Ahead of new U.S. jobs data releases, here’s what employment growth and job switching mean for wage disparities in the U.S. labor market

Overview

Later this week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release data on February 2023 job growth through its Employment Situation Summary. It will also release information on job openings, hires, and separations during the month of January 2023 through its Job Openings and Labor Turnover survey. As new economic data are published and the U.S. labor market continues to recover from the COVID-19 recession, one important underlying dynamic that economists and policymakers alike need to heed is the relationship between employment growth, job switching, and wage disparities in the U.S. labor market.

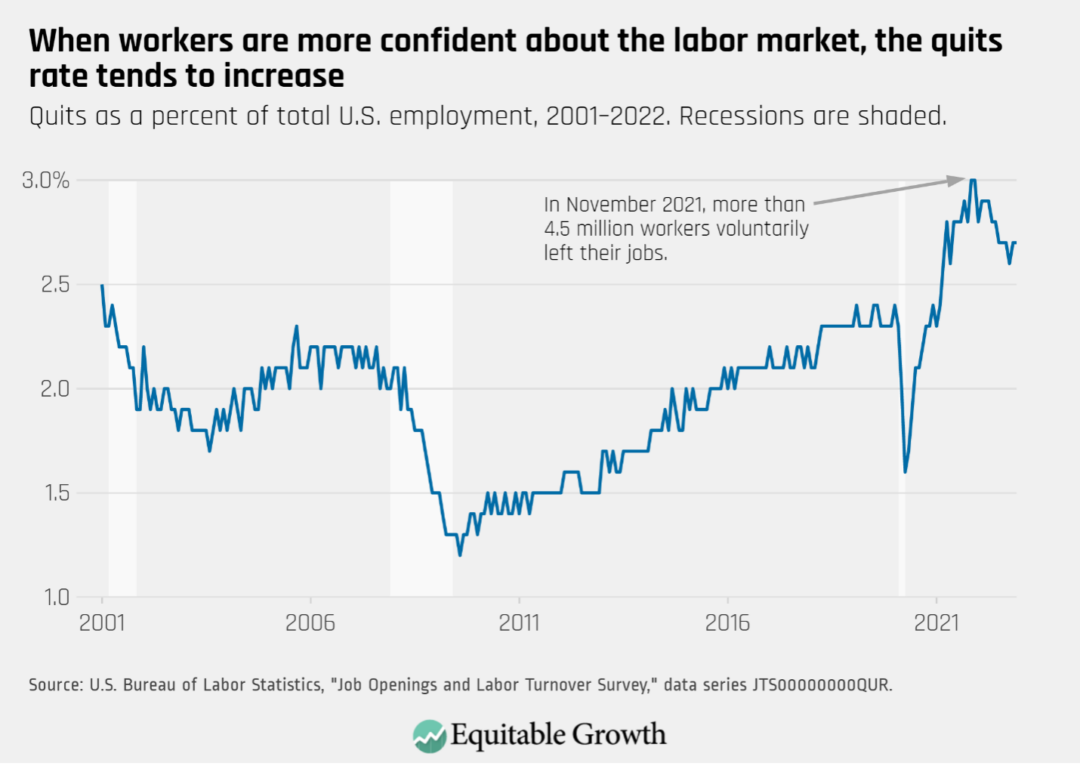

Topline economic indicators show that the U.S. labor market is remarkably strong. Over the past 3 months, the U.S. economy added an average of 356,000 jobs. The national joblessness rate, at 3.4 percent, is currently at a 50-year low. Almost all major industries have surpassed their pre-pandemic employment levels. And the quits rate continues to be near record highs—a sign that U.S. workers are confident in the labor market and in finding new and better employment opportunities.

Underlying these strong positive trends are several key developments that are shaping the recovery from the short but deep COVID-19 recession of 2020. One is the real wage gains experienced by workers at the bottom of the wage distribution. Another is the high rates of quits among these workers and U.S. workers overall. And a third development is the positive relationship between these two dynamics.

This issue brief will detail these three trends to put into perspective the importance of the stronger bargaining power experienced by low-wage workers in the wake of the most recent recession, as well as the key social infrastructure investments and policies that need to be undertaken in order to maintain and strengthen the gains workers made over the first 2.5 years of the economic recovery.

