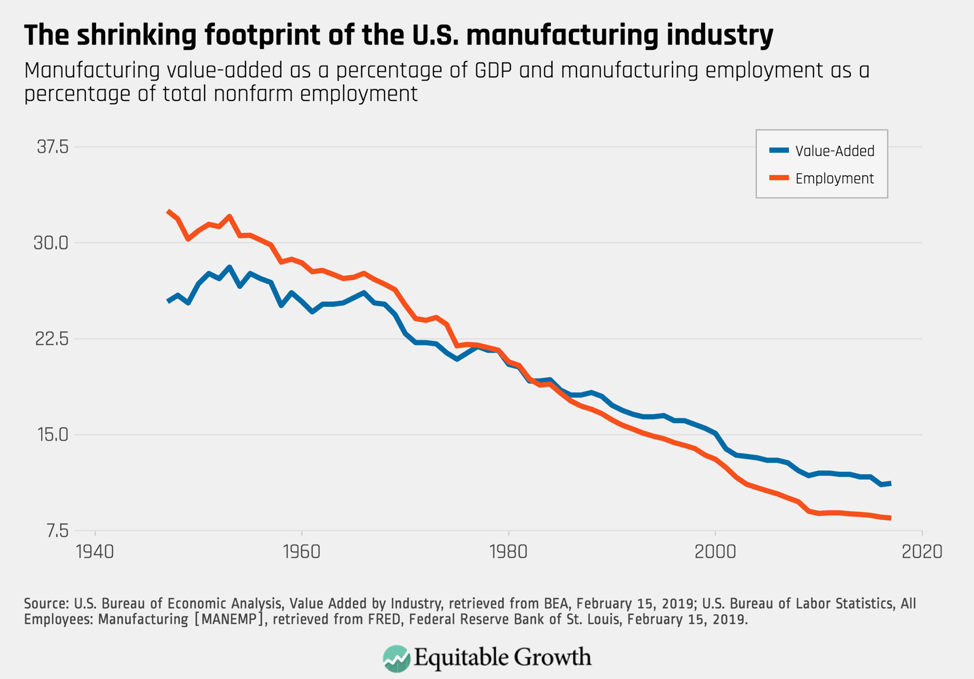

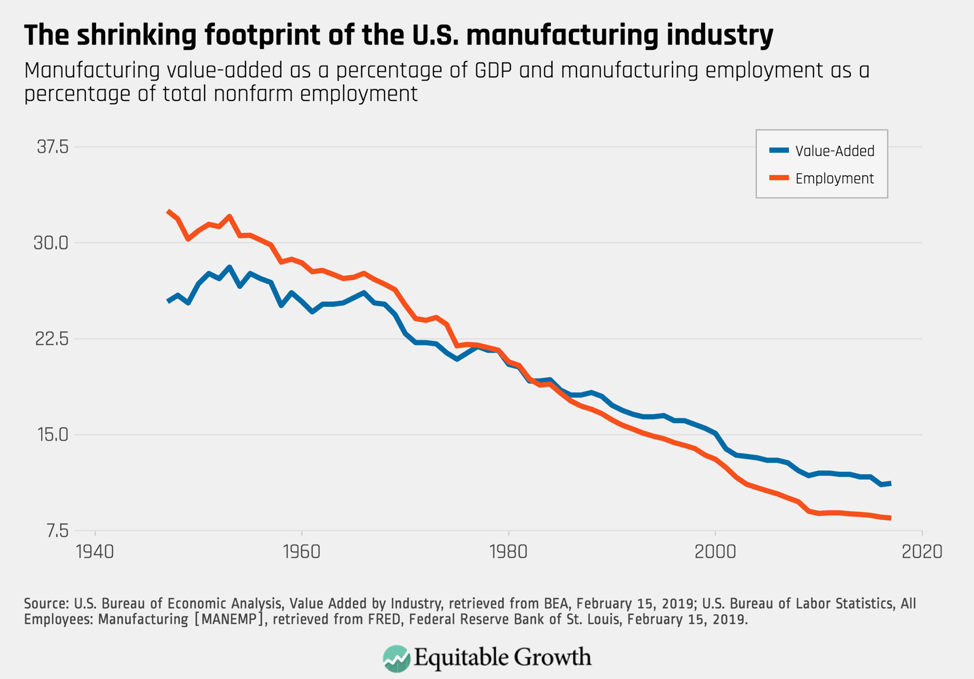

The United States manufacturing industry—once the central pillar of the American economy and a robust ladder to middle-class employment—today exhibits significant structural weaknesses that have metastasized over the past several decades. Since the early 1980s, the combined effects of automation and especially trade liberalization resulted in a dramatic decline in manufacturing employment, as well as in the sector’s value added, or the industry’s contribution to U.S. Gross Domestic Product. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Yet the United States’ robust-but-neglected research and development infrastructure and skilled workforce can open up opportunities for re-energizing U.S. manufacturing and creating high-tech job opportunities that pay well, produce globally competitive products, and create new strongholds of manufacturing innovation in regions across the country. Policymakers can and must offer support on multiple levels to guide this transition.

To understand the necessary steps to be taken, however, it is first important to analyze why and how U.S. manufacturing has weakened. Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member David Autor and other scholars identify the removal of trade barriers with China as a result of its admission to the World Trade Organization in 2001 as a particularly important cause of U.S. manufacturing’s recent decline in employment. Autor and his co-authors also find that these trade shocks produced a similar drop in manufacturing wages—with low-wage workers experiencing the largest losses. On the other hand, UC Berkeley economist and Equitable Growth columnist Brad Delong downplays the importance of trade deals and instead identifies our failure to invest in our middle class, human capital base, and engineering infrastructure as important culprits of manufacturing’s relative downturn in the United States.

Indeed, in addition to the decline in the quantity of manufacturing jobs, there has also been a pronounced drop in the quality of jobs for many manufacturing workers in the United States. While many of these workers were displaced into low-wage jobs in the service sector, those who remained in manufacturing are now paid lower wages and have fewer benefits. Researchers at the National Employment Law Project find that for the first time in decades, manufacturing workers now fall in the bottom half of the wage distribution, making 7.7 percent less than the median worker in 2013.

