May jobs report: Young workers are entering a uniquely evolving U.S. labor market

The recovery in the U.S. labor market continued in May, with 390,000 jobs added and the unemployment rate holding steady at nearly its pre-pandemic level at 3.6 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Employment Situation Summary released today. After 12 consecutive months of adding more than 400,000 jobs per month, that level decreased slightly last month, but continues to be above the pace of job growth pre-pandemic. And while earnings growth has averaged 5.2 percent over the past year, the annualized 3-month moving average for March to May was 4.5 percent compared to 4.8 percent for the prior three months.

In short, the jobs recovery amid the economic impact of the pandemic has been remarkable, but gains have been uneven and it is unclear whether continued fast-paced gains will continue.

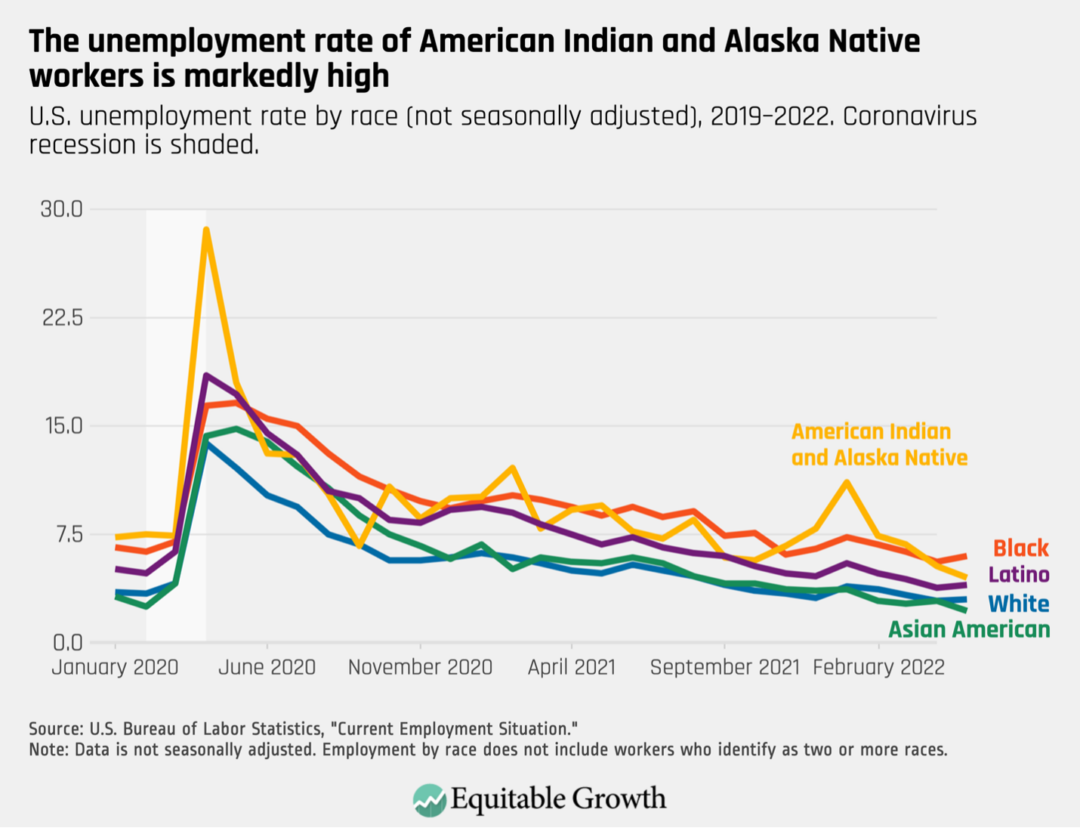

A slowing pace of recovery could also mean that the persistent disparities experienced by workers who face historical barriers to opportunity will likely be more difficult to overcome without the tailwind of a tight labor market. The non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for Black workers, at 3.0 percent, is nearly twice that of White workers, at 6.0 percent. American Indian and Alaska Native workers are facing an unemployment rate of 4.5 percent while Latino workers, who were among the hardest hit in the pandemic, are facing an unemployment rate of 4.0 percent. (The Bureau of Labor Statistics began publishing monthly data on American Indian and Alaska Native workers in February 2022, but does not report that data on a seasonally adjusted basis.)

