Realizing the promise of place-based economics requires more and better data from across the United States

A new report released today finds that access to opportunity in the United States varies by where people live and the color of their skin. The report, written by Ruth Gourevitch, Solomon Greene, and Rolf Pendall of the Urban Institute, uses data collected pursuant to the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule. HUD created the AFFH Data and Mapping tool, which combines data from a number of existing sources to describe access to opportunity at the neighborhood level, to allow communities to assess their current progress toward fair housing, and to set goals to achieve more equal opportunity for their residents.

The report reaffirms what scholars increasingly know to be true about economic outcomes in the United States: where a person lives shapes that person’s access to opportunity and his or her likely economic outcomes. The economist Raj Chetty at Stanford University has performed much of the foundational research in this new literature, showing that the neighborhood a child grows up in makes a lasting impact on that child’s future earnings. His recent work shows that innovation, measured by patent rates, is sharply different according to where inventors grow up, and that these patterns are not explained by innate ability.

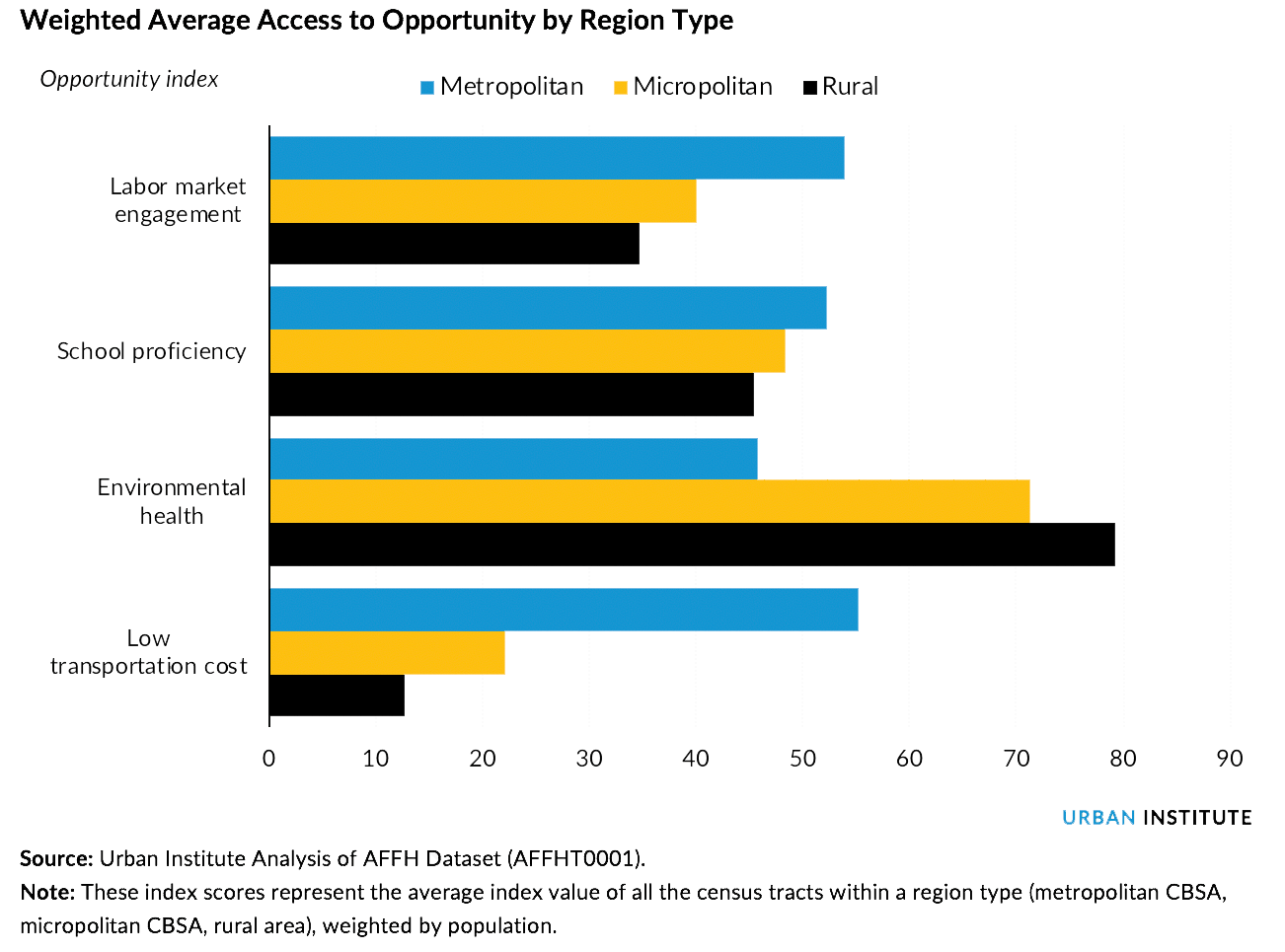

Likewise, the Urban Institute report shows that access to opportunity varies sharply for Americans according to whether they live in an urban or rural location, their race and ethnicity, and whether or not their income is above the poverty line. The full report is loaded with interesting graphs showing these results such as one that shows that Americans in urban areas are more likely to benefit from access to transportation and robust job markets but are disadvantaged by exposure to harmful toxins at the neighborhood level. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These findings probably aren’t surprising to most people who have a common-sense understanding of how different areas of the country are, well, different. But the ability to explore these trends in detail is a relatively recent phenomenon, enabled by new datasets and greater access by researchers to administrative data kept by federal and state agencies.

Additionally, economists have been reticent to recommend policy to confront disparities based on where people live and work. This reticence is based on the belief that market forces will encourage migration to more economically vibrant places, which will balance economic outcomes between, for example, rural and urban locations. But it is not clear that this balancing is actually happening in practice, which is why economists are coming around to the idea of targeting place-based disparities.

The recent pivot by researchers and policymakers to studying the economics of place is a welcome development. But this research is especially data intensive. If policymakers are serious about the promise of place-based policymaking, then they also need to be serious about collecting good data and making it accessible to researchers. The raw data behind the AFFH Data and Mapping program is a welcome tool and an example of the kind of data collection and data assembly that should be pursued more at the federal level. (HUD has suspended the community assessment portion of the AFFH rule, but the data is still available.)

Most of the most important U.S. economic indicators are still reported at an aggregate level, which can be misleading as a barometer of economic well-being. Unfortunately, federal statistical agencies often have inadequate access to the datasets they need to disaggregate these statistics and report at the smaller levels of geographic aggregation. As the nature of the U.S. economy changes and we start to understand and explore the role of where people live and work in shaping economic outcomes, these problems should be addressed. As Michael Strain at the American Enterprise Institute noted in a recent interview on this site, a small investment in better data collection could have a big payoff.