When will everyone who wants to work have a job in the United States?

Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) prefaced her questions directed to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell at last week’s semiannual Humphrey-Hawkins congressional hearings with a history of the full employment mandate. In her remarks, she noted that:

- In 1944, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a Second Bill of Rights, including a right to a “useful and financially rewarding job.”

- Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall argued that the “right to a job” was secured by the 14th Amendment.

- Martin Luther King Jr. called for a job to all “who want to work and are able to work.” She underscored that the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was a march for “economic justice.”

- After Dr. King’s assassination, Coretta Scott King carried on fight for the full employment mandate. She attended the signing of the Humphrey-Hawkins Act in 1978, and the reason why Powell was there to testify.

Rep. Pressley then asked Powell, “Yes or no, given persistent concerns about inflation, do you believe the Federal Reserve can achieve full employment?”

Powell began by thanking her for the history, which he said he “did not know.” To her question, he said, “[Full employment] that’s our goal. We will never accomplish our goal. We certainly have made some progress.” His reply is notable for its honesty and troubling for its pessimism. Congress gave the Federal Reserve its dual mandate of maximum employment and stable prices. Fed officials remain confident they will achieve their desired inflation target of 2 percent, so why give up on full employment?

Today, with the national unemployment rate at a half-century low of 3.6 percent, policymakers and the American public should reflect on the history of full employment and what it means to the well-being of families. The Federal Reserve has been repeatedly surprised over the course of the current economic expansion by how much more the U.S. labor market could strengthen. The national unemployment rate is now 0.5 percentage point below the Fed’s longer-run estimate that they made in December 2015. One-half of a percentage point may sound like a small difference, but it translates into 2 million more people with jobs today.

In addition, the official unemployment rate likely overstates how close we are to full employment. In a recent survey, 1 in 10 adults said they were not working and wanted to work. That rate is more than twice the official unemployment rate. The discrepancy is explained by adults who have not applied for a job in the past year. The official unemployment rate is only out of the people who are at work or searching for work. It does not include people who have been on the sidelines for so long that they have given up on finding a job. What’s more, another 2 in 10 adults were working but said they wanted to work more hours.

Taken together, these findings suggest that many people are not fully employed. During his testimony, the Fed Chair was correct when he pointed to recent progress in the labor market, which is definitely encouraging, yet the dismissals by Powell and his colleagues at the Federal Reserve at what more they could achieve on the employment front is not.