The unemployment rate for Asian American workers is lower than the rate for White workers, at 2.2 percent. But our analysis of the April jobs report noted that Asian American workers experience significantly elevated levels of long-term unemployment compared to other workers.

Each of these realities demonstrate how market forces alone are not sufficient to resolve long-standing labor market inequalities. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

The jobs market today for young workers presents its own unique challenges and opportunities. With end of the school year, and with high school and college graduations now in train, many young workers are entering the job market at an unprecedented time.

The unemployment rate of workers ages 16 to 19 was 10.4 percent in May, up from 9.6 percent one year prior, but remarkably low compared to the historical average. The most recent Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey from April released earlier this week found that there are 11.4 million job openings, a slight decrease from one month prior but above historical averages. As young workers may be finishing their school years, these conditions could have long-lasting impacts on their economic security.

Recession scarring for younger workers

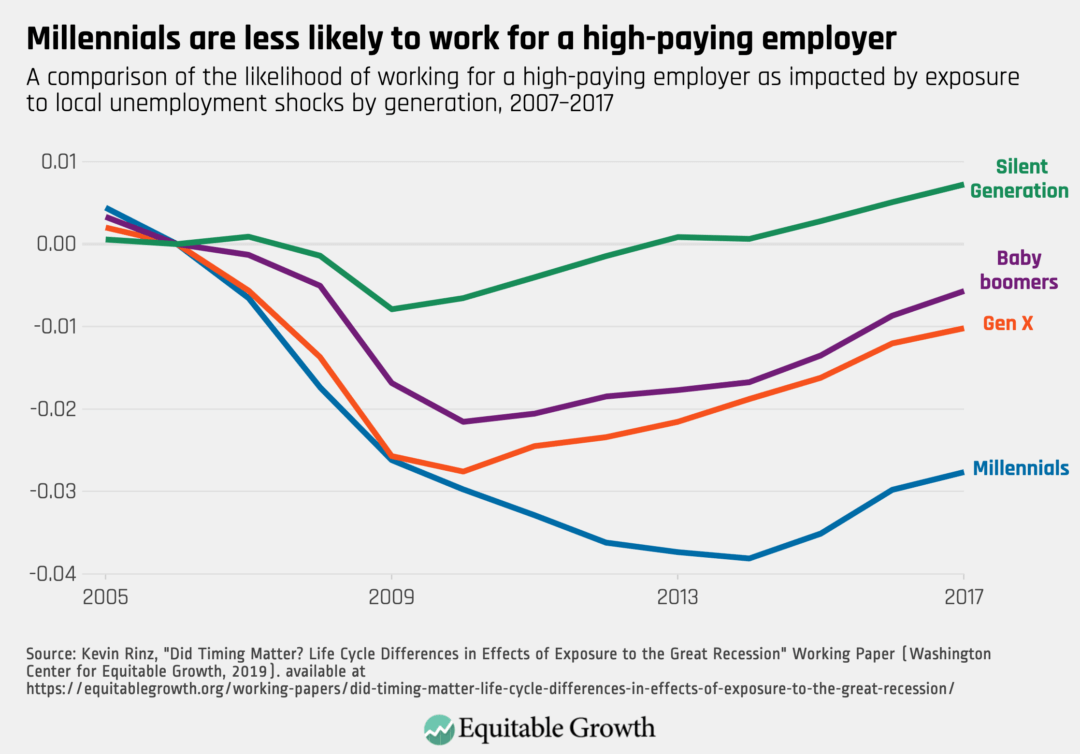

A body of economics research finds that entering the U.S. labor market during a recession has impacts on young workers that can last long after the recession has abated. The long-run effects of an economic shock is known in economics as “hysteresis,” which describes negative effects that persist past the event causing the shock. Research by Kevin Rinz of the U.S. Census Bureau found that during the Great Recession of 2007–2009, younger workers recovered their levels of employment more quickly than other generations, but they faced both large and persistent earnings losses for up to 10 years following the initial shock.

Workers cannot choose when they were born, but the precise timing of their initial entry into the labor market has long-term impacts. Jesse Rothstein of University of California, Berkeley, finds that college graduates who entered the labor market during the end of the Great Recession in 2009 through the initial tepid recovery into 2011 had lower employment and earnings by 2017 compared to college graduates who entered the labor market immediately prior to the recession or post-2012.

