Policy prescriptions for the flawed and unequal retirement savings systems that perpetuate U.S. economic inequality

Overview

Outside of homeownership, retirement savings are the most important way middle-class workers and their families build wealth in the United States. But this second pillar of wealth creation is woefully inadequate for most workers to prepare for a financially secure retirement. What’s worse, the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession are forcing many workers to tap their savings just to stay financially afloat.

Thirty percent of Americans with a retirement savings account withdrew a portion of their savings over the previous 2 months, with more than half using the money to cover necessary expenses such as groceries or housing payments, according to a May 2020 survey by a unit of the online lender LendingTree LLC. An additional 19 percent of savers planned to make a withdrawal, according to the survey. And the Federal Reserve’s just-released 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances, or SCF, finds that even before the pandemic, 18 percent of households with more than $2,500 in a retirement account had less than that in easily accessible liquid savings. More than 1 in 3 Black households and 22 percent of Latinx families found themselves in this precarious situation in 2019.

Then, there are so many other low- and middle-income workers who simply don’t have enough money, after monthly expenses, to save at all. Their sole savings plan is Social Security, which offers uneven retirement security due to its eligibility based on work history and an ineffectual minimum benefit formula. In fact, there is evidence that working Americans are heavily reliant on debt—the financially debilitating opposite of savings—just to make ends meet.

Indeed, brand new data on retirement savings from the Federal Reserve that we examine in this issue brief shows just how shaky and inequitable this second pillar of the middle class really is. The new data show that:

- Since the end of the Great Recession of 2007–2009, the only demographic group better-off in terms of retirement plan coverage are the rich—those in the top 10 percent of the income spectrum.

- Nearly two-thirds of Hispanic families and nearly one-half of Black families do not own a retirement plan, compared to roughly one-fourth of White families and fewer than one-tenth of high-income families.

- White, working-age families have more than 3.5 times the retirement savings of their Black counterparts and nearly 5.5 times more than Hispanic families.

- The top 10 percent of working-age families by income have more in retirement savings than the bottom 90 percent combined.

Some policymakers recognize these deficiencies in our retirement savings system and have proposed reforms that would:

- Increase Social Security’s minimum benefit and make other improvements to the program, paid for by raising payroll taxes on the very rich or by reducing the tax incentives for retirement savings that disproportionately benefit the wealthy

- Create, at the federal level, a more muscular version of the kind of state automatic-enrollment IRA plans now providing a streamlined way for some low- and middle-income families to save

- Make it easier for families to save for both short- and long-term needs by allowing taxpayers the chance to save a portion of their tax refund and employers to automatically enroll their workers in emergency savings accounts

In this issue brief, we examine the state of the retirement savings system in the United States, explore the deep racial and income disparities embedded in that system, and then detail these possible policy solutions.

The state of retirement savings in the United States today

Like homeownership, public policies are used to help workers save for retirement. There are tax-preferred retirement accounts, such as employer-sponsored individual retirement accounts, or IRAs, and 401(k)s, which allow families to defer taxes on savings, and the investment earnings on those savings, until withdrawal in retirement. These two “defined-contribution” savings vehicles are the most popular retirement plans.

But there are other types of tax-preferred retirement accounts. They include 403(b)s for nonprofits, a number of plans geared at small businesses and sole proprietorships, including Savings Incentive Match Plans for Employees, or SIMPLE IRAs, Simplified Employee Pension plans, Payroll Deduction IRAs, and Keogh plans for self-employed workers and small businesses. There also are so called Roth versions of some of these accounts, in which contributions are made with post-tax money so that withdrawals in retirement are entirely tax free.

These retirement accounts are the one place where the low- and middle-class savers get a modicum of exposure to stock investments, with all the upside and all the risk that comes with it. But still, the vast majority of stock holdings are owned by White, rich Americans.

It is important to remember, though, that private retirement wealth is in addition to Social Security, a public program that is guaranteed to all Americans who spend at least 10 years in the formal workforce. The current average benefit amount for Social Security retirees is $1,514 a month, but the amount is much lower for those with limited work history and low wages during their working years.

But even before Americans can start supplementing their Social Security by saving in tax-preferred accounts, they need to have access to an account at work. Technically, individuals can open an IRA on their own, but behavioral research tells us this is very rare because it takes initiative and know-how on the part of busy, cash-strapped families.

