The Economic State of the Union in 2022, presented in 11 charts, and what policymakers can do to make the recovery more equitable and resilient

Today, President Joe Biden will give his State of the Union Address, approximately 1 year into his administration and 2 years after COVID-19 struck the United States.

The coronavirus recession was incredibly severe. As the pandemic hit, the U.S. unemployment rate skyrocketed from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent in February 2020 to a post-Great Depression high of 14.7 percent in April of that same year. Over those same two months, the country’s employment collapsed. The U.S. labor market shrank by more than 20 million jobs. Industrial production plummeted. And the U.S. economy contracted by 3.4 percent over 2020—the worst year for economic growth since 1946.

The coronavirus recession officially ended in April 2020, but the federal policy response extended well into 2021 to ensure a robust economic recovery. By the end of 2021, real U.S. Gross Domestic Product growth hit 5.7 percent. Below are 11 charts that showcase the trajectory of our economy over the past 2 years and the important policy decisions that are still up ahead:

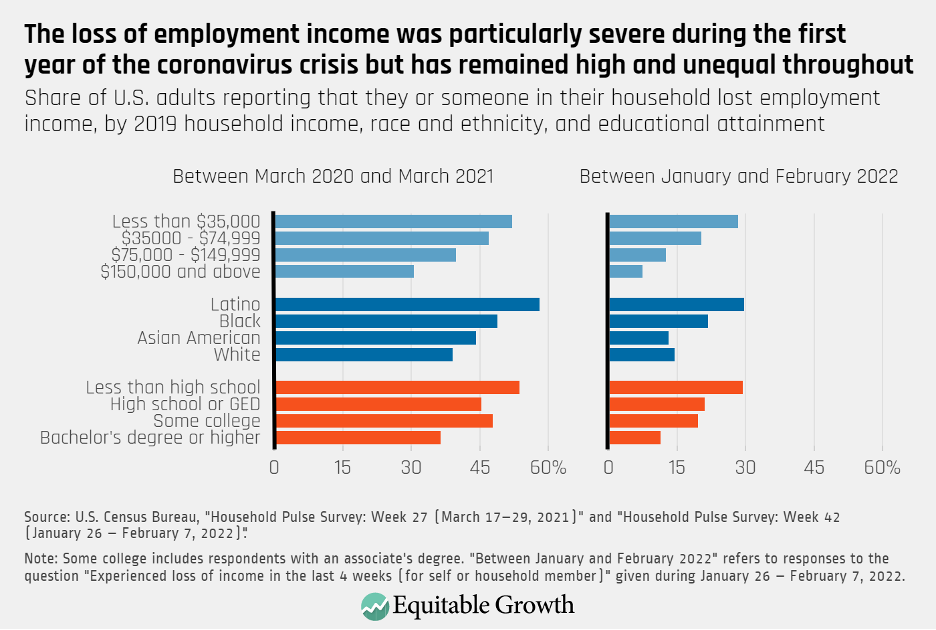

One of the most telling features of the coronavirus recession and continuing pandemic is that it hit already vulnerable groups especially hard. Both in the first year after the onset of the recession and in early 2022, lower-income households, Black and Latino households, and those with lower levels of formal education experienced especially large losses in employment income. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

