A place-based economic development strategy to foster rural U.S. prosperity

Overview

Whether one lives in a city of 2 million people or a town of 2,000, we all want to live in healthy and thriving communities, to have the chance to move forward in life, and to be free from the worry about “just getting by.” That is why it is important for policymakers to have a strategy for investing in rural areas of the United States.

The prevailing myths that persist around rural America can distort policy choices, however, making it difficult to secure both public and private investments in rural places. Economic growth thus can elude these communities, even as the national economy grows. This, in turn, can lead to resentment among rural residents, which right-wing populists may exploit as they seek to vilify the people in power.

A place-based strategy for investing in rural America calls for using data and building capacity within rural communities to develop their existing assets so they can better plan and manage their future economic growth. This strategy would help federal policymakers center rural places when developing policies, while at the same time offering a counterweight to the rise of right-wing populism by giving the residents of rural communities voice and agency to determine their paths to prosperity.

This essay details how a three-pronged, place-based strategy to spur economic growth in rural communities across the country boasts proven success stories in recent years. But first, I will address the myths about rural America that get in the way of effective economic policymaking, then present the facts about local rural economies and the models for successful rural economic development. I close with two salient examples of public-private partnerships investing with success in distressed local economies in eastern Kentucky and northwestern Mississippi.

These are just two examples of viable roadmaps to support place-based rural economic development. These models can be used across the nation to bring the assets and aspirations of rural Americans into the economic policymaking process by giving them agency to lead economic development in their own communities.

Misplaced myths about rural America today

Rural areas, which exist in every state of the union, are vibrant and diverse.1 Not surprisingly, this description often runs counter to the prevailing view of rural America. Several myths about rural America dominate this narrative, painting a misleading and limiting picture.2 Let’s first highlight three prevailing facts about these communities.

Rural counties are racially diverse

While White people do make up a larger share of the population in rural counties, the myths that rural America is all White and that communities of color live only in urban areas do not hold up.3 African Americans represent 7 percent of the population in all rural U.S. areas, but they make up nearly 16 percent of the rural population in the South.4

Rural economies depend on jobs across a variety of sectors

Agriculture is important in rural counties, but other sectors—including government, manufacturing, retail trade, and accommodation and food services—employ many rural workers. Indeed, 41 percent of rural jobs are in the service sector, while just 7 percent are in the agriculture sector.5 The recreation-related and accommodation and food services sectors have experienced the most job growth relative to other sectors in rural areas since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in May 2023.6

Many rural communities are thriving

This is particularly the case when it comes to entrepreneurship and the tech sector. Rural areas are worth investing in, contrary to beliefs that such investments do not pay off. There are many rural communities—among them Pine Bluff in Arkansas, Independence in Oregon, and Marquette in Michigan—where local communities are using existing technological infrastructure to build innovation hubs, strengthen entrepreneurship-support networks, and develop agriculture technology projects.7

Combating rural resentment through recognition of the value of place

For too long, both the public and private sectors have underinvested in rural communities because investing in these places was deemed inefficient and there is a belief that investments will not scale. This has led to these communities and their residents being unable to achieve their full potential.

This dearth of investment is one key reason for the rise of populism in rural communities because residents feel excluded from the policymaking process and believe their interests have been ignored by urban residents—and especially urban elites, who, by and large, misunderstand the economic realities and potential of rural America—creating a rural-urban divide. While this divide is not a recent phenomenon, the chasm that has developed has widened within the past decade in the United States.8

While rural areas have supported President Donald Trump at increasing levels in the past three presidential electoral cycles,9 this has not translated into policies that benefit these places. One of the current Trump administration’s first actions was to freeze funding that helps rural communities advance economic development initiatives, such as high-speed internet, clean energy investments, and climate-smart agriculture programs.10

While some of the funds were eventually released, the second Trump administration has continued its hostility specific to clean energy investments that benefit farmers and rural communities by cancelling application windows for the Rural Energy for America Program.11 This and other programs funded through the Inflation Reduction Act supported clean energy and energy efficiency upgrades that lowered costs for farmers, households, and rural small businesses.