What’s more, hysteresis is an enduring historical problem for young workers. Hannes Schwandt of Northwestern University and Till von Wachter of the University of California, Los Angeles, find that these “unlucky-cohorts” effects were common across business cycles in the modern U.S. labor market from 1976 to 2015, and particularly scarring for workers who face other disadvantages, such as non-white workers and those without a high school degree.

One of the critical factors in shaping these scars of recessions is where re-employment occurs. Rinz finds that younger workers are more likely to work for lower-paying employers following initial local unemployment shocks. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Examined in a different way, Christopher Huckfeldt of Cornell University finds that increased hiring selectivity in recessions leads a situation in which it may be the optimal choice for a worker to switch into a lower-paying occupation when there are few other better alternatives. Workers who switch into lower paying occupations during a recession face earnings losses for a decade after the economic shock compared to workers who are also displaced in their jobs but stay in their occupation, the latter of whom recover their earnings within four years of an economic shock.

Then there’s the unique occupational impact of the coronavirus pandemic. It led to a sharp decline in in-person services followed by high labor demand now, and may shape the impact of this unique recession on the outcomes of younger workers.

Differences between the coronavirus recession, the Great Recession, and their aftermaths

As research relating to the Great Recession shows, the U.S. labor market for young people entering it as they begin their career can have long-term effects on their wages and career trajectory. Yet the labor market shocks and the pattern of recovery during the coronavirus recession and the subsequent economic recovery have diverged from those of the Great Recession in key ways that have implications for policy responses.

