February Jobs Day report: U.S. employment growth is still strong, but some care sector workers are being left behind

The U.S. economy continued its streak of strong month-to-month employment gains, adding 678,000 jobs between mid-January and mid-February. According to data released this morning by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the national unemployment rate continued to inch down toward its pre-coronavirus recession level of 3.5 percent, reaching 3.8 percent last month. The U.S. labor force participation rate, which has been one of the slowest-to-recover indicators throughout the crisis, made important gains over the past two months, jumping from 61.9 percent in December to 62.3 percent in February.

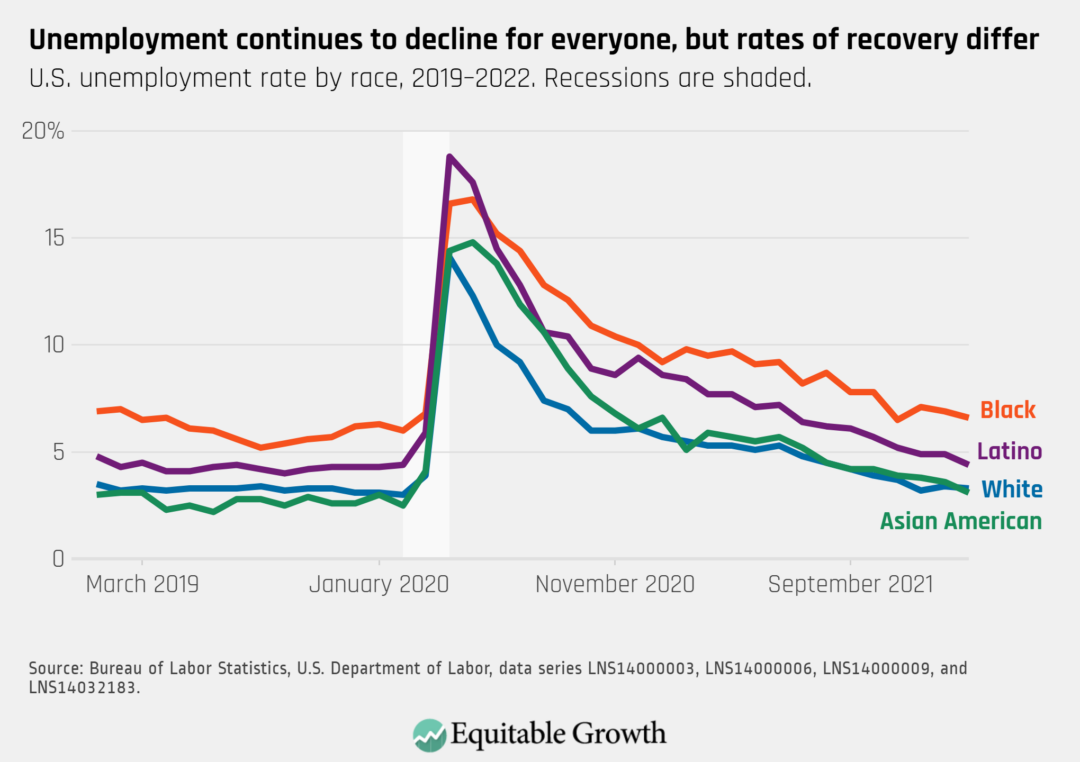

Across demographic groups, Black workers are currently experiencing a 6.6 percent unemployment rate, followed by Latino workers (4.4 percent), White workers (3.3 percent), and Asian American workers (3.1 percent). Overall, the workers of all these racial and ethnic groups experienced a decline in their unemployment rate last month. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