The topline U.S. labor market indicators

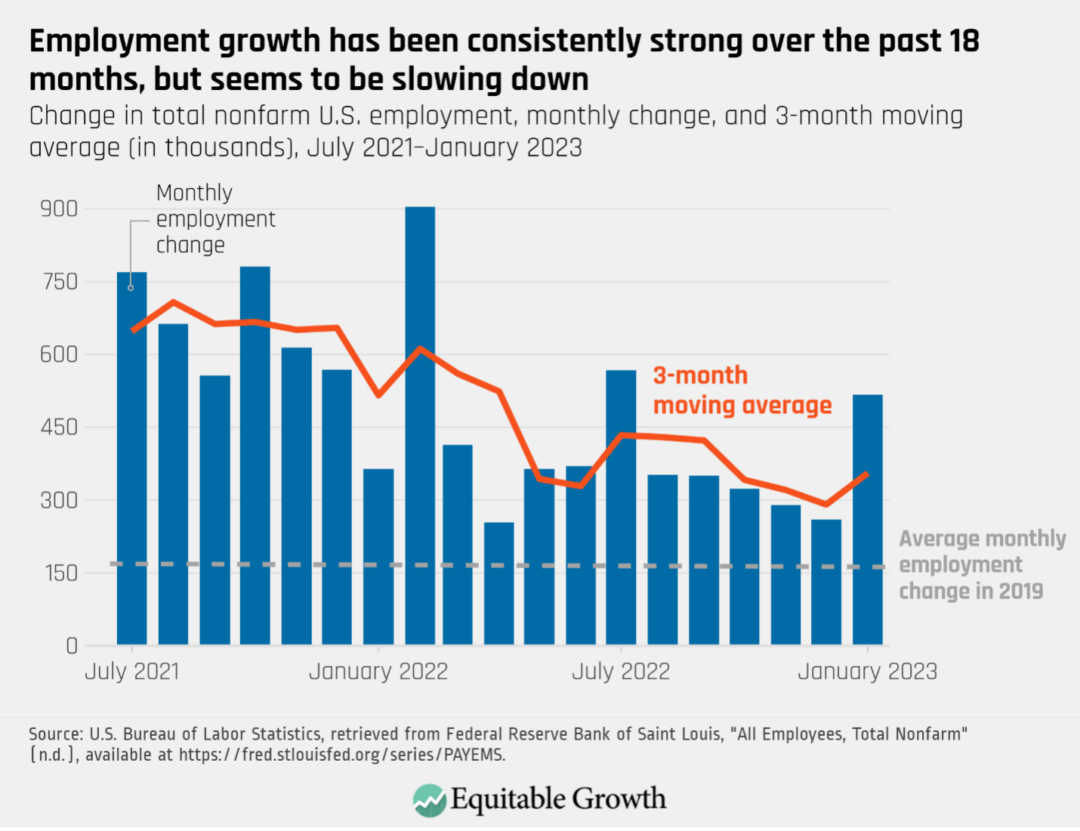

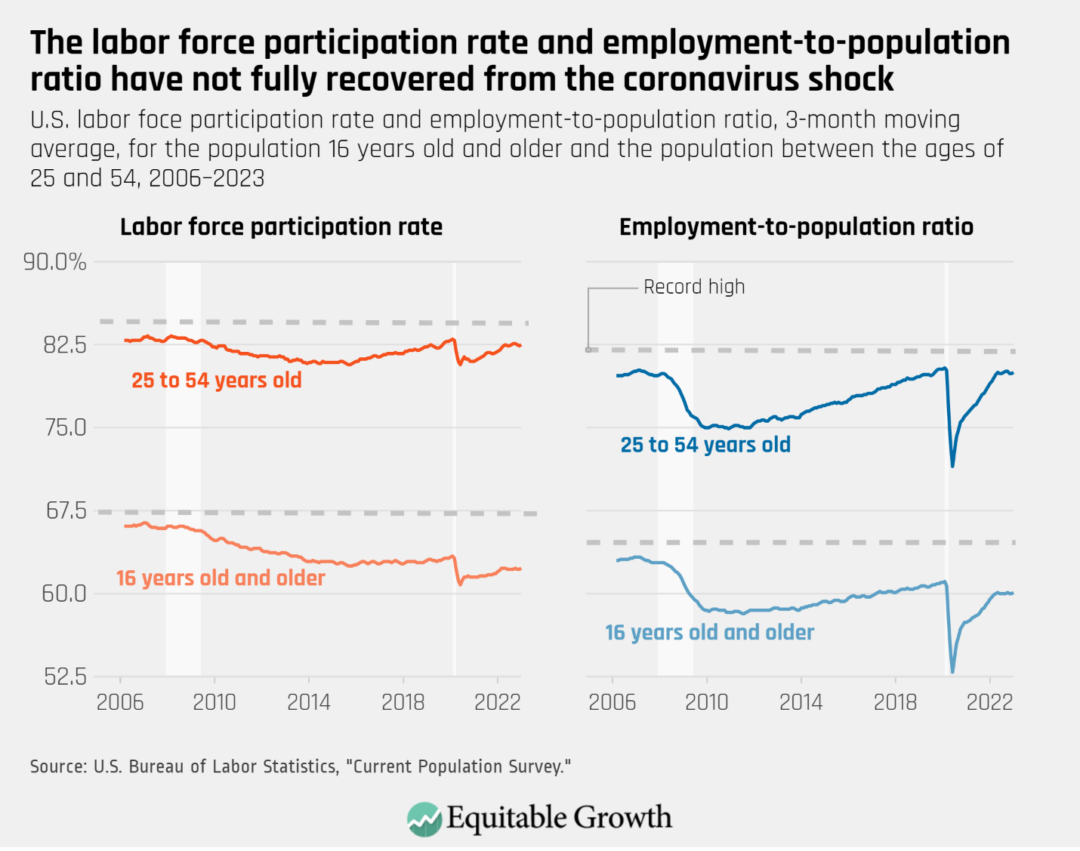

Let’s first set the stage by examining three important U.S. labor market indicators: employment growth, the labor force participation rate, and the prime-age employment-to-population ratio, or the share of 25- to 54-year-olds who are employed. Employment growth is strong but may be slowing down. And while neither the labor force participation rate nor the prime-age employment-to-population ratio is back to its February 2020 levels, both metrics experienced upticks in 2022. (See Figures 1 and 2.)

