U.S. economic policymakers need to fight the coronavirus now

The human tragedy of the coronavirus is now here in the United States. Nine deaths from the coronavirus have been reported in Washington state so far. Each day, more and more people are falling ill. Tragically, some will die; many others will recover but very well may spread the virus further. Quarantines are likely to be widespread.

The coronavirus is first and foremost a public health crisis. The front lines are the women and men who work at hospitals, community health centers, and pharmacies across the country. Each of us can contribute when we check on our elderly neighbors, make sure our children wash their hands (for 20 seconds with soap!), and take precautions to stay healthy and calm.

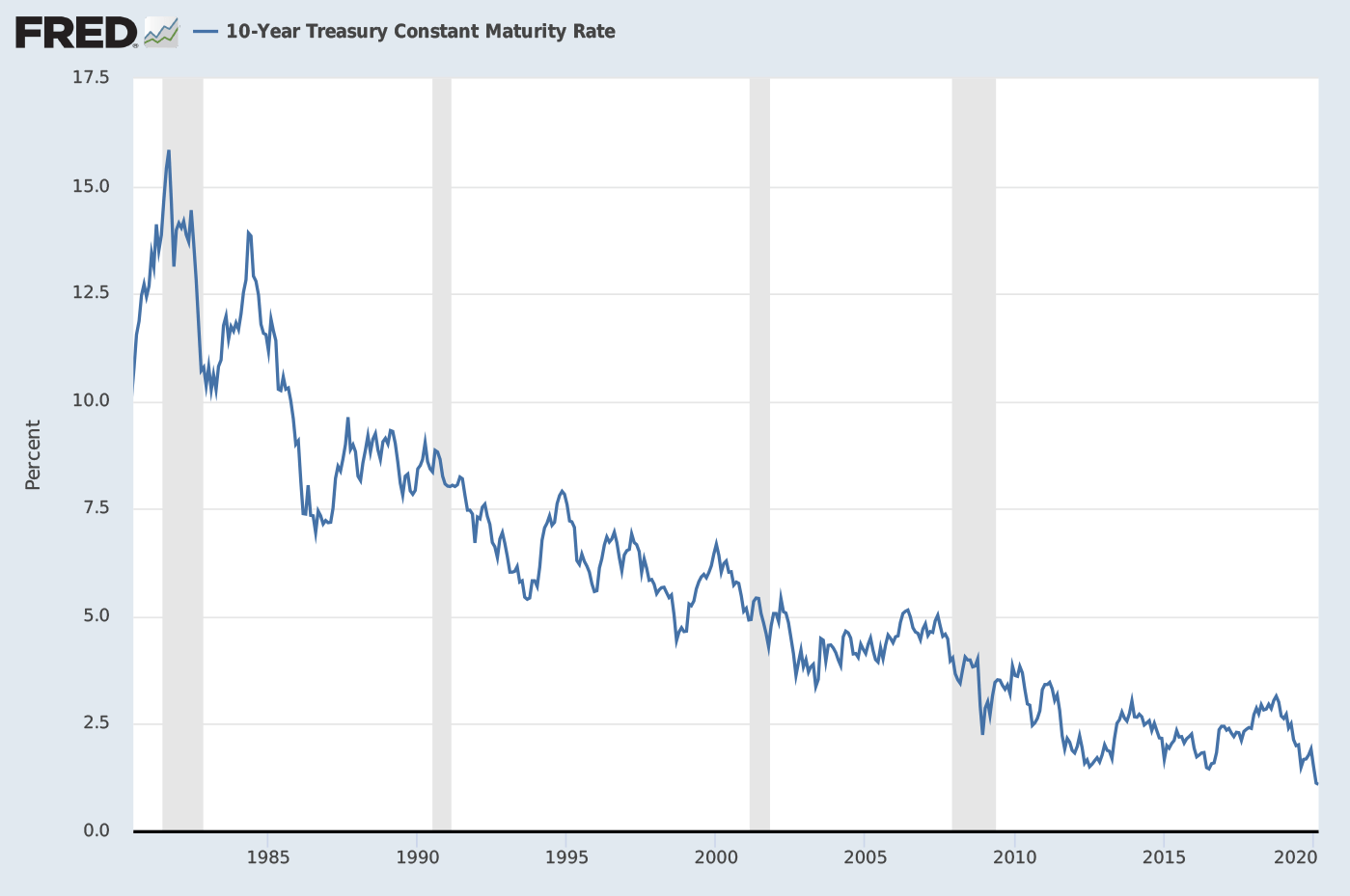

The coronavirus is a threat to our economy, too. We are starting to see it here, at the 26,000-feet (and falling) view of our volatile financial markets displayed in our living rooms, on our mobile phones, and on TVs in barbershops across the country. Last week, stocks plunged 11 percent in a single week—the most rapid correction ever. The yields on 10-year Treasuries, a benchmark interest rate for mortgages and other loans in the United States, are now less than 1 percent—the lowest level on record. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Long-term interest rates in the United States fall to lowest level on record

Daily yields on 10-year Treasury bonds, percent change, 1960–2020

Low interest rates are good for many people, businesses, and local governments. If they need to borrow money, they will pay less in interest and can generally get a better deal from lenders. Here, the Fed is helping push interest rates lower. In fact, lowering rates is its primary way to provide support during tough times.