In addition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced in July 2025 a reorganization plan that will cut staff in its Washington, DC offices by more than 50 percent and relocate them to five metropolitan cities throughout the country.12 During President Trump’s first term, the administration relocated two USDA research arms—the Economic Research Service and National Institutes of Food and Agriculture—which led to a significant exodus of employees and decimated those institutions.13 Combined with the existing cuts to the field offices in small towns throughout the country, this will further limit investments to rural U.S. communities.

To promote rural prosperity, policymakers need to embrace a comprehensive economic development strategy that relies on a proper accounting of rural America and the plethora of assets in these communities. This strategy can stem the rise of right-wing populism by affirming identities related to place through asset mapping and providing agency to communities through residents’ involvement in policy development and implementation.

This strategy recognizes that talent is geographically distributed, but opportunity is not. It targets the most distressed communities and helps policymakers recognize that all communities have assets. It gives voice to the residents of these communities, uses data and builds capacity to effectively target public- and private-sector investments, and provides a platform for philanthropic sectors to invest their dollars to partner with these communities.

Defining the economic well-being in rural America

Part of the lack of understanding of the realities about rural America is that there is no single definition of “rural.”14 In fact, various federal agencies use 12 different official definitions of rural areas. The two most common definitions, from the White House Office of Management and Budget and the U.S. Census Bureau, are based on whatever is not considered urban or metropolitan.

The Office of Management and Budget uses metropolitan status, while the Census Bureau uses population density within a specified geographic unit. Rural itself is undefined. This leads to significant struggles in rural communities often hidden from the larger picture of the national economy. Two telling statistics: 85 percent of counties with persistent poverty have entirely rural populations, and over the past 30 years, these counties have had a poverty rate of at least 20 percent.15 In many of these counties, the poverty rate has exceeded 20 percent for longer than that.