Also exceedingly rare in today’s economy are companies that don’t just provide an account but also take on the investment responsibilities and guarantee a defined benefit upon retirement. In a risk-shift of epic proportions, these defined-benefit plans have been largely replaced over the past three decades by defined-contribution plans, which include the vast majority of savings vehicles listed above (though some Keogh plans can be set up as defined-benefit plans and sometimes IRAs are considered a separate category).

New data on retirement coverage and account balances

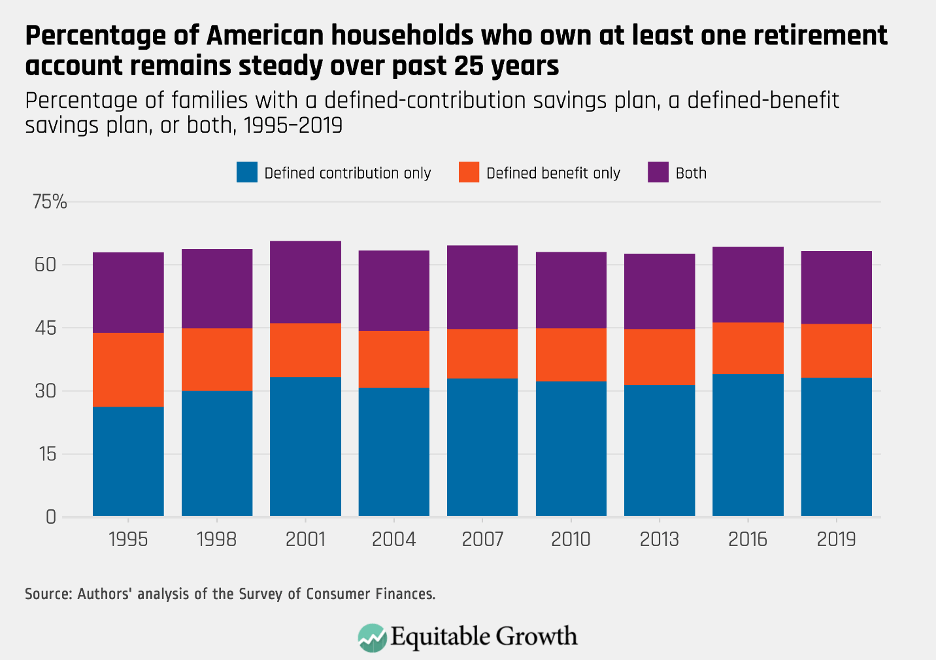

According to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, a triannual survey released just last week, 63.3 percent of families in the United States had a retirement plan of some kind in 2019, likely from a current or former job. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

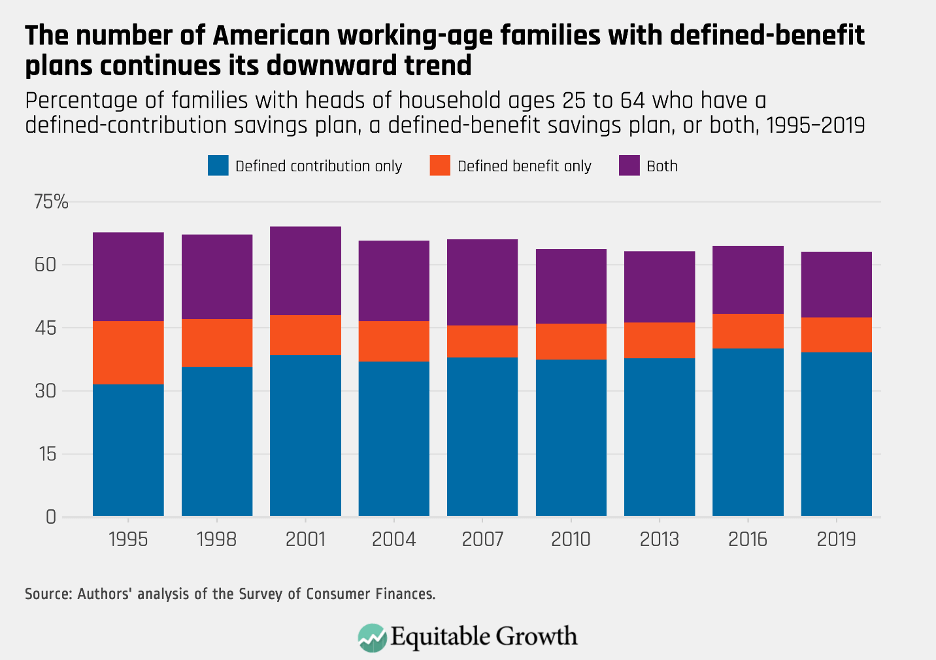

Among those families with a head of household ages 25 to 64, 63.2 percent owned a retirement account. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

These data are roughly aligned with the U.S. Department of Labor’s most recent National Compensation Survey, or NCS, which estimates that 71 percent of current workers are offered a retirement plan through their job, with 78 percent of those taking up the offer. This results in a 55 percent participation rate. Offer rates are considerably higher at unionized workplaces (94 percent), larger firms (89 percent at companies with 500 or more employees), and those firms with high-paid workforces (90 percent when the firm’s average wage falls in the top fourth of the income distribution).