Indeed, at times like these—when uncertainty is high and misinformation rampant—lower interest rates are a sign of potential trouble. Unrest in financial markets is the primary reason why interest rates and stock prices are falling. When the Fed cuts rates, it is trying to support the economy and calm financial markets. The Fed does not control the market; it plays an important supporting role. So, why are interest rates hitting all-time lows? Investors around the world are buying up the safest assets available—U.S. Treasury bonds. Unless the government sells more Treasuries, their price—referred to as the yield—will continue to fall. The flight to safety today is a flight from the economic consequences of the coronavirus.

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve acted decisively. It cut the federal funds rate 0.5 percentage points. That may not sound like much, but it is a bold move from an institution known for its caution. As of last Friday, it said in a press release that it was “closely monitoring developments.” No word of a rate cut then. And it cut almost two weeks before its next regular meeting.

The Fed decided two weeks was too long to wait. Its decision to act outside of a meeting in Washington was not business as usual. Moreover, it acted a mere three hours after a phone call with central bank leaders and financial ministers across the globe. An hour later, Fed Chair Jerome Powell held a press conference to explain the decision

Can the Fed do it alone? No. Its policy tools, such as cutting interest rates, are too blunt to help the people who need it most. People in our country are getting sick, and the most vulnerable workers could lose their jobs if they are too ill to show up. Monetary policy cannot address this gaping public health problem. Yes, the Fed might calm financial markets some. Yes, the Fed might help businesses and borrowers who are taking on debt. The Fed is doing its part, doing what it can. But it needs help.

Chair Powell made that clear before the cameras, saying:

The virus outbreak is something that will require a multifaceted response. And that response will come in the first instance from healthcare professionals and health policy experts. It will also come from fiscal authorities, should they determine that a response is appropriate. It will come from many other public- and private-sector actors, businesses, schools, state and local governments. But there’s also a role for monetary policy.

And again, saying:

You saw this morning’s G-7 statement of finance ministers and governors. I think that statement does reflect coordination at a high level in a form of a commitment to use all available tools, including healthcare policy, fiscal policy, and monetary policy as appropriate. So, in terms of fiscal policy, again not our role, we have a full plate with monetary policy, not our role to give advice to the fiscal policymakers. But you saw the mention in the G-7 statement as appropriate as well.

It is not Chair Powell’s job to tell the president and Congress what to do. Even so, his words are as close as a Fed official gets to sending out the “Bat Signal” and begging for a fiscal response.

So, what can the federal government do? Here is my proposal, grounded in more than a decade of research and forecasting at the Fed.

- Act fast. It is time for the federal government—all parts of it—to move swiftly against the spread of the coronavirus and any economic distress it may cause. If it acts now and joins the Fed in fighting back, the economic consequences will be less severe. We could spare the country from the worst possible outcomes. People and businesses would know that the government has their back and will do whatever it takes to end this crisis. The Great Recession taught us a painful lesson: Policymakers waited too long and were far too timid when they did act. Our country is still paying for those mistakes. It’s time to act. Go big or go home.

- Provide financial support to people who are suffering. Any person who has the coronavirus, is quarantined, or stays home to care for a loved one needs financial support immediately. The federal government should send them money—a check for $1,000, all at once, not $70 a week. The U.S. Treasury and regulators can also push banks to give people grace on their mortgages, credit card debt, and student loan payments. If that does not work, then give people directly affected a zero-interest rate loan until they are back on their feet. With interest rates at historical lows and demand for safe assets, it will cost the federal government very little to issue more bonds to pay for this program. Do it now.

- Plan for the worst. The U.S. economy is strong today—thankfully, it was strong before the coronavirus. The global economy was not. The U.S. unemployment rate is at a half-century low. That does not mean that our economy is immune to a pandemic. Congress and the Trump administration must follow the Fed’s lead and prepare for the worst. Everyone is monitoring the fast-moving events. They must be ready to go. Even better, get ahead of economic fallout and act now. To be most effective, policymakers need to coordinate their actions in public health and economic aid. The federal, state, and local governments need to talk and work together. Cooperation has yielded big benefits in the past. We need that today.

