Worker power and pay quality for young workers without a college degree in the United States

New cross-country research by economist David Howell at The New School (also an Equitable Growth grantee and a member of Equitable Growth’s Research Advisory Board) provides strong evidence that the patterns of low pay and persistent inequality for workers in the United States are the result of weak U.S. labor institutions and decades of policy choices. This research analyzes variations in pay quality for workers across several countries with similar market forces in recent decades, including an analysis of pay quality (see sidebar) for young workers ages 18–34 who do not have a college degree since 2000.

Some economists argue that the poor earnings outcomes for non-college-educated workers in the United States are due to a so-called skills gap or market forces that reward higher education due to skill-biased technical change. In contrast, Howell’s analysis shows that not only are outcomes for these workers markedly better in some countries than others—despite facing similar technological and market forces—but also that differences in pay quality are closely connected to the relative strength of labor institutions and worker power in those countries.

Young workers without a college degree in the United States have ‘exceptionally’ poor wage outcomes

In the first of two recent working papers, “How Exceptional is American Job Quality? The Incidence of Decent- and Poverty-Pay Jobs in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and France,” Howell looks at how earnings quality in the United States compares to that of other rich countries, focusing on the four mentioned in the title. His analysis finds that the United States has consistently worse patterns of pay quality and pay stagnation for workers in the bottom half of the pay distribution, compared to other rich countries, especially for young workers with lower levels of education.

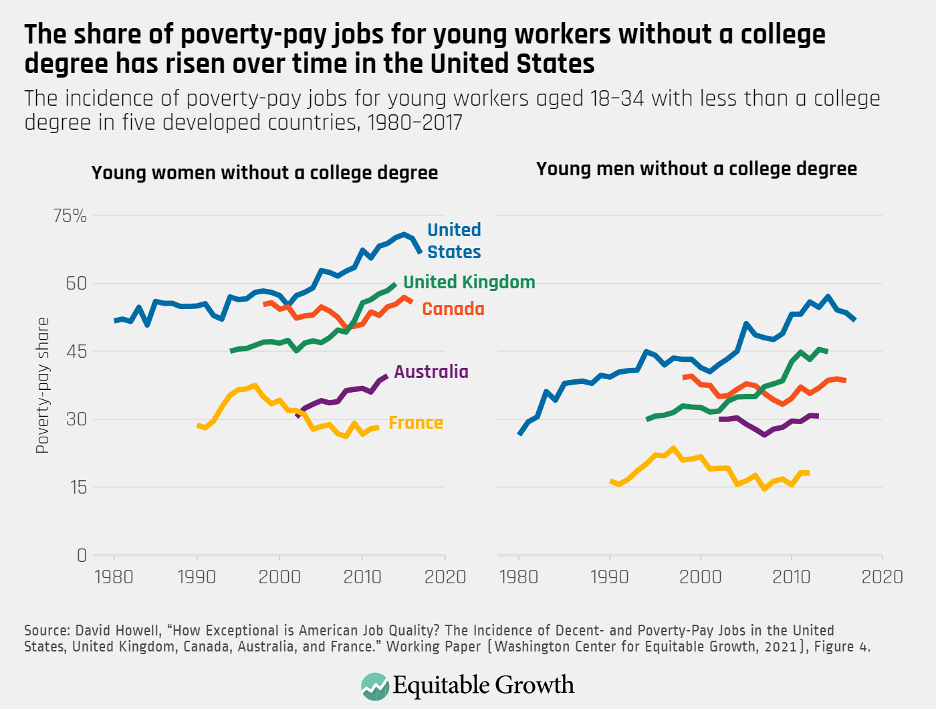

More than half of young workers ages 18 to 34 without a college degree in the United States earn poverty-level pay, with 70 percent of young women without degrees and 57 percent of young men working poverty-pay jobs. This level is markedly higher than it is in other, similar European countries and is only a fraction of that level in France—28 percent for young women without degrees and just 18 percent for young men without degrees. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

