How to stop a recession by strengthening income supports in the United States

Income support programs, such as Unemployment Insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, are powerful tools to deploy when the threat of recession looms and unemployment climbs. By providing income replacement to people experiencing job and income losses, these programs serve as automatic stabilizers for the broader U.S. economy and stop unemployment from spreading contagiously, blunting the pain of recessions.

Yet the United States has systematically disinvested in its system of income supports over the past several decades. This creates obstacles for workers to access programs or even understand eligibility rules, and results in low benefit levels for those who do figure out the system.

To weather the next economic crisis, and the ones after that, policymakers in the United States need to permanently strengthen the U.S. system of income supports. This column details why income supports are essential, especially during economic downturns, how the currently weak income support infrastructure harms workers, and why proactive solutions are better for stable and broad-based economic growth.

Income supports are essential, especially during economic downturns

During recessions, the U.S. system of income supports—composed of programs such as Unemployment Insurance, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and other programs described in the Text Box above—play two main roles. First, income supports help workers and families who experience temporary drops in income to make ends meet.

Equally importantly, they automatically stabilize the macroeconomy by maintaining spending and consumption levels despite higher unemployment rates. This means income supports inject more income into the U.S. economy as increasing numbers of people access them—without any action needed from lawmakers.

Without income supports, workers who lose their jobs also lose income. As a result, they cut back on spending, which means businesses in their communities lose revenue, which, in turn, may lead to further layoffs. Income support programs stop this vicious recessionary cycle. For every dollar the government expends on Unemployment Insurance, for instance, at least $1.70 circulates through the U.S. economy. Likewise, for every dollar the government expends on SNAP supports in a slow economy, $1.54 circulates through the economy. As these dollars flow through the broader economy, businesses maintain their profit margins and do not need to lay off more employees, quelling the recession.

The U.S. income-support system is weak, hampering its efficacy in countering recessions

Despite its importance, the income support system in the United States is weak. For income support programs to effectively combat recessions, they must have four key characteristics:

- Eligibility criteria should be inclusive, so that the program extends to as many people as possible who are likely to spend the income they receive.

- Application and eligibility verification processes should be simple, so that people can enroll quickly and are not deterred from participating in the program.

- Benefit amounts should be calibrated to facilitate the maximum amount of spending: high enough to meet the needs of program participants, but not so high that participants will save funds instead of spending them.

- Benefit duration should last long enough to meet the needs of participants until the economic outlook improves.

In other words, for income support programs to be effective countercyclical tools, they must be easily accessible to people who are in need of income, and they must provide enough income to meet the needs of program participants for as long as they need them.

Unfortunately, none of the programs in the U.S. income support system meet all four criteria. Looking across the wide range of income support programs, most are only available to specific subpopulations, such as people with disabilities, older adults, or families with children. Because these programs are so specifically targeted, they are not well-equipped to reach the broader group of people who do not have enough income to meet their basic needs and thus would be likely to spend the resources. This hinders the system’s ability to stabilize the macroeconomy.

Beyond narrow target populations, income support programs in the United States typically have onerous eligibility criteria. Workers can lose eligibility for the Supplemental Security Income program by getting married if their spouse’s income exceeds eligibility limits. Applicants can be deemed ineligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program if their work hours fall below 80 hours per month or if their family keeps a rainy day fund that exceeds $2,500 when combined with other household resources. Having earnings reported on a 1099 tax form instead of a W-2 can render a worker ineligible for Unemployment Insurance.

Not only do complex eligibility criteria restrict the number of people who can access benefits, but they also deter eligible people from accessing the support they need. For instance, 1 in 3 people who are eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit believe themselves to be ineligible.

And even if workers do qualify for benefits, most face burdensome applications and processes to maintain proof of eligibility. Initial applications often have confusing questions, require extensive documentation, and are time-consuming to complete. Even after initial eligibility is achieved, participants must recertify regularly to continue receiving benefits. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, for example, requires periodic recertification, for which program participants must complete an interview in addition to filling out paperwork and providing documentation. Unemployment Insurance recertification happens weekly or biweekly and can be completed by phone or online, but jammed phonelines and crashed websites can make this an impossible task.

