Wealth as a driver of income and consumption mobility in the United States

When most Americans think about how economic well-being transfers from parents to children, they will likely think about income, consumption, and wealth. After all, parents’ ability to provide for and invest in their children’s future is directly related to the parents’ income and wealth.

As it turns out, the well-being of children as they grow up and leave home is much more strongly related to income and to consumption than it is to wealth. Does this mean parents’ wealth is relatively unimportant in determining the well-being of their children when they grow up? No. Even moderately high parental-wealth for lower-income parents improves children’s well-being in adulthood. Their children, on average, have higher well-being when they grow up than children whose parents had higher income but with low wealth. The same holds true for their children’s consumption in adulthood.

These findings in our new working paper, “Intergenerational Mobility using Income, Consumption, and Wealth,” are important for policymakers to understand as they consider ways to encourage greater economic mobility in our society. The high wealth inequality in the United States due to decades of stagnant income growth among those toward the bottom of the income distribution presents a clear challenge to our society and future U.S. economic growth.

Our working paper uses 50 years of data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, or PSID, to study the correlation between parental well-being and the well-being of their children when they grow up. Our research builds on the important work of the Opportunity Insights team and former Equitable Growth Steering Committee member Raj Chetty and his co-authors. The Opportunity Insights team uses income across generations to measure intergenerational economic mobility.

One of the value-adds in our paper is that we use not only income, but also consumption and wealth. Consumption may better represent families’ standards of living than income in a year because families may borrow money when income is low, or conversely, may save money for emergencies or retirement. Consumption, in short, can indicate long-term standards of living better than income.