One of the reasons for this decline are anti-union policy changes at the state level and the shift of manufacturing employment to “right-to-work” states in the South. These developments hollowed out unionization in manufacturing industries from 1 in 3 workers 30 years ago to 1 in 10 today. In addition, sociologist Annette Bernhardt and other researchers at the University of California, Berkeley document a simultaneous explosion in contingent, temporary work within the manufacturing industry. Both of these trends led to reduced wages in this sector, with nonunionized and temporary workers making about $1.40 and $4 less per hour, respectively, than unionized and permanent employees in the industry.

Despite continuing challenges for manufacturing workers, the industry has partially recovered from the Great Recession a decade ago. After a sharp decline in employment and output between 2007 and 2010, the sector bounced back and experienced particularly strong growth beginning in mid-2016 with the rebound in national and global demand, although many of the jobs that have since been created pay lower wages and are less likely to be unionized. There are some indices that point toward emerging headwinds for the industry in the form of tariffs, higher prices, the fading impact of the 2017 tax cuts for corporations, and slowing global growth. Yet aggregate U.S. factory production rose in December 2018 by 1.1 percent, its largest growth rate in 10 months.

Nevertheless, manufacturing remains vulnerable to demand shocks and suffers from low aggregate levels of innovation. Economists Kevin Kliesen and John Tatom of the Federal Reserve argue that the U.S. manufacturing sector remains strong compared to its competitors in other developed countries. Importantly, however, Kliesen and Tatom point out that manufacturing’s health today remains largely contingent on the business cycle and that a dearth of innovation has depressed its output potential—despite highly innovative pockets in certain regions and subsectors of the industry.