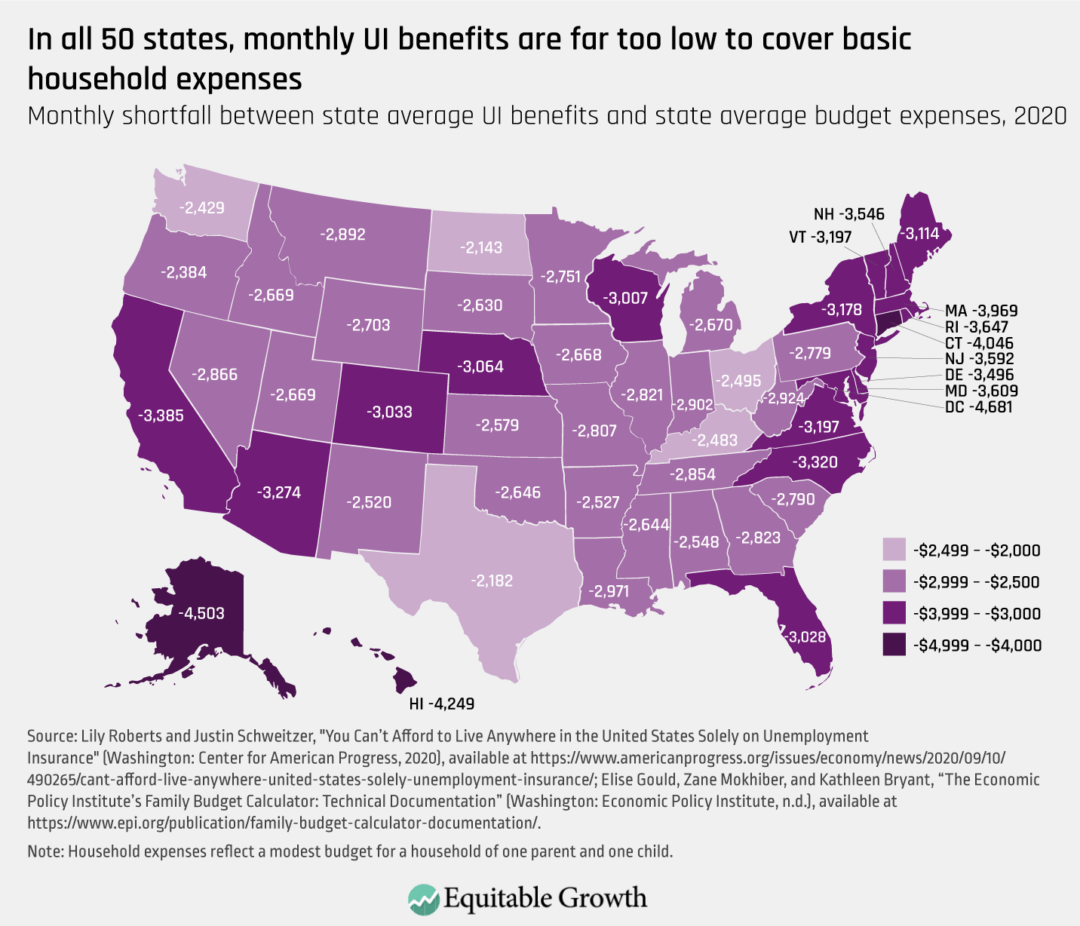

Then, for those workers who successfully navigate these hurdles, overall benefit levels are quite low. In every U.S. state, for instance, Unemployment Insurance benefit levels are far too low to cover one’s living expenses. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Similarly, in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia, benefit levels for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the program tasked with serving low-income families, fall well below the federal poverty line. In no state do they exceed 60 percent of the already-low federal poverty line, with the median benefit for a family of three being $498 per month. SNAP benefit levels are higher, with the average food assistance benefit to a family of three being $520 per month, but these dollars can only be spent on food. Supplemental Security Income provides $841 per month to low-income individuals with disabilities and $1,261 to couples. Even Social Security retirement benefits are low, at an average of $1,614 per month, or only 37 percent of the average retiree’s past earnings.

Simply put, no permanent income support program in the United States provides enough income to support a household’s full consumption needs. And even when U.S. families access multiple income support programs—for example, if they receive both TANF and SNAP benefits—they still struggle to make ends meet.

Many income support benefits also are time-limited. In many states, for example, unemployment benefits expire after just 16 weeks even if a worker’s employment status has not changed. Though there is a policy mechanism at the federal level designed to automatically extend the duration of UI benefits in tough economic times, it is broken.

Similarly, there are lifetime limits on access to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. In most states, families can only access the benefit for 5 years, but it is even less in 12 states. These time limits mean that even if people are likely to spend the income that they would receive through these programs, and thus stabilize the economy, the programs cannot serve many of them.