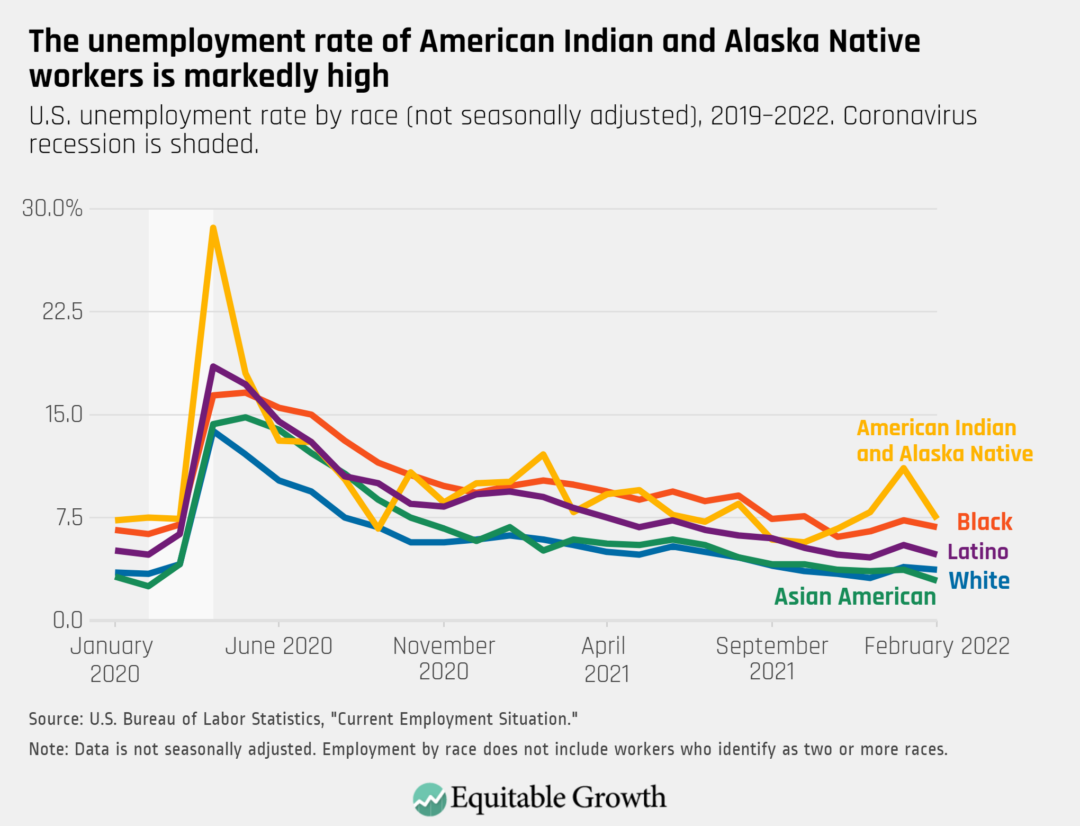

In addition, starting in February 2022 the BLS began publishing monthly unemployment data for American Indian and Alaska Native workers, showing that this group of workers is experiencing a higher jobless rate than any other major racial or ethnic group. While an important first step, experts Robert Maxim, Randall Akee, and Gabriel R. Sanchez at The Brookings Institution explain that shortcomings with the data highlight the need for policymakers and data collection agencies to continue working so that a more complete representation of how American Indian and Alaska Native workers are experiencing the labor market is visible and available in the monthly employment report. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Women’s employment and labor force participation have yet to recover