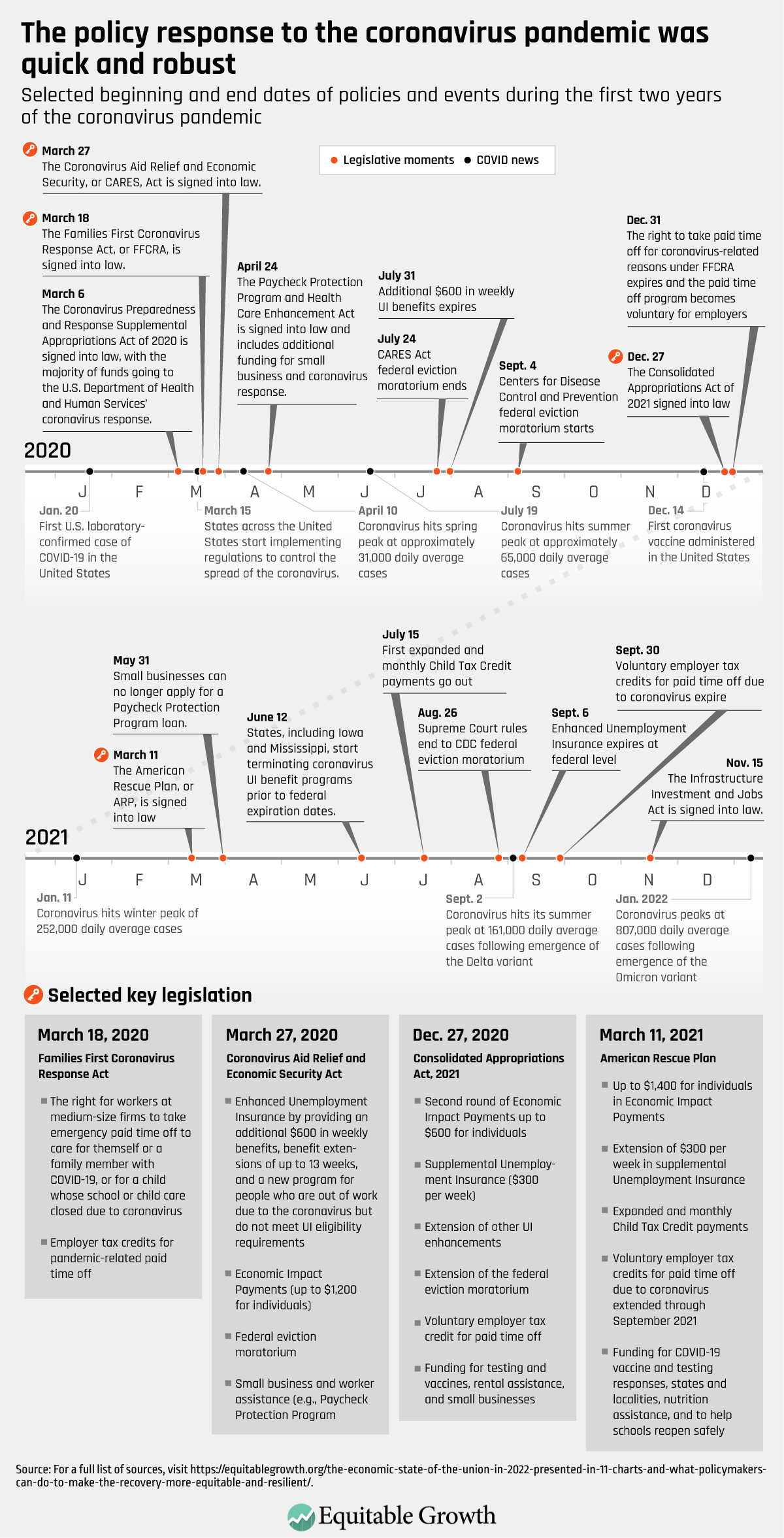

In response, the U.S. government enacted a series of measures shortly after the pandemic hit to mitigate the effects of the health and economic crises. Between March and April 2020, the U.S. Congress passed four major pieces of legislation, the most consequential being the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. The CARES Act included provisions to expand eligibility and provide extra support through the Unemployment Insurance system, additional funding for food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, loans and guarantees for small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program, and Economic Impact Payments.

The next year followed with the American Rescue Plan, signed into law in March 2021. It included an extension of many CARES Act programs as well as new initiatives such as the expansion of the Child Tax Credit. Provisions included in these bills began to expire in the first year of the pandemic and through 2021. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 21

The unprecedented speed and size of the policy response helped millions of workers and households withstand the economic pain brought on by the coronavirus pandemic. The bounce back in Gross Domestic Product, for example, was much quicker in the United States than in most other high-income countries; the aggregate unemployment rate is now close to its pre-pandemic level; and workers in the bottom of the wage distribution are experiencing real wage growth.