The NCS numbers are from March 2020, right as the coronavirus pandemic was hitting the United States, and the SCF numbers are from 2019, before the current public health and economic crises. Both sets of surveys are telling policymakers more about the financial health of American families going into the coronavirus recession, rather than their current circumstances.

While overall retirement coverage has held steady over the past two-and-a-half decades, the topline numbers mask the aforementioned shift from defined-benefit to defined-contribution savings plans, which is particularly evident among working-age Americans, as seen in Figure 2.

The economic inequalities perpetuated by the U.S. retirement savings system

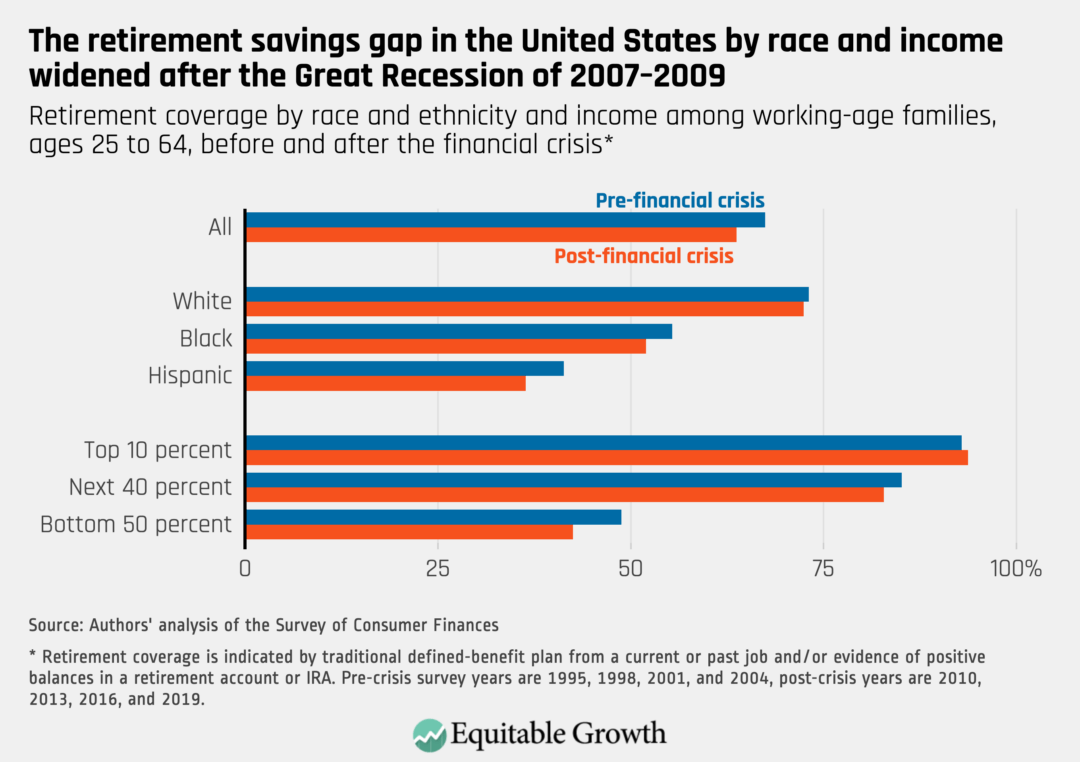

Also masked, to some extent, are the consequences of the 2008 financial crisis and resulting Great Recession, which is still delivering a lasting, negative impact on retirement coverage for working-age Americans. New data from the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances confirm this effect across race and income.