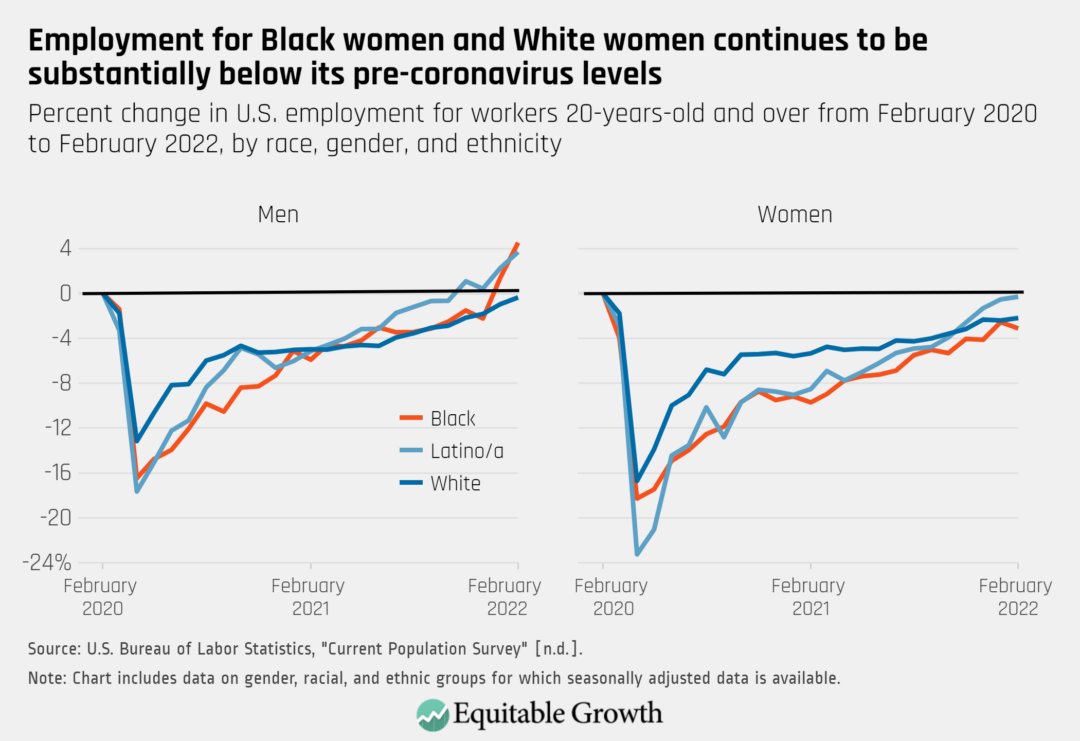

The most recent BLS data released today highlights that women workers continue to face disproportionately harsh labor market outcomes. In the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, women’s employment dropped dramatically, due to care responsibilities, occupational segregation, and other factors. And these same challenges continue to hinder the jobs recovery. The agency’s Employment Situation Summary shows that Black, Latina, and White women workers have all seen a substantially slower bounce back in employment than their male counterparts. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Compounding the slower recovery in employment is that many women left the labor force altogether to take care of their family and communities. As of February 2022, women’s labor force participation rate was 1.3 percentage points below its pre-coronavirus recession level. Women are unlikely to fully reenter the economy without a robust care infrastructure.

Taken together, the ongoing pandemic and economic hardships remain especially hard on women—and particularly on Black women. This causes important ripple effects in several areas of the economy, including severe disruptions to sectors that provide care services. These sectors are closely tied to women’s economic security and labor market outcomes because they both employ high shares of women and provide the caregiving infrastructure that research shows is critical to supporting women’s labor force participation throughout the economy.

Critical care economy sectors continue to lose jobs, harming women’s employment options