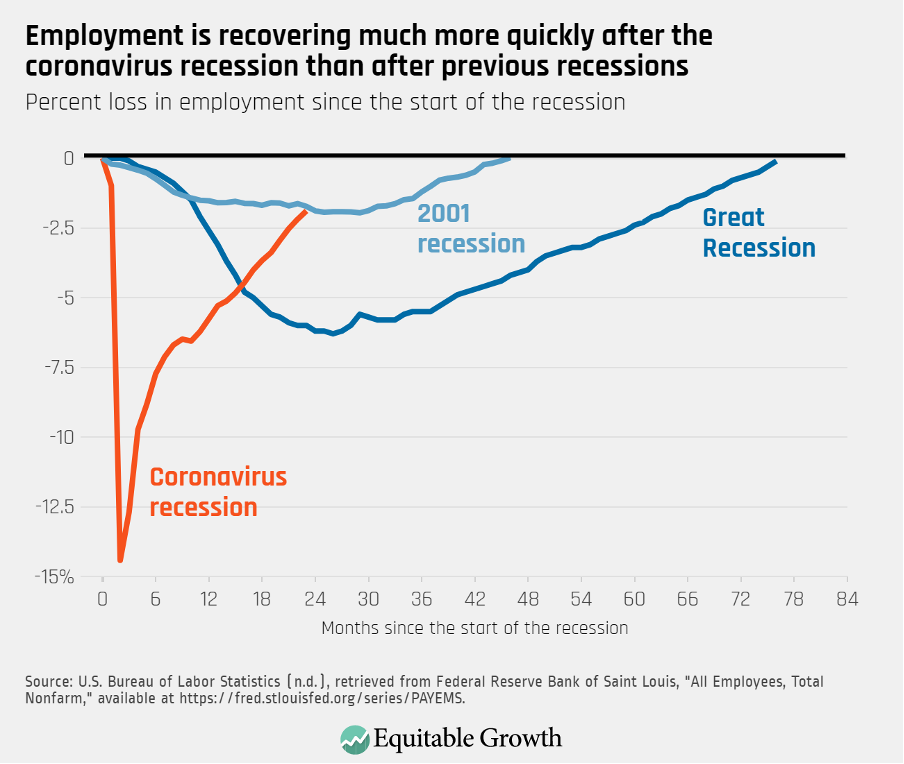

Indeed, the recovery in overall employment has been extraordinarily quick compared to previous U.S. economic downturns. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Yet the crisis shed light on the systemic inequities embedded in the country’s economy. These inequities include racial and ethnic disparities in access to income supports, big burdens on mothers and other caregivers, and vulnerability to health risks and worse conditions on the job, particularly for workers in low-wage positions.

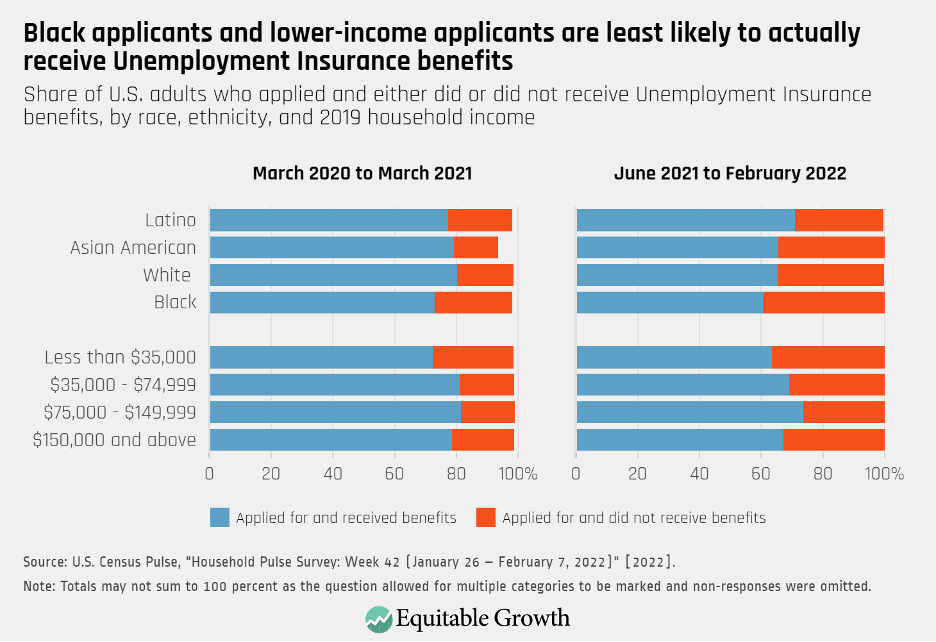

For instance, lower-income workers have been least likely to successfully apply and receive jobless benefits throughout the coronavirus crisis. Both in the coronavirus recession and the previous Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its aftermath, Black workers were among the least likely to access Unemployment Insurance benefits. Though differences in application behavior play an important role in shaping these disparities, even conditional on application, regular Unemployment Insurance eligibility criteria systematically disadvantages workers with shorter job tenures, unpredictable or insufficient hours, and lower wages—workers who are also disproportionately workers of color. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