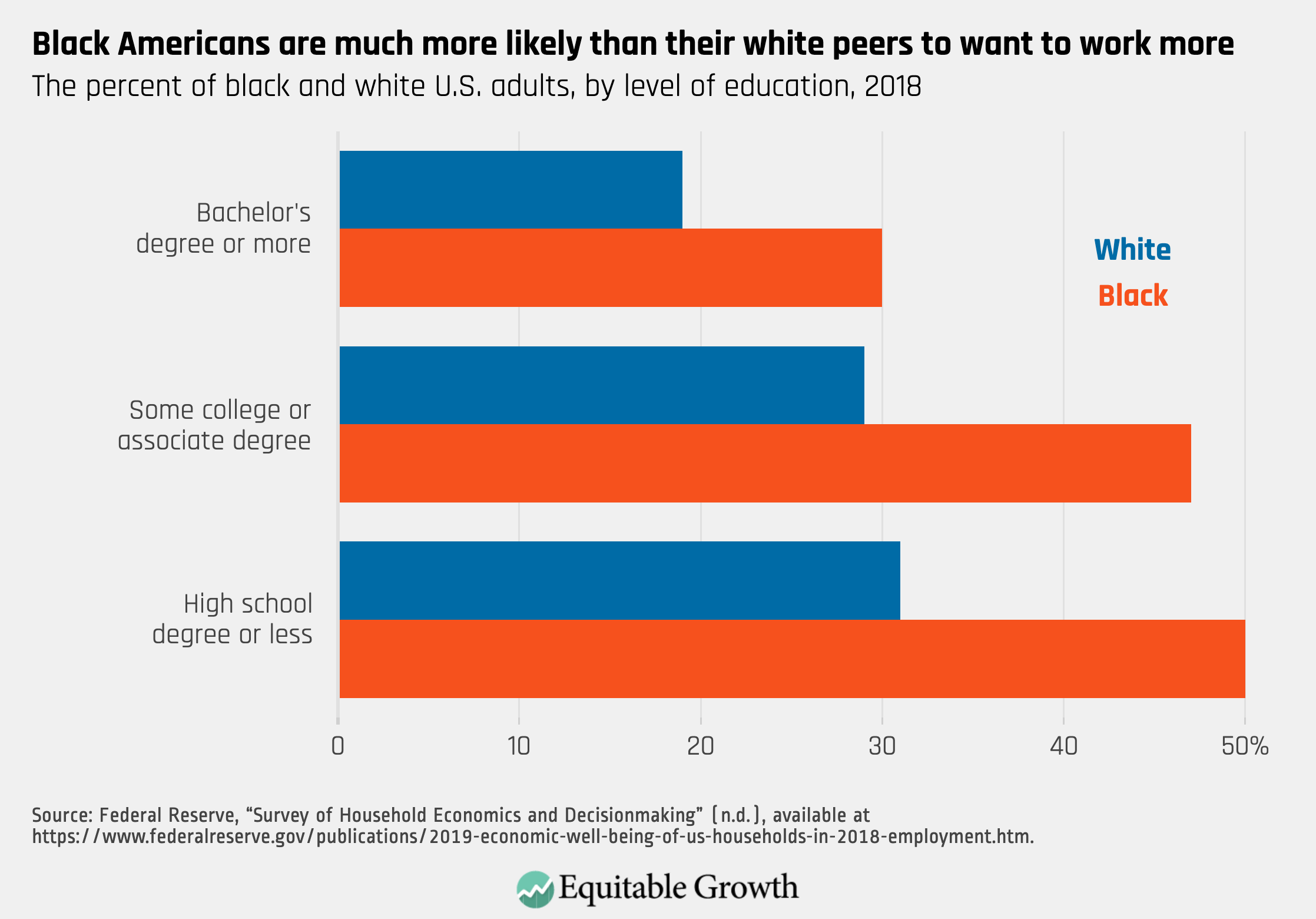

The fight for full employment rose out of the civil rights movement. Many decades later, black people remain considerably further from full employment than white people. At every level of education, African Americans are much more likely to say that they want to work more. This combines those who want a job and those who want more hours. Notably, black people with a bachelor’s degree or more are as likely as white people with a high school degree or less to want more work. It is impossible to say the U.S. economy has attained full employment or economic justice. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The Federal Reserve recognizes these racial disparities, as well as other dimensions of economic inequality. In 2019, Powell spoke at a town hall meeting with teachers. He told them, “We want prosperity to be widely shared. We need policies to make that happen.”