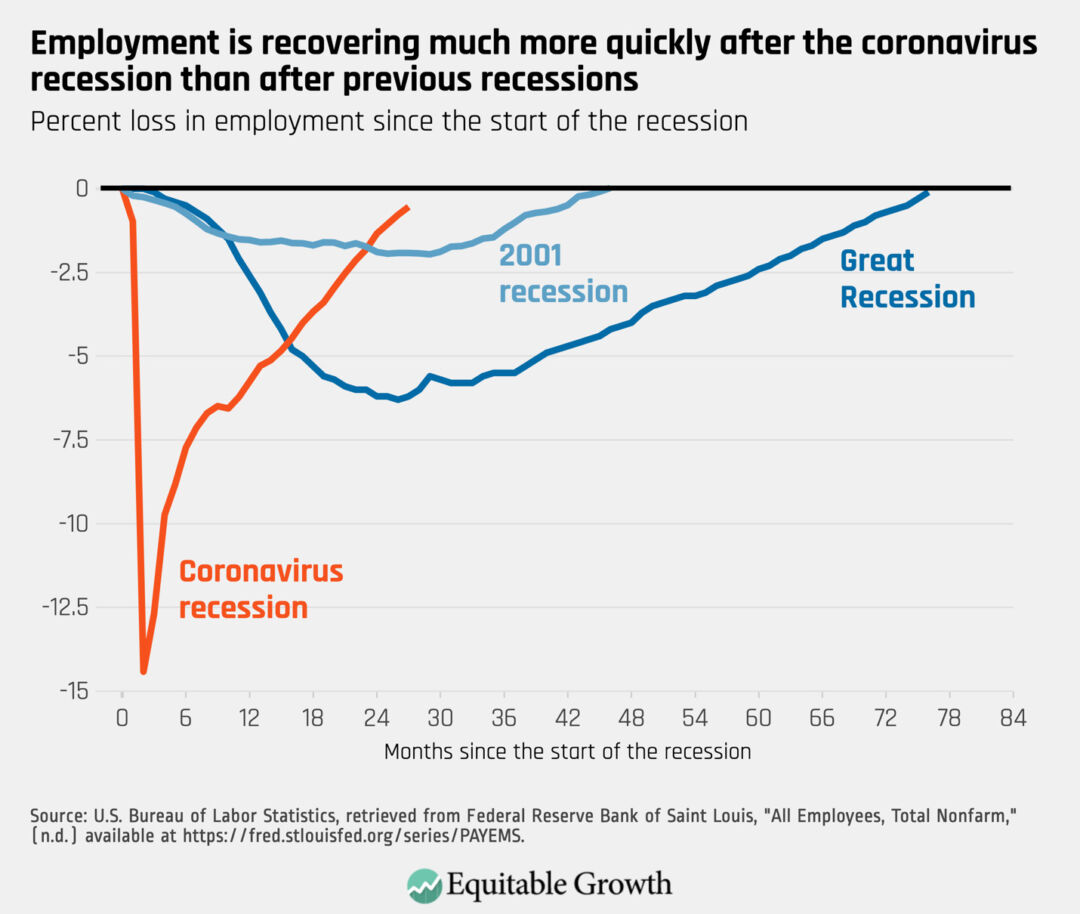

Employment losses in early and mid-2020 were both severe and unequal, disproportionately harming lower-income households and workers of color, especially those in hard-hit industries. The coronavirus pandemic’s early employment losses were also much greater than those of the Great Recession due to the sudden nature of emergency public health measures, and the fact that in-person services, particularly in leisure and hospitality, were most affected, as opposed to primarily the banking or housing sectors in the initial shock of the Great Recession.

Furthermore, the rate of recovery after the most recent recession has been much more rapid than after other recent recessions. Employment is nearing pre-pandemic levels just over two years after the initial shock compared to eight years after the Great Recession. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

The pandemic’s shocks to the economy and related public health measures also appear to have had mixed impacts on young people’s educational outcomes and their decisions about seeking higher education, both of which affect tightness in the labor market. Basically, young people decide how the mix of immediate employment and education opportunities alongside calculations about how the long-term prospects of investing in higher education would shape their human capital accumulation as well as their debt loads.

Indeed, students finishing high school in 2020 may have been more likely to graduate, according to a new analysis by The Brookings Institution, as “high school graduation rates actually increased for students with disabilities, English-language learners, and Black students.” But the Brookings analysis also explains that college entry and enrollment appears to have declined, as pandemic upheaval intersects with years of rising college costs.

The acute employment losses during the coronavirus recession were most severe in many industries that disproportionately employ young people, an analysis from the Economic Policy Institute found, with the unemployment rate for young workers ages 16 to 24 rising to 24.4 percent in spring 2020, more than twice the rate of workers 25 and older. An analysis from the Pew Research Center shows that young people who graduated college in 2020 were also less likely to enter the labor force that year, with labor force participation for recent college graduates ages 20 to 29 falling from 86 percent in 2019 to 79 percent in 2020. Data from the jobs website Indeed also suggest students and early-career workers would have been less likely to have in-person internships in 2020.

While these employment shocks for younger workers were severe, they have also been relatively short as the U.S. economy recovers. This is most striking when looking at labor market activity for the very youngest workers. The Drexel University Center for Labor Markets and Policy predicts that summer employment for 16- to 19-year olds will reach levels not seen since 2007, the summer before the start of the Great Recession. The high demand for workers right now also is strengthening wages for workers in industries that do not typically require college degrees, highlighting how workers’ bargaining power and other factors contribute the wage distribution beyond the “college wage premium.”

Policy responses to support younger workers in the U.S. labor market

The likely long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic on young workers’ outcomes remain unclear. The sudden and deep shocks of 2020 may have greater long-term effects for young workers entering the job market or making decisions about higher education that year, but the faster recovery may offset those harms to some extent. This suggests the need for policy interventions that both address the immediate harms for the most vulnerable young workers and strengthen our systems to be prepared for future shocks.

The experience of the first two years of the pandemic demonstrate how income supports and a stronger social infrastructure provide stability for weathering economic upheavals that reduce long-term negative consequences. Yet there are still gaps in the current system. For instance, as the Economic Policy Institute notes, expanded Unemployment Insurance benefits were not available to young people who were unable to enter the workforce. Policymakers should reform Unemployment Insurance and invest in building the administrative infrastructure for promising related programs, such as Short-Time Compensation, to protect vulnerable workers from sudden economic upheavals and mitigate the effects on their careers and on their households’ economic security.

Furthermore, developing a proposed job seekers allowance separate from the Unemployment Insurance system would help those who would remain ineligible for UI benefits as they initially enter the labor force following graduation.

As young workers drive unionization efforts across the country, policymakers also should strengthen workers’ bargaining power and worker protections, which research shows are especially crucial for improving earnings and reducing inequality for young workers without college degrees. At the same time, policymakers should make college more affordable and accessible for those who pursue higher education.

Canceling student loan debt also would provide much-needed relief to students and young workers as they navigate a changing labor market, and make them and their households more resilient down the road. Rebalancing economic power toward workers and young people would provide a foundation for future broadly shared growth.