Across the U.S. system of income supports, eligibility criteria and application procedures screen people out of accessing benefits, and low benefit amounts and short durations put unnecessarily low caps on the amount of resources that can flow through these programs and stabilize the economy. In some cases, these barriers are so strong that they prevent the program from serving as an automatic stabilizer at all. Rigorous research did not uncover any statistically significant increase in TANF participation during the Great Recession, a pattern which appears to have repeated itself during the COVID-19 recession.

Relying on one-off solutions to temper recessions is a dangerous strategy

In the absence of a well-functioning, countercyclically responsive system of income supports, people in the United States must rely on one-time fixes enacted by policymakers in order to prevent and temper recessions using fiscal policy tools. Relying on these one-off solutions is an inefficient, and even dangerous, strategy. Not only does legislation take time to enact, delaying a response that should be immediate, but it also may be poorly targeted or even shelved entirely due to political considerations.

One of the most common tools used by legislators to stimulate or stabilize the economy is one-time cash payments to all households with income below a specified level, often referred to as “stimulus checks” or “economic impact payments.” During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, for example, households with incomes ranging from $3,000 to $150,000 were eligible for payments of up to $1,200 for joint filers, plus $300 for each dependent. During the COVID-19 recession, three rounds of economic impact payments were issued, with maximum benefit levels ranging from $1,200 to $2,800, plus $500 to $1,400 per child, for households with incomes ranging from $1,200 to $150,000.

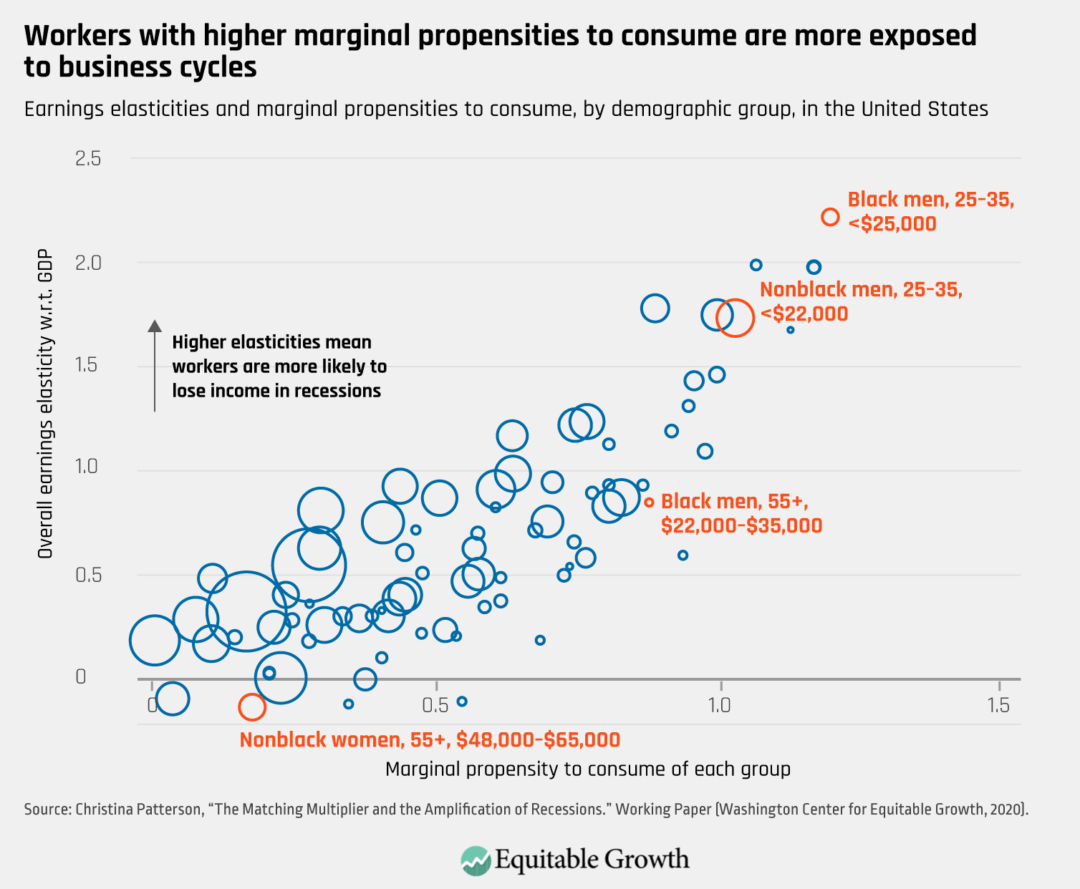

Overall, research suggests that one-time cash payments can help temper recessions. For every dollar spent on the first round of economic impact payments during the COVID-19 recession, for example, U.S. households spent between 11 cents and 66 cents. Yet stimulus checks are also less efficient than traditional income support programs, such as Unemployment Insurance and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Developed and administered quickly, one-time cash payments cannot be targeted to people who are likely to spend, rather than save, the payment. This is important because the macroeconomic benefits of maintaining consumption levels will not occur if income support is saved rather than spent.