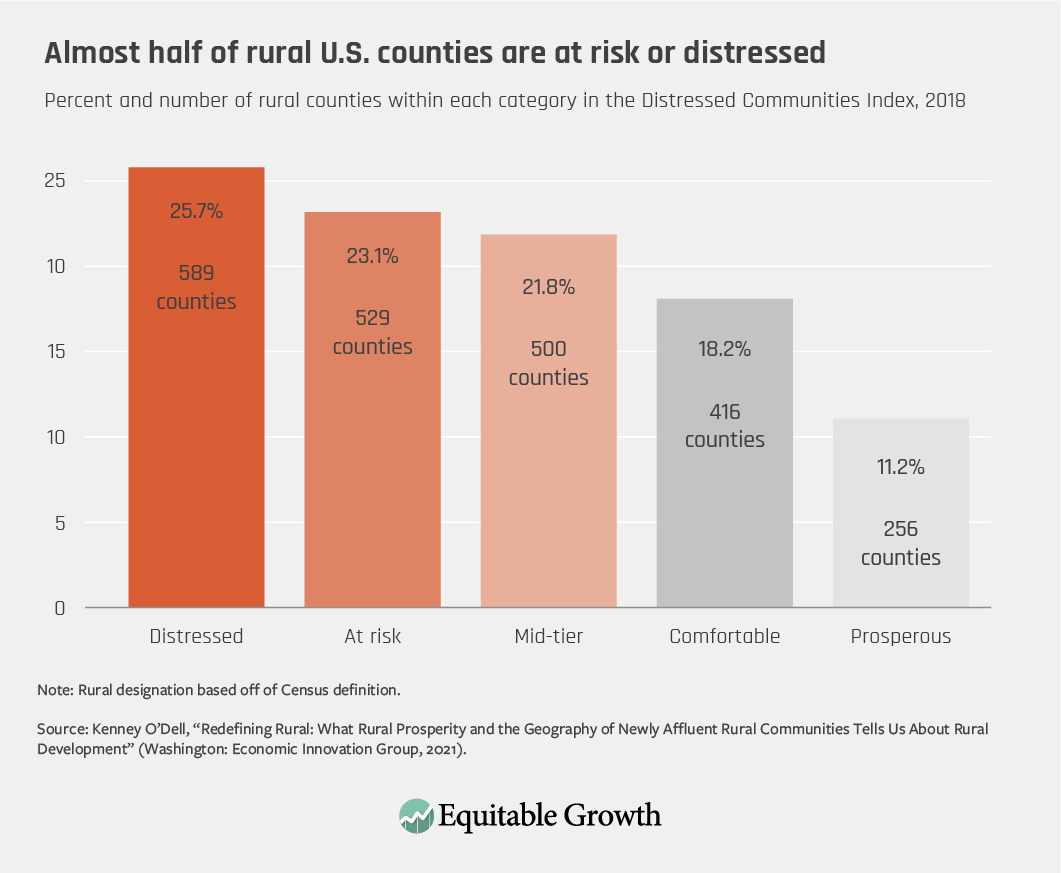

Rural communities score poorly on other measures of well-being as well. The Economic Innovation Group’s Distressed Communities Index relies on seven indicators to measure economic well-being, including:

- Educational attainment: The share of the population ages 25 and older without a high school diploma

- Housing availability: The share of habitable housing that is unoccupied

- Labor market vibrancy: The share of the prime-age population that is not currently employed

- Business creation: The percent change in the number of business establishments over the past five years

- Income levels: The median household income as a share of metro-area median household income

- Changes in employment: The percent change in the number of jobs over the past five years

- Poverty rate: The share of the population below the poverty line16

Based on the results, U.S. counties are sorted into five categories or quintiles. The top category is defined as Prosperous, followed by Comfortable, Mid-tier, At-risk, and finally, Distressed. As of 2018, roughly one-quarter of all rural counties—the greatest share in any category—are considered distressed. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Why there are so many distressed communities in rural America

The early 20th century saw the rise of industrialization, which led to the migration of many rural workers and their families from rural agricultural towns to urban cities.17 Then, during the late 20th and early 21st centuries,18 many U.S. firms relocated overseas, where they were able to take advantage of cheaper labor, affecting both urban and rural areas.

Consolidation in various industries amid this massive corporate offshoring led to the extraction of value—of both natural resources and labor—from rural areas,19 while diminishing labor market opportunities for rural residents. This consolidation led to a rise in what economists define as monopsony power (where an employer sets wages below a competitive market wage), and this further diminished labor market opportunities in rural places.20 Urbanization, along with globalization, led to lower demand for rural labor as employers looked elsewhere for higher-skilled labor.21

In addition, private capital seldom reaches these communities. Rural businesses receive less than 1 percent of all venture capital, even though 20 percent of the U.S. population lives in rural areas.22 Similarly, philanthropies direct just 7 percent of their spending to rural areas.23 Readily available capital has been further limited by the drop in the number of rural community banks, often forcing rural businesses to rely on personal savings to grow.

Then there’s the steady decline in the federal workforce devoted to rural America. Reductions in the federal workforce is now a salient issue at the start of the second Trump administration and the launch of its White House-based Department of Government Efficiency. Yet reductions and reorganizations at federal institutions focused on rural populations, such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture, have been ongoing since the Clinton administration and its National Performance Review initiative.24 This policy significantly reduced and continues to reduce the number of field offices of federal agencies, many in rural areas.

Population declines in certain rural areas,25 especially those communities that are more remote and not near a major metropolitan area, also contribute to challenges as lower demand for hospitals,26 schools,27 and grocery stores results in residents’ difficulty accessing needed services and, in turn, make these communities less appealing to potential residents. For those residents who do not or cannot leave, there can be a feeling of abandonment that steers blame toward policymakers.28

Taking all these factors together shows how the national economy has left many of these communities behind, opening the door for political support of right-wing populist ideals. Now, let’s turn to proven strategies to reverse these trends.

Reversing disinvestment in rural America

While many rural communities are struggling, others are doing well and some are beginning to experience prosperity. Between 2000 and 2018, several rural counties experienced budding prosperity, as measured by the Economic Innovation Group’s most recent Distressed Communities Index.29

Many of these counties are in the Upper Midwest and Northern Plains regions, both of which tend to be heavily involved in natural resource extraction. One example is the fracking boom of the early 21st century, though this industry is susceptible to boom-bust cycles.30 Other prospering counties include rural places that are part of a collection of growing exurban counties around metro areas, buoyed by population growth.31

So, let’s now look at how other rural communities could create paths to their own economic prosperity.