The data show that the only demographic group better-off since that crisis in terms of retirement plan coverage are the rich—those in the top 10 percent of the income spectrum. As a result, gaps in coverage rates between White, high-income families and everyone else have only widened. Nearly two-thirds of Hispanic families and nearly one-half of Black families do not own a retirement plan, compared to roughly one-fourth of White families and fewer than one-tenth of high-income families. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

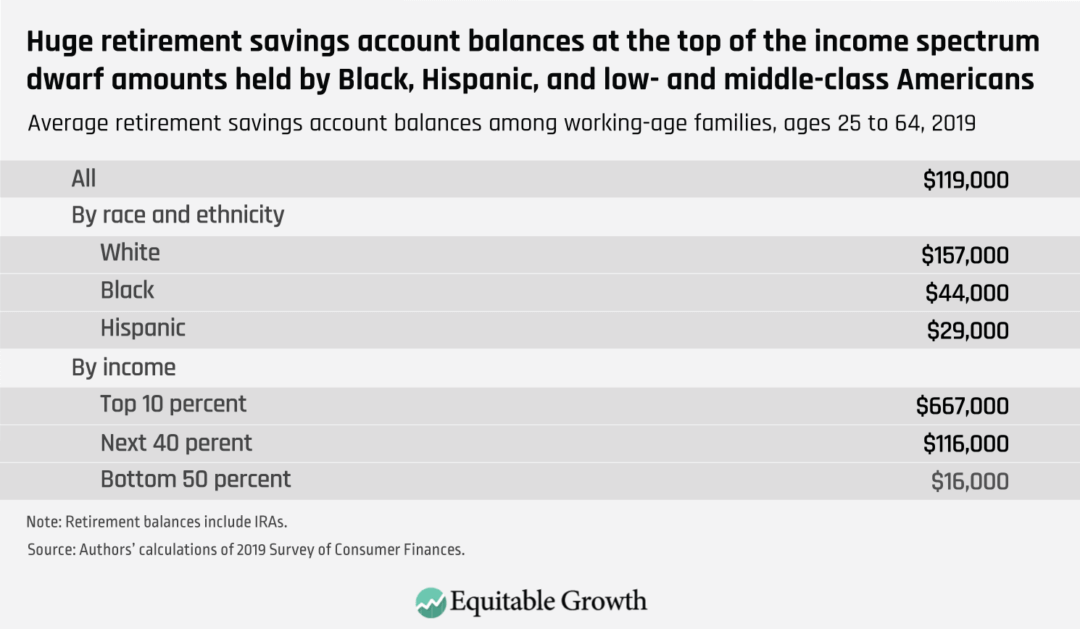

Retirement savings account balances also paint a distressing picture. The overall average of $119,000 would amount to just $505 per month in retirement. This calculation is based on the U.S. Department of Labor’s Lifetime Income Calculator and assumes the $119,000 is used to purchase a single annuity with no survivor benefit, effective at age 65. Even assuming that the $119,000 belonged to a 45-year-old today (so that it could grow at a 7 percent nominal rate per year over 20 years), the amount of lifetime income provided would be just $1,102 per month.

What’s more, that $119,000 average conceals substantial inequities. White, working-age families have more than 3.5 times the retirement savings of their Black counterparts and nearly 5.5 times more than Hispanic families. These racial discrepancies are illustrative of the way discrimination and structural racism permeate every aspect of economic life in the United States, going back more than four centuries. The top 10 percent of working-age families by income have more in retirement savings than the bottom 90 percent combined. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Additionally, early withdrawals from these retirement accounts often deplete account balances prematurely. According to a survey by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, at least 4 in 10 Latinx, Black, and Native American households have used up all or most of their household savings to cope with the consequences of the coronavirus recession. Some “leakage” from retirement accounts is a result of a recently enacted relaxation of early withdrawal penalties, which normally charge savers a 10 percent fee to access retirement money early. This relaxation happened because Congress wanted to help Americans suffering financially amid the coronavirus recession, but even when the penalty was intact, leakage is a common occurrence, especially for families that lack other sources of emergency savings.

This often makes sense from the household perspective: What good is $15,000 some 20 years from now if rent is due this week? According to the Fed’s 2019 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, 37 percent of families say they would have to borrow or sell something in order to cover a hypothetical $400 unexpected expense. And the just-released SCF finds that in 2019, 18 percent of households with more than $2,500 in a retirement account had less than that in easily accessible liquid savings. More than 1 in 3 Black households and 22 percent of Latinx families found themselves in this precarious situation.