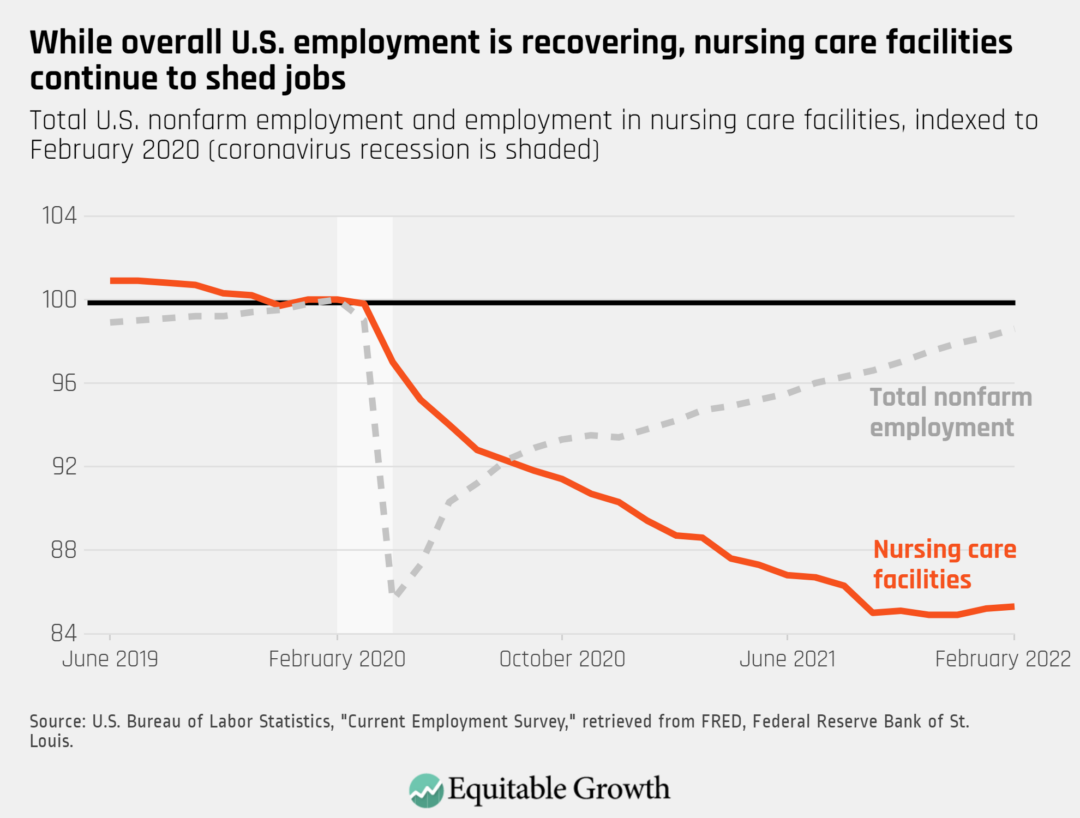

Let’s take a closer look at the importance of the care economy to women’s labor force participation. Even though overall U.S. employment is recovering at a remarkably strong pace, sectors such as nursing care facilities not only have not recovered from the initial blow of the coronavirus pandemic, but also continue to shed jobs almost two years into the recovery. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