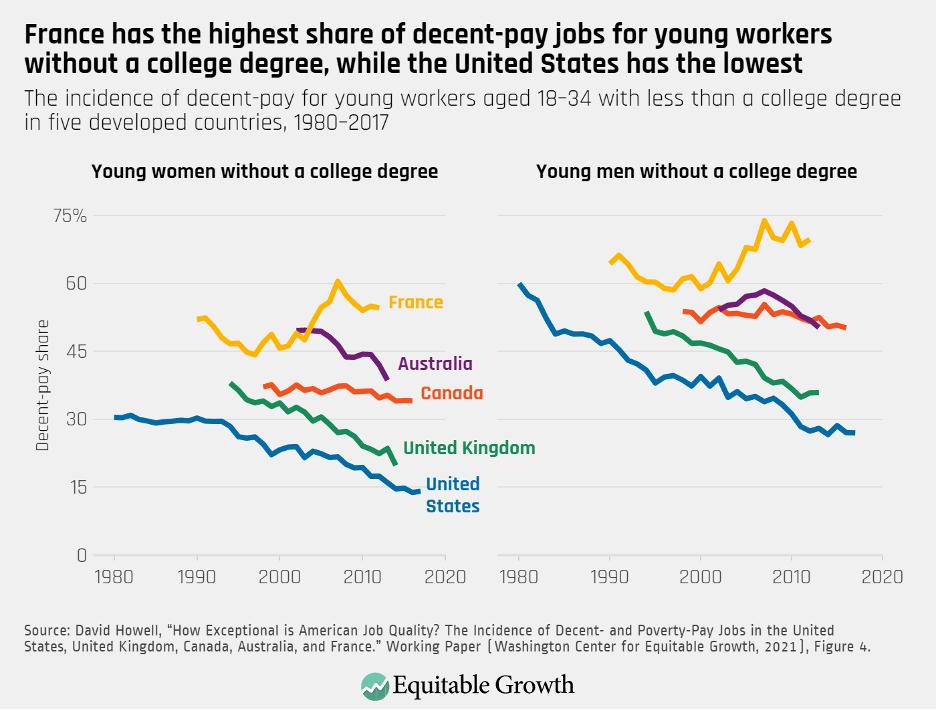

Looking at decent-pay jobs instead of poverty-pay jobs, the reverse is also clear. France consistently has a higher incidence of decent-pay jobs among young workers without college degrees, for both men and women, while the United States has the lowest incidence. The decent-pay gap between young, non-college-educated women in France and the United States rose from 22 percentage points in 1990 to more than 37 percentage points in 2012, and likewise rose for young, non-college-educated men in the same time period, from 17 percentage points to more than 42 percentage points.

Howell also shows that improving pay quality does not come at the cost of more inefficient labor markets. In other words, he demonstrates that the United States does not “make up” for its poor pay quality for non-college-educated workers with higher employment rates for that group. While specific outcomes vary for each country, the evidence does not show a clear or consistent link between countries’ employment levels and bottom-end pay distributions. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Furthermore, workers in countries with higher pay quality in the bottom half of the pay distribution do not face higher tax levels overall. In fact, Howell writes, “[t]he tax burden on American low-wage workers (21.5%) was, next to France, the highest—well above Canada (18.7%) and the U.K. (19.1%).”