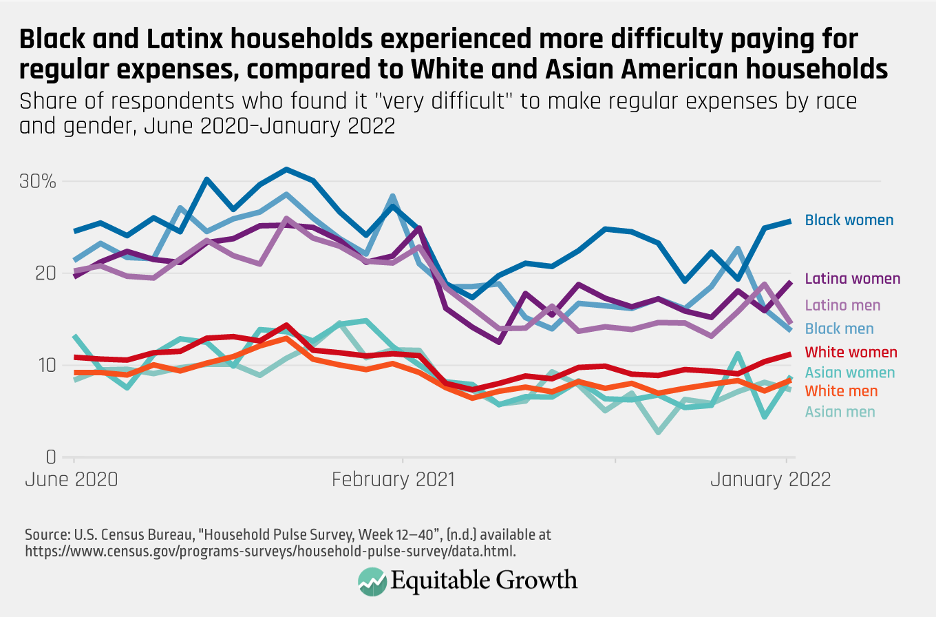

Two years after the onset of the coronavirus recession, disparities are stark and many workers, families, and communities are still hurting. Throughout the pandemic, Black and Latina women have faced the greatest difficulty paying for their regular expenses. Additionally, the interaction between gender and racial wage divides—or what Equitable Growth’s President and CEO Michelle Holder refers to as “the double gap”—have been exacerbated in the pandemic, as data shows Black women earn less than White men within the same frontline essential occupations. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