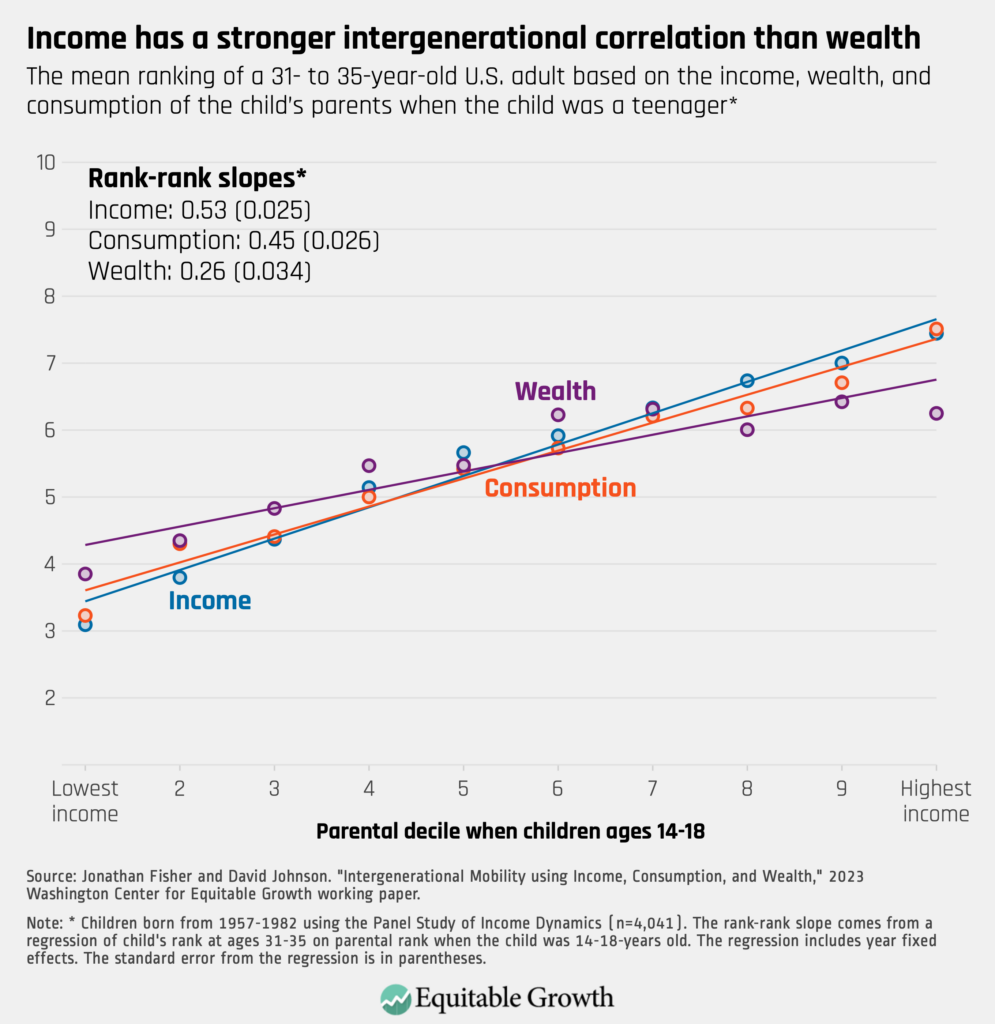

Wealth is the most unequally distributed component of inequality in the United States and may be the easiest to transfer across generations. Yet we find the strongest correlation between parents and children when they grow up is for income. Consumption has a slightly weaker correlation, and wealth has the weakest correlation.

For income, a typical child born into the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution will end up on average around the 30th percentile when they are in their 30s. A typical child born into the top 10 percent of the income distribution will end up on average around the 74th percentile when they are in their 30s. To help get a sense of the difference, the typical 31-to-35-year-old today at the 30th percentile has income around $56,000. The 74th percentile is more than double at $132,000.1

For consumption, a typical child born into the bottom 10 percent of the consumption distribution will end up on average around the 32nd percentile when they are in their 30s. A typical child born into the top 10 percent of the consumption distribution will end up on average around the 75th percentile when they are in their 30s.

For wealth, the percentile gap difference in adult wealth is much smaller. A child born in the bottom 10 percent of the wealth distribution on average ends up around the 40th percentile when reaching the ages of between 31 to 35, and a child born into the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution ends up around the 65th percentile at the same ages. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Does this lower correlation for wealth mean that we should be less concerned about the high levels of wealth inequality in the United States? The answer is no for two reasons.

First, the PSID data misses the very top of the wealth distribution. These families with generational wealth may be able to guarantee that their children and their grandchildren remain wealthy. Ongoing research by Equitable Growth grantee Fabian Pfeffer at the University of Michigan will enable researchers and policymakers alike to look at the intergenerational correlation in wealth among the ultrawealthy.