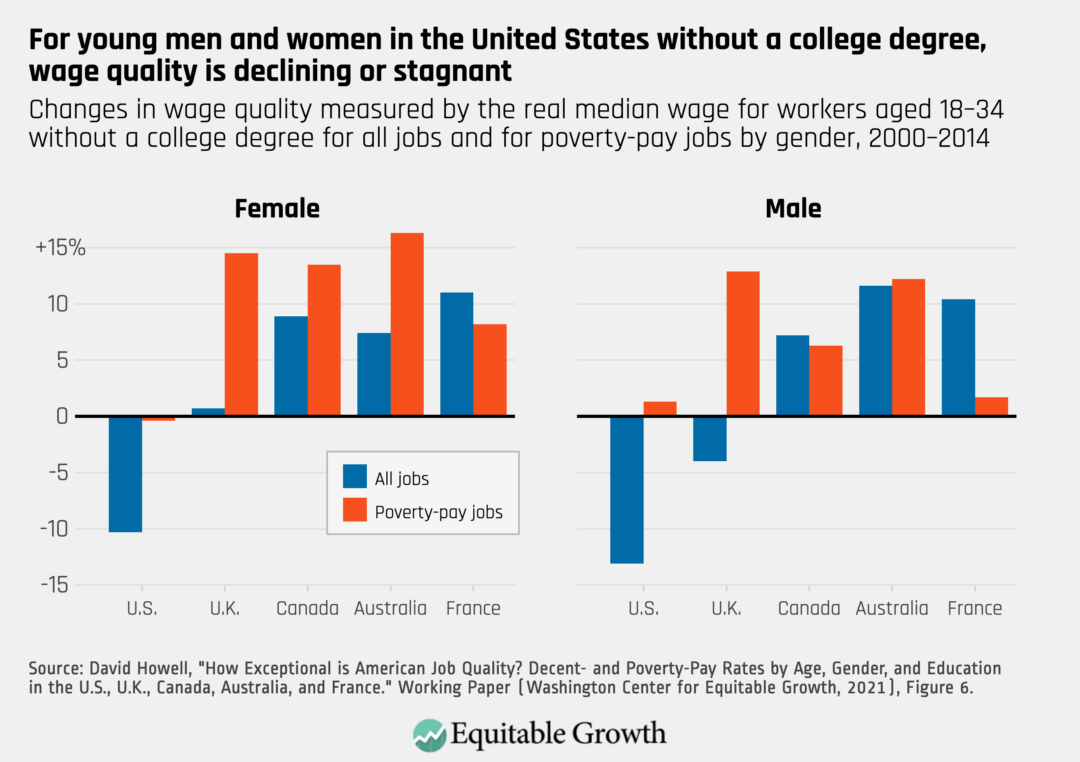

Indeed, earnings for young workers without college degrees are not only much better in other countries, but wage quality for these workers also has actually improved in many other countries in recent years. For instance, between 2000 and 2014—a time of growing use of technology and other global economic changes—real median wages for young men without a college degree in Australia grew by 11.6 percent. In the United States and the United Kingdom, by contrast, wage quality for young workers without a college degree stagnated or declined during this period. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

While these patterns of declining pay quality in the United States are most striking for young workers with lower levels of education, Howell has previously shown that pay quality is also declining for young workers with degrees. His 2019 working paper showed that between 1979 and 2017, the share of young workers with less than a college degree holding poverty-pay jobs (defined in this paper as “lousy-wage” jobs) rose from 35.8 percent to 56.5 percent.

Yet Howell also demonstrates that the share of young workers with a college degree in poverty-pay jobs rose as well, from 10.8 percent to 14.7 percent. This analysis further challenges narratives of skill-based job polarization because, as Howell notes, the share of young workers with a college degree in jobs at the top and middle of the job-quality distribution declined between 1979 and 2017, while increasing in the bottom of the distribution.

The close connection between worker power and pay quality

Howell’s second new working paper, “Low Pay in Rich Countries: Institutions, Bargaining Power, and Earnings Inequality in the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia, and France,” builds on the cross-country earnings-quality analysis to explore potential reasons for the countries’ different pay-quality patterns.