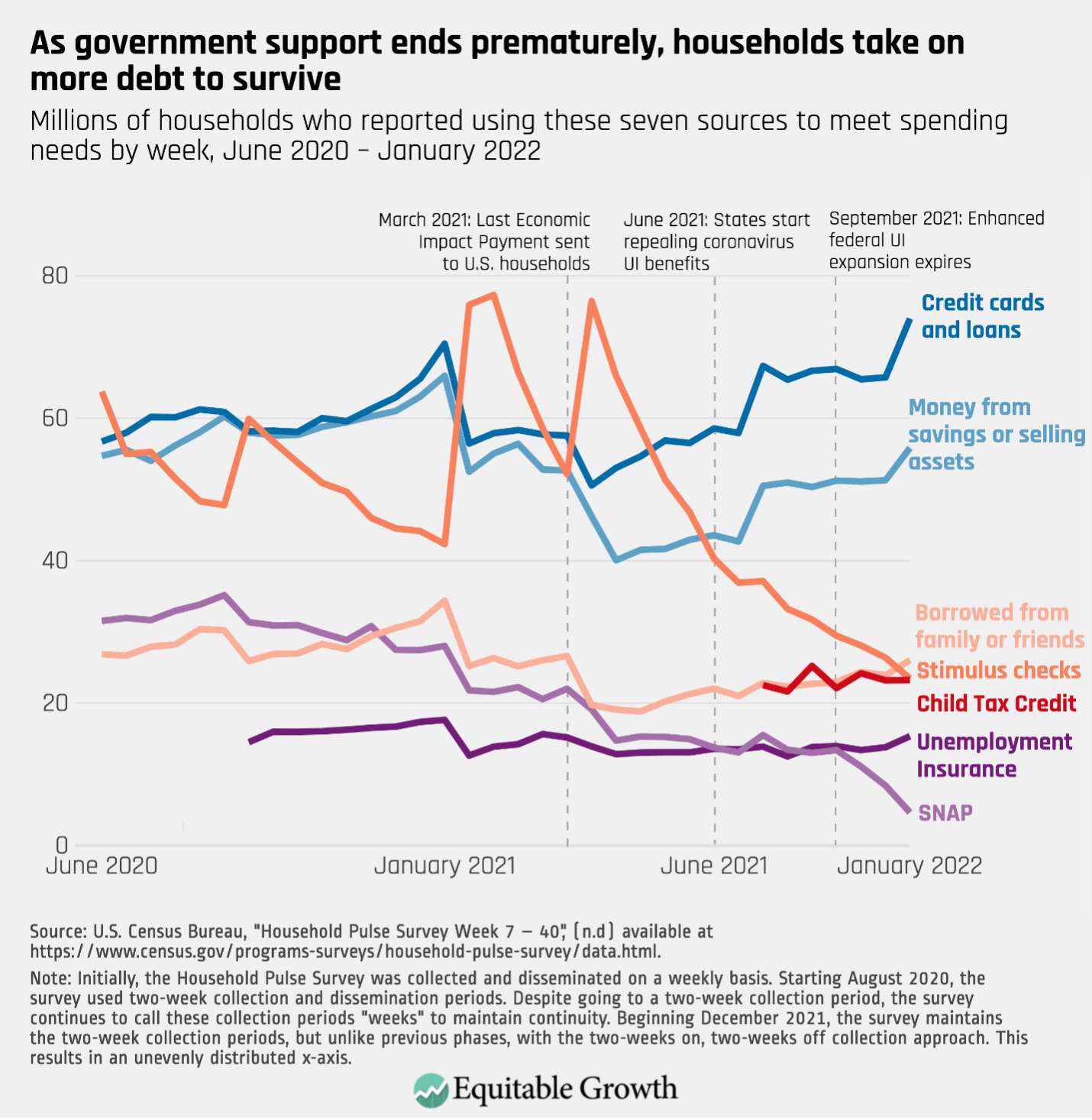

Moreover, many types of income supports were taken away prematurely, hurting many and especially those already disadvantaged. The result? Many workers, families, and communities are in serious danger of being left behind amid the current economic recovery. Data show that as households depleted their Economic Impact Payments, they began turning to credit card debt, loans, borrowing from friends or family, or selling off assets in order to meet regular expenses. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

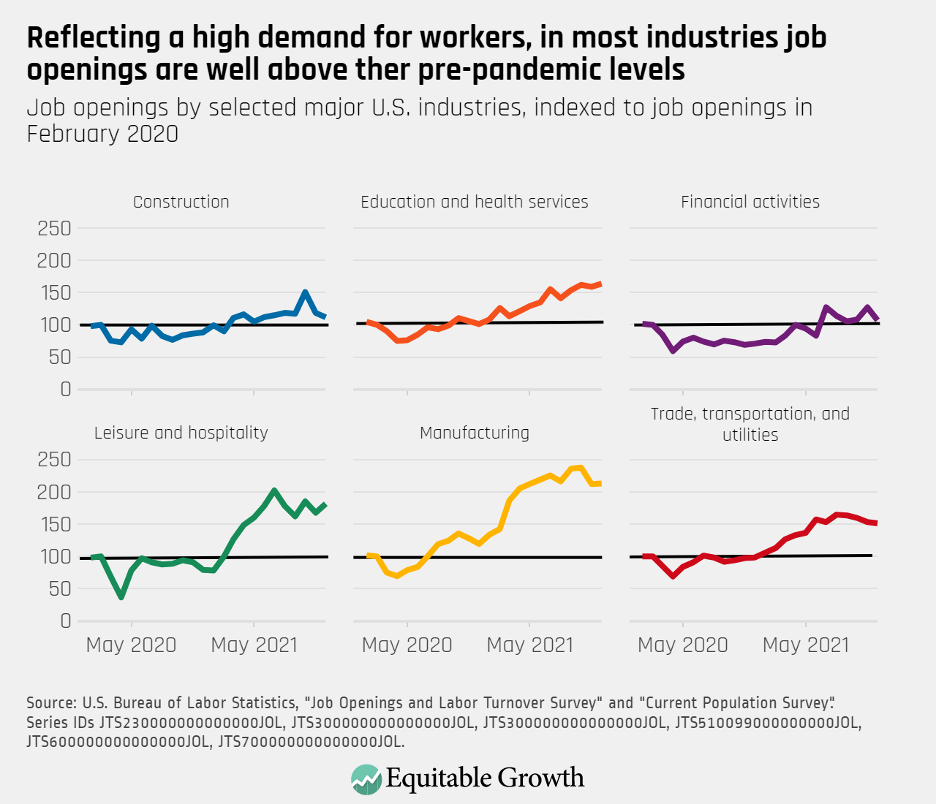

Fast-forward to today. A wide-range of indicators reveal a nuanced story about the health of the U.S. economy. On one hand, coronavirus cases are now well-below their early January 2022 peak, those at the bottom of the earnings distribution are seeing real wage gains. And labor demand has skyrocketed, giving workers more power to negotiate higher pay and better working conditions. As such, job openings in the U.S. reached a record high of 11.1 million in July 2021—an almost 60 percent increase from February 2020—and have remained elevated since. The jump in open positions has been particularly stark in industries such as manufacturing and leisure and hospitality. (See Figure 7.)