To enhance the long-term health and resilience of the U.S. manufacturing sector, growing evidence indicates that policymakers and other stakeholders should encourage a shift to advanced manufacturing, or the deployment of innovative technologies such as artificial intelligence in manufacturing production. Traditional mass manufacturing of basic consumer goods increasingly relies on lowering labor costs, which are much higher in the United States than in many emerging economies, and cheaply maintaining bulky capital infrastructure, much of which has likewise deteriorated in recent decades in the United States.

Alternatively, advanced manufacturing relies on resources where the United States can (or at least should) have a competitive advantage because of a skilled workforce and a highly developed research and development infrastructure. Indeed, a McKinsey analysis finds that the U.S. could boost manufacturing GDP by up to $530 billion and employment by 2.4 million jobs over current trends—with the largest upside potential concentrated in advanced manufacturing industries such as aerospace, computers, renewable energy, and electronics.

From the perspective of labor, advanced manufacturing creates opportunities for high-skill, middle-class employment for millions of workers. As MIT’s Autor has studied, automation technologies can be a substitute for workers, thus explaining much of the employment decline in traditional manufacturing. But he also points out that automation technologies can be complementary to labor, creating demand for workers in roles in technology-intensive sectors where human supervision, creativity, and critical thinking are indispensable. As a result, workers interested in entering advanced manufacturing in the coming decades will enjoy a tighter labor market in which there is much greater demand for skilled workers than there is supply—compared to traditional manufacturing and service jobs in other sectors. Specifically, a Deloitte analysis finds that without further investments in upskilling, there will be 2.4 million unfilled job openings in manufacturing by 2028.

There is some evidence that this labor shortage might create incentives for employers in advanced manufacturing to offer good wages, benefits, and training opportunities such as apprenticeships to attract the talent they need to succeed. According to researchers at The Brookings Institution, the average wage in advanced industries is $90,000—almost twice the U.S. mean. Furthermore, a report by the nonprofit research organization Jobs for the Future finds that career prospects of workers in advanced manufacturing are “dramatically better” than those in traditional manufacturing. The reason: Jobs in production of basic consumer goods are often “static,” while advanced manufacturing jobs, especially those that convey both technical and management skills, can serve as “lifetime” jobs (or careers), as well as “springboard” jobs to other industries where workers can make use of the technical and management skills acquired in advanced manufacturing.

Despite these promising structural features, legal scholar Brishen Rogers at Temple University says more needs to be done to enhance U.S. employment laws. He argues that updating and expanding employment law will be necessary to ensure that middle-class wages, enhanced working conditions, and ample opportunities for employment are available in the high-tech workplaces of the future.

By building off U.S. strengths in human capital and R&D to enhance the production process, expanding advanced manufacturing would also be beneficial to U.S. firms because it would increase their competitiveness vis-à-vis manufacturers in other countries. A growing body of economic evidence demonstrates that advanced manufacturing technologies such as additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing) can help U.S. firms transition to production of more innovative, customized products with greater added value.

Similarly, so-called cloud manufacturing—or coordinating and upgrading manufacturing processes via networks online—can help reduce costs for firms by sharing expensive resources in these interconnected digital networks. Beyond bringing down firms’ costs, this more nimble and innovative production model allows U.S. firms to more easily respond to demand shocks and customize products to meet consumer trends. As a result, HEC Paris economist John Hombert and Princeton University economist Adrien Matray find that manufacturing firms that invest in R&D, and thereby increase product differentiation, are about twice as resilient to trade shocks.

A shift to advanced manufacturing would also increase competition within the U.S. manufacturing sector by reducing inequalities between firms of different sizes and in different regions. The innovations in production processes mentioned above stand to lower barriers to entry for new production, creating opportunities for small- and medium-sized enterprises across regions regardless of pre-existing manufacturing infrastructure. Substantiating this effect, much of the post-Great Recession manufacturing growth has been concentrated not only in large high-tech hubs such as the San Francisco Bay Area, but also in smaller cities characterized by highly skilled workforces, among them Orlando, Florida, Salt Lake City, Utah, and Raleigh, North Carolina.