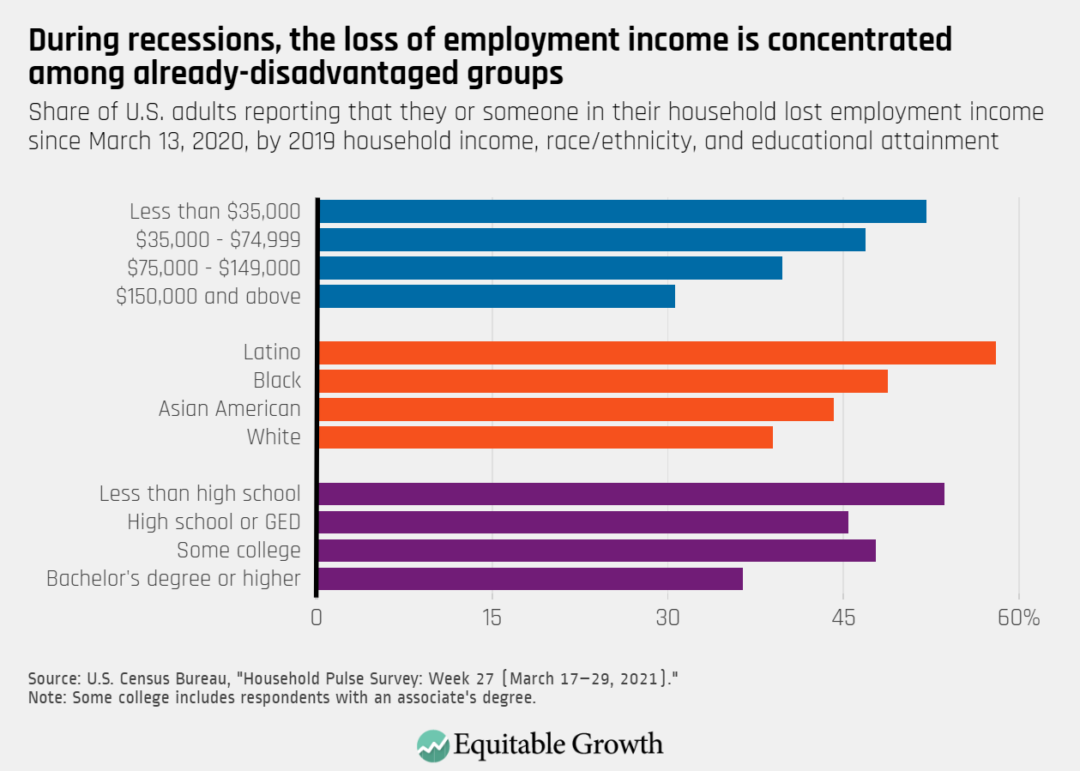

By contrast, permanent income support programs target people who have lost income or who have very low incomes and thus typically are more likely to spend the income they receive from these programs. People who lose income from work are likely to spend income supports they receive both because of their circumstances and because demographic groups who are likely to lose income in economic downturns are also generally more likely to spend new income than other groups. This is perhaps because these groups of workers have lower levels of savings due to the same structural forces—such as discrimination in the labor market and educational institutions—that make them likely to lose work or wages. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Yet, as described above, even the permanent income support programs that target people who are likely to spend income have serious flaws that dampen their ability to automatically stabilize the U.S. economy efficiently. To address these programs’ flaws, policymakers also typically rely on one-time solutions implemented during economic crises. During the Great Recession, Congress increased the duration of UI benefits in one-off extensions. And during the COVID-19 recession, Congress made radical, one-time changes—most prominently, by increasing the amount and duration of Unemployment Insurance and expanding its eligibility criteria, as well as enhancing the Child Tax Credit.