Place-based policy strategy

To help combat the disconnection that many rural areas have from the national economy, it is important to recognize the assets that exist in all rural communities and to develop place-relevant programs to leverage these assets. While some rural communities are more prosperous than others, every rural community has assets that make it worthy of investment.

One such asset is the people in these places who are talented and have ingenuity but do not have the opportunity to showcase it. Building off the Community Capitals Framework, which measures quality of life in communities,32 the Urban Institute developed a taxonomy of rural community assets that highlight the diversity of rural places.33 These assets include energy-rich areas, high-employment agricultural areas, areas with high civic engagement, areas with strong institutions (such as institutions of higher education and community facilities), and areas with natural amenities (such as national and state parks).

Understanding the assets available in rural areas will foster effective investment that can unleash the potential of these communities and their residents. More specifically, highlighting the assets present in rural communities can show private investors how directing capital to places with relevant assets can provide necessary infrastructure or produce a robust return on their investments.

A three-part strategy can promote effective economic development for rural communities:

- Pairing a data-driven approach to target investment efficiently with a community engagement approach so communities can determine their own paths to prosperity

- Building rural towns’ administrative capacities to facilitate the disbursement of funds and development of projects in their communities

- Creating a public-private partnership framework to foster investments from the private sector and philanthropy

Let’s now examine each part in turn, after which I will give two recent examples of these three strategies acting in tandem.

Pairing a data-driven approach with community engagement

The first part of the strategy starts with a data-driven approach that can help target the communities most in need of the resources that can facilitate either public or private investment. Several economic indicators, including persistent poverty and the seven components of the Distressed Communities Index, point to communities in need of resources. These indicators can be paired with data on any federal programs providing resources to these communities, such as basic water and wastewater infrastructure services and high-speed internet access, as well as economic development programs, such as clean energy investments and business technical assistance.

Some of the rural communities with persistent poverty may qualify for specific additional resources. But sometimes these communities do not get any resources, which means that federal resources are not getting to the places with the greatest need. To avoid this result and prioritize the communities most in need, policymakers and stakeholders can use these indicators to identify communities and the resources they need to facilitate investment.

Resources such as workforce development initiatives, basic infrastructure, and technical assistance for local businesses can shift the outlook and put them in a position to prosper. As discussed by Upjohn Institute economist Tim Bartik in his recent paper for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, one example is building business-specific infrastructure, such as high-tech research parks alongside industrial access roads that can facilitate the movement of supplies, workers, or output.34

Once communities are selected, engagement with the residents in these communities is vital so that they feel that policy development and execution is done “with them” and not “to them.” This is important so that residents can see that the federal government is centering their needs and honoring their lived experiences, rather than acting on behalf of economic elites alighting in their communities from elsewhere in the country.

Several federal agencies have regional and field offices where members of rural communities can work directly with agency officials to learn about available resources, point out the needs of their communities, and drive investments. Partnerships between federal and local officials can create a blueprint to drive investment and funding for projects in these communities.

Building administrative capacity in rural areas

The second part of the strategy recognizes that directing investment toward rural areas is not as simple as just sending money to these communities and their residents. A town must have the capacity to secure public investment, as well as receive and manage those resources. Many small towns do not have grant writers who know how to navigate 100-page federal applications or experts who can write feasibility studies. It also is difficult for private businesses and entrepreneurs to get loans or loan guarantees when they often live in a banking desert.35

Small towns in rural areas need a strategy to build their administrative capacities. It is therefore imperative to connect rural communities to institutions—whether federal, state, or local government entities or nongovernmental organizations—that have the resources to help these communities access investment dollars. Many large metropolitan areas have planning departments that guide cities when they apply for federal funding, for instance. Creating a similar structure supported by the federal government for small towns and rural areas would help foster investment and growth.

Fostering public-private partnerships

The third part of the strategy recognizes that it is not solely the role of the federal government to foster economic development in rural areas. The private and philanthropic sectors can play vital roles. Yet these groups often do not know where or in whom to invest. There is therefore a need to create a unique public-private platform that can connect these groups with projects in rural communities.