Figure 1

Figure 2

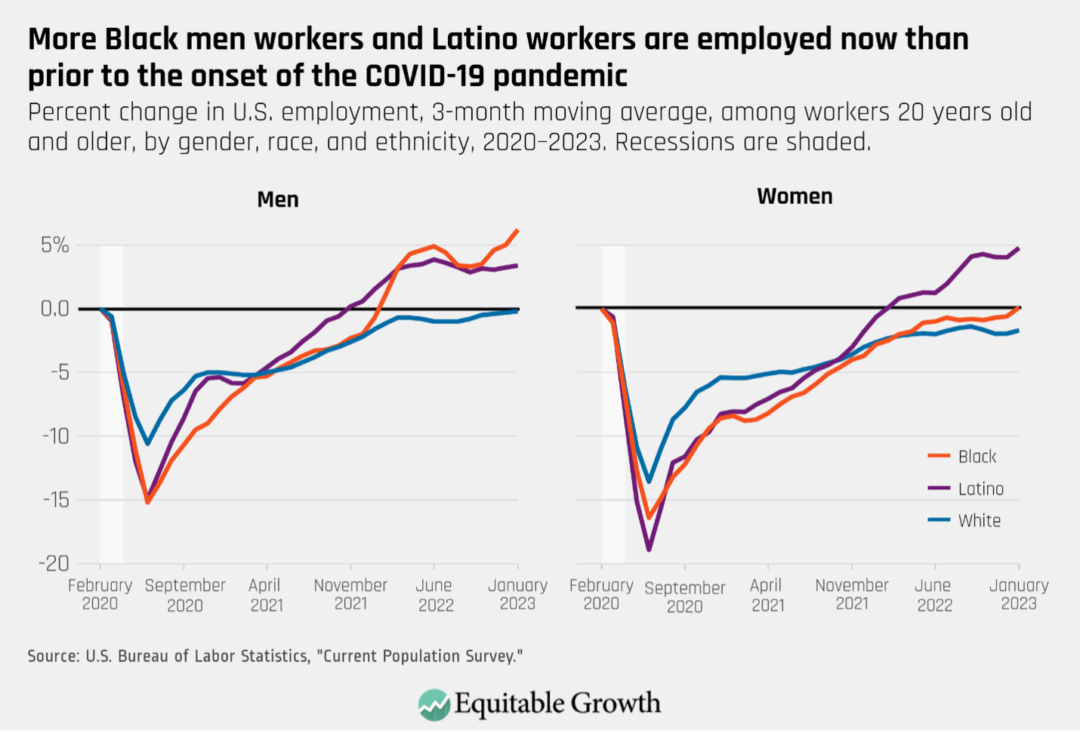

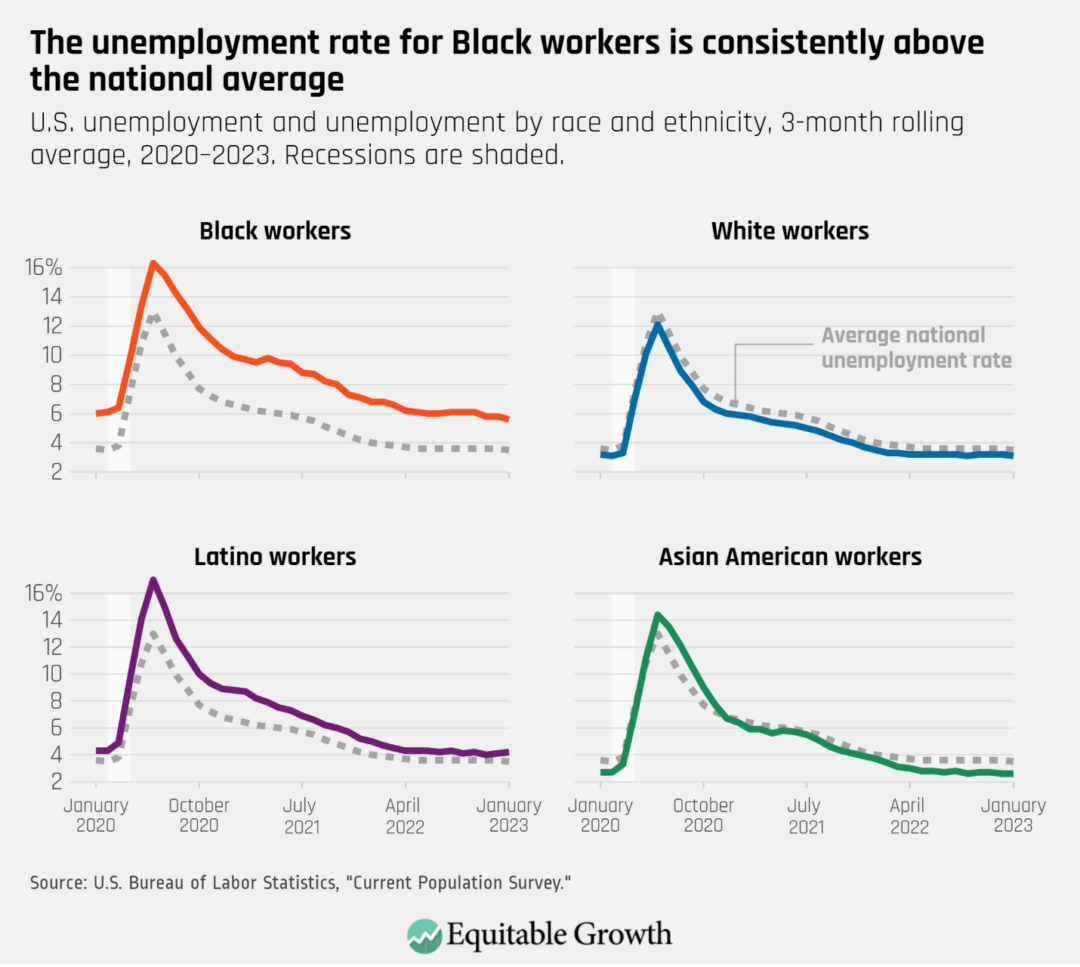

Employment outcomes continue to be widely unequal across demographic groups, but the hot U.S. labor market seems to be narrowing some of the longstanding disparities that then skyrocketed during the onset of the pandemic in early 2020. The unemployment rate for workers without a high school diploma, for instance, is at a record low, and employment among Black men and Latino workers, both men and women, has experienced a particularly strong bounce back.

Indeed, the number of Black men who are employed was almost 8 percent greater in January 2023 than it was during February 2020, reflecting stronger job growth than for any other group of workers. Likewise, the gap between the national joblessness rate and the joblessness rate of both Black workers and Latino workers is smaller now than during the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 recession in the early spring of 2020. (See Figures 3 and 4.)