Figure 7

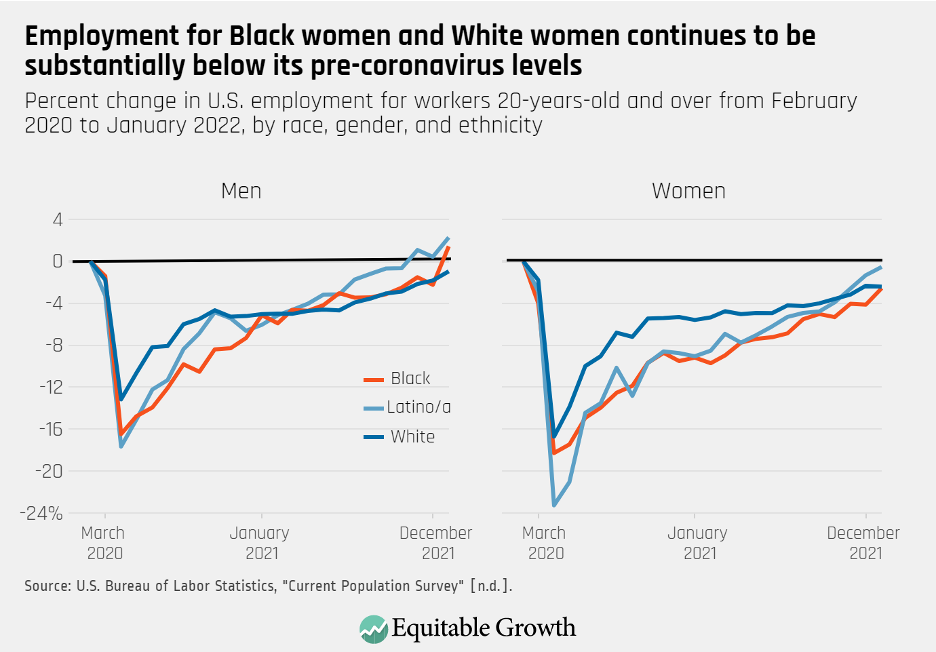

At the same time, the U.S. economy is still at a 2.9 million jobs deficit compared to February 2020. Both the effect of the health crisis and the recovery in the U.S. labor market have been uneven. For instance, employment levels for Latino men and Black men have only just risen above their pre-coronavirus levels, and other groups still have not recovered. Black women have experienced some of the toughest labor market outcomes, seeing the largest drop in labor force participation and the slowest jobs recovery. As of January 2022, 262,000 fewer Black women were employed than in February 2020—a 2.6 percent drop. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