The first two parts of the strategy naturally lead into this third part, where collaboration between federal and local officials in determining the needs of their rural communities and developing projects for these communities can provide an avenue for the private and philanthropic sectors to bring their resources to bear.

This three-part strategy in action

Two federal programs launched by the Biden administration exemplify these three strategies in action together in rural America. One is the Recompete Pilot Program, with one telling initiative in eastern Kentucky. The other is the Rural Partners Network initiative, with a successful effort to highlight in Mississippi.

The Recompete Pilot Program

The Recompete Pilot Program is part of the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, with a special focus on rural places.36 One of its projects is the Eastern Kentucky Runway Recompete Plan, led by the nonprofit Shaping Our Appalachian Region, or SOAR. Eastern Kentucky is a rural region that has experienced significant job losses due to the demise of the local coal industry. The community is located in a region with persistent poverty but also has two large health care employers that could foster job growth.

SOAR was awarded $40 million in August 2024 to establish two new health care training facilities for well-paying jobs in nursing that will support the area’s health care centers. This project also will support a business incubator for regional firms that will provide physical space, technical assistance, and capital through a revolving loan fund.

This is a telling example of this strategy in practice—where a community was targeted through data identifying it as a distressed community with valuable assets and then working with the community through SOAR. The funding of this community-driven project by the federal government will promote economic development, leading to a revitalization of eastern Kentucky.

So far, this program continues to be funded under the second Trump administration, though with reduced staff.

Rural Partners Network initiative

The Biden administration employed another version of this strategy, with a goal of facilitating greater investment in rural communities, particularly those considered “left behind” as a result of persistent poverty. Called the Rural Partners Network, or RPN,37 this initiative recognized that the lack of capacity is one of the biggest obstacles for rural areas to access resources from both the public and private sectors.

The Rural Partners Network was a collaboration between the federal government and local civic organizations to build capacity in a select set of communities and provide technical assistance through an online resource that offered a one-stop shop for communities to learn about available federal resources. Dedicated federal RPN staff, known as community liaisons, worked with a community to identify projects where help was needed. These community liaisons worked with rural desk officers—staff from nearly 20 federal agencies with deep knowledge of agency programs—to identify the program or set of programs that best served those needs.

Though the RPN initiative has largely been shuttered by the Trump administration, it is a model for delivering resources to places that lack the capacity and ability to take advantage of federal resources. This model has the added benefit of helping the private sector and philanthropy direct their funding and expertise to rural communities. The Rural Partners Network, between fiscal years 2023 and 2024, was responsible for $1.3 billion in public investments over nearly 6,000 investments in 10 states and Puerto Rico and created nearly 4,000 new partnerships. This shows the potential for much more significant investments to flow into rural communities.

One example of the RPN initiative in action is in Mississippi, where community networks in the northwestern Delta region of the state developed a plan to install photovoltaic solar systems that would generate nearly 1 million kilowatts hours of electricity per year. Other projects in Mississippi include funding for deployment of fiber-to-the-premises network that will connect households, farms, businesses, and public schools. These types of infrastructure investments will provide a foundation for these communities to support future economic development.

Conclusion

The disinvestment in rural areas under the current administration provides an opportunity for policymakers in the U.S. Congress to tout a proven place-based approach to boosting economic growth. This essay outlines a three-pronged, place-based strategy for economic development that recognizes that assets exist in all rural communities and partners with the community in employing these assets to advance rural prosperity. This strategy has been employed through the Rural Partners Network initiative that has brought funding and local and national partners to underserved communities across the United States. The strategy was also employed in the CHIPS and Science Act through the Recompete Pilot Program that directed funding to rural places.

While this strategy has been rolled back under the Trump administration, the opportunity is there for future policymakers. To take advantage of it, policymakers must recognize the value and assets in rural places, which are primarily the communities’ people. Recognizing these assets will go a long way to revitalizing these communities and garnering the support that has lagged for decades.