Figure 3

Figure 4

A higher quits rate is associated with greater worker bargaining power

Why are some U.S. labor market disparities narrowing? The year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of U.S. workers quitting their jobs rose to record highs. Some workers left their jobs because they no longer felt safe at work; others moved. And other workers had new or greater caregiving responsibilities, started their own businesses, or decided to pursue another career path. Indeed, many workers not only switched employers but also decided to transition to another industry or occupation altogether.

During the final 2 months of 2021, the monthly national quits rate—or the share of all workers who voluntarily leave their job in a given month—reached a record peak of 3 percent. More than 4.5 million workers quit in November 2021—the highest number since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics started reporting the metric in the early 2000s. While both the quits rate and the absolute number of quits declined throughout the course of 2022, these two statistics continue to be well above their pre-pandemic levels. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

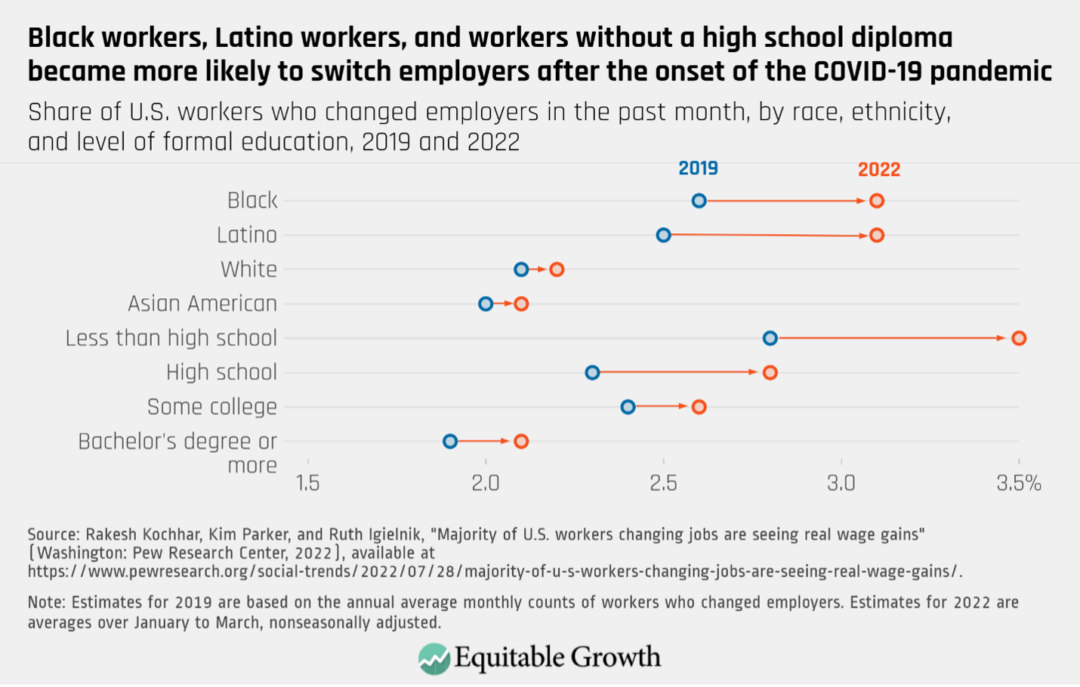

As quits and job mobility accelerated in the years after the initial shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, the pace at which workers changed jobs increased more for some demographic groups than others. An analysis by the Pew Research Center, for example, finds that the share of Black workers and Latino workers who change employers in a given month is substantially higher than the share of Asian American workers and White workers who make that same switch.

Moreover, the same analysis finds that while Asian American workers and White workers were about as likely to change employers in 2019 as in 2022, the likelihood that Black workers and Latino workers moved from one employer to another increased substantially after the onset of the pandemic. Workers with a high school diploma or less were also much more likely to switch employers in 2022 than in 2019. (See Figure 6.)

Figure 6

Workers of color and workers with lower levels of formal education change employers especially often because they are more likely to be sorted into lower-quality jobs. Indeed, inadequate pay, insufficient benefits, lack of opportunities for career advancement, unsafe working conditions, and undesirable working environments are some of the main drivers behind the particularly high turnover rates in low-paying industries such as retail and leisure and hospitality.