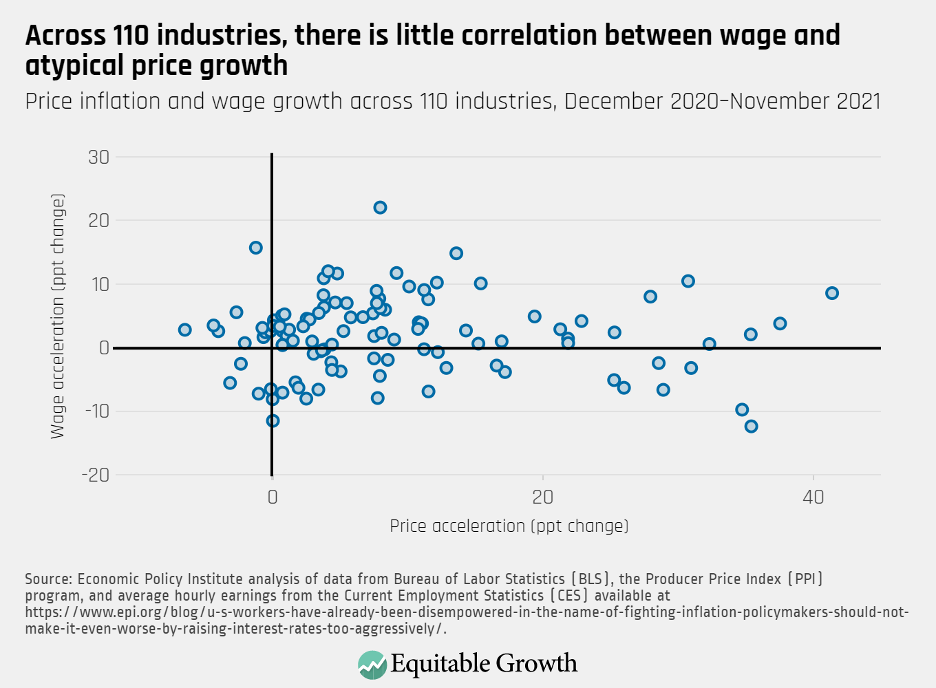

In the midst of it all, inflation has risen. Supply chain breakdowns due to the pandemic are a major reason. Yet some large firms continue to collect record profits, claiming that they need to raise prices for consumers to account for increasing costs of production, transportation, and labor. Many economists disagree. An analysis of price and wage growth across more than 100 industries by the Economic Policy Institute, for instance, shows that industries that increased wages to attract workers, such as hotels and other accommodations, have not seen an unusually large spike in prices. (See Figure 9.)

Figure 9

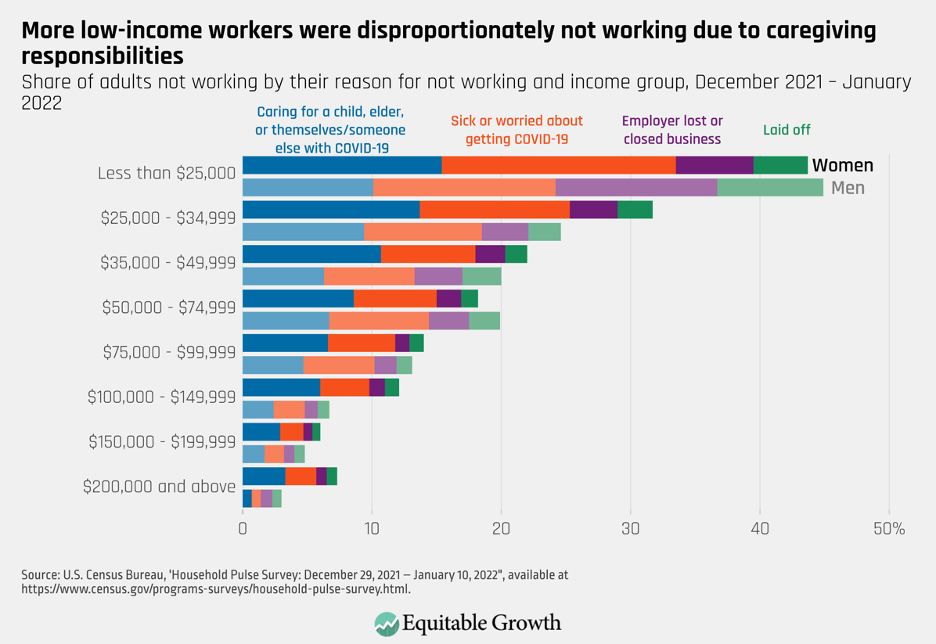

The notion that inflation warrants fiscal austerity is misplaced. Opposition to much needed government spending in social and physical infrastructure is holding back necessary reforms and investments. Under the weight of the coronavirus pandemic, the child care sector contracted dramatically, leaving parents scrambling to find the child care they need to return to work. Legislation such as the proposed Build Back Better Act would strengthen the labor market and allow parents to return to work knowing that their children are safe and well cared for. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10