About the author

Gbenga Ajilore is the chief economist at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Previously, he served as a senior advisor in the Office of the Undersecretary for Rural Development at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the Biden administration, and was a senior economist at the Center for American Progress and a tenured associate professor of economics at the University of Toledo.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

End Notes

1. Gbenga Ajilore and Caius Z. Willingham, “Redefining Rural America” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/redefining-rural-america/.

2. Cardiff Garcia and Stacey Vanek Smith, “Myths And Realities of America’s Rural Economy,” NPR, March 22, 2021, available at https://www.npr.org/2021/03/22/980064728/myths-and-realities-of-americas-rural-economy.

3. Center on Rural Innovation, “Who Lives in Rural America? How Data Shapes (and Misshapes) Conceptions of Diversity in Rural America,” CORI blog, January 12, 2023, available at https://ruralinnovation.us/blog/who-lives-in-rural-america-part-2/.

4. Austin Sanders, “Atlas of Rural and Small-Town America” (Washington: USDA Economic Research Service, 2025), available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/atlas-of-rural-and-small-town-america.

5. Austin Sanders, “County Typology Codes” (Washington: USDA Economic Research Service, 2025), available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes.

6. Sarah Melotte, “Rural America’s Post-Pandemic Job Recovery Varies by Industry and Region,” The Daily Yonder, June 19, 2024, available at https://dailyyonder.com/rural-americas-post-pandemic-job-recovery-varies-by-industry-and-region/2024/06/19/.

7. Center on Rural Innovation, “Community Stories,” available at https://ruralinnovation.us/community-impact/community-stories/ (last accessed August 2025).

8. Trevor E. Brown and Suzanne Mettler, “Sequential Polarization: The Development of the Rural-Urban Political Divide, 1976 – 2020,” Perspectives on Politics 22 (3) (2024), available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/sequential-polarization-the-development-of-the-ruralurban-historic-divide-19762020/ED2077E0263BC149FED8538CD9B27109.

9. Hannah Hartig and others, “Behind Trump’s 2024 Victory, a More Racially and Ethnically Diverse Voter Coalition” (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2025), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2025/06/26/voting-patterns-in-the-2024-election/.

10. Lisa Held, “Exclusive: DOGE Cancels Contract That Enables Farmer Payments, Despite $0 Savings,” Civil Eats blog, February 19, 2025, available at https://civileats.com/2025/02/19/exclusive-doge-cancels-contract-that-enables-farmer-payments-despite-0-savings/.

11. Joseph Clark, “Farmers Blindsided by Sudden Pivot from Major US Agency: ‘This Program Has Been Key to Helping People,” Yahoo! News, July 27, 2025, available at https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/farmers-blindsided-sudden-pivot-major-101527106.html?guccounter=1.

12. U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Secretary Rollins Announces USDA Reorganization, Restoring the Department’s Core Mission of Supporting American Agriculture,” Press release, July 24, 2025, available at https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2025/07/24/secretary-rollins-announces-usda-reorganization-restoring-departments-core-mission-supporting.

13. Daniella Ignacio, “Trump Wants to Move Federal Jobs Out of the DC Area. Here’s What It Was Like the Last Time He Did That,” Washingtonian, November 25, 2024, available at https://www.washingtonian.com/2024/11/25/trump-wants-to-move-federal-jobs-out-of-the-dc-area-heres-what-it-was-like-the-last-time-he-did-that/.

14. Center on Rural Innovation, “Defining rural America: The consequences of how we count,” CORI blog, July 20, 2022, available at https://ruralinnovation.us/blog/defining-rural-america/.

15. Tracy Farrigan, “Rural Poverty & Well-Being” (Washington: USDA Economic Research Service, 2025), available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-poverty-well-being.

16. Economic Innovation Group, “Distressed Communities Index (DCI),” available at https://eig.org/distressed-communities/?geo=states&lat=38.01&lon=-96.42&z=4.32 (last accessed August 2025).

17. Fabian Eckert, John Juneau, and Michael Peters, “Sprouting Cities: How Rural America Industrialized,” AEA Papers and Proceedings 113 (2023), available at https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pandp.20231075.

18. James C. Cobb, The Selling of the South (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

19. Gbenga Ajilore and Caius Z. Willingham, “The Modern Company Town” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/modern-company-town/.

