Brad DeLong: Worthy reads on equitable growth, January 11–17, 2019

Worthy reads from Equitable Growth:

- Submit! The deadline for Equitable Growth’s Request for Proposals is January 31!

- Read “In Conversation with Atif Mian” to understand how to do micro foundations right. In his conversation with Heather Boushey, Mian says: “Our number of theories is much larger than the number of observations we have, which is a limiting factor of macroeconomics just from an empirical standpoint … This is where I feel micro data comes in … Let me just give you one quick example … The 2000s … you see credit going up, you see aggregate income going up as well … If it were higher incomes that were driving credit growth, then since income growth is concentrated in the top 1 percent, we should really expect the top 1 percent to borrow a lot more … Yet that clearly was not the case. So, even a basic breakdown of the data along a more micro level starts to give you a lot more insights than you might be able to deduce from just looking at the macro aggregates.”

- Let me hoist this column by Kate Bahn from last year, in which she summarizes the evidence that imposing work requirements simply does not work because it has none of the benefits that people wish that it would have and all of the drawbacks you can think of. In “Work Requirements for U.S. Public Assistance Programs Don’t Work,” she explains: “Analysis from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities finds that imposing work requirements simply doesn’t work. One reason is because increased red tape may lead to eligible recipients losing their benefits even though they are eligible for them. People with volatile work hours or who hold multiple jobs may have a hard time collecting and submitting sufficient documentation to demonstrate they are working regularly. As CBPP points out, completing work-requirement red tape is even harder for self-employed workers, which should be cause for concern as gig-based employment becomes more prevalent.”

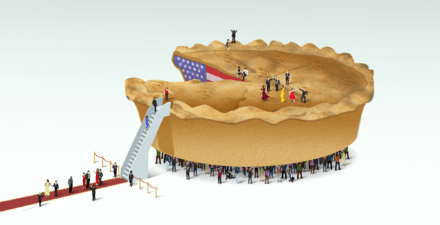

- Read Liz Hipple on where the labor market is failing—and on how we have learned about these failures from economic research and could learn useful things about other market failures if only we spent more money getting better data. In “U.S. Economic Policies That Are Pro-Work and Pro-Worker,” she observes: “The Measuring Real Income Growth Act, introduced by Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), would allow policymakers to see which income segments, demographic groups, and geographic areas of the country are actually experiencing economic growth by disaggregating the Gross Domestic Product statistics that the federal government produces. This is a key first step to better measuring … There are clearly ways that policy could be doing a better job … Unpredictable schedules, the lack of paid leave, and monopsony power are all examples of areas where research shows that breakdowns in the market.”

Worthy reads not from Equitable Growth:

- Is employer-side monopsony the reason effective labor demand appears to be so inelastic when increases in the minimum wage are concerned? Or are we just not being creative enough? And why does the idea that in America today, minimum-wage increases are “job killers” continue to have rhetorical purchase? Read Doruk Cengiz, Arindrajit Dube, Attila Lindner, and Ben Zipperer in their working paper “The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs: Evidence from the United States Using a Bunching Estimator,” in which they write: “Infer[ring] the employment effect of a minimum-wage increase by comparing the number of excess jobs paying at or slightly above the new minimum wage to the missing jobs paying below it … using 138 prominent state-level minimum wage changes between 1979 and 2016 … we find that the overall number of low-wage jobs remained essentially unchanged over 5 years following the increase. At the same time, the direct effect of the minimum wage on average earnings was amplified by modest wage spillovers at the bottom of the wage distribution.”

- Back in the depths of the Great Recession, employers said that they wanted, needed, and required college graduates and the highly experienced. But what they meant was that they thought high unemployment meant that they could get overqualified workers when they went to the labor market. Now that unemployment has fallen, these needs and requirements have vanished. Employers still want overqualified workers. But they are no longer asking for them because they no longer expect to be able to get them. Read Matthew Yglesias, “The “Skills Gap” Was a Lie,” in which he writes: “The skeptics were right … employers responded to high unemployment by making their job descriptions more stringent. When unemployment went down thanks to the demand-side recovery, suddenly employers got more relaxed again … The skills gap was the consequence of high unemployment rather than its cause. With workers plentiful, employers got choosier. Rather than investing in training workers, they demanded lots of experience and educational credentials. And while job skills are obviously important, when the labor market is healthy employers have incentives to try to impart skills to workers rather than posting advertorial content about how the government should fix this problem for them.”

- Adam Tooze attributes to me the idea that many of the problems of the past decade stem from the fact that we had “the wrong crisis” and that we then, in large part, reacted to the crisis we had expected but did not, in fact, have. But I think this point is more Matt’s than mine. Read Matthew Yglesias, “The Crisis We Should Have Had,” in which he writes: “The U.S. economy from 2002-2006 … someday soon, the capital flows would come to an end … the value of the dollar would crash, restraining inflation would require high interest rates, and the U.S. economy would feature a period of painful restructuring … Sections of Tyler Cowen’s The Great Stagnation” are about the crisis we should have had … Spence’s “The Next Convergence” … Stiglitz’s recent Vanity Fair article … Mandel’s piece on the myth of American productivity … I can name others … [and] an awful lot of the Obama agenda has been about efforts to address the crisis we should have had. That’s why long-term fiscal austerity is important and why there was no ‘holy crap the economy’s falling apart, let’s forget about comprehensive reform of the health, energy, and education sectors’ moment back in 2009.”

- Increasing attention to leverage cycles and collateral valuations as sources of macroeconomic risk seems to be very welcome. Leverage and trend-chasing are the two major sources of demand-for-assets curves that slope the wrong way: When prices drop demand falls, either because you need to liquidate in order to repay now-undercollateralized loans or because you do not want to be long in a bear market. And there is every reason to think the government need to take very strong steps to make effective demand curves slope the proper way. Read Felix Martin, “Will there be another crash in 2019?” in which he writes: “One important detail is that this effect is achieved not only directly, by adjusting the cost of borrowing, but also indirectly by making assets cheaper or more expensive. When the interest rate available from the central bank falls, other, higher-yielding assets become more attractive—so their prices get pushed up. When the policy rate rises, by contrast, alternative assets look relatively less alluring—so they are sold down, until their price falls enough to entice savers back. Because borrowing at any scale depends not just on cost but on collateral, this valuation effect of monetary policy constitutes a second important channel of its effectiveness. When interest rates fall, the value of capital assets used as collateral for loans—be they shares, intellectual property, or real estate—inflates. As a result, credit becomes not only cheaper to service, but easier to access.”

- The disjunction between beliefs in the market community and among policymakers makes me most worried about the business cycle outlook. Market observers understand how and what the Federal Reserve believes but are right now betting that events will give it a shock and force it to reverse policy. Such confidence that reality will give a shock that policymakers will not be able to ignore is worrisome. Read Muhammed El-Erian, “Why Fed and Markets Don’t Agree on Prospects for Interest Rates,” in which he writes: “The markets, anticipating no hikes this year and cuts thereafter, estimate the Fed Funds rate in 2020 a full percentage point below the median of the central bank’s dots … There simply isn’t enough data as yet to point with a high degree of confidence to a dominating explanation or combination of explanations … historically based analytical models may not be sufficiently structurally robust to capture this moment.”