In fact, many cities in the traditionally industrial Rust Belt, including the Michigan cities of Grand Rapids and Troy, have bounced back by creating an attractive regional ecosystem for manufacturing of biopharmaceuticals, electric and automated cars, renewable energy, and other innovative sectors. Notably, much of this production is small in scale. In Grand Rapids, for example, 80 percent of its 2,500 manufacturing firms have fewer than 250 employees. To further manufacturing growth along these lines, policymakers need to encourage less outsourcing of U.S. supply chains so that process innovation in manufacturing occurs in these and other manufacturing regions of the nation, as highlighted by Case Western University economist Susan Helper and her co-author at Case Western, Timothy Krueger, in a 2016 paper, “Supply chains and equitable growth.”

Increasing competition within the manufacturing sector would also reverse the current trend toward monopsony in the labor market and thereby improve manufacturing workers’ bargaining position for better wages, benefits, and working conditions. Equitable Growth economist Kate Bahn points to the increasingly negative ramifications of monopsony power—the disproportionate power of employers to set wages and other work conditions—in the contemporary labor market. In some ways, though, the U.S. manufacturing sector is an outlier in this regard. Temple University economist Doug Webber points out that relatively high levels of unionization in the sector may have held back the growth of monopsony in manufacturing compared to many service sectors such as health care and administrative support.

Still, manufacturing hasn’t been spared from the economywide trend toward monopsony. Indeed, economists Efraim Benmelech at the Kellogg School of Management, Nittai Bergman at Tel Aviv University, and Hyunseob Kim at Cornell University find that labor market concentration in U.S. manufacturing experienced relatively small, but notable, growth from 1977 to 2009. Turning to the effects of this change on workers’ earnings, MIT’s Autor, Harvard University economist and Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member Lawrence Katz, and MIT doctoral candidate and Equitable Growth Research Scholar Christina Patterson estimate along with their co-authors that this increase explains one-third of the decline in the labor share of income in U.S. manufacturing between 1997 and 2012. Additionally, Benmelech and his co-authors find that the negative effects of labor market concentration on wages in manufacturing are largest when unionization rates are low.

Working with labor, community, educational, and environmental stakeholders, policymakers can play an active role to make sure the necessary physical, social, and legal infrastructures exist to ensure the success of advanced manufacturing for both workers and firms. To start, policymakers must support the deployment of innovation in the process of production, which is at the core of advanced manufacturing. This is why federal, state, and local governments should invest heavily in public universities and other research institutions and increase these institutions’ connections with the private sector.

Additionally, policymakers should encourage and facilitate the adoption of new efficiency-enhancing technologies in the production process, especially for small businesses, and pursue robust antitrust enforcement to ensure competition in manufacturing industries. Case Western’s Helper, for example, argues for policymakers to encourage more collaborative supply-chain practices where innovation is shared among firms in addition to promoting “high-road” advanced manufacturing jobs through a variety of policy levels.

Finally, policymakers must keep middle-class opportunities for workers at the center of manufacturing’s future by developing lifelong training programs and apprenticeships that upskill workers and match them to jobs in the field, enforcing rigorous standards for wages, salaries, and employment conditions, and strengthening unions and other forms of collective action. As manufacturing advances and increases in productivity, policies and institutions need to be in place so that workers are able to share in the gains from this growth that their labor makes possible.

Many obituaries have been written for the U.S. manufacturing sector. But this habit of declaring manufacturing a thing of the past is undoubtedly premature. A nascent body of work indicates that a talent- and tech-driven manufacturing renaissance could well be on the horizon in the United States, but it is up to our policymakers to help lead the way to this innovative future.