At the same time, a higher quits rate and greater opportunities for job mobility seem to be leading to better employment outcomes for many U.S. workers. People are more likely to leave their current jobs when the labor market is strong, and they are confident that they will find employment opportunities elsewhere. Indeed, research shows that the great majority of workers who quit move on directly to another job, rather than spending time unemployed or stepping out of the labor force altogether. In economic speak, then, a higher quits rate tends to reflect that workers have more outside options.

A climbing quits rate also is associated with faster wage growth because workers tend to transition to higher-paying opportunities after voluntarily leaving their previous jobs. And, as a higher share of the workforce quits, employers usually have to offer higher wages in order to attract and retain employees, shifting bargaining power toward labor. Indeed, several studies suggest that the sluggish earnings growth that U.S. workers experienced during most of the recovery from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 can be, at least in part, attributed to a decline in what economists call job-to-job transitions.

In addition, economic disparities can be reduced amid a tight labor market due precisely to a higher number of job openings and an elevated quits rate. Job switchers usually experience stronger wage growth than job stayers, especially during economic booms, and research shows that lower-wage workers tend to rely more on job switching to get increases in pay than higher-wage workers.

In a 2021 study, for instance, a team of economists used administrative data on dual job-holders to examine the pathways workers use to get higher wages. Their findings suggest that the highest earners were much more likely to see increases in pay by bargaining with their employers, since firms generally have to spend more time and resources filling higher-wage positions and are therefore more likely to make efforts to retain higher-paid employees. Those in the bottom of the distribution, in contrast, usually had to change firms in order to get a raise.

Similarly, research by Nathan Wilmers and William Kimball at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology finds that workers in low-wage occupations are much more likely to move on to higher-quality jobs when switching employers than when changing positions through internal hiring processes.

The tight labor market reduced wage inequality in the U.S. economy, but there are signs that disparities are no longer narrowing

The rapid recovery of the U.S. labor market after the COVID-19 recession in 2020 was accompanied by faster nominal wage growth for U.S. workers, especially for those in low-wage jobs. An analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics finds, for instance, that between December 2019 and December 2021, wage growth was fastest in the industries of retail trade and leisure and hospitality—the lowest-paid sectors of the U.S. economy. And an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute finds that in the same year, workers in the bottom 30 percent of the wage distribution were the only ones to experience real wage gains. That is, these workers saw a wage increase even after accounting for inflation.

Greater competition for workers, recent research shows, was an important driver of this compression in wages. For instance, a study by David Autor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Annie McGrew and Arindrajit Dube at the University of Massachusetts Amherst finds that as the U.S. labor market started to recover from the initial COVID-19 shock, increased competition for labor led to particularly strong wage growth among the lowest-paid workers, who now had greater access to better-paying employers.

Specifically, the team of economists analyzed differences in state-level unemployment rates and job switching rates—two metrics researchers use to determine how tight a given labor market is. They find that in states with lower joblessness and relatively more job-to-job transitions, real wage growth among low-wage workers was faster, especially among younger workers without a college degree. In addition, Autor, McGrew, and Dube find that as the lowest-paid workers became especially likely to quit their previous job in response to higher-paying opportunities elsewhere.

Overall, these dynamics contributed to an important decline in the wage divide, reversing about 25 percent of the four-decade increase in the gap between workers in the top 10 percent of the wage distribution and workers in the bottom 10 percent.

But these recent U.S. labor market dynamics, which triggered what Autor, McGrew, and Dube call the “great compression” in wages, might be decelerating. In the second half of 2022, wage growth slowed down for workers in general, and for workers in low-paying sectors such as leisure and hospitality in particular. And while employment growth continues to be strong and the quits rate is still relatively high, there are signs that employers’ competition for workers has cooled over the past few months.

Conclusion

When the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics later this week releases its February 2023 data on job growth and information on job openings, hires, and separations during the month of January 2023, these recent underlying trends in the U.S. labor market will become a bit more clear.

As the new data come in, policymakers need to consider how to institutionalize worker power and enact policies that proactively and intentionally promote broadly shared growth, so that wage disparities continue to narrow. A higher federal minimum wage, providing government agencies with the tools and resources to better enforce labor standards, and making it easier for workers to form and join unions, for example, would all go a long way to foster better outcomes for U.S. workers in the bottom of the wage distribution, even when the U.S. labor market is not sizzling hot.