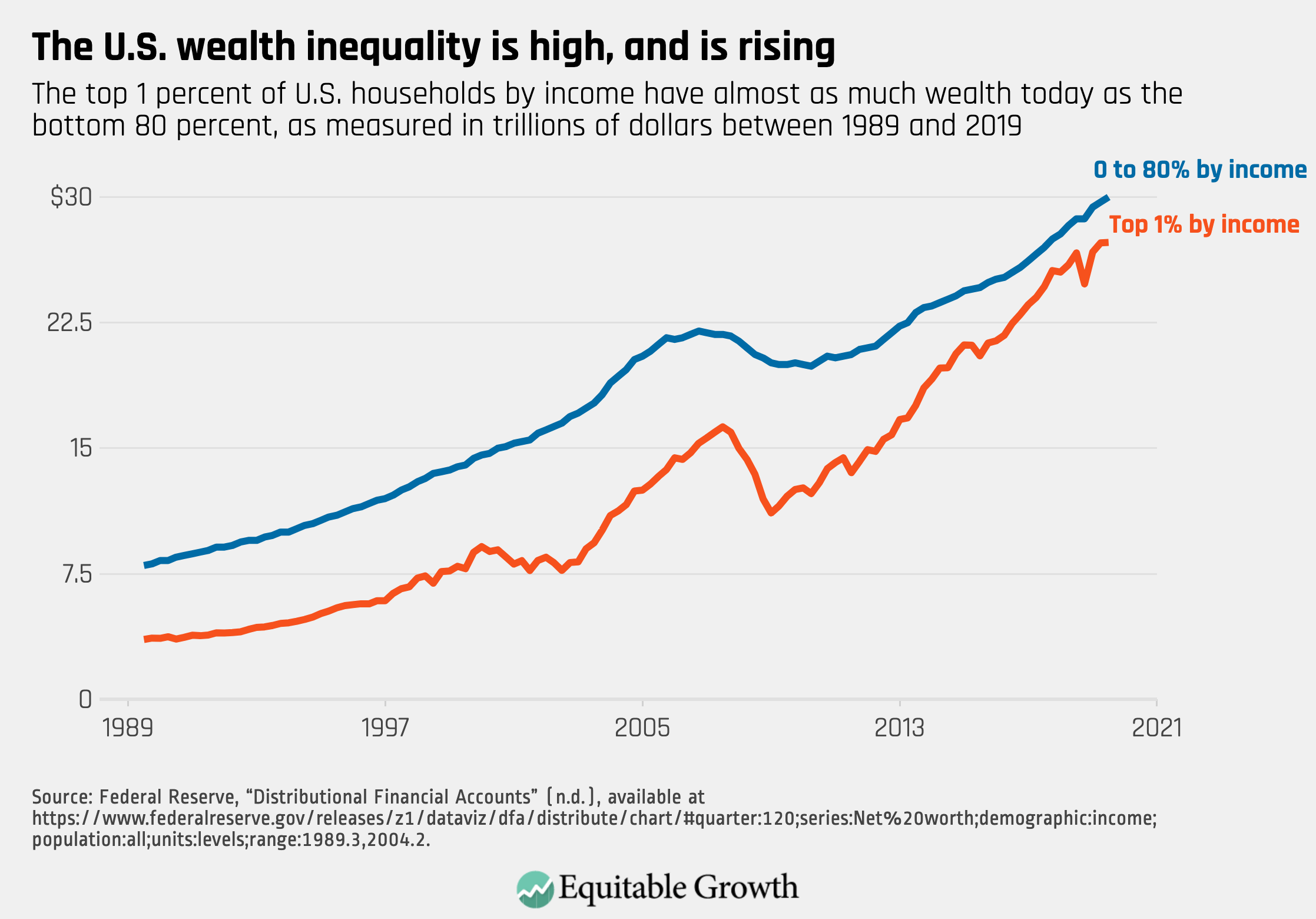

That’s why the Federal Reserve and other parts of the government have their work cut out for them. Wealth and income inequality is high, and is rising. Households with incomes in the top 1 percent own almost $30 trillion dollars in wealth. Their wealth is nearly as much as the wealth owned by the bottom 80 percent of households by income. Eighty times as many households, including the middle class, have wealth on par with the top 1 percent of income earners. These massive differences in wealth have risen since the Great Recession and show no signs of abating. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Clearly, the Federal Reserve alone cannot deliver shared prosperity. Fiscal policy is equally important. Even so, monetary policy can support the ongoing economic expansion and the gains in the labor income. Full employment will not deliver wealth equality without other government policies. But the Federal Reserve has a mandate from Congress to do its part and must remain dedicated to making sure anyone who wants to work and is able to do so has work.

Unfortunately, the track record of the Federal Reserve during the current expansion does not inspire confidence. At the Humphrey-Hawkins hearings 4 years ago, the national unemployment rate was 4.9 percent. That rate equaled the median of estimates at that time by the members of the Federal Open Market Committee of the unemployment rate’s longer-run normal level. That alignment implied that the unemployment rate was at or near the level below which the Federal Reserve believed inflation would begin to rise. They were wrong: inflation did not increase, even as the unemployment rate declined more.

Moreover, the FOMC members’ perception of a strong labor market then justified their decision to increase the federal funds rate in December 2015. It was the first time the Fed had raised rates since the financial crisis in 2008. We know today that the unemployment rate could go much lower without inflation reaching the 2 percent target set by the Federal Reserve.

Rep. Pressley in last week’s congressional hearings pressed Powell on that decision to raise rates in 2015 and the Fed’s underestimation of the strength of the U.S. labor market. Powell made clear that he was among the officials who had voted to raise rates. He was open about the mistakes of the past, adding that “hindsight is 20/20.” As he said, policymakers must make decisions with the information that they have at the time.

Even so, the Federal Reserve has not delivered on either side of its dual mandate—inflation or employment—for more than a decade. Given the data available today on its policy decisions, it seems like Powell is right, and we never will reach full employment.