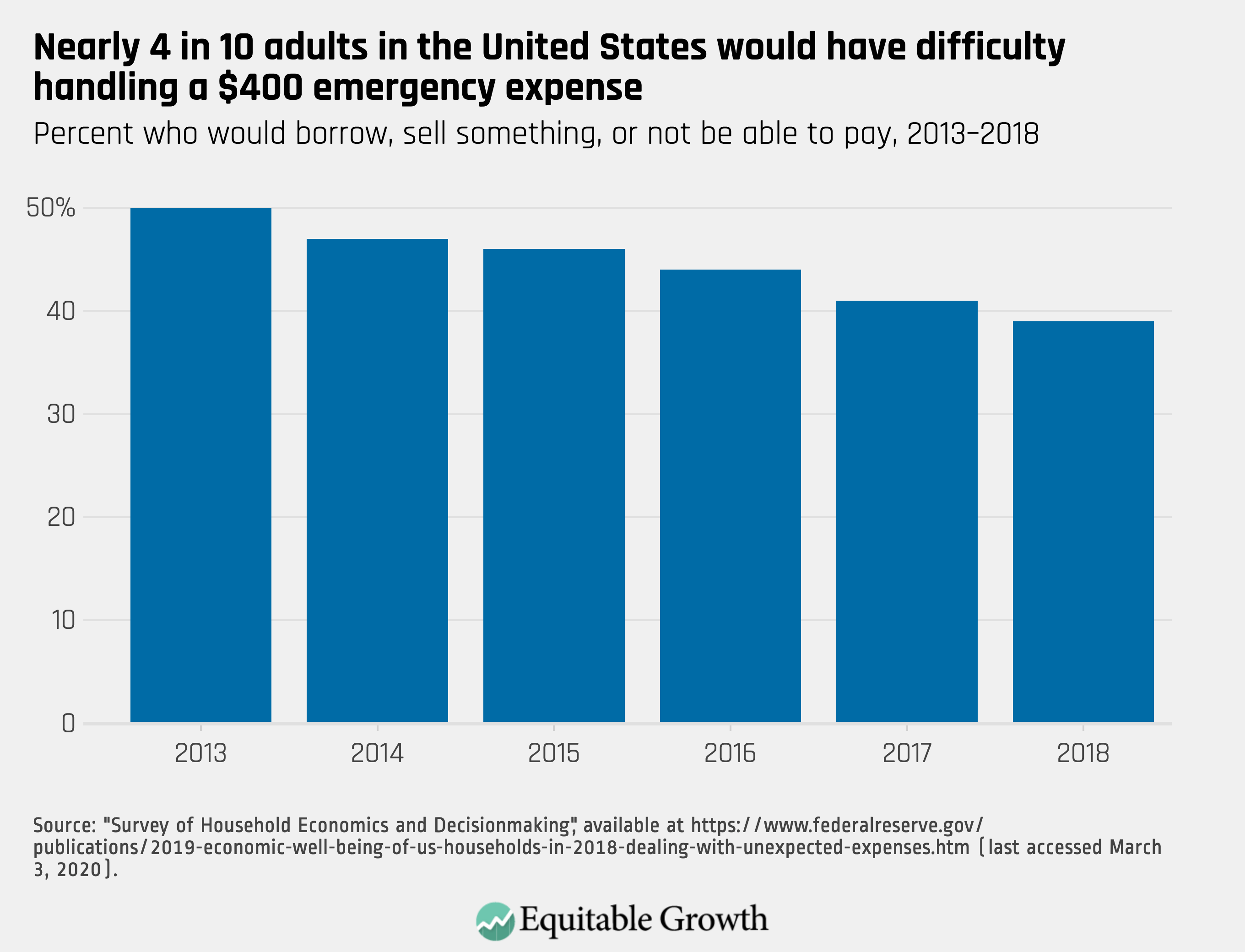

This pattern of economic recessions that fall more heavily on those with below-median earnings than the expansions that follow is a significant contributor to the four-decade rise in inequality that began around 1980. The inability of policymakers to identify and respond to this pattern is why many Americans have entered this recession in a delicate financial position, with nearly 40 percent saying they would struggle to handle a $400 emergency expense. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Similarly, families in the bottom 50 percent of wealth holdings only narrowly recovered their pre-Great Recession levels of wealth when the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession struck. With many of these families now plunged suddenly into unemployment, consumption will plummet, and the financial fragility of these families will further harm the entire U.S. economy.

New statistics from the Bureau of Economic Analysis that provide policymakers with a picture of who is benefitting from growth and who is suffering during recessions will give them the evidence needed to target legislation and build an economic recovery that benefits all Americans.

In conversation with Trevon Logan

For an equitable recovery, federal relief to deal with the coronavirus recession must be transparent to the U.S. public

U.S. policymakers’ decisions are only as good as the data they have to inform them, and the public’s trust in institutions is only as good as the information available to them.