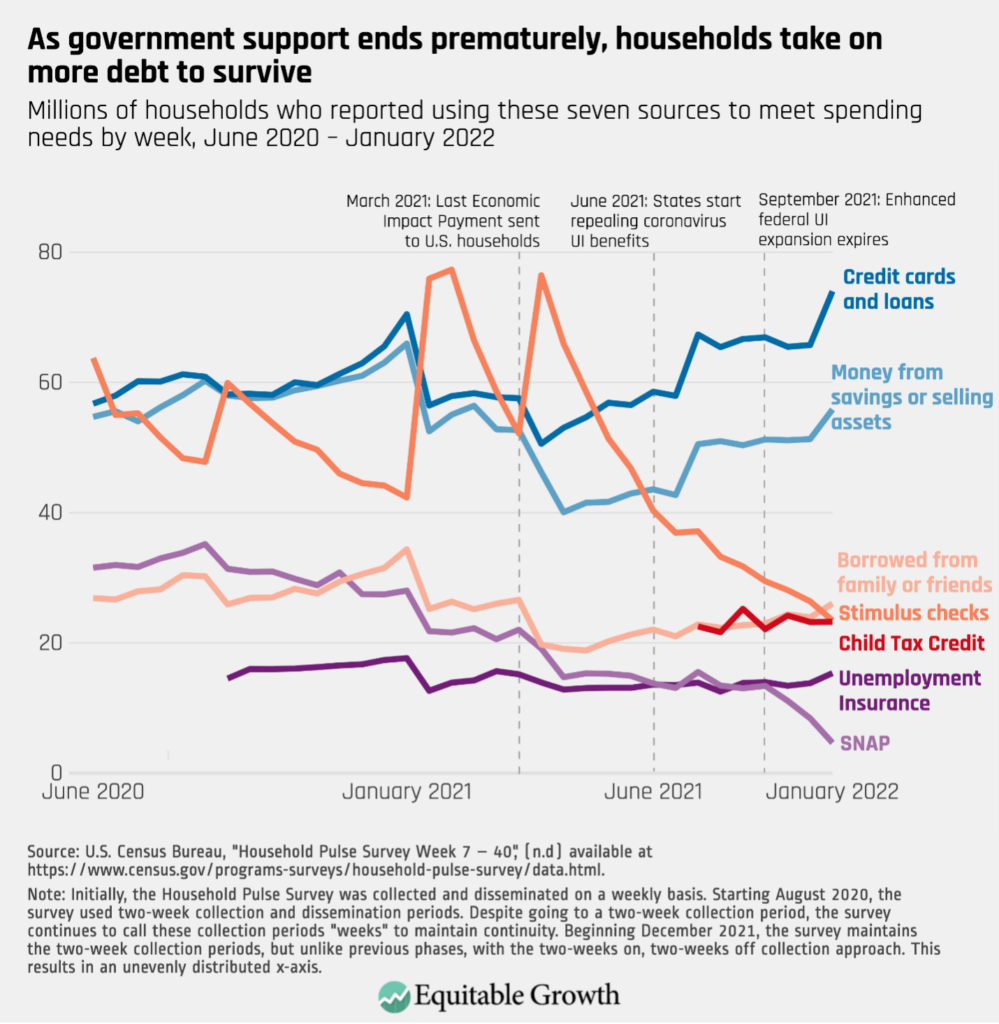

The political will to make these changes during the COVID-19 recession was unique and spurred by an unprecedented health crisis. Relying on political will, however, is a dangerous strategy. This is because political will may turn away from expanding income supports at moments when they are economically necessary tools.

One telling case in point: When political will shifted and the COVID-19 recession income support provisions began to expire, U.S. families suffered. The number of households in the United States that reported using credit cards and loans to make ends meet—a dangerous strategy for family economic security—increased when the temporary pandemic programs ended and left families with few options to pay their bills. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Permanent solutions will equip us for the next recession—and the ones after that

There is no guarantee that political will in the United States will align with economic reality, allowing policymakers to implement one-off solutions when another recession hits. If no action is taken, then families will feel the pain. People of color and those with low levels of income and education will suffer disproportionately, which will ultimately undermine our ability to minimize the duration and severity of the next recession. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

In economic crisis after economic crisis, U.S. policymakers are left scrambling to fight political battles and implement one-time fixes to the income support system. As of yet, policymakers have not acted on the lessons from previous crises to permanently strengthen the U.S. system of income supports. As it stands, the permanent system of income supports in the United States is not up to the task. Weaknesses make these programs difficult to access and prevent them from providing adequate resources to meet the needs of U.S. families, hampering the ability of these important programs to automatically stabilize the macroeconomy when recession hits.

With the threat of a potential recession looming anew today, and with the memory of the most recent economic crisis fresh in the minds of policymakers and the public, now is an opportune time to strengthen the U.S. system of income supports to be prepared for the next crisis. By making eligibility criteria more inclusive, programs easier to access, and benefit amount high enough and duration long enough to meet the needs of program participants, the income support system can be ready to automatically stabilize the economy when economic contraction first begins.