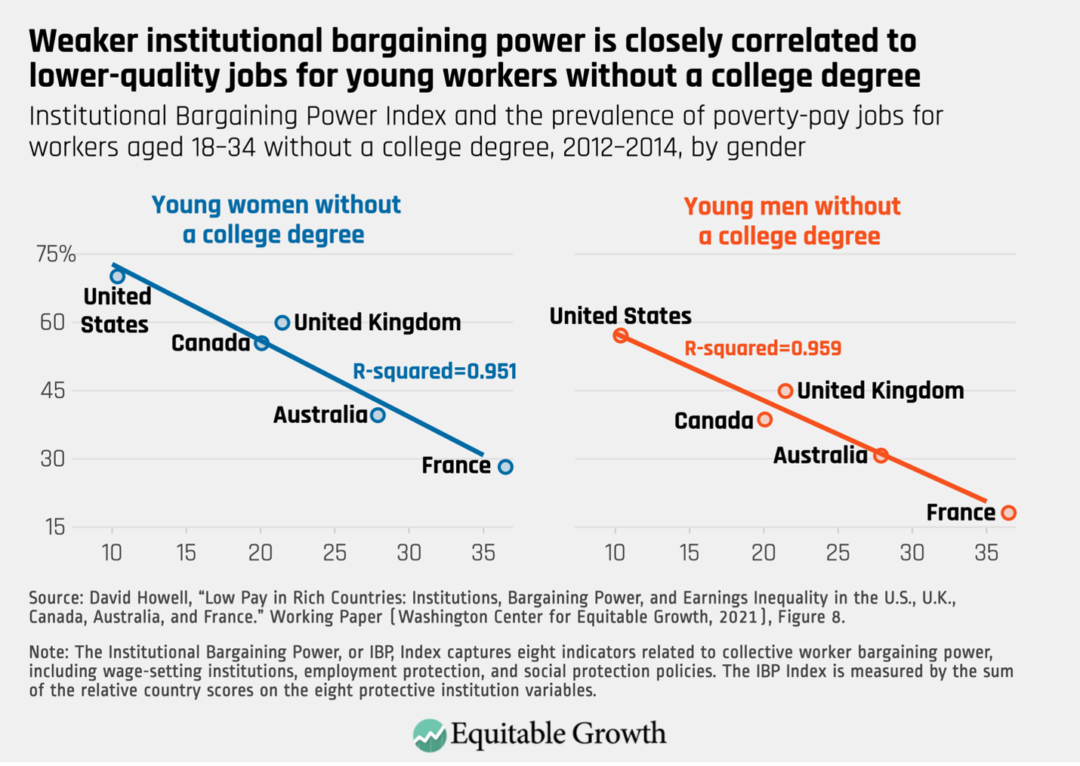

In order to measure the relative strength of labor institutions and policies related to worker power, the author develops an index of institutional bargaining power that represents the types of national institutional and policy regimes that can affect workers’ bargaining power over pay—collective bargaining coverage, national minimum wages, employment protections, and income supports. The measures that make up this index each reflect the relative strength of each institution or policy between countries.

The United States ranks last in institutional bargaining power, compared to other similar economies—not only within the set of five comparable countries that are the focus of this analysis, but also in a broader set of 21 OECD countries. Within the five countries of focus for this analysis, France has the highest institutional bargaining power index score, followed by Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

The paper’s Institutional Bargaining Power Index captures a range of factors that contribute to worker power, which Howell considers through two broad channels. The first is wage-setting institutions, which include collective bargaining coverage, union density, centralization of bargaining power, and national minimum wage in relation to the median wage. These institutions can directly raise wages and strengthen workers’ ability to bargain.

The second channel is labor and income policies that include employment protections, unemployment benefits, other public income supports, and a country’s spending on training and job search. These policies strengthen workers’ bargaining power through improving their outside options and reducing their risk in the case of job loss, as well as improving job-match quality.

Howell finds that the differences in earnings inequality between the United States and the other countries for workers in the bottom half of the pay distribution—including young workers without a college degree—are almost entirely explained by countries’ policy decisions around wage setting and labor protections. Countries with protective labor policies and institutions that strengthen worker power have less inequality and higher pay quality for young workers in the bottom half of the wage distribution who do not have college degrees. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

This relationship between bargaining power and pay quality holds when Howell extends the analysis to a broader set of 21 wealthier member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Howell also finds consistent correlations between bargaining power and other measures of wage levels and distribution, such as the OECD’s 50-10 earnings ratio definition of earnings inequality and low-pay rate.

Conclusion

This research provides further evidence why a college degree or greater credentials is not the solution to U.S. pay inequality. Pay quality is indeed dramatically higher for U.S. workers with college degrees, but the evidence shows that the earnings differentials from education levels are not necessarily driven by changing skill requirements.

Instead, as Howell writes, the growing pay inequality in the United States and the differences between the U.S. economy and similar economies “reflect fundamental features of national institutional and policy regimes designed to regulate labor markets and protect worker interests.”

U.S. workers with college degrees have access to higher-paying jobs. But research increasingly shows that the growing wage and earnings inequality by education level in the United States is tied to decades of policy choices driving the rise of employer monopsony alongside the decline of worker power. Addressing the uncompetitive wage-setting practices by U.S. employers requires an interconnected suite of interventions, including raising the minimum wage, strengthening workers’ bargaining power, and bolstering labor standards enforcement through the pandemic and beyond.