- Have automatic support ready for a recession. A recession occurs when consumers and businesses across the country pull back on spending and when production falls widely. We are not in a recession today, and the financial distress may end up being concentrated in particular regions of the country and not push the entire U.S. economy down. But again, we need to be ready. As soon as the national and local labor markets weaken, support from the federal government needs to start. In any recession, send money directly to people, as soon as the unemployment rate jumps. Other excellent ideas are to send support to states, increase support to the unemployed, and make supplemental nutrition assistance more generous. Do not target it to people who still have jobs, as a payroll tax cut would do. Get the money out to as many people as possible and as fast as possible.

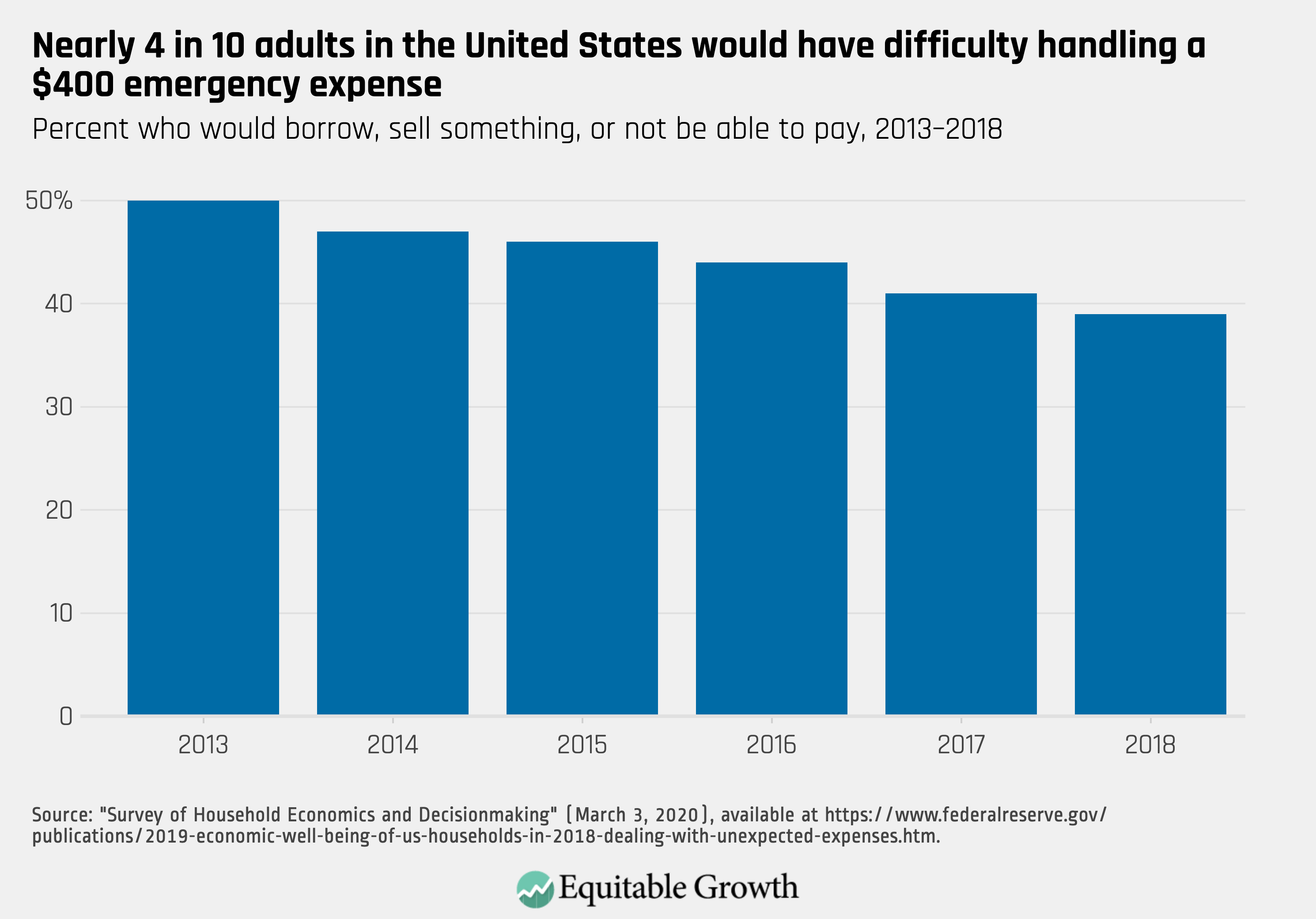

U.S. policymakers can beat the coronavirus, but it will take a rapid healthcare response and bold economic policies. We have no choice. Too many Americans are one paycheck away from financial catastrophe. Four in 10 U.S. adults tell us that if they had a $400 emergency expense, they would have to borrow, sell something, or would not be able to pay it. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Only 1 in 10 adults say they could not pay the expense by any means. But that expectation does not account for the consequences of that adult, or a family member, or co-workers, coming down with the coronavirus. Someone out of work for a week due to the pandemic would very quickly come up $400 short. Borrowing, trying to sell something, or picking up odd jobs is not how we want people to deal with this public health crisis.