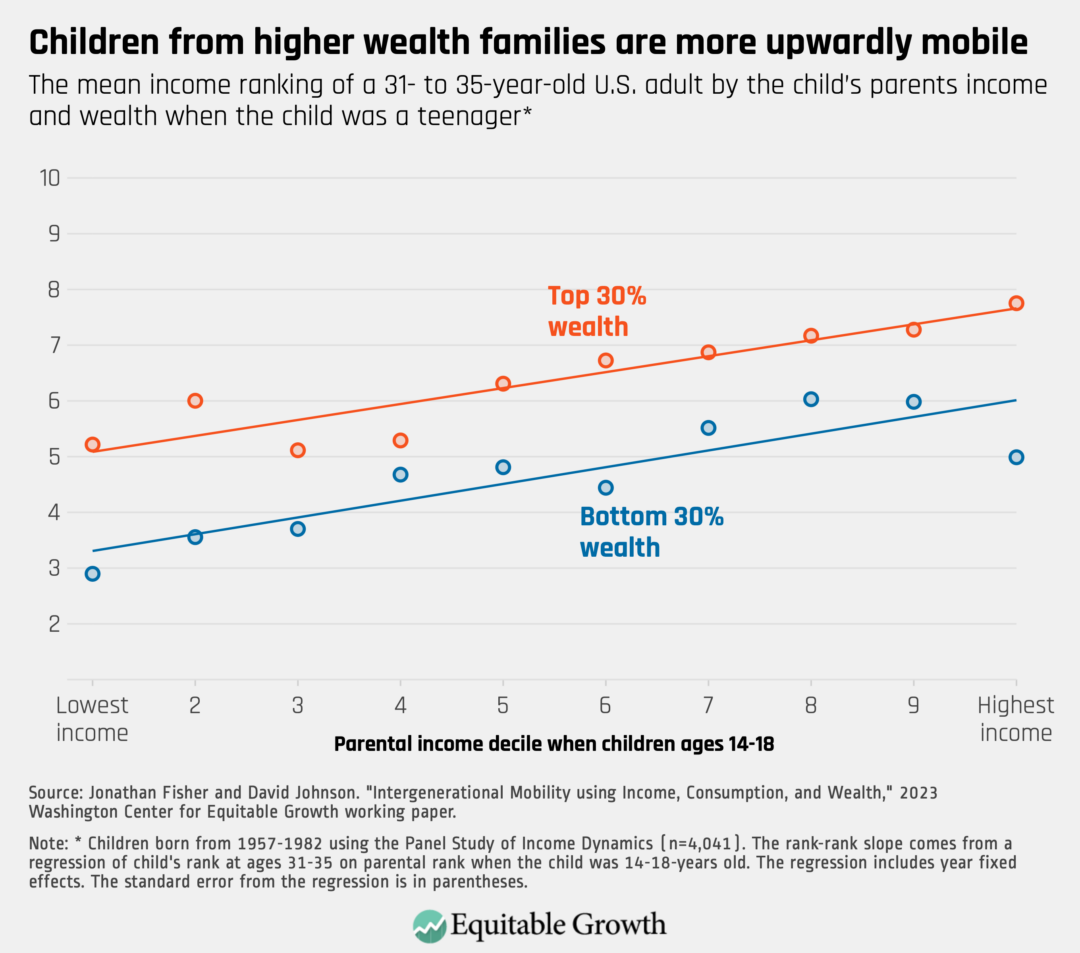

Our working paper addresses a second way that even parents with more moderate amounts of wealth are able pass advantages to their children. How? We look at the correlation in income between parents and the well-being of their children by parental wealth. We take the top 30 percent of wealthy parents and compare the outcomes of their children to parents from the bottom 30 percent of wealth and their children.

A child raised in a family with income in the bottom 10 percent and wealth in the bottom 30 percent ends up around the 29th percentile of the income distribution. In contrast, a child raised in a family with income in the bottom 10 percent and wealth in the top 30 percent ends up about 20 percentiles higher on average, around the 51st percentile of the income distribution. In today’s dollars, this amounts to $28,000 more in income, from $59,000 to $87,000, demonstrating the power of even moderate levels of wealth. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

High parental-wealth acts as a buffer for children raised in lower-income families by helping the children attain higher income as an adult. Families with higher wealth, for example, live in neighborhoods with better schools. Alternatively, higher wealth parents send their children to private schools, or the parents pay for college.

For children growing up in higher-income families, high parental-wealth acts as an accelerant to the already high parental-income, creating a double advantage for these children. We find similar results for the correlation between parental consumption and child consumption when they grow up.

The importance of wealth, and lack of wealth, also can be seen by comparing that low-income but high-wealth family to a high-income but low-wealth family. A child born to the top 10 percent of income but the bottom 30 percent of wealth ends up around the same place—around median income—as an adult when compared to a child born to the bottom 10 percent of income but top 30 percent of wealth.

The same basic story holds true for consumption. A child born to the top 10 percent of consumption but the bottom 30 percent of wealth ends up 10 percentiles lower in the consumption distribution as an adult when compared to a child born to the bottom 10 percent of consumption but top 30 percent of wealth.

Thus, this wealth inequality harms economic growth by giving advantage to the children of those with high wealth regardless of the parents’ income or parents’ consumption. These disparities in income, consumption, and wealth lead to the so called “lost Einsteins,” or children unable to meet their potential as adults, which hampers overall U.S. economic growth and further exacerbates economic inequality across income, wealth, and consumption.

End Notes

1. Based on authors’ calculations using the American Community Survey 2021 Five-Year File from IPUMS-USA. Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Matthew Sobek, Danika Brockman, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, and Megan Schouweiler. IPUMS USA: Version 13.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2023, available at https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V13.0.