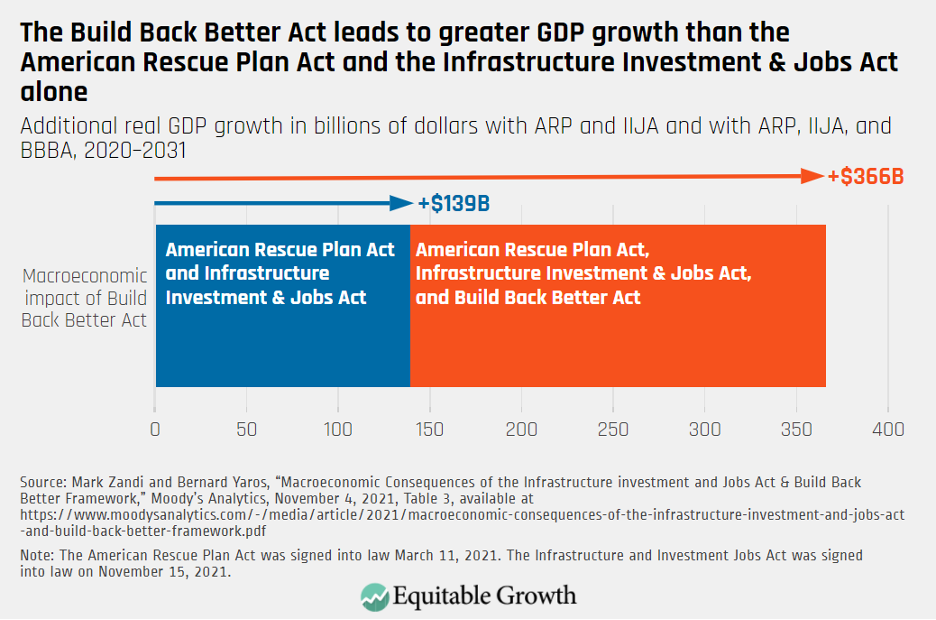

Swift and decisive government action caused the coronavirus recession to be much less severe than it could have been. Still, many households, particularly those headed by Black, Latino, women, or low-income individuals, are still reeling from the pandemic’s impacts on the economy. The Build Back Better Act contains many social and physical infrastructure proposals that are backed by economic evidence. One study finds that the full bill’s passage would increase Gross Domestic Product. By not passing the Build Back Better Act, policymakers would lose out on an opportunity to make the investments that could make the country’s economy more resilient and equitable. (See Figure 11.)

Figure 11

Conclusion

President Biden today is expected to reaffirm his commitment to enacting key parts of his Build Back Better plan. As these 11 charts demonstrate, decisive government investments in our nation’s social infrastructure remain key to overcoming endemic economic divides across race, gender, and income. With U.S. economic growth still strong, now is the time to make these investments so that the recovery is not just strong but also equitable and thus more enduring.

End Notes

1. Source: U.S. Center for Disease Control, “CDC Museum COVID-19 Timeline” (2022), available at https://www.cdc.gov/museum/timeline/covid19.html; Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, H.R. 6074, 116 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2020); Kavya Sekar and co-authors, “Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020 (P.L. 116-123): First Coronavirus Supplemental” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2020), available at https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46285.pdf; Families First Coronavirus Response Act, H.R. 6201, 116 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2020); Sarah Donovan and Jon Shimabukuro, “The Families First Coronavirus Response Act Leave Provisions” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2020), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11487; Molly Sherlock, “Payroll Tax Credit for COVID-19 Sick and Family Leave” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2021), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11739; U.S. Department of the Treasury, “About the CARES Act and the Consolidated Appropriations Act” (2021), available at https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/about-the-cares-act; The New York Times, “Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case counts” (2022), available at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html; Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act, H.R. 266, 116 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2020); Maggie McCarty and Libby Perl “Federal eviction moratoriums in response to COVID-19 pandemic” (Washington: Congressional Research Service, 2021), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11516; U.S. Department of Labor, “U.S. Department of Labor announces new guidance to states on Unemployment Insurance programs” (2021), available at https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/eta/eta20201230-1; Ben Guarino, “’The weapon that will end the war’: First coronavirus vaccine shots given outside trails in the U.S.,” The Washington Post, December 14, 2020, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/12/14/first-covid-vaccines-new-york/; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, H.R. 133, 116 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2020); American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R. 1319, 116 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2020); USA Gov, “Advance Child Tax Credit and Economic Impact Payments – stimulus checks” (2022), available at https://www.usa.gov/covid-stimulus-checks; Richard Cowan and Tim Ahmann, Reuters, March 16, 2021, available at https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-house-approves-small-business-paycheck-protection-program-extension-may-31-2021-03-17/; Julie Whittaker and Katelin Isaacs, “States opting out of COVID-19 Unemployment Insurance (UI) Agreements” (Washington: Congressional Research Services, 2021), available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11679; Adam Liptak and Glenn Thrush, “Supreme Court ends Biden’s Eviction Moratorium,” New York Times, August 26, 2021, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/26/us/eviction-moratorium-ends.html; U.S. Internal Revenue Services, “Under the American Rescue Plan, employers are entitled to tax credits for providing paid leave to employees who take time off related to COVID-19 vaccinations” (2021), available at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/employer-tax-credits-for-employee-paid-leave-due-to-covid-19; Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, H.R. 3684, 117 Cong. (Gongress.gov, 2021).