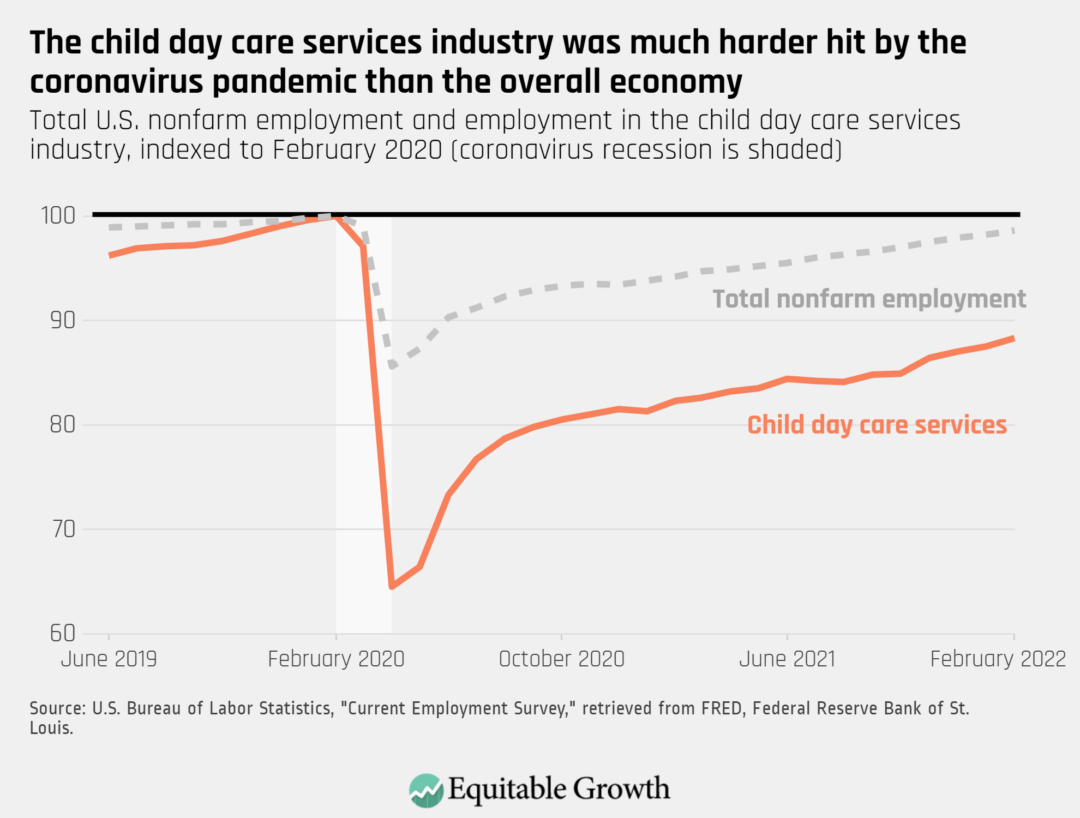

Other care sectors are recovering jobs, but experienced such massive employment losses at the onset of the coronavirus recession that they are still well below their pre-pandemic employment levels. The child day care services sector, for instance, saw a 35 percent decline in employment between February and April 2020 alone, and is still at a 12 percent jobs deficit (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Why are these care sectors struggling to join in the jobs recovery? At least part of the answer is that the coronavirus crisis made already-precarious jobs even more difficult and insecure. Nursing homes, for example, came under the spotlight early in the pandemic as many facilities became hotspots of coronavirus infections. Health risks in conjunction with stressful working conditions, extremely low pay, and lack of access to benefits for staff—a workforce predominantly made up of women workers—deepened an understaffing crisis that was already hurting the sector well before the onset of the pandemic.

Indeed, care work is consistently undervalued. Views around paid and unpaid care work in the United States are informed by stereotypes around gender, race, and ethnicity. The poor job quality for care workers today is also part of a racist legacy of excluding domestic workers from labor protections under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Home care workers have only recently been included in the Fair Labor Standards Act’s federal minimum wage and overtime protections, and many domestic workers are still denied basic labor rights and protections.

Today, women account for 88.6 percent of home health care workers and 94 percent of child care workers, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, with women of color and immigrant women making up disproportionate shares of both workforces. Wages and job quality remain low, and benefits are scarce. EPI reports that home health care workers and child care workers are far less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance or retirement coverage than the workforce as a whole.

As the labor market continues to bounce back (the country is currently 2.1 million jobs below its February 2020 employment level), it will be essential that care sectors of the economy add many more good-quality jobs. Research by Rachel Dwyer at The Ohio State University shows that while the number of care economy jobs grew at a faster pace than virtually any other job group in the three decades that followed the early 1980s, the undervaluing of these jobs was also a substantial contributor to the gendered and racialized job polarization of the overall U.S. economic structure.

Invest in the care economy and its workforce for a more equitable recovery

As Equitable Growth highlighted in October, poor job quality in care-providing sectors has hindered employment growth and presented a clear risk to the country’s long-term economic trajectory. The lack of public investment in care sectors in the United States is a policy choice that leaves workers and families more vulnerable to economic shocks and slows the country’s broader recovery. As economists Sandra Black at Columbia University and Jesse Rothstein at the University of California, Berkeley explain, the lack of public investment in areas such as child care and long-term care insurance—despite clear market failures—shifts large costs and risks to families and exacerbates economic fragilities.

These vulnerabilities cause ripple effects throughout the economy, contributing to a system that fails families, care workers, and society at large. For instance, as Equitable Growth Policy Analyst Sam Abbott writes, the child care market depends on parent fees, and therefore is “particularly exposed” to economic conditions in ways that make the child care market slower to recover than other parts of the economy. Yet, Abbott notes, public investment was a source of resiliency for care providers during the coronavirus pandemic and recession, as “child care programs that received public funding, rather than solely relying on parental fees, were better able to retain their enrollment and staff during the coronavirus recession.”

Care investments and improved job quality also have direct implications for public health during the pandemic, as Georgetown University’s Krista Ruffini described in a recent working paper. Ruffini finds that higher wages and better workplace conditions for nursing home staff can improve the safety and health of workers and residents, with a clear role for both raising the minimum wage and greater public investments to support staff wages.

Investing in the care economy and in job quality for low-wage workers can not only strengthen care access and support women’s labor force participation but also protect vulnerable workers during times of crisis and drive more equitable growth during periods of recovery. Research shows that raising labor standards, wages, and job quality for care providers and other workers, along with policies to support worker power and strengthen the country’s social infrastructure, is vital to improving economic security for workers and their families.