Policy prescriptions

There are a number of interesting policy ideas for addressing this complex web of problems. The most sweeping proposals call for expanding Social Security. The Social Security 2100 Act proposed by Rep. John Larson (D-CT), for example, would increase the program’s benefits, including the minimum benefit. Boosting the minimum benefit would go a long way to reducing poverty in old age and reversing the aforementioned risk shift that has placed a heavy burden on individuals to manage their own investments and forecast their retirement spending needs decades into the future. The money for such an expansion could come from relaxing the cap on wages covered by the Social Security payroll tax, which today only applies to the first $137,700 in salary. The Social Security 2100 Act would apply the payroll tax to wages above $400,000, affecting the top 0.4 percent of wage earners.

Expanding Social Security also could be paid for by reducing the current tax incentive provided to private retirement savings. As is well-documented, the vast majority of the benefits of the current retirement tax breaks go to the wealthiest Americans—and actually provide more benefit, in both dollar and percentage terms, the higher up the income spectrum one goes. This upside-down system costs taxpayers roughly $250 billion each year, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation’s 2019 estimate of the following tax expenditures: Keogh plans ($14.4 billion), defined-benefit plans ($84.8 billion), defined-contribution plans ($125 billion), traditional IRAs ($18.2 billion), and Roth IRAs ($7.7 billion). In total, this amounts to roughly 15 percent of all federal income tax revenue.

Even if not coupled with an expansion of Social Security, curtailing this regressive tax expenditure would make for good public policy. Today, wealthy Americans (who surely would save a large proportion of their bountiful income even without any tax incentive) are able to shelter $57,000 a year in an employer-sponsored retirement account (assuming they are self-employed or have established a small business, which is easy enough to do), almost equal to the entire income of the median American family in 2019. It is true that business owners who make use of the $57,000 tax break must also make a plan available to their employees, but even today, with this generous incentive intact, many businesses choose not to sponsor plans at all.

Capping the total amount that could be saved in a tax-preferred retirement account (to, say, the amount needed to fund a very ample annuity) or limiting the tax deduction allowed for those at the upper reaches of the income spectrum would be sensible, if small, ways for the government to stop subsidizing the massive concentration of wealth at the top.

Not surprisingly, the financial industry opposes these potential reforms, claiming that reducing the tax incentives will mean less retirement savings coverage overall. What is perhaps more surprising, though, is the financial industry’s opposition to far more modest attempts to make the country’s savings system more egalitarian.

Take, for example, state automatic-enrollment IRA plans, or auto-IRAs. California, Oregon, Illinois, and a number of other states recently launched universal automatic enrollment plans that place into government-sponsored Roth IRAs a small portion (usually 5 percent) of the wages of all workers who don’t otherwise have access to a retirement plan at work. Workers are free to opt out, but most go along, a testament to the power of the default.

Because these state auto-IRA plans are large and publicly managed, the investment and administrative fees are low—an important consideration, given the confusing mix of high, often hidden fees that plague private-sector IRAs and 401(k)s. What’s more, because the contributions to these state-run IRA plans are post-tax, there is no penalty for taking the money out early should the saver need the cash sooner rather than later.

Even though these are small-dollar savers putting away their own money (there is no employer or government contribution), private retirement providers still feel threatened, which is one reason why conservative federal lawmakers, usually champions of states’ rights, continually push to preempt states’ ability to pursue these programs. Thankfully, the states have been able to proceed, though the programs are just getting off the ground. Even if implemented successfully, however, the account balances in these state auto-IRA plans will likely be small, given the low-income population they target and the lack of any employer or government match.

There are a number of federal proposals that would go further than the states in this regard. Most notable is the Saving for the Future Act from Sens. Chris Coons (D-DE) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN). The proposed law would expand access to portable plans to those currently without coverage and would require employer contributions.

Finally, to address Americans’ lack of short-term, emergency savings, a bipartisan group of senators have proposed the Refund to Rainy Day Savings Act and the Strengthening Financial Security Through Short-Term Savings Accounts Act. The former would allow workers to seamlessly put aside part of their tax refund into an interest-bearing account for use later in the year, and the latter would allow employers to automatically enroll their workers in a “sidecar” account for short-term savings, alongside the less liquid retirement account. These ideas mirror those that were included in our Vision 2020 essay by economists Emily Wiemers at Syracuse University and Michael Carr at the University of Massachusetts Boston on improving workers’ short- and long-term economic well-being.

None of these proposed policy solutions to the growing retirement savings divide would individually do enough to close the gaping divide between the haves and have-nots, and between White savers and savers of color. But these policy proposals are evidence-based ideas that, in the right political moment, could come together alongside other policy reforms to improve the financial security of low- and middle-class American families and unleash the country’s true economic potential.