20. Justin Wiltshire, “Walmart is a Monopsonist that Depresses Earnings and Employment Beyond its Own Walls, but U.S. Policymakers Can Do Something About It” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/walmart-is-a-monopsonist-that-depresses-earnings-and-employment-beyond-its-own-walls-but-u-s-policymakers-can-do-something-about-it/.

21. Leslie Whitener and David McGranahan, “Rural America: Opportunities and Challenges,” Amber Waves, February 3, 2003, available at https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2003/february/rural-america.

22. Amanda Weinstein and Adam Dewbury, “Rural America’s Struggle to Access Private Capital” (Hartland, VT: Center on Rural Innovation, 2025), available at https://ruralinnovation.us/resources/reports/rural-americas-struggle-to-access-private-capital/

23. Ben Gose, “Rural America Is Struggling. Where’s Philanthropy?” The Chronicle of Philanthropy, September 10, 2024, available at https://www.philanthropy.com/article/rural-america-is-struggling-wheres-philanthropy.

24. National Performance Review, “A Brief History of the National Performance Review” (1997), available at https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/npr/library/papers/bkgrd/brief.html.

25. August Benzow, “The Economic and Political Dynamics of Rural America” (Washington: Economic Innovation Group, 2025), available at https://eig.org/rural-america/.

26. Tarun Ramesh and Emily Gee, “Rural Hospital Closures Reduce Access to Emergency Care” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/article/rural-hospital-closures-reduce-access-emergency-care/.

27. Jeffrey Brown, “How schools are forced to close as rural populations dwindle,” PBS News Hour, November 27, 2018, available at https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-schools-are-forced-to-close-as-rural-populations-dwindle.

28. Sirus H. Dehdari, “Understanding the Role of Immigration and Economic Factors in Boosting Support for Far-Right Political Parties” (Washington: Washington Center for Economic Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/understanding-the-role-of-immigration-and-economic-factors-in-boosting-support-for-far-right-political-parties/.

29. Kennedy O’ Dell, “Redefining Rural: What Rural Prosperity and the Geography of Newly Affluent Rural Communities Tells Us About Rural Development” (Washington: Economic Innovation Group, 2021), available at https://eig.org/redefining-rural-what-rural-prosperity-and-the-geography-of-newly-affluent-rural-communities-tells-us-about-rural-development/.

30. Ali Abboud and Michael R. Betz, “The Local Economic Impacts of the Oil and Gas Industry: Boom, Bust and Resilience to Shocks,” Energy Economics 99 (2021), available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988321001900.

31. Sarah Melotte, “Rural Population Grows for Second Consecutive Year,” The Daily Yonder, April 2, 2024, https://dailyyonder.com/rural-population-grows-for-second-consecutive-year/2024/04/02/.

32. Lionel J. Beaulieu, “Promoting Community Vitality & Sustainability, The Community Capitals Framework” (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue Center for Regional Development, 2014), available at https://cdextlibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/resource-media/2020/12/Community-Capitals-Beaulieu.pdf.

33. Corianne Payton Scally and others, “Reenvisioning Rural America: How to Invest in the Strengths and Potential of Rural Communities” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2021), available at https://reenvisioning-rural-america.urban.org/.

34. Tim Bartik, “Federal and State Governments Can Help Solve the Employment Problems of People in Distressed Places to Spur Equitable Growth” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/federal-and-state-governments-can-help-solve-the-employment-problems-of-people-in-distressed-places-to-spur-equitable-growth/.

35. Lali Shaffer, “Who Are the 12 Million People Living in Banking Deserts,” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta blog, May 13, 2024, available at https://www.atlantafed.org/blogs/take-on-payments/2024/05/13/who-are-the-12-million-people-living-in-banking-deserts.

36. Scott Andes and Sathiyan Sivakumaran, “How the Recompete Pilot Program Meets the Unique Needs of Rural American Communities” (Washington: U.S. Economic Development Administration, 2024), available at https://www.eda.gov/news/blog/2024/08/09/how-recompete-pilot-program-meets-unique-needs-rural-american-communities.

37. “Rural Partners Network,” available at https://www.rural.gov/ (last accessed August 2025).

Stay updated on our latest research