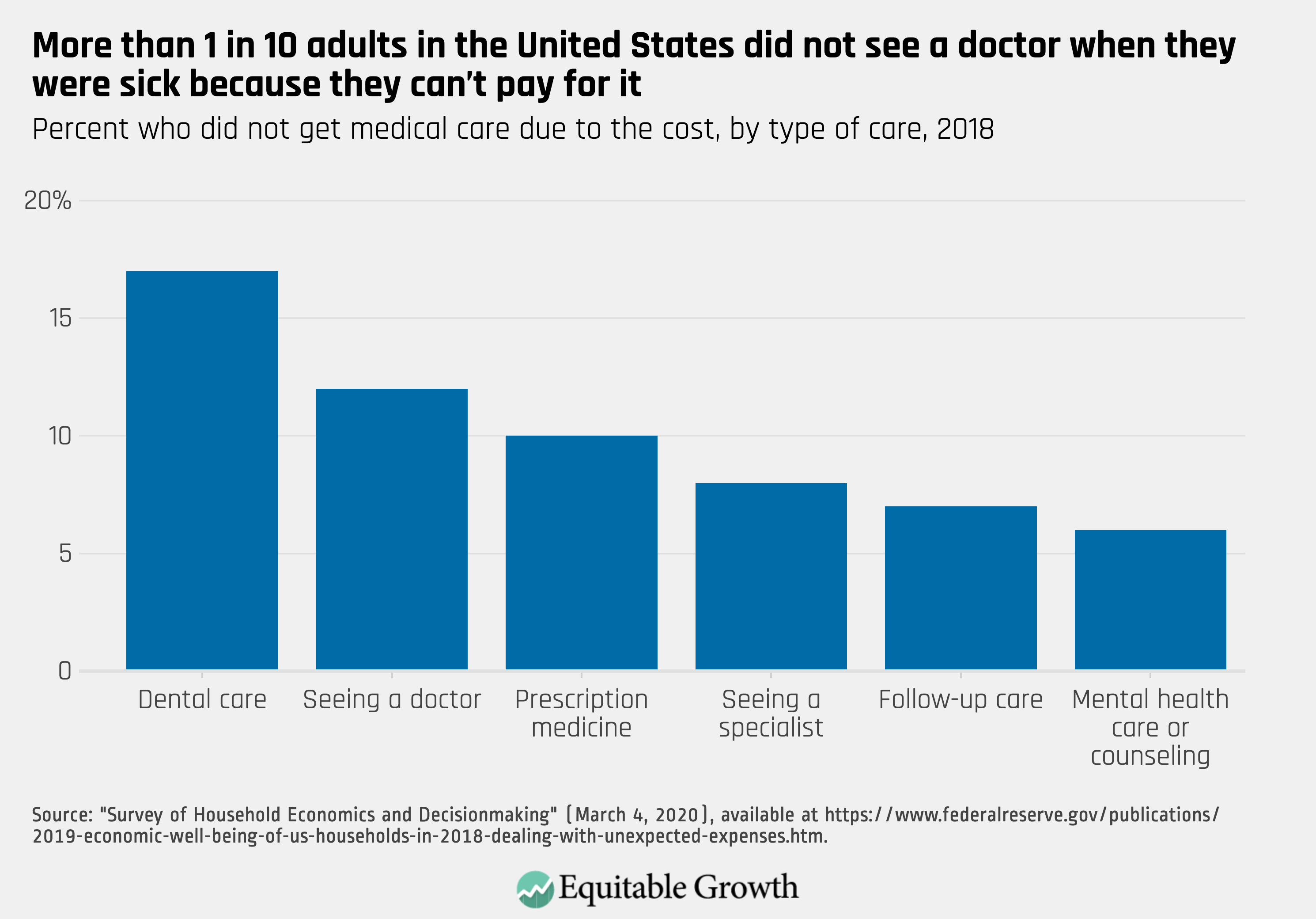

If the federal government does not give people financial support now, then we most certainly risk a worse public health crisis. Many people have so little savings that they regularly do not get the medical care that they need. In 2018, one-quarter of adults said that they or a family member went without some form of medical care because they could not pay for it. More than 1 in 10 skipped visiting a doctor in the past year when sick. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The coronavirus is highly contagious. If people cannot afford to go to see a doctor, they could get very sick and they might also spread the coronavirus to others. The federal government needs to give people the financial support they need to get healthy, stay healthy, and keep their family and co-workers healthy. This is a public health crisis—all arms of the federal government need to take coordinated action now.